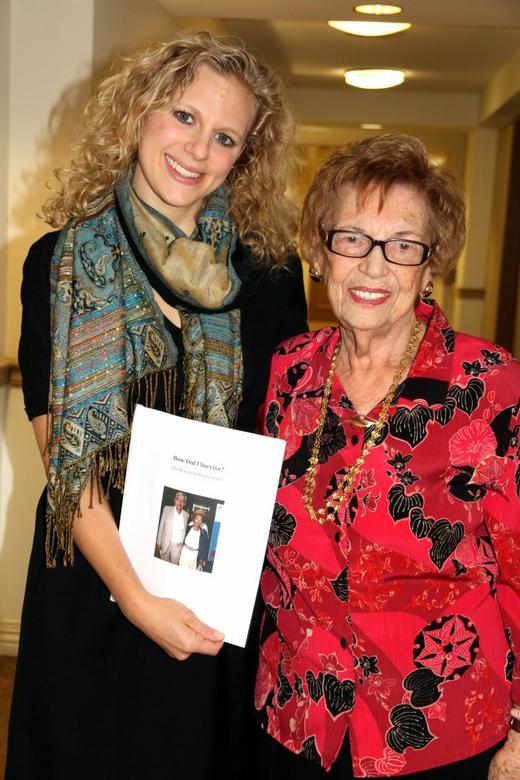

Regina Perlis

Born: Brzeżany, Poland (now Berezhany, Ukraine), 1925

Wartime experience: Ghetto, forced labour and hiding

Writing partner: Meredith Landy

Regina Perlis was born in Brzeżany, Poland (now Berezhany, Ukraine), in 1925. At the onset of the war, she and her family were under Soviet occupation; by the summer of 1941, Germany had invaded the Soviet-occupied areas and Brzeżany was under the Nazi regime.

