Aaron Nussbaum

Born: Sandomierz, Poland, 1931

Wartime experience: Hiding, camp

Writing partner: Lisa Newman

Aaron Nussbaum was born in Sandomierz, Poland, in 1931. After the German occupation of Poland in September 1939, his father was no longer allowed to manage his own business, and in the spring of 1940, his father was arrested and then taken to the Buchenwald concentration camp.

His father died in a Nazi camp in 1942. In the fall of 1942, Aaron, his mother and his younger brother fled to Warsaw and went into hiding. After their hiding place was revealed, Aaron and his family went to Hotel Polski in Warsaw, where they were led to believe they could escape the war as exchange prisoners for German citizens in foreign countries. Instead, they were sent to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in the summer of 1943. In April 1945, they were put on a train headed to the Theresienstadt ghetto and concentration camp; several days later when the train stopped near Hillersleben, Germany, Aaron, his mother and brother were liberated by the American army. After the war, Aaron left for Palestine. In 1952, he visited his mother and brother in Toronto and decided to stay with them. Aaron worked in a garment factory and then in construction, eventually opening his own hardware store. Aaron raised two children in Toronto with his wife, Bella (née Goldman), who passed away in 2011, and has several grandchildren.

Aaron and his family in their home before the war. From left to right: Aaron’s mother, Regina; his brother, Shlomo (Mark); Aaron; and his father, Abraham. Sandomierz, Poland, 1936. Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Mark Nussbaum.

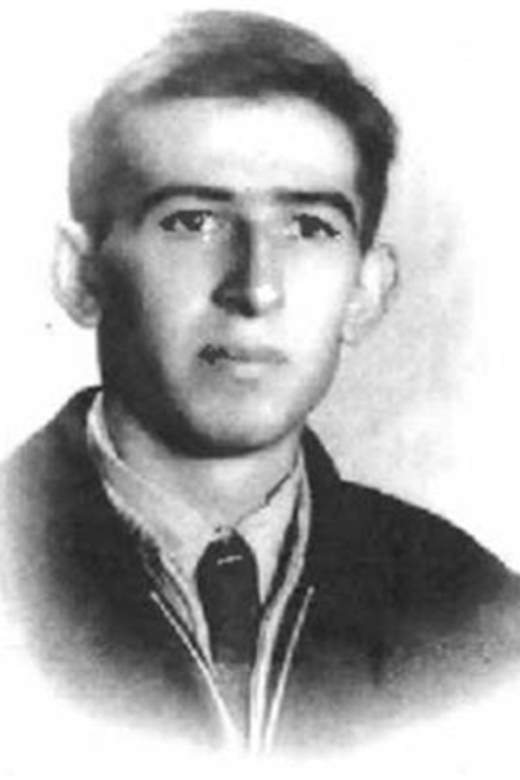

Aaron and his younger brother, Shlomo (Mark). Sandomierz, Poland, circa 1938. Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Mark Nussbaum.

Fight Back

We had a very good life when I was growing up; we were one of the few wealthy families in Sandomierz. There were about four hundred Jewish families, over two thousand Jews, in the town — about a dozen very wealthy families like ours, some who were middle class and a lot of poor Jews. The wealthy Jews looked after the poor ones, in the Jewish tradition of g’milut chasadim, the act of caring for others. My father did extremely well in business. He was so successful that he supported his parents and his grandparents and other members of his family, some of whom were quite poor, like my great aunt, my grandfather’s sister, who had a very small candy store with her husband and a very large family to feed. We felt safe and secure in our town; life was fine.

The apartment we rented was a block and a half from my father’s business. A few years ago, I visited Sandomierz and saw the building we had lived in, and it was in terrible shape and had not been maintained well. We lived in a Jewish neighbourhood, as did most Sandomierz Jews; only some Jews lived in mixed or non-Jewish neighbourhoods. There were eight or nine apartments in the building where we lived, and all the other families were Jewish like us. Our apartment had a kitchen, dining and living rooms, and one bedroom. We had an icebox and electricity, but no running water in the kitchen. I don’t remember what kind of stove we had. A Polish woman cooked and cleaned for us. She stayed at our house six days a week, living in our kitchen, where she had a bed. When it came time to prepare for Pesach or other holidays, she did the work.

My father had contracts with the army for installing electricity in the two military camps (one for officers and one for conscripts) near Sandomierz. Similarly, my grandfather was said to have had “golden hands” and could fix anything; he put together the first radio in our town. My father also had a store where he sold electrical equipment and appliances, like radios and phonographs, and because of his good connections with the local Polish people, my father was the exclusive agent for the Polish-manufactured Kaminski bicycles. (The Polish government protected this manufacturing company by imposing tariffs on all imported bicycles.) My father had two or three employees in the store, one of whom was Chilek Gutholtz, who ate lunch in our house every day, as well as a couple of others who assembled the bicycles he sold.

