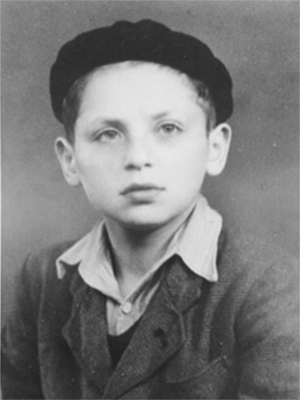

Andrew Tylman

Born: Sochaczew, Poland, 1933

Wartime experience: Ghetto and hiding

Writing partner: Sylvia Solomon

Andrew Tylman was born in Sochaczew, Poland, in 1933. When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Andrew and his family immediately fled their small town for the city of Warsaw.

After the Siege of Warsaw, they went to the town of Łowicz, where they lived until early 1940. When conditions under the Germans worsened, they made their way back to Warsaw. Andrew and his parents were living in the part of the city that became the ghetto in the fall of 1940. Through a series of arrangements, Andrew’s father was able to keep his family out of the selections and deportations that began in 1942. Just before the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in spring 1943, Andrew was hidden with Polish people outside the ghetto who had been paid by his father. His father also managed to escape the ghetto shortly before it was liquidated and eventually joined him in hiding. Andrew’s mother died while trying to escape the ghetto. Andrew and his father hid in a variety of places from spring 1943 until the Soviet liberation of Poland. After returning to their hometown, they moved to Lodz, wary of the continuing antisemitism and pogroms in smaller towns. Andrew eventually left Poland for France and then came to Canada in 1951. In Toronto, he ran successful businesses in the textile industry. Andrew Tylman lives in Toronto.

The War Changed Everything

I was born in November 1933. My earliest memory is the summer of 1937. We went on a summer holiday to Głowno, a Polish resort area. I went with my mother; she and I were there the whole summer and Father joined us for a week or two at a time. In those days, middle-class Jewish families didn’t go away in the summer for just a week or two; we went for at least a month and usually for two months, the whole summer. When we went away, we took kitchen utensils and comforters and towels and whatever we’d need for the summer. It is a lovely first memory to have.

Sochaczew had approximately 11,000 people, with almost 4,000 of them Jews. When I say we were well-off, it wasn’t palatial living. It was well-off for Polish Jews. We had two bedrooms, a living room, a very large kitchen, and a dining room off the kitchen. Our kitchen and dining room faced the courtyard; the bedrooms and living room faced the street. There was no toilet in our apartment; we either used chamber pots or went downstairs to the communal latrines in the courtyard. There was no running water. In town there were professional water carriers, called wasertreger in Yiddish; they carried a thick wooden rod across the shoulders behind the neck. Spaced on the rod were hooks on which they hung pails of water. Very strong people could carry six pails, but usually they carried four. The well was in the square across the street from us, so the carriers didn’t have to carry water very far to come to our apartment.

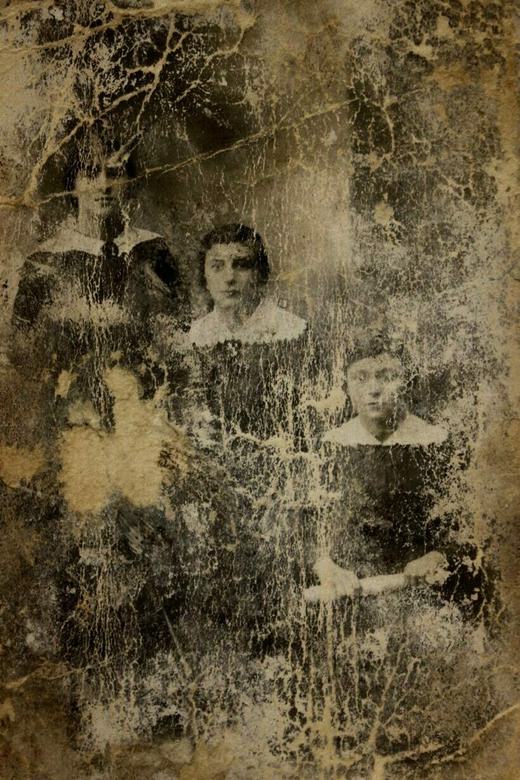

My mother was very protective of me. When we went to a barber, she’d bring a towel from home so I wouldn’t get lice or anything. Lice infestation was not a big problem in town, but Mother was very careful. We had a maid, a young Polish woman, which was not unusual for middle-class people. I taught myself to read, kid stuff. My closest friend was a cousin, my mother’s sister Dora’s daughter, Greta, from Łowicz, a somewhat larger town than Sochaczew. Łowicz was only about twenty-five kilometres away, so we got together often. Greta’s birthday was in April, so she was about seven months older than I was. I was too young to start school, but Greta was supposed to start Grade 1 in the fall of 1939. The war changed everything.

