The High Holidays Engraved in Memory

As the summer comes to an end in Canada, Jews prepare for the fall High Holidays, which start with Rosh Hashanah, the new year, and also include the holiest day of the year for Jews, Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. These holidays are a traditional time of reflection for many Jews, a time to ask for forgiveness, as well as to commit to doing better in the new year. The moral values of these special days are at the heart of many Holocaust survivors’ testimonies.

In their memoirs, Holocaust survivors show how important it was to them to recognize these special days, in their communities before the Holocaust, and as a way to stay connected to who they were during the Holocaust. After liberation, as survivors came together to rebuild their lives, their families and their communities, these days of reflection and renewal took on new meanings again. Their stories offer glimpses into the diversity of customs, experiences and memories associated with these holidays. From love at first sight to religious rites and to persecution upon arrival in Canada, memories of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur take on a particular resonance in the stories of these survivors. The High Holidays remain a time of celebration for Holocaust survivor authors, an opportunity for them to gather with family and enjoy delicious culinary specialties in the country that welcomed them in the aftermath of World War II.

What Are Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur?

Rosh Hashana marks the beginning of the Jewish year, ushering in the High Holy Days. It is celebrated with a prayer service and the blowing of the shofar (ram’s horn), as well as festive meals that include symbolic foods such as apple dipped in honey, which symbolizes the desire for a sweet new year.

Yom Kippur comes eight days after Rosh Hashana and is a solemn day of fasting and repentance.

Holidays for Love and Family:

For Elsa Thon, the High Holidays remind her of the first time her parents met in 1913. In her memoir, If Only It Were Fiction, she shares this story: their love at first sight at the synagogue in Kharkov, then ruled by Russia, on the evening of Rosh Hashanah. She reveals, at the same time, how the values inspired by this feast united them through the turmoil of World War I and the Russian Revolution, until her birth.

“The Russian military allowed the young Jewish soldiers to pray during the High Holidays, Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, in a synagogue in Kharkov, close to where they were stationed at the time. It was there that my parents met for the first time. Both remembered their encounter and, separately, related exactly the same story — it was love at first sight. They prayed for the coming year to bring health and happiness, as was the custom. History followed its course, and their story unfolded…

When she met my father at the synagogue, my mother’s life changed once again. They fell in love, knowing that my father could be sent to the front line at any time. In 1913, when his departure was imminent, I presume that our parents swore faithfulness, hoping that some day he would return from the war and they would marry. They allowed themselves to dream in spite of the dangers of war. When he was called to the front line, they relied only on their youth, hope and the strong love that brought them together.

Although all this happened before I was born, the story was told and repeated so many times that it became engraved in my memory.”

Betty Rich has very different childhood memories of the High Holidays. In her memoir, Little Girl Lost, she expresses her love for the festive family traditions of Rosh Hashanah, but displays dismay at the Orthodox religious rituals practised by her mother on Yom Kippur.

“During certain Jewish holidays, such as Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year) and Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement), adults had to be in the synagogue from morning until sundown. Their children came to visit them sometime during the day. My parents, being Orthodox, were separated — women were upstairs in the balcony of the synagogue and men were on the main floor. I remember visiting my mother on those very holy days. The air was heavy and sticky and my mother, like all the women on Yom Kippur, was praying and crying very loudly. This was the day that they ask God’s forgiveness for sins committed during the whole year. I was both appalled and scared by it. I couldn’t understand why my mother would ask forgiveness for sins that, as far as I knew, she had never committed. I also couldn’t fathom the whole idea of praying, addressing God and constantly praising him, using such powerful adjectives. Why? What for? I didn’t dare to ask, so I would just fulfill my obligation to my mother, feeling sorry for her. Seeing her crying and humbling herself so much deeply touched me, but angered me at the same time.

For the most part, though, the Jewish holidays were a happy time in our family, a time of tradition and reunion that, to me, had nothing to do with religion. I used to love those holidays (except Yom Kippur, as I just mentioned). The transformation from an atmosphere of tension and worries over our constant financial problems was so great that it’s no wonder that when I was happy I used to say, ‘I feel like it’s a Jewish holiday today’.”

