Blog

In Search of Light

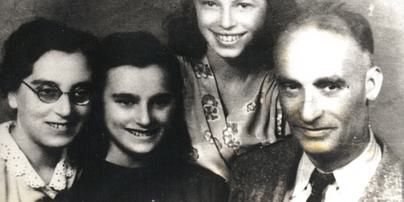

The Abel family after the war. From left to right: Martha's sister, Eta, her mother, Sari, her father, Ödön, and Martha. Cluj, Romania, cira 1946.The End of My ChildhoodAfter the Nazis took power, they confiscated part of our house and gave it to German army officers, including a number of SS. Once, a German officer told my father, “Herr Doktor, wir haben das Krieg verloren.” (Doctor, we have lost the war.) My father was absolutely terrified. He couldn’t say yes and he couldn’t say no; he didn’t know how to react because it could have been a provocation. Remember that this was 1944, late in the war, so some soldiers might have realized that the war was not going all that well. But Hitler’s propaganda was extremely powerful and effective nonetheless. At one point, the German officers told my mother and father that they wanted to have a party in our house and that my mother should cook for them and my father should help with the cleaning. My parents were not allowed to leave, and they were very afraid that the soldiers might get drunk, and then God knows what might happen. My parents told me to leave the house and stay overnight with some friends, and they also told me that if the officers killed them that night, I should go to a certain person who would help me. I still remember vividly that, at ten years old, I did not cry; at this point I felt like I was an adult looking at the world the way it was, not the way it had looked in my childhood dreams.In early May, the second of the month, a high school teacher, an ethnic German, came and knocked on the window of our house and told my father that the next morning we were going to be taken away. There was nowhere to go, there was nowhere to hide, and so we just got up and packed during the night. But before getting to this point, the preceding months had been so terrifying that I don’t actually remember when I grew up. I just knew that over a period of a few months, I was no longer a child.Indeed, on the morning of May 3, 1944, members of the Hungarian csendőrség (gendarmerie) came to our house, forced us to unpack and take less than we had planned — allowing for only one change of clothes — and put us in a truck to be carried away. In the truck, an officer noticed that my parents still had their wedding rings on and said that they were not allowed to keep them. My dad then took off my mother’s wedding ring and his own and threw them on the road. Interestingly, and very touchingly for me, these are the only things that survived from all our belongings. Everything else disappeared, but my parents found the two wedding rings in an envelope at the city hall when we got back.The gendarmes took us to a ghetto in a brick factory some distance out of town, where, among the Jews, they were two of three medical doctors. When we got there, an SS officer took out his gun and, holding it against my parents’ heads said, “Well, if somebody escapes, I am going to shoot you, or you, or you.” I watched that, and the image is still vivid in my mind. But nobody had a chance to escape. It was just another way to terrorize us.About the AuthorDr. Martha Salcudean was born in 1934 in Cluj, Romania, and immigrated to Canada in 1976. She was a professor at the University of Ottawa and head of mechanical engineering at the University of British Columbia. She has received three honorary doctorates and a number of prestigious awards and honours. Martha Salcudean is professor emeritus at UBC and lives in Vancouver.Martha’s memoir is available for purchase here.

