Un si grand péril

Eva Lang

Trois étoiles dans le ciel

Les maisons d’enfants étant devenues la cible des autorités de Vichy, l’OSE avait décidé d’avoir recours à un moyen plus radical de cacher les enfants juifs français : il fallait changer leur identité, leur faire accepter – même si c’était incompréhensible pour eux – qu’il leur faudrait prétendre être quelqu’un d’autre jusqu’à la fin de la guerre. Nous étions des petites filles, mais on nous demandait de nous comporter comme des adultes. Nous devions jouer double jeu, adopter complètement cette nouvelle personnalité et nous conduire normalement malgré tout. Les responsables de l’OSE nous ont fait promettre de ne jamais révéler nos vraies identités, et je n’ai jamais eu vent de qui que ce soit qui l’ait fait par inadvertance, même si notre petit groupe comptait des enfants de 5 ans à peine.

J’aimerais pouvoir rencontrer les quelques merveilleux administrateurs qui ont eu cette idée géniale de cacher des enfants juifs dans les maisons d’enfants du gouvernement, administrées par le programme Entr’aide d’hiver du Maréchal. La vie dans ces maisons n’a toutefois pas été simple. Quelques-unes de mes amies m’ont raconté, après la guerre, y avoir été très malheureuses. Par ailleurs, un certain nombre d’enfants n’ont pas bénéficié de ces cachettes. Des filles ont été exfiltrées en Suisse, certaines sont devenues bonnes à tout faire dans des maisons privées, d’autres ont été envoyées dans des couvents ou des fermes. Grâce à quelques braves gens, des enfants innocents ont ainsi pu être sauvés des griffes allemandes.

Un soir, chef Cabri m’a dit : « À partir de demain matin, à l’aube, tu t’appelleras Yvonne Drapier et ta sœur, Raymonde Drapier. Vous ferez partie d’un petit groupe de grandes, avec des petites sœurs que vous protègerez tout le temps. Et maintenant ceci est la courte histoire de ta famille : ton père est né à Ménilmontant, il buvait beaucoup et ne se souvenait de rien. Il a été appelé sous les drapeaux et fait prisonnier en Allemagne. Ta mère, tout le monde ignore où elle se trouve. Après qu’elle vous a quittées, ta sœur et toi, vous avez été trouvées dans la rue et placées dans les maisons d’enfants du gouvernement. Si on ne vous demande rien, ne dites rien, absolument rien, et essayez de ne pas vous faire remarquer. »

David Korn

Sauvés par la chance et le dévouement

Nous avons quitté Spišská Stará Ves à la faveur de la nuit pour nous réfugier dans une ferme située dans un village voisin. Nous passions nos journées dans la maison de notre hôte et n’étions autorisés à sortir qu’au crépuscule, quand nous étions certains que ne nous courions aucun risque d’être vus et trahis. Au bout d’un mois environ, le fermier a expliqué à mes parents qu’il était devenu trop dangereux pour lui de nous cacher, car héberger des Juifs était passible d’une condamnation à mort. Nous avons donc dû partir.

Nous avions tout de même eu de la chance de quitter le village de mon père au moment où nous l’avions fait. Le 26 mai 1942, tous les Juifs se trouvant encore dans le secteur avaient reçu l’ordre de la police locale de se rendre à la synagogue. Avec le concours zélé de la garde Hlinka, hommes, femmes, enfants et personnes âgées avaient été arrêtés et déportés dans un camp nazi de mise à mort.

Lorsque nous avons quitté la ferme, mes parents nous ont emmenés dans la ville voisine de Stará Ľubovňa, où vivait ma tante Malka et où était né son mari, Joseph Taub. Ils s’étaient mariés en 1941, lors d’une cérémonie dont je me souviens encore très bien, même si je n’avais que 4 ans à l’époque.

Par l’intermédiaire des Taub, chez qui nous sommes restés un certain temps, nous avons pris contact avec un pasteur local, prêt à aider les Juifs. Ce pasteur évangélique luthérien nous a fourni, à mon frère et moi, de faux papiers d’identité selon lesquels nous étions des chrétiens nés dans un village non loin de Stará Ľubovňa : Jacob s’appellerait Kubo, et moi, Šano Alexander. Après avoir reçu ces documents, je me rappelle avoir lu « Juifs et chiens interdits » sur un panneau à l’entrée d’un jardin et m’être alors dit : « Maintenant, nous pourrons y entrer. » J’avais 5 ans.