When the Germans Came

In September 1939, when the war broke out, we rented a horse-drawn wagon and packed our possessions. We couldn’t take furniture but we took all our valuables and as much non-perishable food as we could. I took a few toys and books. We rode to Warsaw, some seventy kilometres away. I remember being on the road with a few relatives. The road was busy with people riding or walking toward Warsaw. German planes flew overhead, strafing the road or dropping bombs. We hid in a ditch by the side of the road whenever we heard a plane approaching. The trip took the better part of the day. Mother’s brother lived in a large apartment in Warsaw on Leszno Street.

Most of the time during the siege of Warsaw we stayed and slept in the air-raid shelter in the basement. Almost everyone from the building was there. Bombs were falling. It was scary! When my father, mother and I went out on the street after Warsaw surrendered, we saw much damage — not many buildings were totally destroyed, but there were big gaps in them and a mess on the streets. Warsaw had been surrounded and then surrendered to the Germans on September 28, 1939. Now we were under the Germans.

After the Germans occupied Warsaw, we left the city and rode with several unrelated people in a horse-drawn wagon. We arrived back in Sochaczew late in the afternoon and went to our building. A nice gentile woman lived there; she had a store on the main floor. When she saw us, she said quietly, “Mr. Tylman, maybe you’d better not go up to your apartment. They were looking for you because you are one of those prominent Jews.”

When my father heard this he left immediately. He walked overnight to his in-laws in Łowicz. The next morning, Mother arranged to go to Łowicz with me. We stayed there with my maternal grandfather, Abram Grunberg, and the family. He was quite well off. He lived on Zduńska Street — number 27, I think — in a building next door to a large paint and hardware store that he owned and ran with his son. My aunt Dora lived there with her daughter, my cousin Greta, who, as I mentioned, was my best friend. Grandfather Abram was shorter than Grandmother Sara. I recall that he had to be careful with his diet because he had diabetes. On Saturday afternoons he enjoyed singing at home; he and a friend of his would sing cantorial tunes. The Łowicz synagogue was also on Zduńska Street, a couple of blocks away.

We stayed there for several months, through the winter of 1939–1940. My father went back and forth by railroad to Warsaw to try to do some trading. The war was disrupting typical trade connections, so goods that were plentiful in Łowicz were now in short supply in Warsaw or vice versa. Father would carry goods between the cities, anything that was not too bulky since he had to carry them on the train. Jews were still allowed to travel at that time. He continued to avoid Sochaczew.

In Łowicz, there was fear of the Germans but there was no ghetto yet. There was a gradual tightening of the screw. The atmosphere was oppressive, yet at the same time I played with other kids in the courtyard. I remember having a party for my sixth birthday. My family was there and maybe a couple of friends I had made. We lived month to month. About a month or two after my birthday, early in 1940, Grandfather Abram and his son were arrested and, because they were among the more affluent Jews in town, they were deported. I think they ended up in Dachau. A few weeks later, Father decided that it was too dangerous to remain in town, so we packed up and went to Warsaw.

The Warsaw Ghetto

I remember reading the Polish newspapers, which were German-controlled, in the early summer of 1940, and there was big news about German victories. Everyone was talking about it. The Germans had occupied Paris! Grown-ups were depressed, and the news of the war had an effect on me as well; it was depressing but I wasn’t scared. The Germans were limiting the rights of Jews and making our lives more oppressive. New restrictions on Jews were announced frequently, each one warning that non-observance would be punished, including by death. In the previous November, the Nazis decreed that Jews above the age of ten had to wear an armband; I was too young and never had to wear one. In November 1940, the walls around the ghetto in Warsaw — which the Jews were required to pay for — were completed. All entrances to the ghetto were controlled by Germans in uniform or Polish police. Our apartment was inside the ghetto, and one entrance was right at the corner where we lived.