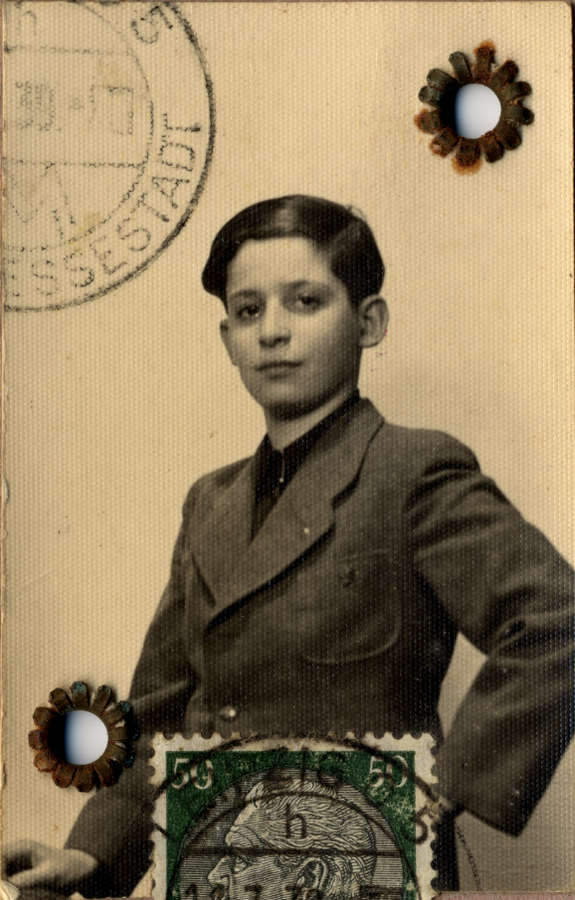

Like Elsa Thon, many survivors share holiday memories that include people and places that did not survive the war. Fred Mann shows us the traditions and dress habits of men on Yom Kippur in his hometown of Leipzig, Germany, before the war. His memoir, A Drastic Turn of Destiny, depicts the special importance for him of the prayer service at his synagogue, which was the last service Fred spent with his family before his synagogue was destroyed by arson during Kristallnacht, in November 1938.

“Our last visits to the synagogue took place on September 25–27, 1938, for the High Holidays of Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, and October 4–5 for Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. In prior years we attended every High Holiday as well as the more joyous occasions such as Simchat Torah, when lots of sweets were handed out to the children. We went to at least one Shabbat service a month, and this was always followed by a visit to the Rosenthal Park where we met with our school friends. Unlike all the previous years, in 1938 not a single man appeared in the customary morning coat or top hat...

The longest day of the High Holidays was Yom Kippur, when my parents remained in synagogue for almost the whole day. The services lasted until late afternoon and my brother and I were sent off to a restaurant for lunch only to return after eating to slip in and out of the ongoing religious services. In previous years the men’s attire was probably as unusual as one would see anywhere. Many men wore top hats, morning coats and striped pants, and on the lapel of their morning coats they proudly displayed their German World War I medals. This, they thought, marked them as good Germans. They looked as if they were presenting their credentials to God and requesting another year of accreditation. The synagogue had an excellent choir and a very harmonious organ that played during the service. The reverberations and echo were so well tuned that the synagogue was sometimes used for choral performances. The cantor had a most resonant voice and could easily have qualified as an opera singer.”

Rosh Hashanah under Nazi Surveillance

During the Holocaust, the Nazis sometimes chose the High Holidays as a time to humiliate and inflict more suffering on the Jewish community. This was the case for the Jews in Dukla, Poland, who soon after the German occupation of their country in September 1939, celebrated Rosh Hashanah under Nazi surveillance. In his memoir, The Vale of Tears, Rabbi Pinchas Hirschprung describes the ceremony and his community’s commitment to maintain its faith and culture despite persecutions.

