Tova Himelfarb

Born: Sochaczew, Poland, 1928

Wartime experience: Ghettos, hiding

Writing partner: Dora Usher

Tova Himelfarb (née Chaya Tauba Tykochyner) was born in Sochaczew, Poland, in 1928. When World War II started, her father was conscripted into the Polish army but returned to his family within two months.

Tova and her family were forced first into the Sochaczew ghetto and then into the Warsaw ghetto, where they remained for a year and a half. After escaping the ghetto and spending time hiding on farms, Tova separated from her family in the hope of being able to survive more easily. Tova ended up working on a farm called Gelinova, near Sochaczew, from 1942 until six months after the war ended. Her parents, brother and one of her two sisters were killed during the war. Tova and her surviving sister, Yehudit, reunited and in 1945 went with Aliyah Bet to British Mandate Palestine. In Haifa, Tova worked as a children’s nurse at a hospital. She immigrated to Canada in 1960 with her husband, Ephraim Yitzchak (Jack), who had survived the war in the Soviet Union, and their two children. Tova Himelfarb passed away in 2016.

Life was Simple

When I was a child, we lived in Sochaczew, in Sochaczew County, Poland, in an apartment building with three floors. Our address was Staszica 28. Sochaczew is a town about fifty kilometres west of Warsaw, between Lodz and Warsaw. Buses were always passing through our town to Lodz. I remember running to see the buses, to see their wheels turning, because that was a novelty for us.

Our life was difficult, but it was nice. We were four children, three girls and one boy. The eldest was a son named Aba. I was child number two, but I understand there was a child before me, Chavie, who passed away from diphtheria. Then there was Yehudit, but they called her Yiskale, after my grandfather, Joseph Berkovichi, who had passed away. I never knew him. When my sister was born, she was named after him, but now she is Yehudit, living in Israel. Then another baby was born, named Sara, who was the last child.

My father made leather goods for horses. Today we have cars, but then transportation was by horse and cart, so drivers needed things like bridles and reins to drive their horses. I remember that my mother would sell some of these items at the market to earn a little more money. It was a small business, but it seemed to provide enough; on Friday night we always had a nice dinner.

My grandmother, Molly Berkovichi, also lived with us because my grandfather had passed away. She stayed with us until the end, until the Germans came.

We had a very nice home. I never remember my father and mother fighting or having an argument. None whatsoever. And I always thought, is it my imagination? Did they argue behind our backs or was it really the truth? I believe it was a good marriage.

We lived in two rooms. There was a little sofa for my brother, and the rest of us all ended up in two big beds with our parents because that is all the space we had. So it was not luxurious. But very few people had luxury at that time, that’s for sure.

When I turned seven, I went to a Christian public school, but in the evening we went to a Jewish school, a Beit Yaakov, a school for girls, for a few hours. I still remember a song, “V’ahavta l’rei’acha,” which means “You should love your friend,” and contains the words “Zeh klal gadol, gadol baTorah,” a phrase that means “this is an important principle in Torah.” I still remember that. Yes, I knew a little bit of Hebrew, even then.

Our home was kosher. I wouldn’t say it was 100 per cent kosher, but it was kosher. My family was very involved in taking care of us. We were not overly religious, but my father went to the synagogue every Saturday. Life was simple, every day more or less the same — the milkman would come with milk, we would get milk and a bun for breakfast, and we would go to school. That was the normal routine.

So life was okay. It was a normal life. And then things changed.

In Poland, including the area where we lived, there was a lot of antisemitism. At Easter or at other holidays, all the Jews tried to keep away from the churches. A priest used to come to the school to preach about Christianity and the Jewish children were asked to leave. There were many things like that between us. But I also remember playing with Christian children because we lived in an apartment building and there were Christians living beside us. At Passover we usually got nice new clothes and new shoes, and they were jealous; they would look at us and try to damage our nice clothes because they hated us. Stuff like that would happen.

Otherwise life just went on. That is, until the Nazis came.

I could not tell them that I was Jewish or they would kill me, too.

Like Little Birds

As soon as the Germans came, the Polish government mobilized people. Our father was conscripted into the Polish army in 1939. I remember going to the railway station to say goodbye; we were all crying. Who knew whether we would see him again? My mother was left alone with four children, and my grandmother was with us, too.

We tried to run away from Sochaczew, which was fairly large, to a smaller town in the district, where we thought we’d be safer. We were afraid that Sochaczew would be bombed. So we went to the smaller town and lived there from the time we knew the Nazis were coming to the time that they arrived. My brother was left behind because he could not go to school anymore; it was the end of schooling. He was placed at a barber’s shop, learning to cut hair. I was sent to a woman who could teach me sewing.