We had brought some assets with us: linen, furs, silver cutlery, jewellery, gold. I’m sure there was some cash as well — probably American dollars, which were forbidden. Father thus had the means to do business and make sure that his family did not go hungry. Everything we owned at that time could be packed in three or four suitcases.

At first, life in the ghetto for people like us who had some means — cash or other assets to sell or trade — certainly wasn’t good but somehow went on. Once, as I was going to my maternal grandmother’s, I had some tomatoes in a paper bag and somebody ran by and grabbed the bag from me; he ate the tomatoes as he ran away. These thieves were common.

There were no real schools, but some Jewish groups organized one-room informal schools. There was one in the building where we lived. Before the war, my father had sent me to a cheder, a Jewish school,but my mother took one look at it and said that it wasn’t for me, and so the teacher came to teach me at home. He taught me the aleph-bet, the Hebrew alphabet; I learned it quickly enough but wasn’t much interested in reading the siddur or Chumash. The first prayer I was taught when I was very, very small was Modeh Ani, which is said immediately upon waking up in the morning.

When the weather was good, we kids often played outside, usually in the courtyard. My best friend in the building was Bolek, who lived a couple of floors above us. He had a mother who was well-educated, but in the ghetto she had no resources. I don’t know where his father was. Bolek often ate with us because we had food.

Most people were not so fortunate. The Jewish administration of the ghetto issued monthly food cards, but the amount of food obtainable with these cards was tragically laughable.

***

It was now the middle of July 1942. Gradually the net tightened. First the very poor and the homeless were rounded up. At the beginning there were printed flyers announcing that people would be relocated to the east. The announcements stated that everyone who showed up voluntarily at the Umschlagplatz, the gathering place for deportation, would be given a kilo or two of bread and some ersatz honey. I said goodbye to Bolek; his mother packed up some belongings and they went by rickshaw to the Umschlagplatz. Some people believed that things would be better wherever they were relocated than in the ghetto. From the Umschlagplatz they were transported to Treblinka. We didn’t know that they were going to the gas chambers; the German line was that we’d be resettled somewhere else. However, the news that Adam Czerniaków, the head of the Judenrat (a Jewish council used by the Nazi administration to control Jewish communities in ghettos), committed suicide because of the deportations shook everyone up, my father included. People had no specific knowledge that the deportations were to gas chambers, but most felt that it was something more sinister than a mere “resettlement.”

There were Jewish police in the ghetto who would come to the courtyard and call out for certain groups of people to come down. My father was out working on the “Aryan” side most days; he’d obtained a piece of paper that said he was employed there so that he and his family should not be deported. One day, the Jewish police went door-to-door, ordering many people to assemble in the courtyard. My mother started shaking and dressed me in warm clothes even though it was the middle of the summer. Mother was very afraid. When a Jewish policeman came to the door, Mother showed him the papers Father had obtained. After inspecting them carefully, the policeman warned her that he would accept them now but that she should not rely on these papers to avoid being taken in another roundup. That night, after my father came home from work, he and some others in the building organized a hiding place in the attic. From then on, whenever we heard the police were coming, we ran upstairs and sat in the hiding place. Sometimes we spent hours there, just sitting quietly. I had whooping cough at that time; it was very hard not to cough, but I had to be quiet.

When we started to walk out of the ghetto, I made a small wave toward Mother with my left hand, keeping it low to not attract attention. This was the last time that I saw her.

Hiding through the Uprising

Father had made contact with a Polish man to hide us. I forget his name but remember that he was a middle-aged, middle-class man. He also lived in Mokotów, near Father’s workstation outside the ghetto. We sent a messenger to him that evening. The man came and walked with me to his apartment. Later I was told that he returned to take my parents and hid them in his apartment’s cellar. I had to stay inside the apartment all of the time: I was in hiding. I knew that my parents had not been rounded up; I knew that they were hiding somewhere.