“On the eve of Rosh Hashanah, with prayer books in their hands, fear in their hearts and reverence for God on their faces, men, women and children poured into the synagogue.

Never before in Dukla had it felt so much like the Days of Awe* were upon us as it did that evening. The holiness of the Day of Judgment* had placed its seal on the town. Heads lowered, with measured steps, the Jews quietly and calmly shuffled by while Nazi soldiers with cameras photographed “the Jewish procession.”

...

Unofficial rumours were circulating that Warsaw had already fallen. Of course this piece of news heightened the significance of the Day of Judgment. Our fear kept growing and growing and growing.

In the morning, the synagogue was again full of people with ‘instill Your awe’ clearly visible in everyone’s face. We had completed the morning service and had begun preparing for the blowing of the shofar. First, we sent out a ‘reconnaissance party’ whose task it was to ascertain whether the ‘voice of the shofar’ could reach the ears of the enemy. After that we sealed the synagogue gates and then we sounded all one hundred blasts at the same time, furtively and hurriedly, ‘in a single breath.’ Although the sounds were quiet, they nevertheless produced a strange apprehension, and the stillness in the synagogue resembled that of a cemetery.

Having carried out our covert operation, we threw open the gates before beginning the additional prayer service. The cantor recited the Shemoneh Esrei* with passionate fervour and profound sensitivity. The words of the prayer that the cantor sang so sweetly gave such pleasure to those praying that everyone felt refreshed and renewed. Feelings of degradation and dejection dissipated, and the congregation was infused with feelings of exaltation and spiritual elevation.

These feelings, however, did not last long. Nazi soldiers arrived to destroy the fragile calm and delicate tranquility that had so tenderly soothed us.

The cantor, transported into the ‘higher realms’ of prayer, had not a clue as to what was happening behind his back. He continued praying with the same passion, but the congregation had become distraught and alarmed. Our first thought was that this visit from the Nazi ‘guests’ was due to the blowing of the shofar. But this suspicion vanished after the Nazi visitors ordered us to carry on quietly with our ‘ceremony.’ They were evidently curious to observe the service. For a few minutes they remained seated in the seats that some members of the congregation had offered them. Then a few of the Nazis got up from their places, set up their photographic equipment and photographed the congregation. When they were finished photographing those praying, they photographed the cantor, who was completely indifferent and carried on with his prayers as though the whole matter had nothing to do with him.

Afterward they went over to the Holy Ark and gave one member of the congregation the ‘honour’ of opening the Ark so that they could photograph the Torah scrolls housed inside. Having completed their work, they left and everyone took a deep breath.”

*Days of Awe Also known as Ten Days of Repentance, this is another term for the first ten days of the Jewish year, beginning with Rosh Hashanah and ending with Yom Kippur — a time of reflection, repentance, prayer and forgiveness.

*Shemoneh Esrei The Jewish prayer that is recited three times daily while standing and facing Jerusalem.

*Day of Judgment Another name for Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, referring to it as the time when humankind undergoes Divine judgement.

