Helen Verblunsky Yermus

Born: Kovno (Kaunas), Lithuania, 1932

Wartime experience: Ghettos and camps

Writing partner: Bev Birkan

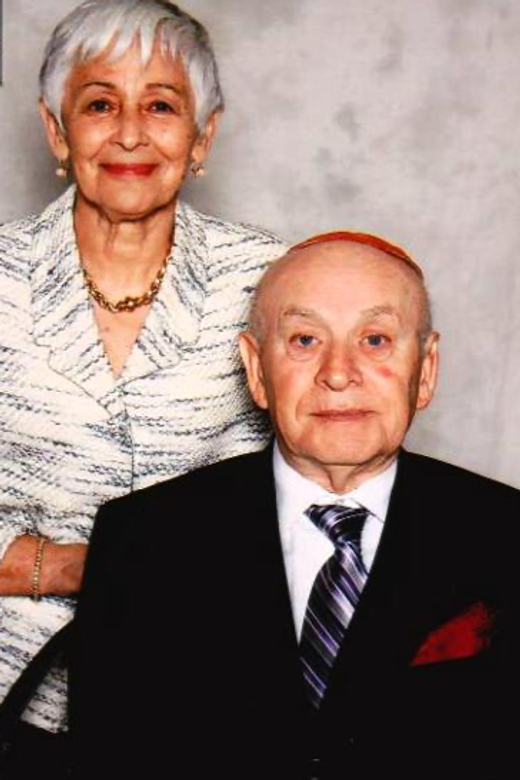

Helen Verblunsky Yermus was born in Kovno (Kaunas), Lithuania, in 1932. She survived the Kovno ghetto, the Stutthof concentration camp and forced labour in the subcamps of Bromberg-Ost and Elbing.

Helen and her mother were liberated by the Soviet army in January 1945. They lived in Poland and in displaced persons camps in Austria before immigrating to Canada in 1948, where they settled in Montreal. Helen studied at Montreal’s United Jewish Teachers Seminary of Canada and then worked in a factory. She married Aaron Yermus in 1952 and together they raised a family in Toronto. Helen has been a Holocaust educator since 1985, speaking to students through the Toronto Holocaust Museum. In 2019, her story was featured in the documentary Cheating Hitler: Surviving the Holocaust.

We were not allowed to have any books. The Germans had ordered all books to be turned in, and then they burned them. But I was never without a book. I resisted by reading.

The Kovno Ghetto

Each time people were taken away, the ghetto shrank. Families were relocated. People who survived the Big Action took over the houses where those who had been killed had lived, and I eventually met new friends.

My father was still working for the Gestapo. My mother was taken to the military airport in the Aleksotas suburb, where the Germans were enlarging the airport by using Jewish slave labour. My mother was a gutsy woman. She would wear a fatsheyle, a very large kerchief, with a tartan plaid design that covered the yellow stars on the front and back of her clothes. She would take out something of value to hide in it so that she could exchange the item with a non-Jew for food. We were supposed to have turned over all our valuables to the Nazis, and they often searched people to try to find anything that was hidden or smuggled in. But people took chances. After making a trade, my mother had to smuggle the item of food back into the ghetto. Every day, as the labourers returned to the ghetto, the guards did sporadic searches. My mother risked her life on a regular basis. She was lucky. She returned with necessary items. My father would never have done that kind of thing; they were very different that way.

Life went on. My parents went out to work and I remained home with my little brother. Sometimes, my mother brought home flour and I would make dough with the flour and water and then cut it up to make noodles. For a while, we still had our Primus stove that was heated with kerosene. Then, one day, we didn’t have it anymore.

Because my father once kept a diary, I was inspired to do the same, and I had started to write in my diary from the day the Germans began their invasion. I wrote many things in that diary, but I don’t know what happened to it. We were not allowed to have any books. The Germans had ordered all books to be turned in, and then they burned them. But I was never without a book. I resisted by reading. I don’t know how I got them, but I did. I read books that were beyond my years, books that I would never have allowed my children to read. The books were Yiddish translations of Guy de Maupassant, Flaubert, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and Gorki. I also read books about Jewish history. I would find one and, when I finished it, find another. I read a book about Zionism by a British author. We were not allowed to have anything educational, but there were underground schools in the ghetto. And there was a secret orchestra. There was Jewish culture even though there wasn’t supposed to be any.