Par la suite, le pasteur a contacté un orphelinat dirigé par les évangéliques luthériens à Liptovský Svätý Mikuláš, une ville située à une centaine de kilomètres d’où nous nous trouvions. Quand nous y sommes arrivés le 2 octobre 1942, mes parents ont demandé à Vladimir Kuna, le pasteur qui dirigeait l’orphelinat, de recueillir leurs deux enfants juifs et de veiller sur ces derniers jusqu’à la fin de la guerre. Si quelque chose arrivait aux deux parents et qu’ils ne s’en sortaient pas, leurs enfants, quant à eux, survivraient. Rester ensemble voulait dire courir le risque de tous mourir. Rétrospectivement, même si cela a dû être un véritable déchirement pour mes parents, leur décision de se séparer de nous s’est avérée la plus sensée, la meilleure. Ils ont été clairvoyants, et le hasard a joué en notre faveur.

Fishel Philip Goldig

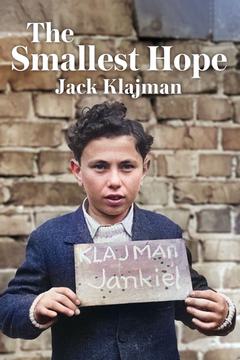

Le récit de survie d’un jeune garçon

Les premiers temps, nous nous cachions dans le grenier de la maison du fermier. Cela s’est toutefois avéré dangereux, car les enfants, qui ignoraient alors que nous étions là, y montaient parfois pour chercher des jouets ou pour s’amuser. Certains enfants du voisinage venaient souvent aussi, surtout en hiver. Et si ne serait-ce qu’une personne avait révélé notre présence, nous serions tous morts. Nous devions donc trouver un autre endroit où nous cacher.

La cour de Nikolai et Yulia Kravchuk s’étendait jusqu’à une petite colline, dans laquelle, des années avant notre arrivée, le fermier avait creusé un abri qui ressemblait à une grotte, avec des murs et un plafond de pierre. Il y stockait ses réserves de pommes de terre pendant l’hiver.

Nous pensions pouvoir nous cacher dans cette grotte, mais, hélas, les habitants des environs allaient et venaient pour acheter les pommes de terre du fermier, et nous craignions que les enfants, qui jouaient à proximité, nous entendent. Un jour, à la faveur de la nuit, mon père, mon oncle et le fermier ont déplacé quelques grosses pierres situées au pied du mur de la grotte et ont creusé davantage dans le flanc du coteau pour créer un abri où nous pourrions nous dissimuler. L’ouverture de la grotte, petite et étroite, était juste assez large pour nous permettre d’y entrer en rampant. Par la suite, nous l’avons élargie, rallongée et rehaussée pour pouvoir tous nous y cacher : mes parents et moi, ma tante et mon oncle, et Eva, ma cousine de 3 ans. Une fois à l’intérieur, nous remettions les pierres à leur place de telle façon que personne ne pouvait rien détecter en entrant dans l’espace où étaient stockées les pommes de terre.

La grotte n’étant pas très haute, je devais baisser la tête dès que je me levais. Il y faisait chaud et sombre, aussi disposions-nous de lampes à pétrole et de quelques bougies pour nous éclairer. Un grillage recouvrait la fenêtre insérée dans la porte d’accès à la grotte, ce qui nous permettait de respirer. Kravchuk nous a donné une petite table, des couvertures à disposer sur le sol et pour nous couvrir, ainsi que de vieux vêtements qui avaient appartenu à ses enfants.

Une fois par jour, tôt le matin, il nous apportait de quoi manger et récupérait les déchets. Il nous amenait également un grand pichet d’eau pour faire notre toilette et boire. Parfois, il prenait le temps de discuter. C’était un homme sympathique et agréable, même si sa femme et lui avaient peur de nous cacher. Ils hésitaient souvent à venir dans notre trou, car ils craignaient que des voisins les voient. Ils vivaient dans la peur constante d’être trahis.