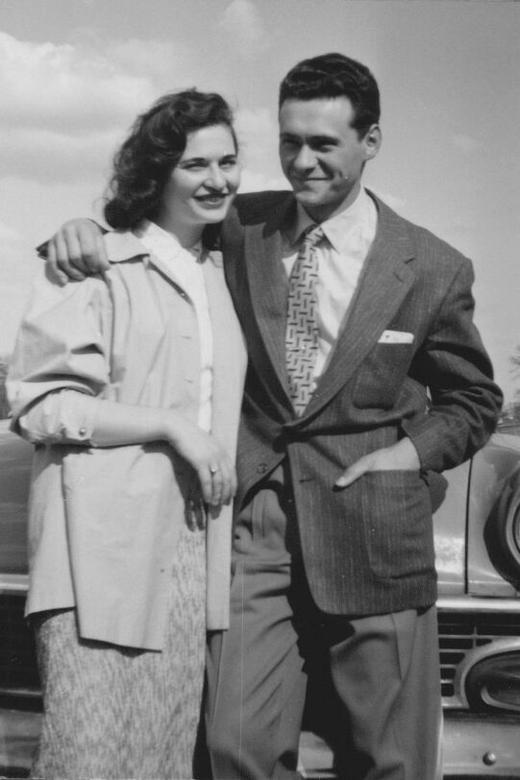

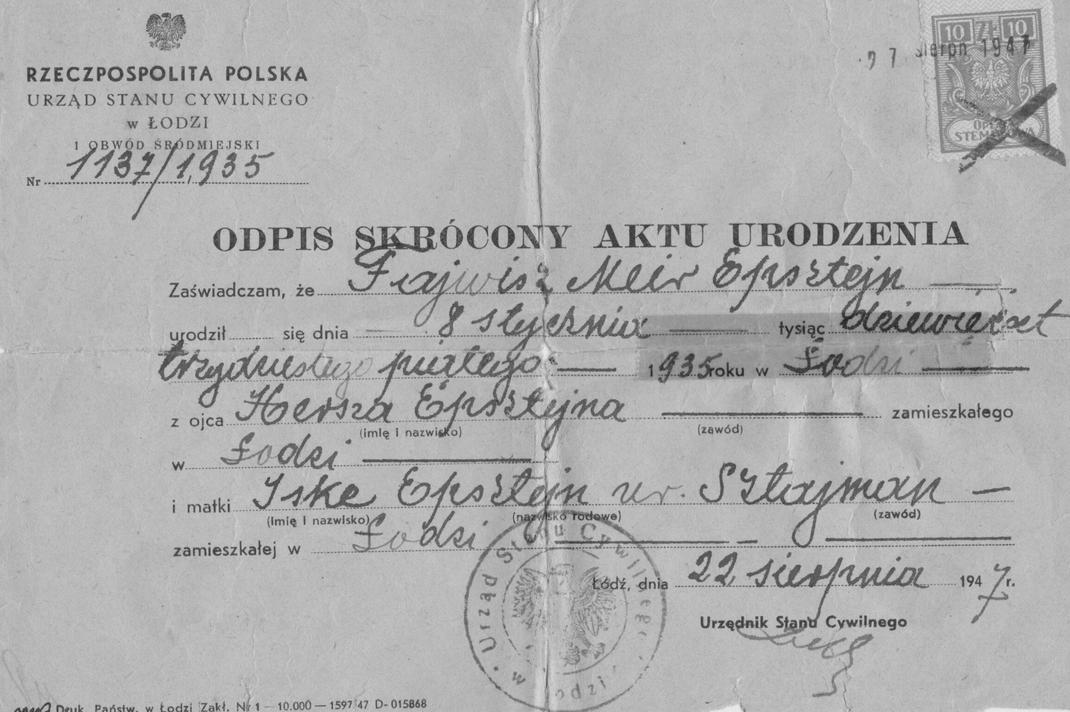

Philip Epstein

Born: Lodz, Poland, 1935

Wartime experience: Ghetto, hiding

Writing partner: Fran Weisman

Philip Epstein was born in Lodz, Poland, in 1935. A couple of months after the start of the war in 1939, Philip and his parents fled Lodz, thus avoiding being trapped in the Lodz ghetto.

He and his parents were briefly held in a ghetto in Rovno (now Rivne, Ukraine), and were then sent to work on a nearby farm. They escaped a roundup on the farm and lived in the Tuchyn (Tuchin) ghetto until September 1942, when they escaped the ghetto during an uprising. Philip and his family hid in the Lipiczanska Forest in Ukraine, where they stayed for close to three years, spending about seventeen months of that time in an underground bunker. During this time, Philip’s father was killed by local farmers. Philip survived with his mother, and in 1949 they immigrated to Israel with his stepfather, Kopel. Philip moved to Canada in 1956, settling in Toronto, where he met his wife, Molly, and raised a family.

