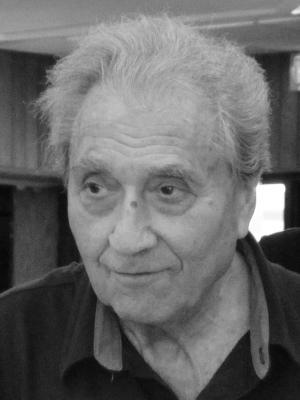

Tibor Feuerstein

Born: Fegyvernek, Hungary, 1931

Wartime experience: Ghetto and camps

Writing partner: Helena Adler

Tibor Feuerstein was born in Fegyvernek, Hungary, in 1931. Son of an Orthodox rabbi, Tibor grew up in a small town and had a good childhood, getting along with most of his neighbours. When Germany invaded Hungary in March 1944, the German SS used Tibor’s family’s house as their headquarters.

Tibor and his family were taken to a ghetto before being deported out of Hungary. He ended up doing forced labour on a farm in Ebergassing in Austria, narrowly avoiding deportation to Auschwitz. After five months, Tibor and his family were taken to Floridsdorf, a forced labour camp near Vienna, before being marched to Gusen and then to Gunskirchen, both subcamps of the Mauthausen concentration camp. Tibor was liberated by the American army on May 5, 1945. Tibor and his family returned to Hungary, eventually moving to Budapest, where he met and married Vera. Tibor and Vera immigrated to Canada in 1957, where they soon had their first child and started a wholesale business. Tibor Feuerstein passed away in 2015.

Deportation

I was a young boy experiencing a crazy life. My mother, Ava, Erzsi, Ernie, Imre, Iboyl, Erna and me were in the ghetto for about five weeks. Magda, Aliz and Béla weren’t home when they came for us, so they weren’t taken with us. Erna, the youngest child in my family, was only about six years old at that time. I was thirteen in 1944 and should have had a bar mitzvah that year, but I never did have one. One of my brothers remembers that we were next taken to the city of Szolnok, to a sugar factory. It was here that we first saw people being killed. There was a child crying in its mother’s arms, and a guard told her to put the child down. She refused and both she and the child were killed. We saw people lying in the mud, dying.

I don’t really remember exactly how I found out that we were going to be moved. No one told us anything except that we would be taken somewhere and that we could bring a few things with us. We all took everything with us, clothes we wanted to wear, a little food. I took everything I thought I’d need. My mother didn’t know what to take so she packed some flour and salt. We ended up eating spoonfuls of flour and salt when there was no other food.

We were taken away during the day; a truck came and picked us up. They put as many people as they could fit in the back of the truck, maybe twenty people, my family and others — girls and boys, mothers and fathers. We didn’t know the people who came to take us away, had never seen them before. The Germans did everything quietly. I don’t think the Germans let anyone know what they were doing. Only we knew what was happening to us. No one tried to stop them.

My family ended up in Austria. The journey there was terrible. We had to stand in a train for three days, the door locked, and there was no fresh air. When we got to Austria, the door was finally opened. The train had stopped at Strasshof an der Nordbahn, and Hungarian Jews who passed through Strasshof were then sent to different places to work. I think that all the other Jews from Fegyvernek were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau and were killed except for two families, the Epsteins and mine. We were sent to Ebergassing, a town in Austria, by tractor and wagon.

Although my family was taken together to Austria, we were separated for a time once we got there. I felt awful. My memories of that time are not clear. I remember that it took about five hours to get there; Fegyvernek is not far from Austria. We got very little to eat and drink, and this was when we first started to lose weight.

For the time we were in Austria, life was terrible. People who were able to work were used for forced labour. Later, if someone was no longer needed for the work, they were sent to the Nazi concentration camps.

I wanted to survive. I wanted to live healthy and free. I was afraid, but I figured I wouldn’t let anyone kill me. I was very skinny when I was in Austria, I can’t even explain how thin I was. They didn’t give us enough food, but I was strong.

Forced Labour and Liberation

We worked on the Baroness’s farm around Ebergassing, and in that general area, for about five months. When there wasn’t any more work for us to do in Ebergassing, the Germans came for us. We didn’t get any payment or anything for the work we did. They told me to get in the truck with my family; Ernie was taken to another work camp. I didn’t know where they were taking us. We never knew where we were going and didn’t know if we would survive — we saw what they had done to other people.

We were taken to Floridsdorf in Vienna, which was a subcamp of Mauthausen, housed in a school building. Imre remembers us walking there, but I think we went by truck. My mother worked for the Siemens factory and Imre and I cleaned rubble from the bombings. Imre remembers that one time when we came back at night we heard the air-raid sirens and one of the SS chased us and took us to the shelter in the school. There was a Jewish man in charge of the shelter and the SS guy told him to punish us, so he hit us and locked us in the basement. I got out before they came to let us out and Imre almost got out too. Later, this man apologized to my mother and explained that he had to hit us because the SS guy was there.

Then, we had to walk for almost two weeks to get to the Gusen concentration camp. We were in one of the last groups; each group had about one hundred people. By the time we got to Gusen, at least one hundred people on the forced march had died. Anyone who couldn’t walk had been killed. Young children who sat down on the ground when they couldn’t walk were shot.

When my family gets together now, we reminisce about how I got the nickname my family gave me, gonif, which means thief in Yiddish; along the way I took any opportunity to get whatever food I could to keep my family alive, taking it wherever I could find it.

At Gusen, people were told they were going to work but instead they were taken to the gas chamber. Every day, people were taken to the gas chambers. A woman recognized my mother when we got to Gusen and told her that her son was here; she took her to Ernie. Once again, the seven of us children were together with our mother, although I don’t think my family was kept together. Men, women and children lived separately. I don’t even remember if I slept in the same place as my brothers; we slept when we could. We had arrived at night at Gusen, and my brother remembers we were told to lie down on the ground to sleep and that tomorrow everything would be all right.

Soon, we walked from Gusen to Gunskirchen, another work camp. There were dead bodies everywhere. Whenever I saw people being killed, I tried to avoid the killers by being far away from them. I didn’t avoid specific people – every guard had guns. You had to be careful to stay alive. Things were terrible there; because Hitler was in power, the Nazis could do anything they wanted. They just shot Jews, and no one questioned their actions because there were no laws against what they were doing. It was war.

When we were walking in lines, the SS would sometimes tell us to stop, and each person had to count off. They would shoot every ninth person in the line. One time, my brother Ernie was the eighth person and the person next to him was shot.

There was nothing I could do when I saw people getting killed. I didn’t have a gun, so I couldn’t fight. I was trying to save my own life and couldn’t help the guys who got killed. If I saw the Nazis doing something in one place, I went the other way; this is how I survived. I wanted to survive. I wanted to live healthy and free. I was afraid, but I figured I wouldn’t let anyone kill me.

I was very skinny when I was in Austria, I can’t even explain how thin I was. They didn’t give us enough food, but I was strong.

I was almost fourteen years old when we were liberated by the American army on May 5, 1945.