Reflections on Teaching the Holocaust

Stephanie Kessler, English and history teacher at Collège Reine-Marie in Montreal

If you are thinking about bringing Holocaust education into your (in-person or virtual) classroom but feel intimidated by the subject, you are not alone. Teaching about this complex historical event poses challenges for even the most experienced teachers. In this blog post, the Holocaust Survivor Memoirs Program manager of education initiatives, Marc-Olivier Cloutier, asks Stephanie Kessler, an English and history teacher at Collège Reine-Marie in Montreal, about her experiences teaching the Holocaust. Kessler brings Holocaust education into the curriculum year after year, using many of the Holocaust Survivor Memoirs Program resources. Here she shares her advice and reflections on teaching about the Holocaust, as well as the impact her teaching has on her and her students.

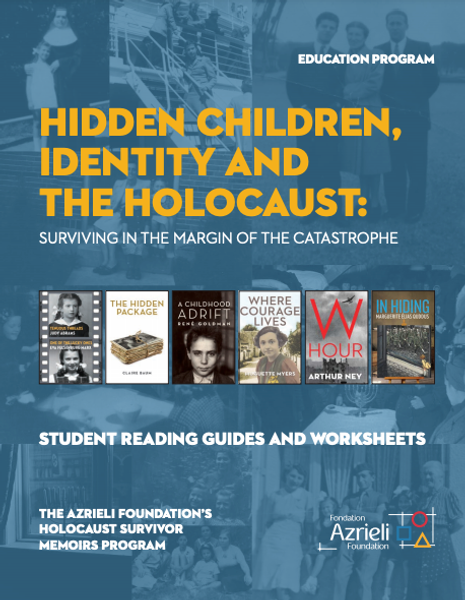

The cover of Hidden Children, Identity and the Holocaust: Surviving in the Margin of the Catastrophe

What advice do you have for teachers who are thinking about integrating Holocaust education into their classrooms?

Unfortunately, our history curriculum in Quebec does not have a detailed unit on the Holocaust and very briefly glosses over World War II. Also, I believe many teachers find the topic difficult to take on and are often afraid that their own lack of knowledge is more of a hindrance than anything. I would reassure them by saying it is not as hard, or as daunting, as they may think. There is no shortage of information that is readily available for them to use, from the Azrieli Foundation’s Holocaust Survivor Memoirs Program to all the museums that offer incredible teacher resources (primarily the Montreal Holocaust Museum and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum). There are many ways this topic can be addressed, whether with elementary school children or older high school students. Using literature is great, but students do need some context. For example, before teaching a fictional story, I will show short videos that provide historical context, or have students work on the Hidden Children educational resource provided by the Azrieli Foundation’s Holocaust Survivor Memoirs Program. I have also used many of the program’s memoirs as research material and for extended reading activities. Then we will attend a lecture with a survivor to wrap everything up. When we meet a survivor, studying the Holocaust jumps from being a historical event to something more tangible. When we meet a survivor, it becomes real, not some obscure event in the past. Real people suffered; real people survived. And my students often learn empathy from the meetings. It is very obvious that the students get so much out of this unit as a whole, and I am sure a lot of teachers do also, including myself.

What place do you feel Holocaust education has in your classroom, and what motivates you to keep teaching this topic?

The Holocaust marked the twentieth century with one of the deadliest genocide in modern history. Teaching this history is also an opening to discuss other genocides, as well as current events. As a certified history and English teacher, I believe that context is important. It would therefore be impossible for me to present stories with themes of racism and genocide without making sure my students understood the context in which they were written. For example, it would be difficult to talk about the history of colonialism without bringing in genocide. And so, in teaching critical thinking in the context of social justice education, a unit about the Holocaust is an important part of my curriculum. Many injustices faced by people in modern history have similar starting points, and there are warning signs to watch out for. All genocides have gone through particular steps that we all need to take seriously. We would also be doing a disservice to Canadian history if we did not talk about our own past policies, which included slavery and antisemitic laws.

Is there a moment that stands out for you from your years of teaching about the Holocaust? What about it has left an impact on you?

I would not say that there is one moment in particular, but rather each year when my students engage in a deeper understanding of what went on during the Holocaust, they are always taken aback by the sheer horror and magnitude of it. This awareness is further compounded when they learn about a survivor and attend a lecture by a survivor. I can always see an actual transformation in them; the Holocaust is no longer an obscure moment in history, but rather a concrete event that brutally affected millions of people, real people who could have been our friends, neighbours and even teachers. It is these reactions that motivate me to not only continue to teach about the Holocaust, but also to increase my own knowledge, not only about the events surrounding it, but also about how to teach it respectfully and with integrity.

How has the current state of the world affected your teaching and, in particular, the ways you think about and approach teaching about the Holocaust?

Sadly, what has been going on over the past few years, with the rise of extremism around the world, has provided me with a lot of teaching opportunities to bring the subject closer to my students. We often say that we teach history in order for it to not repeat itself, but in reality, we seem doomed to continue making the same mistakes. The rise of antisemitism and Islamophobia and the continuing gaps in racial equality have allowed me to make connections between much of the propaganda from Nazi Germany and the rhetoric we hear today. When my students learn about the stages of genocide and the steps taken by the Nazis at the beginning of the Holocaust, they can see how volatile democracy is. It is important for students to feel connected to what they learn, as well as invested in their learning; authentic and real-world instruction is key. The rise of extremism now further brings forward the question of the role of observers, witnesses, bystanders, victims and perpetrators. A question continues to resonate: How can we change direction and prevent another genocide? My students often come to the conclusion, on their own, that this could happen in our own society if we are not careful.

For more guidance on how to teach about the Holocaust, see our new guide: The First Step: A Guide for Educators Preparing to Teach about the Holocaust. And for more educational resources and guidance to support your teaching of the Holocaust, visit https://memoirs.azrielifoundation.org/education/.