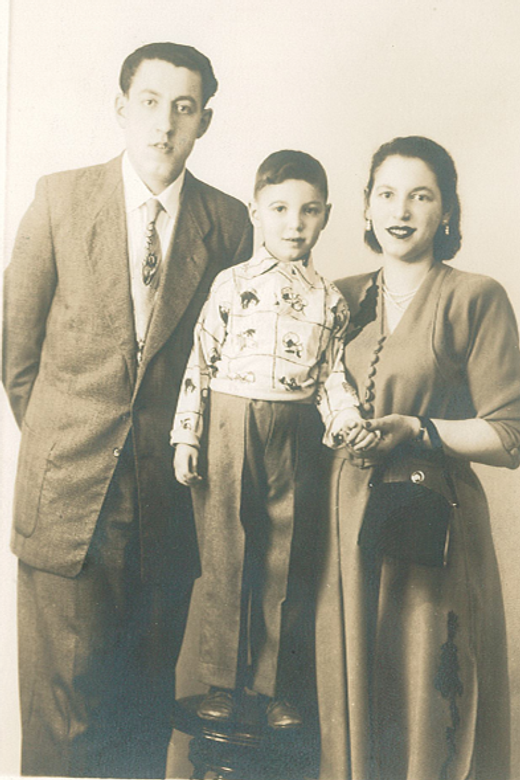

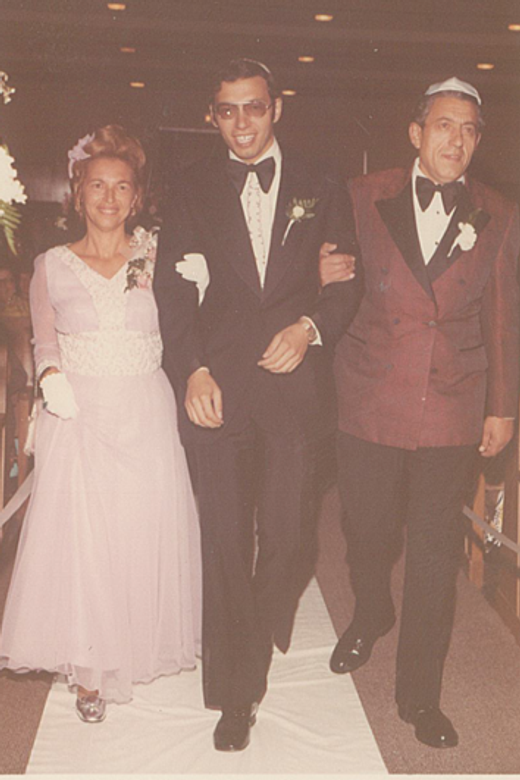

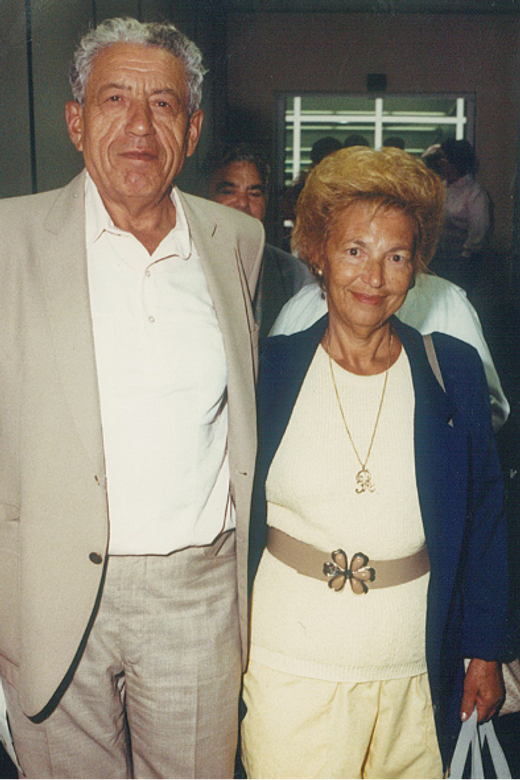

Regina and her family were eventually forced into the Brzeżany ghetto and then into the nearby ghetto in Rohatyn, where Regina was sent to work. Regina caught typhus in the ghetto and went into hiding there; during that time, her parents were killed. Regina and her younger sister escaped from the ghetto in spring 1943 just before it was liquidated and were eventually able to hide in a farmer’s basement and then on the edge of his farm. They were liberated by the Soviet army in 1944 and reunited with their older sister. After the war, they lived in the Föhrenwald displaced persons camp, where Regina met her husband, Chaim. They married in 1947 and had a son in 1948. Regina and her family immigrated to Canada in 1952, settling in Montreal, where her second son was born. Regina worked and raised her family, and after her husband retired, they moved to Toronto to be closer to their children and grandchildren. Regina Perlis passed away in 2023.

Suffering in the Ghetto

We had to give the Germans everything we owned — we were not allowed to keep any of our own things. We were forced to leave our house, and my whole family was taken to the ghetto in Brzeżany (now Berezhany). Life in the ghetto was hard. We were there for about two years. Some people thought it would be better in Rohatyn, so we went to another ghetto in Rohatyn. I’m not sure how we got there. Someone must have taken us. When we got there, some Jewish people in the ghetto told my family we would have to give one of the children in our family to work in the ghetto. My brother was younger, and men were more likely to get killed. My older sister must have been eighteen at the time, but she was tall and very attractive, and my mother did not want to send her. So I said I would go. One child from every family had to work, and in our family that was me.

The work there was so hard that I cannot describe it. Cleaning was nothing. But I had to carry heavy things, constantly lifting and schlepping them. When I woke up in the morning, I would see a lot of dead bodies on the sidewalk. I couldn’t let it get to me.

One day I snuck out of the ghetto to try to buy some food. I did not have any money, so I must have tried to exchange clothing for food at a gentile-owned store. A German police officer noticed the Jewish star I was forced to wear. He took me to the police station and said they were going to kill me. I always think about this because I’m not really sure how I wasn’t killed. There are certain things that are still hard to remember, but this is what happened to me.

My sister was hidden in the ghetto the whole time we lived there. She entered her hiding spot through an opening in a cabinet in the kitchen that led to the basement, and there was another opening from down there. She had so little air down there and hardly ever any water to drink.

My parents sent my brother away to hide outside the ghetto. They thought he would have a better chance of survival than if he stayed in the ghetto. We all thought it would be better if he tried to escape, so he and three other boys escaped together. Two days later, a policeman who was working for the Germans but who was very good to the Jews told us the boys had been killed. My brother was only fourteen or fifteen at the time.

***

While living in the ghetto, I was forced to work in the Arbeitslager, which was like any German forced labour camp. We all had to do what they told us. I worked in the garden and carried heavy things and cleaned all kinds of other things. It was miserable. There was food once a day at the most. I worked in the fields and other places, work that was incredibly difficult. In the mornings at five o’clock we would go downstairs to take a shower. Once when I went to take a bath there were a few hundred children, mostly my age, working very hard. I will never forget this. There was a brother and a sister working in the garden, and the sister hadn’t eaten anything in a long time. So her brother gave her something from the garden. He was killed for doing that. I couldn’t stand it.

