Lovers in a Dangerous Time

Even in the years surrounding and during the Holocaust, one of the most explicitly hate-filled periods of history, love found a way to flourish in many people’s lives.

The following excerpts from Canadian authors published in the Azrieli Foundation’s Holocaust Survivor Memoirs Program show that love is an essential part of human existence, no matter how dire the circumstances.

From Anka Voticky’s Knocking on Every Door

To my husband, Arnold.

They say memories are golden.

Well, maybe that is true.

I never wanted memories.

I only wanted you.

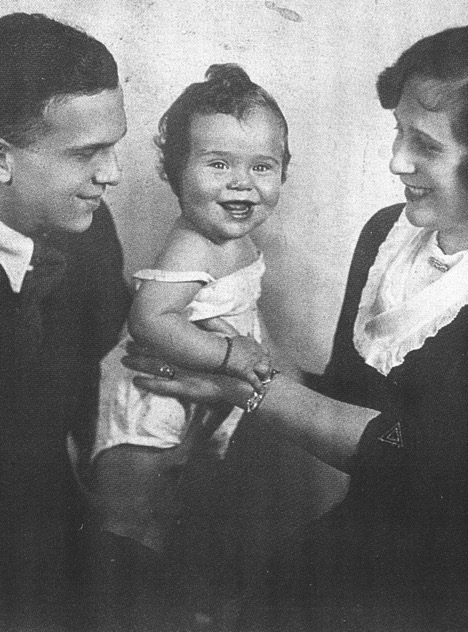

In the summer of 1929, I had just turned sixteen and was enrolled in business school for the fall. After one of my usual Sunday walks with my parents and Liza [my sister] to Stromovka Park, I met Arnold, my future husband, for the first time — he was twenty. We ran into my brother Erna just outside our house with a young man and twin girls. They were on their way to see a movie, but before they left, Erna asked my mother to give them a snack. We prepared something and set the table. The young man spoke to me, but only a few polite words.

When I woke up the next day, the maid warned me that there was trouble brewing. Apparently Erna had told my parents that his friend liked me — that he thought I was beautiful. That really alarmed my mother because she thought I was much too young to have admirers. She promptly ordered that nobody tell me anything about this. My brother obeyed, but I had nevertheless found out about it from our maid.

* * *

Some people ask me what helped me survive the Holocaust. In my case, it was my husband’s wisdom and strength to live, as well as the fact that he supported and saved my entire family. How did I adjust to normal life? I didn’t. We were in shock after the war. When we returned to Prague in 1946 there was terrible antisemitism — much more than we had ever experienced before the war. Our family had always been upright citizens and very patriotic.

My message to young people is that your whole lives should be built on honesty and loyalty to family and friends. When you choose a partner as an adult, try to give and not to expect to receive. Give to other people too and take care of the sick and the old. I did it all my life and now in my old age I get back a lot from friends and family. I believe in it.

From Bronia Beker’s Joy Runs Deeper

One day after I returned from my half-brother’s house, one of my girlfriends introduced me to a boy named Josio Beker. Josio was different in millions of ways from Itse. He was a handsome man, older, and sure of himself. He seemed so strong, not afraid of anything, like there wasn’t a thing in the world that he couldn’t do. He had everything that Itse was lacking. Itse was good company but he was a mama’s boy who depended on his parents. I got the feeling that if anyone started a fight, he would have been the first to run away. Josio impressed me with his strength and his sense of humour. I liked that a lot, but we were so different, and our families were also so different.

We were not rich — my father was only a small businessman — but I think that we were considered one of the more prominent families in town. Though I could never really understand why, shoemakers, carpenters and all the people working in trades were considered lower class. Josio’s father, a shoemaker, had died young, and his mother was left with four children. She earned a living by selling fruit in the market. When he grew up, he provided for his family. He worked very hard so that his mother and siblings were not lacking for anything.

Although Josio caught my eye, my father would never have allowed me to go out with him, let alone marry him. So I kept meeting him secretly. When I was with Josio, I felt relaxed, secure and protected. It felt to me like he had never been young, having always worked to support his family. Though we didn’t have much in common, I saw that he was smart and devoted to everybody close to him. I admired him for that, and I knew that being a good person was worth more than all the education in the world. I became quite serious about him and neglected Itse. When Itse found out that I had a new friend, he dropped me. He wouldn’t even talk to me. It bothered me because I missed our conversations and discussions, but I had to make a decision. I couldn’t have both.

From Willie Sterner’s The Shadows Behind Me

We didn’t know anything about KZ Gunskirchen, but I knew for sure from my previous experiences that we weren’t going to a hotel or a picnic. On the way to the camp, we didn’t go in columns of four because we could hardly walk. We were lucky that the SS guards got tired too, but we were still beaten up and terrorized and some of us were shot. Marching quickly with the SS guards was a huge struggle. We left many dead people behind on the road.

