Lea Hochman

Born: Pohorce, Poland (now Pohirtsi, Ukraine), 1921

Wartime experience: Passing/false identity

Writing partner: Marilyn Targonsky

Lea Hochman (née Zimmerman) was born in the village of Pohorce, Poland (now Pohirtsi, Ukraine), in 1921. Lea grew up in an observant family with four siblings.

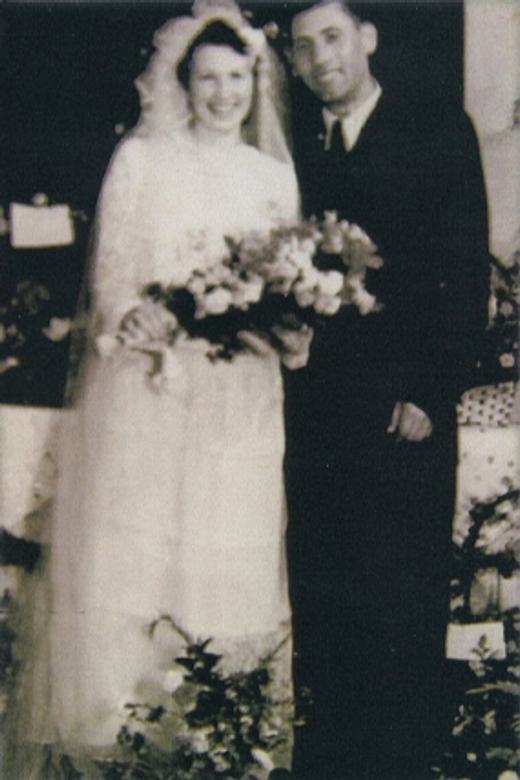

In 1939, after the onset of the war, the area Lea lived in came under Soviet occupation. After the German occupation in 1941, the nine Jewish families in Pohorce were targeted and eventually sent to a ghetto in the nearby city of Komarno. Lea escaped and lived in disguise and on the run for the rest of the war, passing as a gentile. After the war, Lea reunited with her two surviving siblings. She eventually left Poland and lived in displaced persons camps in Germany where she met her future husband, Avraham. They moved to Israel in 1949 and to Canada in 1959, settling in Montreal, where Lea reunited with her two brothers. Lea and Avraham raised a family and Lea worked in the garment industry and then became a dressmaker. In 1990, after her husband passed away, Lea moved to Toronto to be closer to her children and grandchildren. Lea Hochman passed away in 2021.

Life in the Village

After my parents married, they had five children together. The eldest was my brother Avraham, followed by my sister, Raizel, my brother Yisroel, me and my youngest brother Zvi Ariye, whom we called Hersh. During World War I, my father had been a soldier. While he was away at war, my grandparents and my mother raised the three eldest children. Zvi Ariye and I were born after World War I.

My father inherited quite a few acres of farmland, and our livelihood came from farming the land. My father knew everything about farming. We grew four kinds of grain: rye, wheat, barley and oats. We also grew potatoes. Our largest crop was rye. Jewish girls were usually more pampered than I was; they would stay in the house to help their mothers. But I worked outside in the fields, the garden and the barn. In the summertime, we worked the hardest. During harvest time, I went to the fields, but instead of just watching the workers, I brought tools and worked alongside them. By the time I was sixteen, I had also learned how to feed and milk the cows, chop wood for the wood-burning stove, take care of the cattle and hold the horse’s reins in my hands. Growing up on a farm gave me the opportunity to learn almost everything related to farming and harvesting. Everything I learned at home and in the fields was very helpful to me during the war and contributed a great deal to my survival.

Our home had a kitchen, a small bedroom and a small storage room. The kitchen, in addition to being used for cooking and meals, served as a bedroom for my family. It was also where we would daven (pray) on Shabbat, Saturday Sabbath and yontif, Jewish holidays.