My father built an apartment building outside our town in 1936–1937. It was the first modern building constructed in Sandomierz in fifty years and had indoor plumbing, but no elevator. My cousin Tzvika and his parents lived in it, as well as my aunt Anne (Chana), my father’s sister, and uncle Shulim.

My family were modern Orthodox Jews; we were observant but not overly extreme. My father was a traditional Jew, religious. Every morning he put on his tallis (a prayer shawl) and tefillin (phylacteries, small boxes containing scrolls of parchment), and then davened (prayed). We went to shul on Saturday, and my father and my zaidy sat right in front of the bimah, the raised platform where the Torah was read. We were cohanim, which meant we were given these seats at the front because we were descended from priests. Both of my grandfathers were religious, though my father’s family was more liberal than my mother’s. After shul, I would go to the bakery to pick up the cholent, a traditional stew, for my mother. Jewish conscripts, anywhere from a dozen to twenty, used to come from the local army camp to go to our shul, and every family would take a conscript home for a meal, bringing them back to the shul after Shabbat.

My father kept his store closed on Shabbat and on Jewish holidays, but he did not wear a kippah, skullcap, at work. We had a kosher home; in those days, every Jew had a kosher home, even if they weren’t religious. And 95 per cent of the Jews in our town observed Shabbat. My father’s father used to take me to the movie theatre beside the fire hall in Sandomierz, but I don’t remember the names of any of the movies I saw with him. I did not wear a kippah when I walked around town, only in cheder, the Jewish school, and in shul.

When I was young, about five years old, I attended a cheder, where a melamed, a religious teacher, taught us the Tanach (Bible) and davening. It was mostly aleph beys, which is what we called the Hebrew language based on the names of the first two letters of the alphabet. I remember the melamed very well because if we didn’t behave, he would hit us with a ruler. We would take our hands away so he couldn’t hit us, and that would make him mad.

In 1938, I started attending a local public school. Even today I speak, read and write fluently in Polish, even though I had only three years of school. We had lunch at school and then went to cheder after school ended at two o’clock. Out of about the twenty or so kids in my public school classes, six or so would be Jews. Although I went to school with gentiles, who we called goyim, many were antisemitic and so I didn’t associate with them. At recess, the Jewish children used to stay in the classroom because we were afraid to go out to the playground. I remember very well one Jewish boy who was strong and tall; he had spent three or four years in Grade one. The Polish children were afraid of him, and he used to tell the Jewish boys to come outside, not to be afraid. He was beaten up sometimes, but he was not afraid.

We played games like soccer and hopscotch on the outskirts of town, near the military camps. Soccer was the main game in Poland and later, too, in Israel. There were two Jewish soccer teams in Sandomierz, Betar and Maccabi, because the Polish people did not let Jews play on their soccer teams. When the Jewish and Polish teams played each other, if the Jewish team was winning, the Polish players kicked them in the legs. There were droschkes, wagons with horses, standing by to take the Jewish players back to town. We would go to watch the games when the Jewish teams played, but not when the Polish teams played each other.

The rabbis in those days taught us: when the goyim lift up a hand, you should lift up your legs to run. They taught us to run and hide. Now it is different; we have to fight back. Now we have the Jewish Defense League and other organizations; even if you don’t always agree with them, we have to fight back.

There was a fake wall in the apartment, and if we heard anyone coming, we would hide behind the wall, crowded together, not moving. We could never go outside. We had to bribe Polish police to leave us alone and also had to pay for being hidden.

Hotel Polski

In 1940, I was living at home with my mother and brother, along with my father’s family, my mother’s parents and her sister who was expelled from Radomsko and had come to live with us. It wasn’t until September or October 1940 that we realized that the Germans had come to kill the Jews. We heard news spreading from town to town about how Jews had been taken to concentration camps by the Germans and had never come back.

In September 1942, we went into hiding. A Jewish woman we knew (Menashe Laiman’s sister, who looked “Aryan”) had a Polish housekeeper who could provide hiding places in Warsaw and she brought us there. We were hidden in the apartment of a woman who had three sons, the Gruszewskas, and we all had to live in one room. There was a fake wall in the apartment, and if we heard anyone coming, we would hide behind the wall, crowded together, not moving. We could never go outside. We had to bribe Polish police to leave us alone and also had to pay for being hidden. Being one of the wealthiest Jews in the town, my father was well connected with the local Poles. He had many Polish friends and business associates, and this ended up helping us survive. My father knew he had to protect his family, and so before the war he left money with a local Polish engineer, a nice man who lived down the street from us. This man brought us money every couple of months during the time my mother, brother and I were in hiding in Warsaw so that we could pay those who were hiding us; I don’t remember his name.