Stories of Pesach: Holocaust Survivors Remember

Pesach, or Passover in English, often figures prominently in the stories of authors who survived the Holocaust as children. Introduced at an early age to the cultural and religious traditions of this celebration, the authors share the customs and flavours associated with these happy childhood experiences, memories that are both joyful and nostalgic.The following excerpts from our books illustrate how Pesach was celebrated across Europe before the war. The depictions testify to both a common cultural identity as well as the great diversity of Jewish communities. The excerpts also show that many Jews continued to celebrate Pesach even during the Holocaust, sometimes in precarious conditions — celebrating their Jewish identity and resisting discrimination and persecution. Pesach remains a time of celebration for our authors, an opportunity to continue family traditions in the country that welcomed them after World War II.Pesach, a celebration of traditions Pesach commemorates the liberation and exodus of the Israelite slaves from Egypt during the reign of the Pharaoh Ramses II. The spring festival lasts for eight days and begins with a lavish ritual meal called a seder on the first two nights. During the seder, the story of Exodus is retold through the reading of a Jewish religious text called a Haggadah. With its special foods, songs, and customs, the seder is the focal point of the Passover celebration and is traditionally a time of family gathering.During Pesach, Jews refrain from eating chametz — anything that contains barley, wheat, rye, oats or spelt that has undergone fermentation as a result of contact with liquid. Avoiding chametz commemorates the escape from Egypt, when Jews did not have time to let their bread rise. Before Pesach, Jews also clean their homes to remove these foods, as well as anything that has been in contact with them. Separate dishes that have never been in contact with chametz are used only for Pesach.Born in 1931 in Paris, France, Muguette Myers recounts in her memoir, Where Courage Lives, the different Pesach traditions of her childhood. Her maternal grandparents, the Fiszmans, were very religious, but her paternal grandparents, the Szpajzers, were non-practising, which sometimes gave rise to funny situations during Pesach.“At Pesach, or Passover, all vestiges of non-Passover food, even crumbs, have to be searched for and removed from cupboards. All dishes have to be changed for Passover dishes. While the Fiszman household was busy cleaning, the Szpajzer couldn’t have cared less. One Pesach, it just so happened that Gromeh [grandmother] Fiszman came to visit the Szpajzers. Their windows looked out on the courtyard and they could see Gromeh making her way to their apartment. Gromeh Szpajzer ran to a neighbour who was as non-practising as she was and they quickly exchanged kettles as well as several cups, saucers, forks and spoons so Gromeh Fiszman would think that the dishes had been changed.”Muguette also has excellent memories of the Jewish culinary specialties she enjoyed during Pesach:“When Passover came we had matzot [crisp flatbread made of plain white flour and water that is not allowed to rise before or during baking], chicken soup with matzo balls, and gefilte fish [a dish generally made from chopped whitefish that is made into patties and boiled]. Gromeh also made her own raisin wine for Pesach, a process she started right after the Rosh Hashanah holiday. She let it ferment and then filtered it; then she let it rest another month and did the filtering again. She repeated this process about three more times before the wine was ready for consumption. I loved this wine. When I stayed with her and whenever visitors came, I was allowed a very small glass at mealtime.”Muguette at age 9 (seated, left) with her family in Paris. In the back row: Muguette’s aunt Deeneh (left) and Muguette’s mother, Bella. In front (left to right): Muguette’s maternal grandmother, her brother, Jojo, and her uncle Yidele. 1940.George Stern describes in Vanished Boyhood the kosher wines that his family donated to the less fortunate of Jews of Újpest, Hungary, on Passover:“One Passover tradition asks that if people can afford to, they provide those less fortunate with foods that are eaten during the holiday, like matzah, eggs, chicken or wine. My father, Ernő and Uncle Jenő kept that tradition by putting aside one barrel of kosher wine from their vineyard. Just before Passover, poor families could come to our courtyard, where our wine store was located and collect as much wine as they needed. When I was eight years old, I was eight years old, I was given the honour of giving out the wine to them and I filled the bottles they brought, one by one. This took almost the whole day because we gave away a few hundred litres of wine, but I was glad to do it because it was a mitzvah, a good deed.”George (second from the left) with his father, Ernő (left), his sister, Ágnes (second from the right) and his mother, Leona (right).Although she also attaches great importance to food, Ann Szedlecki emphasizes the other annual customs of Passover in the Jewish quarter of Lodz, Poland. Her memoir, Album of My Life, describes Ann’s last family seder before the war.“In the spring of 1939 the annual rites of the season began as they did every year when the housewives dumped the old straw from the mattresses and replaced it with fresh smelling straw. This meant that Passover couldn’t be far off.For Passover, I was always outfitted with new clothing — new ribbons for my braids, new underwear and socks, a dress and new shoes.[…]Preparations for Passover could be seen and felt everywhere. The wooden floor of our kitchen — which was where my father worked as well as where my mother cooked — was scoured with sand to get out the oil stains left by the sewing machines. Red wax was applied to the floor and allowed to dry, Finally, a heavy polisher was pushed manually across the floor to give it a shine. My mother distilled homemade wine, drop after drop running through clean linen, leaving a deposit. The linen was changed few times until the wine was clear. She also prepared a large jar of cut-up red beets and water — the water would ferment and be used in place of vinegar, which wasn’t allowed because it is a product of wheat, or chametz, which is forbidden on Passover, and the beets were used for our borsht (beet soup). Our large laundry basket, by now well scrubbed and lined with a large white sheet, was ready to store the matzah (unleavened bread). We had special Passover dishes and cutlery, but we didn’t have a Passover set of pots and pans so our everyday set was made kosher by a man who pulled a wagon containing metal vats with hot water. After the pots and pans were dipped in the water, the cookware was declared kosher for Passover.After all these preparations, we followed our father through the house on the evening before Passover. With candles in our hands — he held a feather — we went through every corner to get out the last bits of