Martha Sorger

Born: Košice, Czechoslovakia (now Slovakia), 1928

Wartime experience: Ghetto and camps

Writing partner: Lauren Wintraub

Martha Sorger was born in Košice, Czechoslovakia (now Slovakia), in 1928. Before the war, Košice came under the control of Hungary. After Germany invaded Hungary in March 1944, Martha and her family were confined in a ghetto and a brick factory.

In June, they were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where most of her family members were murdered. Martha and her sister Valerie were selected for work. They were first deported to several forced labour camps in Latvia — in Riga, Libau (Liepāja) and Dondagen (Dundaga). In the following months, Martha and her sister were in the Stutthof concentration camp and the Glöwen and Ravensbrück camps. Martha and Valerie were liberated in May 1945. After the war, Martha returned to Hungary. She married in 1952 and two years later had a daughter, raising her in Budapest. After the 1956 Hungarian Uprising, her family fled Hungary for Austria and then immigrated to Santiago, Chile. There, Martha opened a Hungarian restaurant and later bought and ran a guest house. In 1961, Martha and her daughter were allowed into Canada, where her son was born. Martha and her husband eventually divorced. In Toronto, Martha worked as a bookkeeper. She met and married Joe Sorger, and they started a new life together. Martha Sorger passed away in 2025.

Where My Life Began

My story begins on February 11, 1928, in Košice, Czechoslovakia. I was the fourth child of Rella Gottlieb and Samuel Grossman. Three children were born before me — Eugene (Jenci), who was sixteen years older than me; Lenke, who was fourteen years older than me; and Valerie (Vali), who was four years older than me. My father was a very family-oriented man who would do anything for us, and I have only the fondest memories of him. My mother was a very intelligent, shy and fine woman. When my parents married, my father was a wealthy and successful businessman, but a bad deal with the army bankrupted him, and by the time I was born, their fortunes had changed for the worse. We were rather poor, but we had a very nice life.

Following World War I, when my parents lost their wealth, my father had to open a bodega. It was on Várkapu utca (street) and then moved to Harang utca. Because my mother was shy, every morning, my father would go to the market to buy all the food and goods the store needed. When my father returned, my mother would start preparing the food to be sold at lunchtime. Among the many goods sold at the bodega were large jars of sauerkraut and tomato sauce in bulk, made by my mother and enjoyed by both my family and the customers. My eldest brother and sister worked, and Valerie and I went to public school a little ways away from where we lived. We always felt like the life we lived in Košice was similar to what life would be like in Prague or Budapest in that it felt like we were living in a large, bustling city.

We lived in quarters behind the storefront. There were three bedrooms and a kitchen. One bedroom doubled as a room where meals were served. Although we had electricity for lighting, we did not have indoor plumbing, which made going to the washroom difficult, especially at night; I always had to ask one of my parents to come with me because I was afraid to be outside alone in the dark. Since the only heated room was the one in which meals were served — it had a wood-burning stove — I would often go to bed with a warm bottle of water or a heated brick at my feet to keep me warm throughout the night. My siblings and I spoke to each other in Slovak, but my parents spoke mostly in German and my siblings and I would answer them in Slovak or Hungarian.

Although we did not have much, we made do with what we had and helped whom we could. We had freedom, happiness and democracy, and life was truly good until the Hungarians took over in 1938.

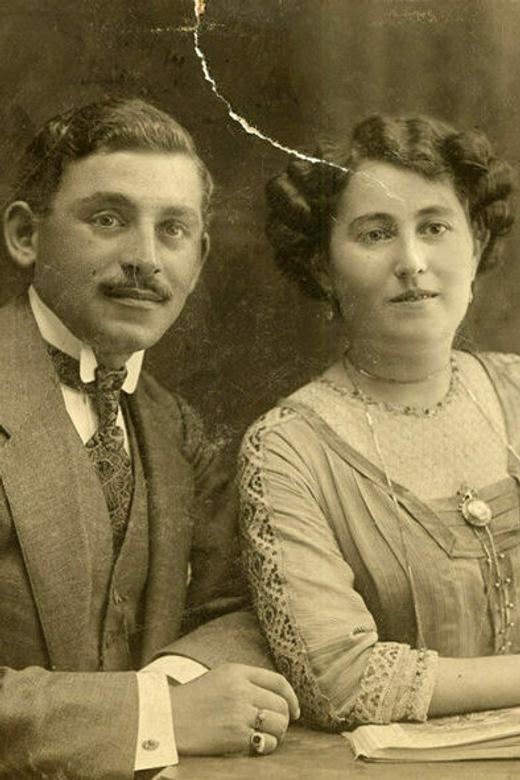

Martha’s parents, Samuel Grossman and Rella Gottlieb, on the occasion of their engagement. Eperjes, Hungary (now Prešov, Slovakia), 1911.