The apartment where I was hiding was on the ground floor. It was comfortable, with two rooms and a kitchen. In the evenings I put a small mattress down on the floor in the living room to sleep on. I played with their Siamese cat. There was a stack of pre-war monthly magazines published by the Liga Morska I Kolonialna (Maritime and Colonial League), which I read cover to cover. The Liga advocated expansion of the Polish marine and navy troops. The magazines had detailed descriptions of warships. The woman in the house gave me a Catholic prayer book, and I memorized the common daily prayers. In the evenings, I said them while kneeling in front of a painting of the Virgin Mary. I also learned to make the sign of the cross. In my mind this was worthwhile knowledge, given its value for potential survival.

I stayed in this apartment for a couple of months. Later, Father told me that as a consideration for keeping us he’d given this man all his furs.

After the two months or so, the man took me, along with my parents, to Czerniaków-Siekierki — another suburb a little south of Warsaw near the Vistula River — where there was still a compound with Jewish workers. Before the war, this was a farm meant to train chalutzim (pioneers) in agricultural work prior to their moving to a kibbutz in Eretz Yisrael, the Land of Israel. There were probably more than a couple of hundred of Jews there. I was somewhat surprised that this workstation had not been liquidated.

By then it was mid-November 1942 and bitterly cold. We stayed in a large unheated barracks with many other people. In the evening we laid out some shmattes on tables and slept on them fully dressed. This was when Mother told me that the rounded-up Jews had been transported to gas chambers in Treblinka, not far from Warsaw.

Within this compound there was a small apartment building. Father had managed to arrange for us to stay in one of the hallways in the building, just outside the one-room apartment where a man named Mr. Kaplan lived. The hallway was much warmer than the barracks. Although we slept on the floor, I felt that we had moved into the lap of luxury. We could cook something warm to eat once a day. However, we were in the hallway for only a few days.

In mid-December, the Czerniaków workstation was ordered liquidated, and we all had to go back to the ghetto. After the final selection, there were no deportations for several months. So, back to the ghetto we went. As people were being deported and the ghetto population decreased, the Nazis simultaneously decreased the size of the ghetto. At its height, the total population of the Warsaw ghetto had exceeded 400,000 people; in September 1942, perhaps 60,000 Jews remained in the ghetto, and by the time we returned in December, approximately 70,000 were there. Even with the size of the ghetto changing and shrinking, it was not nearly as crowded as it had been before. There were many vacant apartments in the ghetto now. I do not remember seeing any beggars then; the streets were almost empty. We moved into a vacant apartment — one large room — on an upper floor so that if there was a need to hide we’d be closer to the attic. We could have had a larger apartment, but what for? We had few possessions and there was little heat.

***

On January 18, 1943, deportations started again, lasting three or four days. About five thousand Jews were taken. My parents and I went quickly to the pre-arranged hiding place in the attic. There were no stairs to the attic, only a ladder that was pulled up after the last person. Through the small attic windows, we could see German soldiers walking on the roof of the building across the street. We sat in this attic most of the time, though Father went out on the street in the evenings for news about what was happening with the deportations.

The building we lived in was mostly occupied, but the two buildings next door were mostly empty, so I would rummage through the vacant apartments and take books to read. The people living in our building started to organize a proper hiding place. One part of the main floor hallway was on a level two stairs below the other part. These two stairs were made to be removable and underneath them a ladder was installed descending to the basement. That’s where we were planning to hide during the next round of deportations. When a Jewish engineer was brought in for consultation, he took one look and immediately guessed that the entrance was under the two stairs. Still, we spent many nights sleeping in that basement. It was a relatively elaborate place, designed to hide sixty or seventy people. Every family had assigned bunks. There was common storage of water but each family had its own cache of food. We kept clothing there as well. For use in emergencies, Mother had sewed us small bags with strings that could hold a little food and a few banknotes. We’d wear that bag against our bodies; I wore it around my neck most of the time.

***

Notwithstanding the elaborate hiding place in the building, it was clear that to be safer we needed to hide on the “Aryan” side, that we needed to escape the ghetto. Father kept trying to make contacts there. One day, in the courtyard of the building in which he was then clearing and sorting abandoned goods, he met a Polish man by the name of Zywicki, who was involved in the left-wing faction of the underground. Zywicki walked up to Father and asked him if he knew a certain person from Sochaczew. Father, being from Sochaczew, saw this as an omen that he should keep talking with this person. He attempted to persuade Zywicki to help us hide on the “Aryan” side. The big issue was not how to leave the ghetto, which was dangerous but doable; how could we survive once we got out?