First Rosh Hashanah in Canada

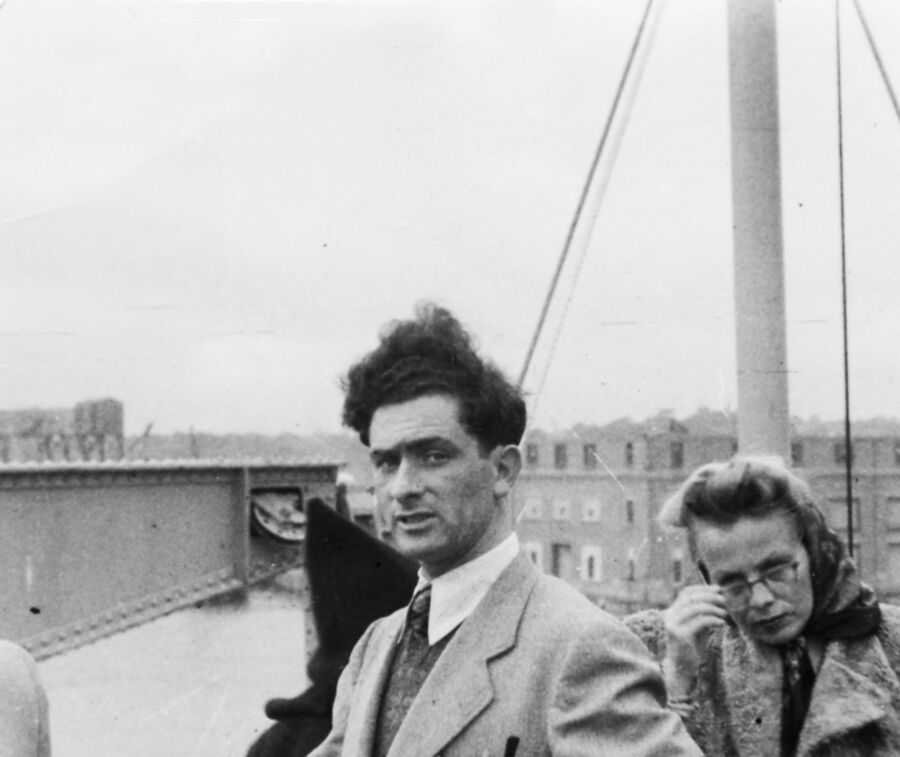

The eldest of seven children, Willie Sterner was the only one of his siblings to survive the Holocaust. After the war, he lived in displaced persons camps in Austria, and in 1948, he and his wife, Eva, immigrated to Canada. In his memoir, The Shadows Behind Me, he describes his first celebration of Rosh Hashanah in Halifax, the day after his arrival in his new country. Greeted by people from the local Jewish community, Willie reconnects with the family spirit of this holiday and finds joy in discovering the cultural differences of the traditions at the synagogue in Canada. The holiday becomes a way for Willie to learn about his new home.

“When our ship docked in Halifax, it was the eve of the Jewish New Year — Rosh Hashanah — and some people from the local Jewish community came aboard to ask if we would like to stay in the city over the High Holidays so we wouldn’t have to travel by train to Montreal during the holiday. Some of our people, including my wife and I, decided to accept that generous invitation. The Jewish people in Halifax were very friendly and spoke to us in Yiddish, so we felt at home. They took all of us from the port to a nice hotel.

The next day was Rosh Hashanah. In the morning, a Jewish man from the Halifax community came to our hotel to tell us that he would take us to a synagogue for the holiday services. We got into cars that were waiting outside the hotel and drove to a modern synagogue. The service was a little different from the services in our former country, but it was nice and the cantor was very good. Rosh Hashanah in Halifax was the first real holiday we’d had since we had been separated from our loved ones in 1942. The holiday was also special because it was our first Rosh Hashanah in Canada.

After the service, we were taken to visit Jewish families in Halifax. Our group — the Shnitzer family and my wife and I — visited the home of the Zemel family. The Zemels gave us a warm welcome and we felt at home with them. They were very friendly. Because Eva and I hadn’t been to a Jewish family holiday for so many years, we felt that we were members of their family. Mrs. Zemel placed all of us at a large table in the dining room. Eva stood up at her place and asked Mrs. Zemel if she could be of any help. Mrs. Zemel and all her guests were pleasantly surprised. Mrs. Zemel took Eva into the kitchen and they came out with delicious, traditional food prepared especially for Rosh Hashanah. I was so very proud of Eva — she was a great help to Mrs. Zemel and was appreciated by our hosts and their guests.

Eva and I were glad that we had stayed with such warm people in Halifax, but after the lovely holiday it was time to continue on to Montreal. It was hard saying goodbye to the Zemels because we already felt so close to them. They asked us to stay in Halifax — they said that they had a small Jewish community and that we would be happy there. But our destination was a transit camp in Montreal and then Toronto, where we had been assigned to go. Eva and I will always gratefully remember the warm welcome we got from the Zemel family and the whole Jewish community in Halifax.”