Martha Grossman in her school uniform. Kassa, Hungary (previously Košice, Czechoslovakia), 1939.

Hungary Invades

In 1938, when the Hungarians came to our country, everything changed. I was ten at the time, and the very first day the Hungarians arrived, our family (and the rest of the community for that matter) noticed a big difference between the Czechoslovak army and the invading army — Hungary’s was quite poorly dressed. The next day, we saw Miklós Horthy, the Hungarian head of state and the ruling regent of the Kingdom of Hungary, ride in on his white horse. The takeover seemed to me to have come out of nowhere, and it all happened very quickly. When the soldiers entered my neighbourhood, a predominantly Jewish one, they started commenting on how stinky our street was because of the number of Jewish people and stores it had. It was at this moment that our family first began to realize that our community had lost its freedom.

Shortly after Hungary took over, I felt the changes in my school and day-to-day life. I was in Grade 5, and although I had spoken Hungarian, it became mandatory for students to be able to read and write in Hungarian as well. One day, I was late getting back to school after eating lunch at home, as we all did. When I returned to school, another non-Jewish girl was arriving late as well. The other girl was not reprimanded or even questioned, but the teacher repeatedly smacked my palms with a ruler, just because I was Jewish. It was because of little things like that that I knew my life was changing for the worse.

Another time, I went to buy some stamps. As I was starting to cross the main street, a car quickly approached and I jumped back to avoid being hit. When I was safely back at the curb, a Hungarian policeman who had been watching me said, “What? Are you worried about your stinky Jewish life?” He had seen that I had been scared by the passing car. I felt miserable and helpless, and there was nothing I could do about it.

The Camps

During our time in the Košice ghetto in 1944, news came that two transports had left the brick factory for an unknown destination. We were advised to pack up because we were going to be transported back to the brick factory for deportation. The Jews of the ghetto were forced to walk back to the brick factory.

Two days after returning to the brick factory, a third transport left. My sister Lenke had been engaged to her fiancé, Nandor Jakubovicz, for a long time, but the wedding kept getting postponed because of our constantly worsening situation, which also meant Nandor was unable to work to support a family. Once back in the brick factory, with the future looking very uncertain, it seemed like it would be better for Lenke to be married than to be a single young woman. So Lenke and her fiancé were married at night in the brick factory under a chuppah in the middle of a horrible rainstorm. It was terrible to have to see my sister married in such a dreadful place in such an anguish-filled time.

A few days after the wedding, our family was put in a cattle car with others from the brick factory. We were enclosed for three days as we travelled to Poland as part of the fourth deportation. Within one car, there were about fifty people and some luggage. Everyone had a little bit of bread because the remaining members of the Jewish council had given everyone a loaf of bread as we were leaving the brick factory. During the latter part of our journey by train, my mother got quite sick. Right before we arrived at our destination, the train stopped for a couple of hours, and my father, optimist that he was, thought that the soldiers had changed their minds and that we would be taken back to Košice. Unfortunately, we had just been stalled by some sort of malfunction and we continued on to Auschwitz.

We arrived at Auschwitz on a morning at the beginning of June. When the soldiers opened the cattle-car door, we saw barbed wire. Behind the barbed wire, we saw men and women without hair, dressed in strange clothing and hats, and I thought that this must have been the crazy people’s Lager (camp). Once we got out of the train, the guards said that the men and women must separate so that we could take showers. Everyone was fighting and crying. That was the last time I saw my father. Lenke, Valerie, my mother and I lined up behind the other women as instructed by the soldiers. At the front of the line, there was an officer instructing women to go either right or left. Many sisters, daughters and mothers were clinging to each other crying, trying to avoid being separated, but my sisters and I were crying too hard to hold on to each other. The guards told Valerie and me to go right. Later, we saw that both my mother and Lenke had gone left. Other girls in the line told my sister and me that the guards had wanted Lenke to separate from my mother, but when the officer wasn’t checking, my sister ran after my mother, who had been sent to the opposite side. The Friedman girls from Košice said that I was lucky because my sister was with my mother, and I told them not to worry because Lenke would look after their mother too. At this point, everyone was still panicking and crying. That was the last time I saw my mother and Lenke.