There came a point when we could no longer hide. The extended family of the people hiding us (not the family itself), told the Polish police about us. We had heard about Hotel Polski from my aunt Frydka, who lived on the “Aryan” side of Warsaw. So in June 1943, like many other Jews who were hiding in Warsaw up until then, we left our hiding place, took our suitcases and went to the Hotel Polski, a hotel in Warsaw.

The Germans had let people know that if Jews came to the Hotel Polski the Germans would exchange these Jews for German citizens who were in Palestine or other foreign countries. It was supposed to be a way to get out of the country. There was a group from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and a group in Switzerland that arranged for false papers for emigration to Palestine or South America. The papers for South America cost more than those for Palestine. We registered at Hotel Polski for the exchange to Palestine. There were a couple of German colonies in Palestine, one in Haifa and one in Jerusalem. Six of us registered: my mother and brother and me, my aunt Anne, my uncle Shulim and my cousin Tzvika, who had been born in Palestine. In 1935, my father’s brother, Yosef, and his wife had gone to Palestine, but times were very bad there due to the fighting with the Arabs, and in 1938 they returned to Poland with their son, Tzvika. Yosef and his wife perished in the Holocaust, but Tzvika survived because he legitimately got papers for emigration to Palestine at the Hotel Polski and was therefore able to go to there in the fall of 1945.

We were given different names that matched the names on the certificates that were available. My mother had to take the name Marcovich, while I was to go under the name Nussbaum since Tzvika already had his certificate in that name and I went as his relative. We had to pay for these papers.

We stayed in the Hotel Polski for about a week, waiting for them to take us to a camp where we would be put up until we could be exchanged and leave for Palestine. At the Hotel Polski, there was a Mr. Rubenstein who was chairman of the Judenrat in Ostrowiec. (His wife was from Sandomierz and her family had lived in the same building as us.) A German officer had told Mr. Rubenstein to stay behind and he would take him to Hungary, to safety. My mother had a lot of confidence in Mr. Rubenstein and thought that if he and his family were staying behind, we should stay behind with them. Even though I was only eleven years old, I said, “No, I don’t have a good feeling about him.” I told my mother we should not stay, that we had to get on the truck and go. And so we did, and that saved our lives. Mr. Rubenstein and the others who stayed behind were taken to nearby Pawiak prison and shot in the courtyard there. If we had stayed, we would have died, too.

From Hotel Polski we were taken by truck to the train station and sent with our certificates to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. We thought we were going to be exchanged for German citizens in Palestine and eventually travel there. It took a day or a day and a half to get to Bergen-Belsen and we were still in good health when we got there. The guards put us straight into barracks, men separated from women with children, in triple wooden bunks, one person in each bed. I was young enough that I stayed with my mother and brother, Mark. We were given bread that we had to measure to divide equally among us. Our barracks held sixty to one hundred people and three times a day we were all called out to be counted. It would have been impossible to escape; the fences were electrified. In Bergen-Belsen, I turned thirteen; my mother told me it was my bar mitzvah and gave me some of her ration of bread so I would have extra to eat that day.

When the Germans in Bergen-Belsen saw that the exchange was not coming through and realized that the papers we had were false, they started to do selections among us, choosing who to kill. First, they took the people who had signed up to be sent to countries in South America; the Nazis sent them to other camps to be gassed. My aunt Frydka, who had been living on false papers in Warsaw, had registered at Hotel Polski to go to South America. If she had registered for Palestine, she would be alive. Those of us who registered for Palestine survived.

When the British arrived in Hanover, on the outskirts of Bergen-Belsen, the Germans put those of us remaining in our part of the camp on trains to be sent us to another camp, Theresienstadt. But the American army was already in Magdeburg, so the train stopped and we prepared to be unloaded — we were going to be taken to the Elbe River to be shot. It was then, on April 12, 1945, in Farsleben near Magdeburg, that the American army liberated us while we were still on the trains. Eventually, the German guards all ran away. The first American soldier to jump down from the tank on the highway and start shooting at our guards on the train was a young Jewish man from Philadelphia named Moshe Cohen, a Białystok Jew. None of us spoke English, except for one man who had lived in the United States before the war and had been trapped by the war while back in Poland to visit his family; he translated for the rest of us. The Americans took us to Hillersleben, Germany.

***

Years later people asked me, what made you able to survive? I wanted to live, and I still do. I remember telling my mother, “We will survive.” I was always optimistic, even in hiding I said, “Ma, we will survive.” Life is not easy.

If my father could see my life, I think he would be proud of me. I am doing very well, and Mark, my brother, is doing very well, too. I am proud to be a Jew and to have given my children and grandchildren a Jewish education. All of my father’s twenty-eight great-grandchildren have gone to Jewish day schools.