I remember singing songs to my brother. The two of us were always together. He was such a bright little boy. When he was three years old, while we were living in the ghetto, he told me the Soviets would be our Moshiach, Messiah. He was always listening. He would say, “Die Russen veldt kumen….” (When the Russians will come….) But we were far away from the Allied forces.

We lived in our house until the winter of 1943–1944. I was required to work a little bit in the ghetto. But I also had to look after my brother. I wasn’t forced to work. Sometimes I worked to get a piece of bread or something else.

From day to day, we never knew what would happen. The Germans grabbed people every day. Some people were “relocated” to Estonia. Some were put in detention in our previous neighbourhood synagogue. With all the people who were taken away, the ghetto continued to shrink.

That winter, we were ordered to move. The Germans were condensing the ghetto again and changing its status from a ghetto to a concentration camp. We were obliged to find our own living quarters. There were no newspapers, no ads and no way to find out where there was available space. There were no vehicles to help us move furniture. We had to find our own place to live. My mother had a friend who knew a man who was part of the Jewish police force of the ghetto. This police officer knew of a place that was in one of the three unfinished buildings that the Soviets had previously built for their workers. Through the intervention and help of this ghetto policeman, we were able to share a room with another family in one of those buildings. From what I can remember, they did not have young children like my brother and me. They would go out to work during the day.

The ghetto gate that had been close to where we had originally lived was no longer accessible and now we used the gate near Demokratu Square. Germans and Lithuanian and Ukrainian collaborators continued to grab, detain and arrest Jews at will. When my parents went to work in the morning, we never knew if they were going to return safely at night. They, too, never knew if they would find my brother and me when they returned.

News travelled fast in the ghetto. Someone, somewhere, had access to a radio or a newspaper. I had heard the names Roosevelt and Churchill. We knew that the Soviets were beating the pants off the Germans, pushing them into a retreat. But in spite of their military losses and defeats, they continued their war against the Jews.

Suddenly, terrible news spread through the ghetto that the children were going to be taken away. Everything happened so fast and there was barely time to react. I saw my mother move one of the sofas. She pulled it away from the wall and placed some blankets and pillows to make it look like the sofa was extended. Beneath the blanket, she hid my brother.

I stood in the middle of the room, visible. My mother didn’t move and neither did I. I saw where she had hidden my brother, but what about me? We couldn’t face each other. I felt like I could barely see.

To enter our room, there was a very little hallway. There was one entry to go from the right and one to go from the left. When the door moved, it created a little corner. Suddenly, an idea popped into my head and I rushed to hide myself in that tiny space.

We lived several floors up. We heard feet running up the stairs, female voices crying, children crying. It was bedlam. Terrible things were happening. “Raus! Raus!” (Out! Out!) the booming male voices of soldiers yelled. I stood still, frightened. It didn’t take long before two soldiers rushed into our room. I could see them through the crack in the door. They didn’t move the sofa. They didn’t peek behind the door. They ran in and they ran out, just like that. We were safe. So far.

My father returned home. He had heard about the Kinderaktion, the Children’s Action, and he didn’t know whether he would find us there. There were a number of children who had not been taken. Our parents still believed that there was a threat, so they took us down to the main floor of the building where there was a trap door. We were told to crawl in and then they closed the door. There was very little space. I held my brother close. Mothers with children held them close. The children knew not to make a sound.

We later learned that the following morning, the Germans took a large number of the Jewish ghetto police force to the Ninth Fort, threatening to kill them and their families if they did not reveal where the children were being hidden. At least thirty-six policemen were shot and killed.

Soon, we heard noises. The trap door opened. “Raus! Raus!” The Germans had found our hiding place. Nobody made a sound. We didn’t have to be told to be quiet. We got out. They herded us outside the building. The area was an unfinished field with mud and snow. Trucks surrounded us. Soldiers with guns surrounded us. Dogs were barking. We were treated like criminals. We were told to get onto the trucks. I stood with my brother. He was right in front of me, and I held him tightly in my arms. We stood, together like that, and the soldiers demanded I let him go. I didn’t know what to do. I was frozen, holding my brother to keep him safe. All of a sudden, there was a dog on top of me. It bit down on my right wrist, which started to bleed. For a fraction of a second I was startled and temporarily let go of my brother. The SS grabbed him from my arms and sent him to the truck. I watched, in shock, as he looked back to see if I was following. I wasn’t told to go — I wasn’t following.