About a year after being forced into the ghetto, I got sick with typhus. There were others sick with typhus as well, and we were told we would be taken to a big city like Lemberg (now Lviv, Ukraine) to be killed. I had a fever, and when I fell nobody picked me up; they weren’t supposed to. I can’t recall how I stood up without help. Then, instead of bringing us to Lemberg, they brought us back to the ghetto, and I remained sick there. My mother caught typhus from me. Every day officers would come to see if there were any sick Jews; if there were any, they would take them away to be killed. We were not allowed to ask questions. They took what they wanted. Someone would warn us when they were coming so we could hide my mother in a closet. One day the officers came without any warning and they saw her and took her and put her in the hospital. When my father went to check on her, he found out that everyone who had been taken to the hospital had been killed.

My parents were both killed while I was sick with typhus in the ghetto. My mother was only forty and my father was only forty-three. When my parents were killed, my younger sister and I were hiding together in a basement in the ghetto where we had a loaf of bread and a bit of water to last us a week. My older sister and a friend of hers were hiding elsewhere in the ghetto. I didn’t hear about my parents’ deaths until a week later. I was sixteen at the time. I couldn’t believe my parents were dead. I never thought there was going to be life after that. I constantly thought I would die that day or the next.

When I woke up in the morning, I would see a lot of dead bodies on the sidewalk. I couldn’t let it get to me.

Precarious Refuge

In the spring of 1943, we heard that the ghetto was going to be shut down and that everyone still there would be killed. I then escaped from the ghetto carrying my younger sister on my back. She was five years younger than me, so she was still a kid at the time. We went from place to place, wandering with no idea where we were. We ended up in a little town, the name of which I cannot remember, where a man who knew my parents lived. His last name was Wisofsky. When this man had had problems, he would come to my father and my father had helped him. This man hid us at the end of a hall in the basement of his farm. His wife knew we were there, but they did not tell their children because they were afraid they would say something, tell someone. On his way to work, the man would bring us food. There were some days when we didn’t have food or water.

One time I went upstairs because I couldn’t breathe in the stuffy basement. There was a German man who asked me what I was doing there. I didn’t have the nerves I have today. I tried speaking to him in Polish and said, “The Ukrainians are coming and I had to hide myself.” At the time, the Ukrainians and the Polish were fighting, so I told him the Ukrainians were there, that I was scared so I left my family’s house to hide. In reality, of course, I was Jewish and scared of the Germans, but I couldn’t tell him this, so I pretended I was a gentile hiding from the Ukrainians. While he was talking to me, another soldier with a gun entered and also asked what I was doing there. The first one told him what I had said, and they both left me alone.

The woman who owned the house was watching all this from a window and was worried I had told them they were hiding me. She came in and said to me, “I love you, but I have a granddaughter. If they kill you they will kill me and the baby too.” What could I say to that? So we had to leave. We needed to find a new place to hide. We hid at the back of the Wisofsky family’s farm, at the edge of their property, for six or seven months. My feet were frozen completely from the snow. Every night I worried someone would see me or hear me.

In 1944, the Soviet army arrived and pushed the Germans out, and things got better. I don’t remember where we were or what time of year it was. The man who owned the farm came to tell us the Soviets were coming. I couldn’t believe it. It is hard to describe what I felt at the time because of how much I had lost.

***

My sister and I were eventually reunited with our older sister, who had been hiding with a friend of hers. I never asked her how she survived the war; she didn’t like to talk about those things. After we were reunited, we went to a city near Munich, Germany. Everyone was scared to go to the city because we still believed the gentiles were going to kill us. We went to the Föhrenwald displaced persons (DP) camp, south of Munich and one of the largest DP camps in Europe. We lived there for about three years. There were so many people trying to leave the country and rebuild their lives. Some people went to Israel, some went to Canada and some to the United States.

While living in Föhrenwald, I was introduced by a friend of mine to a man named Chaim. He was from Wełna, Poland, near the large city where she was from. Chaim and I knew each other for two or three months before getting married in June 1947 in the DP camp. My older son, Morris, was born on December 5, 1948. He was named after my father, Leibish, and my husband’s father, Morris. My husband and I thought about moving to the United States or Israel, which was where most people were going. We never even considered Canada because we did not have any family there. However, we couldn’t get papers for the United States, and I did not want to stay in Germany. We immigrated to Montreal because that’s where we were let in. It took four weeks to get the papers. We got here and didn’t know anybody. It took me five years to realize I was in a free country and I could say and do what I wanted.