Times were very tough, not only for us but also for the other people in the village. We had no electricity, no running water, no heat in the winter and no air conditioning in the summer. With no electricity or running water, no sink in the kitchen and no indoor washroom, how do you manage? How do you do the dishes or laundry, or get up in the middle of the night and go outside, even during storms? How did we bathe? If you can picture that, you will know how and where I grew up. Many people wouldn’t believe what it was like. We didn’t have a telephone, a radio or a newspaper. We didn’t have a clock, only a small windup watch to tell us the time. Compared to today, life was quite primitive.

I learned three languages: Yiddish, Polish and Ukrainian. At home, we spoke only Yiddish — we were not permitted to speak anything else. At school, we spoke Polish and Ukrainian, and in the streets, we spoke only Ukrainian. By the time I was five years old, I was able to speak these languages fluently.

School presented many challenges for me. There was one school for everyone and we had to attend or we would be punished. There were four teachers, four classrooms and seven grades. None of the other Jewish families in the village had children my age. I was the only Jew in my grade for seven years, so I played with the Polish and Ukrainian children.

The teachers did their best to give us a lot of information and knowledge. Once a week, a priest came into the class to teach religion, which created a difficult situation for me. People in Poland were very religious. On Sundays, the men, women and children went to church. There was a big cross on the wall at school and the students had to say their prayers while facing the wall. I stuck out like a sore thumb; I didn’t know what to do. Should I sit, should I stand, should I do anything? My parents told me that I should leave the classroom when the priest was teaching, but that I had to be very careful. Once, the preacher came over to me and told me to sit down and listen to how he taught the children. I was shaking and wondering what he was going to do with me. I was a young child and I had no idea what was going to happen.

Once a year, the priest told the class that on New Year’s Eve, he would teach about the Old Testament. The preacher told me that he knew the aleph-bet, Hebrew alphabet, because he’d had to learn many things before he became a preacher. I am not sure, but I believe that he shared this information to make me feel more at ease.

Escape from the Ghetto

One night in November 1942, sometime after midnight, our house was surrounded by Ukrainian police. We were dragged out of our beds. My mother was able to push my brother Hersh out the window. The building that we had used for our dairy was located about five feet from the house. Hersh climbed a ladder and hid in the attic of that building.

They took my father, Yisroel, and me. My mother had broken her hip before the war and was left behind because she limped and walked very slowly. They didn’t wait for her because they were in a hurry to gather up the other eight Jewish families in our village. My mother went to the dairy building, got Hersh and took him to Nestor’s barn. She convinced Nestor to hide him for a couple of days. In the meantime, she went back to the dairy and climbed up the ladder and hid in the same space that Hersh had used. It was freezing cold, so she found a sheet that was left over from the summer and used it to cover herself as best she could.

All nine Jewish families, including my father, Yisroel, and me, were taken to the police station in the village and locked up. In the morning, they took us by horse and buggy to the ghetto in the city of Komarno. There were signs everywhere, on walls and on trees, warning the gentiles that if they hid or saved any Jew, they would be killed together with the Jew.

In the morning, my mother climbed down the ladder. She couldn’t carry the sheet on the ladder so she threw it down before she began her descent. The neighbour who lived closest to us was named Irena. My mother had shared our food with her when she was under threat of starvation. Irena grabbed the sheet while my mother was still on the ladder. She said, “Sarah, you are going to die anyway and the sheet will come in handy for me.” She called the police and they sent a horse and buggy to bring my mother to the ghetto in Komarno. My mother had to ride in an open cart for twelve kilometres to the Komarno ghetto, wearing only the clothes that she had been sleeping in. There were now four of us in the ghetto. Hersh was still hiding in Nestor’s barn.

We were taken to a little room where there were eighteen people and no furniture. It had been chopped up for firewood. There was not enough room for all of us to sit on the floor so my parents and I climbed a ladder to an open attic. My mother took me in her arms to combine our body heat in an effort to stay warm.