chametz trapped in the crevices. We would follow the traditions of burning any last chametz we found the next morning.By noon the next day, everything was ready for the festivities. The beautifully ironed white tablecloth, the polished sterling silver candlesticks, the arm chair where my father would sit leaning on a huge pillow at the first seder that evening. On the table were china, cutlery napkins, wine glasses and a plate of matzah covered with a beautifully embroidered cover set before my father’s seat. A traditional round seder plate held a roasted egg, a shank bone, bitter herbs and so on. Mouth-watering smells emanated from the kitchen all afternoon. My stomach growled, but it would have to wait. My sister, her husband and the baby soon arrived. There were six adults, but only four chairs. The lounge was put against the table for me and my brother, Shoel.The seder began when the women lit the candles, said the blessings and the Haggadot [a book of readings followed at the Passover seder service] were opened. My brother asked the Four Questions, even though I was the youngest (except for the baby). I checked Elijah’s cup to see if he had drunk from it. The seder prayers and readings went smoothly until we reached the song ‘Dayenu’ [a traditional song of gratitude that is sung during the rituel meal, or seder]. As long as I could remember I always giggled when I heard this song. This year, I was almost fourteen years old and an aunt and I hoped that I had outgrown the laughing. No such luck. As we got closer to singing ‘Dayenu’ my father’s blue eyes beneath bushy black brows fixed on me as if asking to behave. I got up from the table, my hand over my mouth, and when I reached the kitchen the giggles I was holding back erupted.”The last photograph, taken in Bolimów, Poland, that Ann received from her family in the Warsaw ghetto. Left to right: Ann’s father, Shimshon Frajlich; Ann’s mother, Liba Bayla Frajlich, holding her granddaughter, Miriam; Ann’s sister, Manya; and her two aunts, Tauba and Sarah.Pesach under the Anti-Jewish Nazi Legislation (During the Holocaust)Pesach traditions were shattered by the Nazis’ antisemitic laws. The Nazis orchestrated the annihilation of the Jewish population of Europe and, consequently, the systematic destruction of Jewish cultural and religious heritage. Despite this oppression, Jews strove to maintain the practice of their customs and rituals, to preserve their human dignity and identity. The following excerpts illustrate how, during the Holocaust, Pesach celebrations gave rise to a form of spiritual resistance, even in the most difficult circumstances.On April 19, 1943, the first night of Pesach, Warsaw ghetto resistance fighters attacked German soldiers in a revolt, better known as the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Seeking refuge in a secret underground shelter, Pinchas Gutter’s family made a seder, seeking to find, through this ritual, peace and comfort.“We existed … by hiding, until April 19, 1943, Erev Pesach, the eve of Passover, which was also the eve of the uprising of the Warsaw ghetto. That day, there was an alarm. The few telephones that existed in the ghetto were still somehow working — these were mostly in apartments where doctors or other people deemed important lived — and the Polish underground resistance on the outside who were working with the Jewish underground phoned someone in the ghetto to say that the Nazis were coming in to take everybody out. By that time, there were already lots of bunkers in the ghetto. We had also prepared a bunker underneath the ruins at the front of our building. The caretaker and the men in our building, including my father, had dug it out, creating a middle section as an entrance and a room on either side. They didn’t want to give up and be taken by the Germans and so they put in food, electricity and water and air vents so the bunker couldn’t be discerned from the outside. My father and mother prepared us children for when we would have to go there. They told us that when the time came to go into the bunker, we were to ask no questions and we must get ready as quickly as we could. That day, we all went down to the bunker, about 150 people in all. … My father must have brought wine, somebody else had matzos, and that evening in the bunker, they made a seder. Everyone was crying and praying. These were religious Jews who knew by heart the Haggadah, the Jewish text that sets forth the order of the Passover seder, and it still amazes me that, at such a dire time, they never forgot their culture and their morals. They also always made sure to shelter and look after their children.” – Pinchas Gutter, Memories in Focus“In April 1942 we had twenty-two Jewish partisans in our group. Because we had all lost our own families, we felt like a family — we became brothers and sisters to one another. One of the Jews in our group, Moishe Abramowitz, who had escaped from the town of Bobruisk, had brought with him a small prayer book that he kept hidden in his boots. He helped our group cope with the difficult conditions in the forest and the tragedy of our people. Reminding us that Passover was fast approaching, he managed to obtain some beets to make a red soup to substitute for wine, traditionally used during the holiday ritual. We had no matzah, but he dug up some horseradish from nearby fields. On the night of the first seder, we gathered near our underground bunker.As I was the youngest, it was decided that I would ask the Four Questions, the Ma Nishtanah. I knew them well since, as the youngest in my family, I had always been the appropriate candidate. Here in the forest I interpreted the answers to the questions somewhat differently. In answer to the question, ‘Why is this night different from all other nights?’ I replied, ‘Because last Passover all the Jews sat with their families at tables beautifully set with matzah and goblets of red wine. Last year, each of us had a goblet on our plate and listened to the oldest person in our household conduct the seder. Tonight, in the forest, our lonely and orphaned group, having miraculously survived, remembers our loved ones who were taken from us forever.’ Tears fell from our eyes. After this, we continued to keep the traditions of all the Jewish holidays, which gave us the courage and the will to survive. With God’s help, we would eventually live in this world as free people.” - Michael Kutz, If, by miracleMichael (front row, on the right) with the partisans. Lodz, circa 1945.Pesach in CanadaMuguette Myers was in hiding with her family during the Holocaust. In 1947, she immigrated to Canada. Today, although she is non-practicing, she enjoys celebrating Pesach with her children, her grandchildren and her great-granddaughter. She enjoys the traditional Jewish dishes prepared by her daughter, who sustains the culinary and religious heritage of her grandparents, the Fiszmans. Muguette also treasures the traditional recipes of her childhood, written by hand by her mother, which she generously agreed to share in this article.