It didn’t take very long for the Nazis to arrive in that small town. I remember what happened. I saw people being caught, being rounded up and taken away; I don’t know where, but they were probably taken to camps. I saw large groups of people walking, and we always went out looking for my father but we couldn’t find him. Maybe a month or two after the Nazis had arrived, we returned to our house in Sochaczew. After that, I remember the Nazis really going after us. They would come in and complain that everything was dirty. We’d been away for a long time, so it probably wasn’t that clean, and they made us clean the house. They would drag people into the street at night, at two or three o’clock in the morning, and beat them up. We could hear the screaming, and it terrified us. Everyone was afraid to go outside, to do anything. We were so frightened of the Germans. Those were terrible times.

***

My mother and father looked at the situation in the Warsaw ghetto. There was no money; there was no space; there were no clothes. They started to sell everything they had to put a little bit of food on the table for the children. Slowly but surely everything went; nothing was left. We had relatives in the United States and used to get parcels from there before the war, with a little jewellery and some nice clothes, but everything was sold. So my mother and my father decided we had to get out of the ghetto because once everything was sold, we would die there. My father and my brother went out to look for a place where we could hide, and we didn’t hear anything from them. My mother was left with my two sisters, Sara and Yehudit, and me. After a while she decided she had to find my father. She thought that the people we dealt with, who were nice people, would perhaps hide us. We used to give them credit in the little business that we had. They knew us and where we lived. She had an idea of where she might find my father, but we had no way to communicate with him. We were not allowed to have a radio, not a newspaper, nothing. So my mother told me she had to leave but would be back soon, and I had to look after the two other little children.

Sara was maybe three or four, and Yehudit maybe five or six. We were left in that room with no money, with nothing. I tried to feed them, but how? I sold everything we still had, even underwear; we sold everything for pennies in order to get a little bottle of oil, a little bread, potatoes, something to feed them with. That’s what I did. There was no other choice. It seemed to go on for a long time, but I cannot tell how long it was. I cannot tell, but I know it was a rough, rough time.

One time we were rounded up and we ended up in a basement. I don’t know why we were there. We were on the street and were picked up and put in this basement. From there on, my memory is not good, but I know we got out of there. I really don’t have any memories any more of what happened in that place. But we got out of the basement and were still walking the streets. If I could scramble together a little bit of money for food, I would buy one of the pancakes that people sold on the street, and we would share the pancake. I remember taking the children to a place where there was a soup kitchen. There was soup with a little barley, a few bits of carrots, and the three of us would have some food. We always went back to sleep in the same place.

***

After we left Warsaw, we kept on walking. We walked slowly. I remember that my mother would sometimes take us to a farm. She had arranged with people to hide us; maybe they got paid, as my mother had some jewellery to give them as payment. Some farmers would take us in for a short time, some would turn us away. They could have killed us or they could have raped us; they could have done anything they wanted with us. Sometimes we ended up in a barn where they kept the cows. At least it was warm. Or they kept us in the stables, where the horses were. If we were lucky, we got a little bit of food. My mother would do some work for them. I cannot say what exactly; perhaps my mother was hiding horror stories from us.

We came to one farm where they let us stay for a period of time. My mother started to work a little bit and get food in exchange for her work. She started to feed us, but the food would not stay in because we could not absorb food anymore. It was going in and coming out. We were very skinny; we probably were close to the end of our lives. If she hadn’t come back when she did, we would have died. So we ended up on these little pots, sitting there. She would feed us like little birds, little by little, some porridge, to bring us back to life. After a while, the farmers told us to keep going, that we had to leave.

Alone

From that place my mother took me to another farm. I was only twelve, maybe thirteen, then. She took me to a place called Gelinova, a farm very close to Sochaczew, only about five kilometres away. I lived on that farm for more than three years. My sister was still alive, so I know that I went there in 1942, and the war was over in 1945. I stayed on the farm for another half a year after the war because I thought no Jews were left, because nobody came back to find me.

I stayed where I was, in Gelinova. The war was over and the Soviets came in on January 17, 1945. That date is in my memory. I sometimes forget my grandchildren’s birthdays, but I still remember that day.

The farm where I lived had a big house, and at that time the woman who owned the farm also had a woman helper from Warsaw. There was a lot of turmoil in Poland because the Soviets were coming in from one side and the British from the other. And the helper had come from Warsaw because they were bombing the city. The helper and I shared a room upstairs, at the top of the house, where we slept. When the Soviets arrived, they took over the kitchen. You didn’t argue with them. What they wanted, you gave them. The kitchen was on the ground floor, and there were stairs going up to the bedroom that we shared. The two of us were upstairs.