This was the Kinderaktion of March 27 and 28, 1944. I don’t know how I returned to our room alone. I was in a daze. Horrified by what had happened to my little brother. My mother had been upstairs and had not known what was happening. We were devastated. Now we were three.

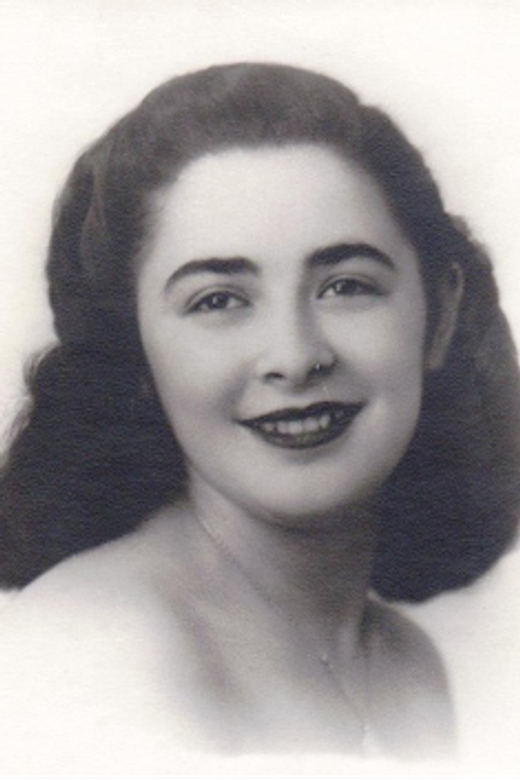

Helen with her father, Yitzhak, and her mother, Toba Leah. Kovno (Kaunas), Lithuania, 1933.

Helen in the Kovno ghetto. Date unknown.

Stutthof

We had been taken to the concentration camp known as Stutthof. We were kept overnight in the perimeter of the camp. It was huge. It was surrounded by thick electrified barbed wire. There were watchtowers spaced at different points with armed guards looking down on us. Perhaps the electrified fence was not enough to confine us. They needed the guards to watch us to make sure we wouldn’t escape.

There were thousands of people there. Kovno Jews were not the only deportees at this camp. Hungarian Jews had also been deported and “resettled,” and many were with us.

We were taken group by group into a very large hall. The guards were dressed in black SS uniforms. There were tables around the room and we were ordered to undress completely. Then we were examined by guards. Some women were given internal examinations. Group by group, we left our belongings on the floor or wherever we were told to put them. We were then told we were going to the showers.

Somehow, we had heard about gas chambers. We knew what they were and how they were referred to by the euphemism “showers.” We were sure we were going to die. There was a door from the large room into an even larger shower room. Pipes ran along the ceiling of the room, and many shower heads hung down from the pipes, spaced apart. This is so vivid in my mind. I can’t remember certain details, like if we had soap, but other details are very clear.

My mother and I held each other and waited. More and more people were brought into the shower room. Then the showers started and water came out. What a relief. On the other side of the shower room, there was a door through which we exited. We walked out naked. There were no towels. We were handed uniforms — striped pyjama tops and bottoms — with bands of red with a number and a yellow star on the front and a yellow star on the back.

We were led to barracks, where there were rows of bunks with narrow spaces between each row. We went into the bunks, which had room for ten across on a board. If you ended up in the middle you had to crawl over people to get out.

Each day, we were counted twice. We were also given a small portion of bread with a little pat of margarine.

We never had another shower since that first one when we arrived in July. In September, we were ordered to work. Our striped uniforms were taken away and we had to find our own suitable clothing and shoes. My mother found something that looked like a coat, rope that she could use to hold it together and a pair of shoes. The shoes were huge, maybe size fifteen. One could fit both feet into one shoe. The shoes had wooden soles and canvas tops like clogs. I think my mother used part of the rope to tie the shoes to her feet. I didn’t have any shoes.

We were sent out of the camp on trucks and then on trains. We arrived at a smaller camp that was set up with tents. There were fifteen hundred of us. This place was called Bromberg. It didn’t have any killing facilities: no gas chambers. We slept on straw bedding, in the same clothes, every day. We could never wash, clean or change our clothes or bedding. We were there for a couple of months. The weather in September was not too bad, but it soon became inclement. Autumn can be bitter with cold, wind and rain.