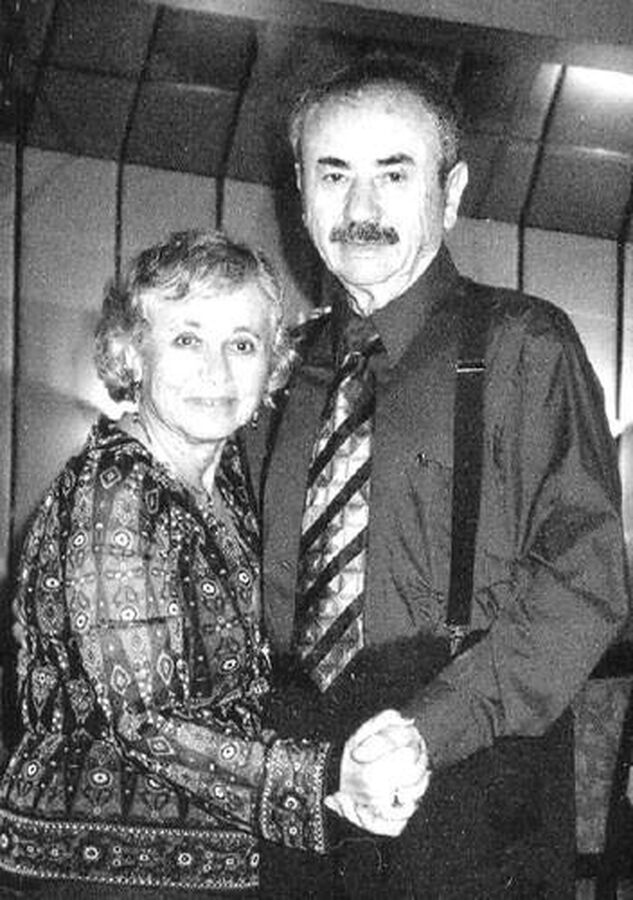

Somebody on the march pointed his finger to a young girl and told me that she was from Sosnowiec, Poland — he knew that I had family in Sosnowiec. So, as we walked, I moved closer to her for a few minutes and asked if she had met anyone from my family. She said that she was sorry, but she hadn’t. Her name was Eva Mrowka and she asked me if I knew anyone from her family, the Traimans, in Wolbrom. I said yes, I knew them well, but I was sorry to have to tell her I hadn’t seen them for a long time. Our short talk ended very quickly when an SS man came toward us. We had to separate to avoid getting into serious trouble.

* * *

As they arrived, the refugees in Wels were moved into a DP facility that was housed in a large building in Wels called Herminen Hof (Hermine’s Court). A few months after I got there, a young woman came to the camp to visit some of her friends and as soon as they saw her come into the room, they all started screaming and crying and kissing one another. I didn’t know what was going on at first, and then I realized that what I was seeing was a joyous reunion. I was happy for them. After they all sat down, excited and tired, the young woman turned to me with a nice smile and said, “Hi, Willie!” I was really surprised. I had never seen her before. Where did she know me from and how did she know my name? She saw that I was puzzled, so she came closer and reminded me that we had met on the terrible march from KZ Mauthausen to KZ Gunskirchen.

She was beautiful. She had blond hair, wore a white dress and had a friendly smile. Her name was Eva Mrowka and she was from Sosnowiec, Poland. On that march, however, she hadn’t looked as beautiful as she did now. She had looked like a beggar — dirty, tired and hungry (and I had looked the same). I had hardly noticed her beautiful face. I was glad to see her as a free young woman in a better place than Gunskirchen, to meet her again in the DP camp. But I would never have recognized her. On the march from Mauthausen to Gunskirchen, I had been miserable and hadn’t paid any attention to women, but in the DP camp I certainly did pay attention to Eva Mrowka. She had just come out of hospital where she had been recovering from lengthy illnesses, including typhoid. She was planning to stay in the DP camp in Wels with her friends.

Eva and I became very close. We were both alone — neither of us had any family there — and I saw her often. A year after the end of the war, in June 1946, we made plans to marry.