A Tapestry of Survival

Leslie (right) with his brother Louis (Lali), holding their nephew, Adamka. Budapest, 1944. The War One day I went to visit a friend in the apartment house in which we had first lived when we fled to Budapest. While I was there, a troop of Hungarian soldiers came in to the centre courtyard of the building and were lining up all the Jews to take them away. I started walking toward the exit gate. A soldier stopped me.“Where are you going?”“I’m leaving. I don’t live here.”He scowled at me, “But you’re a Jew!”“No, I’m not,” I said. “So what are you doing here?”I knew that telling him that I was visiting a Jewish friend would not help my cause. Just in time I remembered that air-raid sirens had sounded right before the soldiers arrived. “I came in when the air-raid sirens started.”An officer came by, and the soldier told him my story. “Aw, don’t bother. Let him go,” he said.As the soldier escorted me to the exit, he said, “I still think you’re a Jew.”And I replied cockily, “To err is human,” and walked out to freedom. I was so proud of my cleverness that this story later became my first piece of published writing, in my high school yearbook. It is only in the last few years that I allowed myself to realize how close I was to being taken away by the Hungarian soldiers; my family would never have found out what had happened to me. There were many close calls, and I think it took quick thinking and miraculous escapes to survive those times, as well as a strong will to live. But I was not aware of these things at the time. We all just did what we had to. About the AuthorLeslie Mezei was born on July 9, 1931, in Gödöllő, Hungary. In 1948 Leslie arrived in Canada, where he completed high school and then graduated with a bachelor’s in mathematics and physics from McGill University and a master’s in meteorology from the University of Toronto. After working as a systems analyst and manager from 1955–1965, Leslie became a professor of computer science at the University of Toronto. An early pioneer in the field of computer art, Leslie’s articles were regularly published in Computers and Automation and Artscanada. He also developed two new graphic programming languages and produced innovative computer art, which was exhibited internationally. Leslie married Annie Wasserman in 1953 and raised two children with her before she passed away in 1977. Leslie now lives with his wife, Kathy, in Toronto, where he is involved in an interfaith and interspiritual movement, the mission of which is to promote a message of unity in diversity, and he published the Interfaith Unity News for a number of years.

Lovers in a Dangerous Time

From Anka Voticky’s Knocking on Every DoorArnold and Anka with baby Milan, 1934. To my husband, Arnold. They say m...