That night, I had a terrible nightmare. I dreamed that I had been shot by a Ukrainian policeman. I felt the bullet in my chest and felt the blood running down my back, and I knew I was dying. I was waiting for my neshama, my soul, to leave my body. I must have made a noise because my mother woke me up to shush me as everyone was sleeping. I felt a tremendous amount of fear. I was shaking like a leaf. I kept repeating over and over, “I have to run.” I didn’t ask any questions. It was not logical but I felt that I had no choice but to flee. I left both of my parents in the attic. I climbed down and found my brother Yisroel. I said, “Can’t you see that I am dying? Take me out, take me out! I can’t stay here!” Yisroel thought that I had lost my mind.

We used to call Yisroel the investigator. He was always checking out his surroundings to look for ways to accomplish things. He knew that the ghetto was made up of four streets surrounded by barbed wire on three sides. The fourth side was bordered by a very wide and deep creek. I don’t remember how we got to the other side. Perhaps there was a fallen tree that we used to cross over. Yisroel had figured out a way. When we left, it was pitch-dark. It was fifteen to twenty minutes between my dream and our crossing to the other side of the creek. As soon as we reached the other side, hell broke out on the ghetto side. All of a sudden, there were a lot of lights. We heard screams, babies crying, the barking of German dogs and then we heard shots being fired. We began running.

I picked the name Eva, which is the Ukrainian version of Eve. I did not want to have a real gentile name and Eve was the first woman Hashem created. We had always communicated in Yiddish. We now had to speak only in Ukrainian.

Becoming Eva

We thought our chances of survival would be greater if we were not in a group, so we split up. My brothers went one way and Malka and I went the other way. Can you imagine how hard it was to say goodbye? My brothers were my last link to my whole family. Avraham was dead and we were fairly certain that my parents had already been killed as well. My sister and her family were in the ghetto in Rudky and we had no way of knowing if they were still alive. There was no radio, no newspaper and no communication except for word of mouth from the gentiles. I will leave our goodbye to your imagination.

It was late in the evening, it was drizzling and Malka and I were dressed in skimpy clothing. We had no place to go so we just walked. We saw a light in the distance and walked in that direction. Two brothers had built houses, side by side. There were no neighbours, and it was in the middle of nowhere. Malka had a pillowcase. They allowed us to stay the night in exchange for the pillowcase. In the morning, one of the brothers said that if we gave him a present every day, he would keep us safe. It so happened that Kasia Malachijka, Malka’s next-door neighbour, still had our belongings. She was keeping them on our behalf. It looked like for the time being we could live a little longer.

Esther Friezel and Ratzi Adler were two Jewish girls who had worked with my brothers and Malka at the German headquarters. They were taken to the ghetto in Rudky at 4:00 a.m. That evening, they were able to escape from the ghetto. While they were in the ghetto, they saw my brother-in-law Moshe Laizer, my sister Raizel’s husband. He told them to deliver an important message to me. His message was, “Tell Lea not to be a sitting duck. She is the only one in the family who can save herself. She speaks Ukrainian and Polish perfectly, and she can pass as a gentile. Tell her to dress like a gentile farmer’s daughter. She should try to be in groups when the Germans are checking for documents. Since she has no identification, she may be captured and sent to a forced labour camp where she has a chance of survival.” Forced labour was called Zwangsarbeit. Gentiles without documents were sent to Zwangsarbeit. Jews were not given that option; if they were captured, they were murdered.

The girls were able to find me and deliver Moshe Laizer’s message. I felt that Hashem had sent me another miracle. In the ghetto, filled with thousands of people, how did the girls and my brother-in-law find each other? And then how did the girls escape and find me?