The helper was much older; I was still a young girl. All of a sudden, I saw a light coming up the stairs. I got so scared because I knew what happened when the Soviets, or anybody, came in at that time during the war. They got away with rape. I was terrified. I didn’t know what to do. I was really scared. I first went under the bed. Then I somehow ended up sneaking out. They grabbed hold of the other woman and all was quiet. I never heard what was happening. I know she was alive, so obviously they raped her. I went downstairs where the owner was while they were doing that. I was so afraid. I was very small. They probably would have damaged me a lot.

The Soviets stayed for two or three weeks. After they left, I thought, okay, the Nazis are gone, the Soviets are gone, and I am alone. They think I’m Christian. I could not tell them that I was Jewish or they would kill me, too. It was dangerous, the way I heard them talking. But the woman who hired me, who lived in Warsaw, she understood the whole thing. She was very intelligent, although she was not educated. One day her brother came from Sochaczew and started to tell her husband, “The bloody Jews, they’re just like vermin, like nits. You can’t get rid of them. A Jewish family has survived.” That’s all I had to know — that one family had survived, that someone Jewish was still alive. The brother had said there was a whole family that was Jewish. In my mind, I had believed that there were no Jews left. The whole thing was so horrible; no one could possibly have survived.

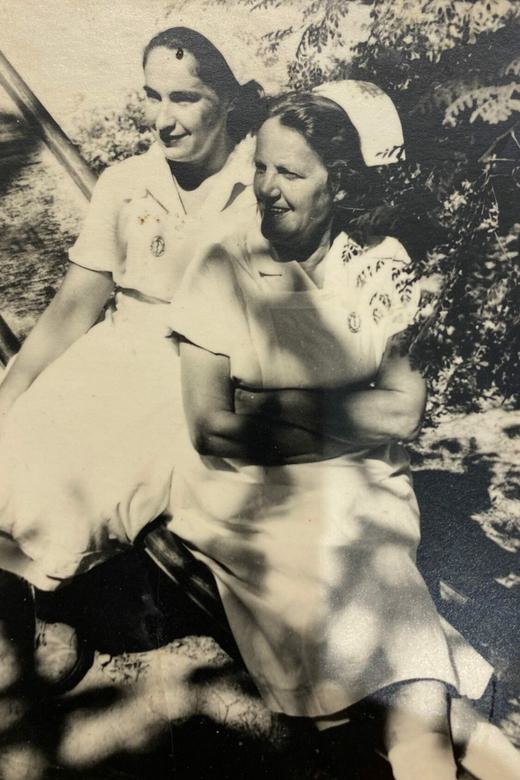

Tova (left), in her nurse uniform. Haifa, Israel, circa 1954.

Tova (standing second from the right) at Kibbutz Ginosar. Israel, circa 1948.

Tova and her husband, Yitzchak (Jack) Himelfarb, on their wedding day. Israel, circa 1953.

The Only Ones Left

I now knew that my sister was alive and I knew that I had to go to that rented place where they could help me find my sister. I went to talk to the woman, which was dangerous. I explained what happened and that I was Yehudit’s sister. She said she would never let her go unless with a blood relative. “You’re a blood relative, so I will let her go if she wants to go.” She had resisted that with all her might. I slept with Yehudit overnight. I said to her, “Yehudit, we are the only ones left, we don’t have anyone else. Why don’t you come with me? I believe we can reach Palestine. We can still go to school — you are still young — and we can still have a life. We can both still have a life. Why would you want to stay here and be on a farm with the cows? This is not our life; we are not used to it. It’s not our way of living.” I talked to her the whole night. In the morning she said, “Okay, I will go with you.” We decided that we would meet at the place where the few Jewish people were gathering. It was not too far. I don’t know how she got there, whether she got a ride on a bike; I don’t know and I never asked her.

In Warsaw, we met other Jews who came from hiding in the forests, from the Soviet Union, from the countryside. We were always on guard from the Poles. Aliyah Bet was organizing our journey to Palestine. It was a complicated journey. We went through forests and paid people at the borders. We went through Prague and Greece to Paris and eventually to Marseilles. From there we went by boat to Cyprus, where we were in a camp with guards around us. It was like a jail.

We finally reached Palestine, and it was still 1945. I was seventeen years old. I arrived in the Land of Israel before Israel was born. I ended up on Kibbutz Ginosar.

Israel did something for us that nowhere else could ever have done. It gave us a spine to be ourselves, a spine to feel like human beings again. And I think that Israel has a lot to do with all those survivors. They survived and they had children, beautiful children.

And that is what happened to us.