Our job was to dig trenches, wide trenches for German military vehicles and narrow ones for soldiers on patrol. Every day, we marched out with our picks, shovels and spades, the tools of our trade, to our destination. We got very little rest. We could pause only briefly to eat the portion of bread we had been given before we left the camp.

From time to time, there were horrific incidents. There were some young Hungarian women who were pregnant. One gave birth when we were working. The babies never saw the light of day. One minute they were born, the next they were gone.

One day, when we were marching back to the camp, we saw pigs eating from a trough on one of the nearby farms. All of us attacked the pigs to get them away from the trough so we could eat what they were eating. We were starving. Even though the guards had guns, we tried to get some food. The guards rounded us up to continue our march back to camp.

Losing Hope

In the middle to end of November, our job was finished, and we were taken to a different place called Elbing. We were again assigned to tents, and then informed that they wanted five hundred volunteers to go back to Stutthof. We weren’t forced; it was simply requested that we line up.

I was still without shoes. The ropes on my mother’s shoes were frayed and there was not much left of them. My whole body had broken out into sores, except for my face. Lice constantly crawled all over us. Up until this time, we always felt there was a shred of hope that liberation was near, that we would be able to survive someway, somehow. My mother and I always stayed together.

I couldn’t remember ever feeling the desperation that we were feeling then. In the three years in the ghetto, even during the worst times, there was a glimmer of hope. Even the ghetto archives had been hidden with the hope that they would tell the history of what had happened. And even after my brother was taken from my arms, I still had some hope.

Now, both my mother and I began to feel there was nothing to look forward to. My mother and I tried to put our situation into perspective. I was beyond my years, as my brother had been when he said, “Die Russen veldt kumen…mir zein frei.” (The Russians will come…and free us.) This was the bleakest time. We had nothing. We would go back to Stutthof, and what would be, would be.

We lined up, five in a row, which was how we were always counted. We were the first in line, standing behind a table. We weren’t the only ones who lined up. There were many, many people behind us. Instead of starting at the beginning where we were, the officers took the last ones first. They had played a trick on us. The fickle finger of fate.... They counted the five hundred and the rest, including us, went back to their tents.

What happened to those five hundred, I have no idea.

We started back at the same routine, using picks, shovels and spades and going out to dig. The guards often beat us. We had to keep working, lifting heavy shovelfuls of dirt. We had to do it in a specified manner. We really were slave labourers. My toes were festering. Snow was falling. We had the same garbage clothing filled with lice and the same lice-filled straw. We continued to be counted.

This went on until January 19, 1945. That day, we were lined up to go to work when we heard an announcement that we were not going to go to work that day. The camp was being evacuated. The internees were going on an evacuation march — in reality, a death march.

We lined up to go. No one stayed behind willingly except for people unable to walk, people in poor health or people staying with a sick relative. Family, of course, mattered. These people were in a sick room. Reva, a young girl my age, was very ill, and her mother would not leave her behind. She stayed. There weren’t any doctors, nurses or medication. These people were left behind to die slowly. Many couldn’t function anymore.

My mother saw guards swarming all over and asked the guard nearest us if she and I could go back to our tent to get some straw to help keep us warm. We quickly went to get the straw and returned to the guard to whom my mother had spoken. The guard raised his gun and said that because we had left, we now had to stay behind. When a gun is pointing at you, even if you know you are going to die, you obey the gun. We were forced to stay behind. The others marched off. I never again saw any of those people who I had known.

In our camp, there was a round hut made out of veneer boards with a roof. A chimney went through the little roof. The hut was for the guards to get a coffee or to warm up when they were on duty. We saw smoke coming out of the chimney. We were ordered to enter this hut along with the others who had remained behind. We were ordered to lie down on the ground. There was no straw in the room because usually, no one slept there. We lay down in a circular pattern in the round room. Three guards came in. One of them had a very large syringe that looked big enough for a horse. He went around from one person to the next, injecting each of us with something. We stayed lying down on the ground like that for one night, then two, then three. I think some people may have moved, but I don’t really recall. I didn’t move. My mother didn’t move. The people close to me didn’t. The guards did not come to look in on us. No one came, even though the area was not deserted; it was surrounded by homes and farms, and people lived nearby.

Then, on January 24, 1945, a Soviet scouting group discovered us. They told us the date. We had been immobile, without food or water, from the 19th to the 24th of January. I wonder, now, how this was possible.

The Soviets told us that we were free, that there was no one guarding us. The German guards had disappeared. This was our liberation.