Malka thought that Moshe Laizer had a good idea. She brought some material from Kasia Malachijka that had been part of my hope chest. I traded the material for a skirt and a serdak, a sleeveless, quilted jacket that was commonly worn by gentiles during the winter. The serdak had two pockets, which helped me keep my hands warm as I did not have gloves. I also got a kerchief and a medallion of the Virgin Mother and Child, and a little Ukrainian prayer book. Malka gave me her shawl to cover my sleeveless arms. Ratzi and Esther were also dressed like gentile girls. The three of us walked out in the middle of the day on our long journey into the unknown. We left Malka behind. Esther took the name Stefka and Ratzi became Maria. I picked the name Eva, which is the Ukrainian version of Eve. I did not want to have a real gentile name and Eve was the first woman Hashem created. We had always communicated in Yiddish. We now had to speak only in Ukrainian.

Epilogue

Baruch Hashem, thank God, I am well over ninety-five and still able to share my story. I am the only remaining survivor from the two ghettos of Komarno and Rudky and all the surrounding areas. One of the biggest miracles was that three of us from one family survived. We each had a small piece of blessed matzah from the rabbi of Rudky’s afikomen.

For a very long time I was unable to talk about my experiences related to the Holocaust. With the encouragement of my family, I began to speak to many groups, which included both children and adults. Elly Gotz, a survivor speaker at the Sarah and Chaim Neuberger Holocaust Education Centre (now the Toronto Holocaust Museum) in Toronto, was the first one to record my story on film. As a survivor, he understands the importance of sharing our experiences with the next generation.

I am also thankful to the Azrieli Foundation for sending Marilyn Targonsky to assist me in putting my memories on paper. My daughter Sheila and I were able to expand upon what Marilyn transcribed.

I am blessed with a great memory and have the ability to recall details. Words of appreciation from my audiences have encouraged me to continue sharing my story about “the miracles of Hashem.” After so many years, I understand the importance of recording my story of survival on paper. My experiences were different from many other survivors. I was not in concentration camps or forced labour camps, but I was imprisoned in many other ways. Every survivor experienced her or his own miracles in order to survive.

I want to leave a legacy for my children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and anyone else who is willing to hear about the miracles of Hashem. I believe that the Almighty, in his great mercy, kept my brothers and I alive to raise a new generation to carry on. This is the mission of the Jewish people.

I want everyone to understand that life does not always turn out the way you plan. Sometimes events turn out differently from what we expect or hope for. We can’t control or foresee the future as it is not in our hands. There is a Jewish expression that says, “Der mentsh trakht un Got lakht.” (Man plans and Hashem laughs.) Although we sometimes think we are in control, we should always remember that life is not in our hands, and we have to rely on help from Hashem.

I specifically wish to honour Kasia Zadorozna and her parents, and Tadeusz Trawinski, Nestor and Polny, all of whom played a role in my survival and that of my brothers.

When I finished public school at the age of thirteen, I learned everything possible about farming, housework, sewing and cooking. I could speak three languages. My motto was to do everything better than everybody else. “No” was never in my vocabulary. I learned skills I never expected to use but needed in ways that I could never have imagined. Please remember that everything comes from above and is always for our own good, even if we don’t see the good right away.

What happened more than seventy years ago is history. What is going to happen tomorrow is a mystery. Today, we have to hope for the best but always be prepared for the worst. Important lessons from this horrible, unimaginable time need to be studied and learned by generations to come. I believe that there is much to learn from my personal experiences.

My advice is to do your very best in everything you do. Learn all that you can. Keep your mind sharp. You never know what might be important to you in the future. With prayer, strong belief and determination, you can overcome any obstacles in your life. There is always a light at the end of the tunnel. Never lose your hope or courage.

My final message to you is that without prejudice and hatred, and with understanding and tolerance for humanity, there is enough room in this world for everybody to live in peace. If you have good fortune, you have an obligation to share with others who are less fortunate. Always remember to give to charity and do acts of kindness. Above all, remember to have faith; no matter how bad things look, we must always remember that everything comes from Hashem. My mother used to say, “Iz keynmol nisht du dus shlekht az es zol nisht aroys kimmen tzi gitten!” (There is never something that is so bad that it will not turn out to be good!)