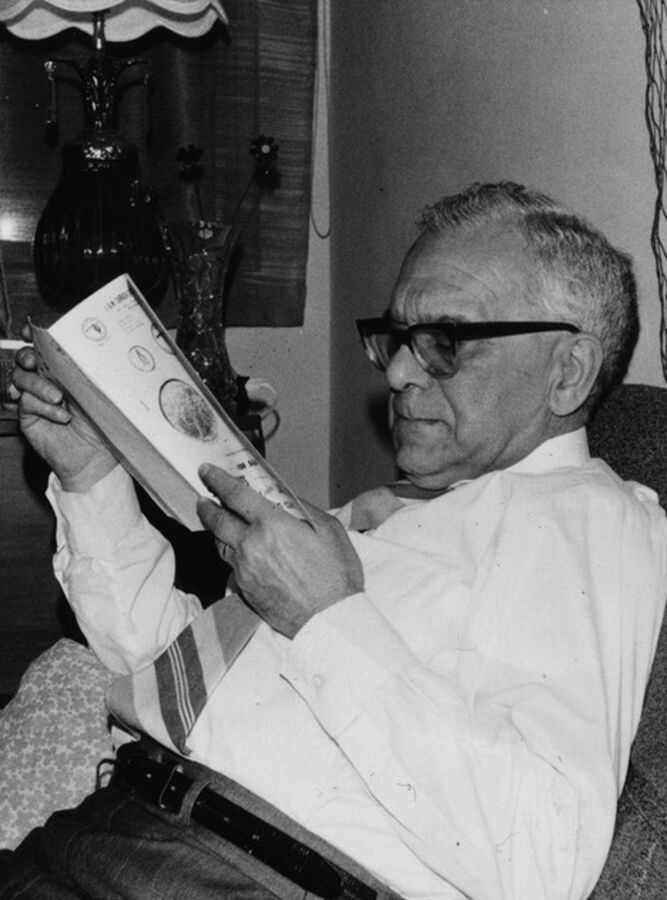

From Zuzana Sermer’s Survival Kit

By the end of 1943, five months after my mother’s passing, I felt it was time for me to flee the country. Although there had been some periods of relative calm when there weren’t any deportations, I knew I could no longer stay in Humenné alone. Soon after I was discharged from the hospital, I met the man who would become my husband, Arthur Sermer. He, his brother Victor and their cousin Leah were staying with their aunt, who happened to be my neighbour. We all agreed that remaining in Slovakia was too dangerous. All of my hiding places had been exhausted and Arthur was being hunted by the Gestapo because they knew he had been in touch with partisans on the Polish border. We decided to seek refuge in Hungary. Arthur had a contact who led us to a series of further contacts who eventually produced a smuggler who, for a sum of money, would get us across the border.

* * *

By the time the years of peril and tragedy began for the Jews, most of Arthur’s siblings had grown up, completed their education and no longer lived at home. Only the youngest two children, Sidonia and Victor, remained at home with their parents. But when the deportation of Jews to concentration camps began in Slovakia, most of the family came home to be with their parents. They chose to resist together and, along with other Jews from local villages, they decided to escape into the forests and hide. They began to prepare by collecting and storing food and supplies. The people knew the area well, so the forest was a natural hiding place. A huge tent, hidden deep in the woods, became home to thirty people of various ages — men, women, boys and girls. The group moved into the woods toward the middle of May 1942. They gladly endured the inconvenience of life in the woods, all in the one tent, but it was to be short-lived. The hiding place extended their lives by only about six weeks.

Shortly before the end of June, the group learned that they had been betrayed. They were beginning to pack up to flee when suddenly the Slovak gendarmes arrived. A few shots were fired into the air and the police, using loudspeakers, demanded their surrender. In a panic, the unarmed people began to run in all directions. Twenty-three were captured and taken to the nearest railway station, where a transport train awaited them.

Among the seven who were able to escape deeper into the forest were Arthur and Victor. At the time, Arthur was thirty and Victor was eighteen. They found the other members of the group and began to search for a new hiding place. They stayed in the forest for just over a year, but eventually the situation became intolerable and members of the group separated. It was not long after that I met Arthur, Victor and their cousin Leah, and we began to plan our escape to Hungary.

From Rachel Shtibel’s The Violin

As is customary in a Jewish Orthodox wedding, Adam and I fasted the day before our wedding and were not permitted to see each other for the twenty-four hours prior to the ceremony. Adam stayed at my parents’ house and I went to stay with my mother’s cousins, Isaac and Ewa Zweig. The morning of the wedding, June 24, 1956, I came home to find the entire apartment transformed.

Regina and Shiko’s small living room had been turned into a bride’s room. In the corner there was an armchair covered with a white sheet. It was surrounded by an ocean of flowers and behind it the walls were decorated with mirrors. This is where I was to sit and greet all the women who came in. I felt like a princess. Breathlessly, I awaited the evening.

Adam was a very handsome groom in his navy blue suit and white bow tie. His black wavy hair shone and his wonderful smile brightened his whole face. In his warm, dark eyes I could read his happiness and undying love for me. It only added to my joy that my parents also loved Adam and already considered him a son. Finally, Adam’s prayers would be answered. He would once again be part of a warm and loving family.

My princess-style wedding dress was a soft, off-white gown with a long lace veil. I carried a bouquet of fresh white roses that matched the wreath I wore in my hair. As I walked on the white sheet covering the floor, toward my future, the children walked in front of me, sprinkling white rose petals in my path. The house, festive and full of flowers, seemed a beautiful rose garden to me and a fitting symbol of this glorious day full of laughter and tears of happiness.