Once the sorting ended, the group was led to wooden barracks. Girls who had been in the camp for a while were yelling, “Eat, eat what you can eat now!” I had a bottle of raspberry syrup that we had taken from the brick factory for my mother because she was not well. After hearing the girls yelling, I started sipping from that. Unfortunately, drinking the syrup had adverse effects, giving me diarrhea for a week. Once we were inside the barracks, officers told us to take off our clothes and put them in a bundle on the side of the room. We could see that the men were stripping outside. Then some of the men started to bring in the clothes that the others had left on the ground while changing outside. All the women in the barracks got flustered; some were crying because they did not want a man to see them naked. The men tried to calm some of the women down and said not to be concerned because they weren’t looking. One of the men happened to be Nandor Jakubovicz, Lenke’s new husband. He asked where Lenke was, and Valerie and I told him she had gone with our mother. When he heard that, he raised his hand and waved downward to indicate that all was lost. He had heard news from the outside and knew where my mother and Lenke were headed. He then said not to worry because our father was with him, that we should be strong and that after the war, we would all meet again in Košice. We never saw him again.

My sister and I were lucky because, about three days after we arrived, the guards came looking for workers to transport to another camp. My sister and I were relatively strong, so we went. I remember it was a rainy day when we were taken to the transport wagons and I was so thirsty because they hadn’t given us any food or water in the morning, and I still had bad diarrhea. Everyone was opening their mouths, trying to catch the rain just to get even a drop to drink, but it didn’t help me much. Then I saw a drop of water on each of my sister’s earlobes. I sucked the two little drops of water from them.

When we arrived at our next destination, we didn’t know that we were in a working Lager in Riga, Latvia. Here, everyone had their own clothes on, unlike me and the rest of the people who had exited the wagon. We were allowed to clean our clothing in a large circular washing basin in the middle of the camp. While we were washing up, the guards said that they could not give us anywhere to sleep; the Jews who were already there would have to accommodate us. A woman from Vienna approached my sister and me and told us to come and sleep on her top bunk. In the barracks, people were asking what was going on in Auschwitz because they didn’t understand why we were wearing stripes and had shaved heads. We told them what we had seen in Auschwitz and they were shocked.

Although there was not a lot of food there, I wouldn’t say that people were starving. For the rest of the time, we worked in a shipyard. Any working Lager was better than a Vernichtungslager, a death camp. My sister and I stayed at this camp for only a week. Then we were taken in open trucks to Kurben (which we called Kurbe), which was part of another labour camp in Latvia known as Dondangen.

The trucks stopped in a forest, and everybody in the wagon had to walk for approximately a day to reach the Lager while under the Latvian soldiers’ watch. When we got there, we saw that the barracks were not permanent structures but just circular tents. This was a Zeltlager, a tent camp, and each tent housed fifteen people. The soldiers told us to go and cut down small trees for covering the floors in the tents and to use as bedding. We used leaves to make our makeshift beds a little more comfortable, and we built a small fire pit in the middle of the tent.

During the days, it was very hot while we worked on building roads, and during the nights, it was very cold and almost as bright as during the day. We would collect wood to feed the fire so that we could keep warm at night. We would all sleep right up against each other for warmth, and in the middle of the night, we’d all turn over together. One person always had to get up part way through the night to feed the fire, and we all took turns doing this.

Since the Soviet front was moving in, many of us were relocated to the Libau Lager in Letland (Latvia). We had to make the journey on foot from Kurbe. When we got to Libau, we were held in a park or open area of some sort for two days and two nights. During the night, we saw shooting and fighting between the soldiers in our camp and the invading army. We were scared that we might be attacked or hurt. No one knew exactly what was going on.

It was May 1945 and we were finally free. Everyone was overjoyed and happily kissing each other, and still no one knew what to do.

The Journey Back

Ravensbrück was a terrible concentration camp, for women only, in Germany. We arrived at night and were taken by German soldiers to the bathhouse. Everybody was standing and waiting in the middle of the room, but my sister and I had drifted off to one side. We saw what looked like six to eight closed water basins, and I opened one and realized there was warm water in them. I told Valerie and asked her if she thought we should wash our hair and she said yes. My sister and I began to wash our hair, and when others saw what we were doing, about half of the group in the bathhouse pushed us away so that they could wash their hair. Most of the room was now covered in water and everyone had a terrible night because we were wet and cold. Although the water had ruined our night, it was good that my sister and I had washed our hair because the next day the guards checked everybody’s hair for lice. The half of the women who had not washed their hair did have lice and the guards shaved their heads. Those who did wash their hair had gotten rid of enough of their lice, so my sister and I got to keep our two inches of hair, something we were very proud of.

The next day, all of us who had been travelling together were sent to the barracks. It was terrible. The entire building was lice-infested, and everybody already living there was so weak that if you accidentally grazed them while walking by, they would fall over. They had no strength to walk and they peed in their beds. At this point, my sister and I again thought that this was the end for us.