Father kept meeting with Zywicki, trying to persuade him to hide us, and he finally said that he would. I was to go to him first and my parents would join me after Passover. Early on the morning of April 2, I joined Father’s usual work group, leaving to sort goods that had been left behind in the former part of the ghetto. The organizer of the group knew why I was coming along and wished Father good luck. The group marched in the centre of the road toward the gate. Father and I stayed in the middle, hoping not to attract attention to me. Mother followed discreetly on the sidewalk. As we approached the gate, the German soldier in charge walked up to us and quizzically looked down at me. I calmly looked up at him. He seemed to be nine feet tall. The head of the group spoke with him, explaining that I was his messenger boy. When we started to walk out of the ghetto, I made a small wave toward Mother with my left hand, keeping it low to not attract attention. This was the last time that I saw her.

We went to the building being cleaned on that day. Zywicki was to come for me mid-morning. I waited in the room on the main floor where books were being stored and picked up a book to read. It was The Prince and The Pauper, which I found to be very engaging. When Zywicki came to the courtyard, it was arranged that I would walk out on the street with an empty milk bottle in each hand. I would turn right after leaving the gate and walk to the corner of the block. There, I would be approached by Zywicki’s daughter, who would recognize me by the empty bottles. We met as planned. She was about seventeen years old and friendly. We walked to their place, a two-bedroom main-floor apartment not far from the Warsaw West train station. Along the way, I dropped one of the bottles.

As Zywicki was going back to tell Father that the “transfer” was successful, I asked that he bring back the book that I had started reading, but he didn’t. Zywicki was expected to organize something to hide my parents in a couple of weeks’ time. I stayed in their house like one of the family, but I never went outside. When there were visitors, I went into another room. Nobody except the family knew I was staying there.

On April 19, 1943, there was major news. The Germans had commenced another round of deportations and the Jews were fighting back. It was the beginning of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. I was nine years old then and realized that I would likely not see my parents ever again, but I had to push this thought to the back of my mind and carry on. Zywicki’s wife became very agitated about keeping me, as she was worried about her own family. They were in extreme danger if it was found out they were hiding a Jew. Zywicki and his family thought it was now too risky to keep me any longer in his apartment. He had some relatives or friends in a village in Gmina (township) Rybno in the countryside southwest of Warsaw, near Sochaczew. They went there from time to time to buy food. A few days after the commencement of the uprising, he and I travelled by train to Sochaczew, a ride of close to two hours. Then it was a two-hour walk to his friends in the village; this was the start of my year in hiding.

***

I hadn’t seen Father for over two months. I had left the ghetto on April 2, and it was already late June. When we finally reunited, Father started telling me about his experiences. He talked about what had happened with him and Mother. The Germans were going to send the remaining population of the ghetto to Treblinka and liquidate the ghetto. Organized groups of armed Jews were fighting them. My parents were hiding with others in the “state of the art” basement shelter, but it offered no protection from grenades, fire bombs or sniffing dogs. A couple of days into the uprising, the Germans discovered our shelter and shouted, “Raus! Raus!” (Out! Out!) Our nook was against the wall at the far end of this cellar. In the building on the other side of the wall, there was also a cellar with about fifty or sixty people hiding in it. Somehow, my father and mother found an opening in the wall and crawled through, into the adjoining cellar, which had not yet been discovered by the Germans.

After this, they tried several times to get out of the ghetto through the sewers, but they were not successful. One time, they went into a branch of a sewer that was very narrow. They had to crawl back to the ghetto for a considerable distance. Father said that others who went into the sewer even once and failed to escape did not want to try it again. He did it seven times in his attempt to reconnect with me, knowing that I could not survive alone. Otherwise he would have also given up. On one of these attempts, the Germans threw gas grenades through the sewer access holes when the group was below. Father had the presence of mind to put his face immediately into the water so he wasn’t overcome by the gas, but Mother was overcome and died there. He took what little she was carrying, slipped the wedding ring off her finger, and returned to the ghetto.

Back in the ghetto, Father joined a group of fighters who were then also trying to leave the ghetto through the sewers. He eventually made his way out and onto a truck that took him to join partisans in the forest.