Remembering Kristallnacht, Eighty Years Later

Remembering Kristallnacht through the Stories of SurvivorsOur authors testify to the rising persecutions that preceded Kristallnacht, along with describing Kristallnacht itself.Born in Cologne, Germany, in 1928, Margrit Rosenberg Stenge was a child when she first experienced the impacts of Nazi antisemitism. Forced to pursue her education in a Jewish school, she tells of her worries in her memoir Silent Refuge:After changing schools, I came to realize that there was a certain stigma attached to being Jewish. I overheard conversations between my parents about Hitler and the antisemitism he preached, even though they did not yet believe that this had anything to do with them … But as Hitler’s voice was heard more frequently on the radio, my father grew exceedingly upset over Hitler’s ranting and raving, which for the most part was directed against the Jews. (8)As Margrit recounts, Nazi policies intended to humiliate the German Jewish population were quickly followed by acts of violence and vandalism, foreshadowing the events of Kristallnacht.Fred Mann remembers Kristallnacht and the destruction of the Jewish neighbourhood in Leipzig in his memoir, A Drastic Turn of Destiny:Fred Mann’s German identity card issued in Leipzig, July 11, 1939.The wealth of information and symbols of tradition that not only recorded Jewish life in Leipzig but across Germany went up in smoke that night. (39)Walking through the city it was incredible to discover the burned synagogues and the Jewish-owned stores smashed and plundered. The Jewish district of Leipzig … suffered the worst fate. There was hardly a Jewish store owner or wholesaler who did not lose all his or her assets that night. The destruction was not only total but systematic. (44)Kristallnacht was not only the burning of synagogues and the destruction of Jewish property but a test that demonstrated the effectiveness of many years of anti-Jewish propaganda used to brainwash the population. The general population showed no reluctance to participate in the destruction and the photographs of German people’s faces taken during this unpunishable “freedom to destroy” speak volumes. We are frequently told that not everyone engaged in the horrendous events of that night, but when one looks at the spectators, one realizes that their facial expressions aren’t very different from those of the perpetrators. Nor can one excuse the rest of the world for not taking measures to challenge the Germans and to express the total unacceptability of these acts. When could we expect decent human beings to take a stand on matters of wilful and planned destruction and death? (44–45)In his video testimony, Joseph Schwarzberg recalls Kristallnacht at age twelve in Leipzig.Joseph Schwarzberg’s memoir, Dangerous Measures, is set to be released on November 25, 2018, and will be available for order here.Eighty Years LaterIn the current political climate, it is our duty to remember Kristallnacht, which serves as an important reminder of the need for tolerance and respect for others. For anyone wanting to participate in this commemoration, events are being held across Canada, including in Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal.Learn more about the personal experiences of Holocaust survivors whose memoirs have been published by the Azrieli Foundation.

Preview: Flights of Spirit

Children working in an ORT carpentry workshop in the Kovno ghetto. Elly Gotz is in the centre. Syringes on a TrayThe most dramatic event in my life happened in the summer of 1944. I was sixteen years old and I was facing my death. In wartime, death can occur at any time. But today, death would come not from the hand of my enemy — it would come from the hand of my beloved mother.I was hiding in a basement with my mother, my father, my three uncles and my aunt. We had covered the entrance to the room with an old cupboard and we sat there listening to every sound coming from outside. We had all agreed that we would rather die here than be captured and shot on the killing fields of the Ninth Fort in Kaunas, Lithuania.My mother, who was a surgical nurse in the ghetto hospital, had been given the task of arranging our communal suicide. She had filled several syringes with a potent heart drug. The plan was to inject an excessive dose of the drug in our veins and cause a heart attack.I watched my mother as she prepared a serving tray covered with a clean white cloth. On the tray, there was a bottle of medical alcohol and beside each syringe lay a ball of cotton wool. I thought this was funny, so I reminded my mother that as this was a final injection it did not have to be a clean one. Everyone laughed, except my mother; but she took away the cotton wool.It was very boring to sit for days on end in that dim basement. I had a lot of time to think and I had many questions: How does it feel to die? Does the brain go on working for a time after the heart stops? My mother was a strong woman and I trusted her but would she have the strength to give me, her only child, the first injection?I tried to imagine my mother injecting the six of us and then, finally, herself. Then I tried to imagine the seven of us lying on the floor waiting for the drug to kick in. What would we say to each other? Would we laugh or cry? Would it be painful? As I tried to picture the scene, I decided it would be good to go first — I did not wish to see it. I will now try to describe the circumstances that would make a woman like my mother ready to kill her son and her family. That suicide pact came after we had spent three years, from 1941 to 1944, in the Kaunas ghetto — which became the Kauen concentration camp — in Lithuania. My story can only be understood after knowing what was happening in the Kaunas ghetto during those three years.About the AuthorElly Gotz was born in Kovno (Kaunas), Lithuania, in 1928. In 1947, Elly and his parents immigrated to Norway and then to Zimbabwe. Elly immigrated to Toronto in 1964, where he established various businesses and achieved his lifelong dream of becoming a pilot. In 2017, at age eighty-nine, he fulfilled another aeronautical dream by going skydiving.