On our second day there, the German guards told us that we were going to be taken to Sweden by the Red Cross. Valerie and I were registered and assigned to a group that was going to be transported on a certain bus. We saw that the Red Cross buses were coming and we were overjoyed. But before the buses could fully pull up an alarm went off; the buses turned around and went back into the forest. The women were led back into the empty, dirty barracks and everyone was devastated.

In the barracks, the German guards told us to remain in the groups we had been assigned to be transported in because they did not want to have to re-register us. We were kept in the same barracks the next day, and if anyone ever went to the latrine, we would tell them to hurry back in case the Red Cross suddenly showed up. The next day, the buses did come back but, frustratingly, they took the other group instead of us. So, the German guards instructed us to leave the barracks and to start walking. When we started to walk, we saw bloodied and wounded German soldiers coming off a train. They were calling out for water. Some of us wanted to climb up to the trains and bring them water, but others said, “Why? Do you think they would bring YOU water?”

When we walked even farther, many people in the group realized that we had passed through the same villages more than once. The group now understood that the SS soldiers who had been guarding us the whole time did not know where to take us. The soldiers had removed some identifying parts of their uniforms, and some girls were asking what they would do with us if the war was truly ending. The guards were no longer counting us as carefully as they had before, and so a few girls escaped into the forest. My sister and I were afraid to run away into the forest because we thought that if the war front reached us, we would be worse off in the hands of the Soviet soldiers.

At night, we were taken to a barn surrounded by an open field. Throughout the night, there was gunfire; the night sky was lit up. We tried to sleep but it was impossible, and when morning came, everyone was wondering why the guards didn’t come to wake us up. One girl went to find the officers, but they had left. Everyone started to cry because we didn’t know where to go. We found some potatoes around the barn, and someone made a fire to prepare them. We hadn’t eaten a warm solid meal in months. Later that day, a truck drove by, people hanging out of it, waving white flags, yelling that the war was over. It was May 1945 and we were finally free. Everyone was overjoyed and happily kissing each other, and still no one knew what to do. The group of girls, including Valerie and I, started to walk toward a town called Prenzlau, and when we arrived, we asked the first people we saw where we should go, but nothing had been organized for us.

My sister and I and a few other girls started to navigate the town but only on side streets, and I thank God for that. After the war, the whole country was in turmoil, and soldiers from the Soviet Union entered the town’s main streets, where they raped as many women as they could. Since my group travelled only on side streets, we were lucky enough to escape these men. We came to a house where a German family lived, and they let us in. They gave us food and told us that we could sleep on some straw in the storage pantry just below the ceiling of their barn. At night, we heard a door open to the house followed by desperate screaming. Following this, we heard the barn door open, but by this point we had covered ourselves in straw and were absolutely quiet because we were terrified of whoever had broken into the house. The next morning, the German family told us that the Soviet soldiers were going house to house, taking peoples’ money, jewellery and food, and that one girl in the house had been raped. We were very thankful because the soldiers had asked the family if anyone was in the barn and they had said no. That day, we left the German family and continued to navigate through cities and villages using side streets.

At one point on our journey, we saw a number of telephone poles connected by wires, leading to some sort of warehouse. We followed the wires to the warehouse and found a truck filled with American soldiers who were travelling through villages and cities and stringing phone wires. We asked them if we — there were maybe five of us — could hitch a ride in the back of their truck. The Americans said yes, and so during the day, we travelled with them, and at night, we stayed in strangers’ houses. A few days later, the truck reached its destination in Germany, and we realized we were no longer really welcome because the soldiers wanted to have a good time with the German girls in town. The Americans suggested a town we could go to in order to meet up with others from Czechoslovakia.

We went to that town, and we met up with a group of Jewish Czechs. While waiting for the transports to take us home, the Czech group stayed together. We relied on the men to watch over the girls and stop any Soviet soldiers from raping them. They were not always successful, but fortunately Valerie and I kept out of harm’s way and made sure not to attract attention. After a short while, buses came and took both the men and women to Prague.

In Prague, our group was greeted like war heroes. Valerie and I thought it was strange to think of concentration camp victims as heroes and we sadly joked with each other privately that it was indeed heroic for young women to make it through the war as virgins and that we could congratulate ourselves.

Martha and Joe Sorger on the occasion of Joe’s sixty-fifth birthday. Joe is holding a Sefer Torah, a surprise gift from Martha, to be housed at Beth Jacob Synagogue. Toronto, 1987.

Martha (back row, third from left) with her sister and members of her mother’s family after the war. In back, left to right: Martha’s cousin Tibor; her sister Valerie; Martha; and her cousin George. In front, Martha’s uncle Lajos and her aunt Aranka. Debrecen, Hungary, circa 1947.

Martha and her daughter, Susan, after arriving in Canada. Montreal, 1961.