I don’t remember feeling afraid. I was a child with my parents, and as long as they were with me, I didn’t worry or feel insecure.

On the Run

There was a lot of antisemitism at this time in Lodz, and the situation for Jews was worsening. The Germans had been cutting the beards off Jewish men, beating them, taking away their businesses, burning their stores. This happened even before the ghetto was organized. My father was a big tall man who stood out in a crowd, and one day the thugs caught him on the street and wanted “the big Jew” to push a cart filled with coal. This was almost impossible, but he didn’t have a choice. Move the cart or get shot. The cart was so heavy that when he actually moved the wagon, he sunk to his knees in the dirt. The Germans were so impressed that they let him go. My mother told me this story shortly after the war.

After the coal-cart incident, my parents decided to leave Lodz. In November 1939, we left the city along with my aunt Tamara, her husband, Moishe Zeitman, my uncle Yechazkel and his new bride, and my mother’s youngest sister’s husband, Gershon. My mother’s youngest sister, Gittel, was very young and thin, and my grandparents did not feel she was strong enough to go with the group. They told the others to go ahead and to leave Gittel with them until they were settled, at which point they would send her. They had no way of knowing that staying in Lodz was so much more dangerous. They would later be trapped in the infamous Lodz ghetto, and we never saw or heard from our entire family again. On the run, my uncle Yechazkel’s wife was the first one murdered. She was shot shortly after we left. Her name is lost to us.

I clearly remember when our family fled Lodz in November 1939, a few months before my fifth birthday. I was unaware of the gravity of our situation since I was so young and my parents protected me from what was happening to the Jews. I don’t remember feeling afraid. I was a child with my parents, and as long as they were with me, I didn’t worry or feel insecure. I didn’t really understand what war was, but I knew that my family was on the run because we were Jewish and that the bad people hated us. Even though I saw and heard terrible things, I felt safe because I had my father to protect and care for me. My father carried me most of the time on his back and gave me sweets to suck on while we were walking. When we slept, my father put me on his chest so I would not feel the cold from the ground.

The only thing my mother took with her when we left Lodz, besides the clothing on her back, was my bottles. A few days later, we were running in the forest being shot at and my mother dropped the satchel of bottles. We all learned that day that a hungry child will eat, bottles or no bottles.

We couldn’t walk on the road because we would be easily seen. My father was somewhat familiar with the area and had some knowledge of the terrain and where we could walk. We usually had to sleep outside but sometimes we went into a farm and hid there for the night. It was dangerous, and the farmers didn’t know we were there. My mother told me that we were headed for Mezhyrich, a village in the Ukraine where my father thought we might be safe. He had business contacts there and hoped he could work for a place to sleep and some food. What our group did not know at the time was that the Germans were following quickly behind us as they moved through Eastern Europe.

I don’t know how long it took or whether it was by chance or design, but we eventually arrived in Rovno (now Rivne, Ukraine). The gentiles who knew us didn’t want to help because we were Jews and if they were caught hiding us, they would be killed along with us. In the fall of 1941, there was a notice posted saying that all the Jews had to report to the ghetto, so the following day we went to the ghetto, declared that we were Jewish and that we had run away from Lodz. We were given space. I don’t remember too much about our time in the ghetto. Our family was seven in total. There were my parents, myself, Tamara and Moishe, Gershon and my father’s younger brother, Yechazkel. I’m not sure, but probably we were all together in the one room. I don’t remember anything about food or what I did during the day. I don’t think the adults went out to work. I think we were in the Rovno ghetto only for a few months when my father was singled out to run a farm near the ghetto.

The Germans had established one big farm for the area where they collected all the prime cattle, bulls, horses and pigs. As they plundered Europe of its arts, monuments and sculptures, they did the same with prime animals. That the population would starve was of no consequence to them. Somehow, the Germans found out that my father knew the cattle business, so they came to the Rovno ghetto and told him that he could take his family with him to work on the farm. So we went to the farm, my father, my mother and me. This was a large cattle farm, and my father needed farmhands to help him. The Germans gave my father permission to get help from the ghetto. My uncles were tailors, but my father told the Germans that they were his partners in the cattle business so that he could get them onto the farm.

At that time, my aunt and her husband had an infant boy, Nissim. I cannot remember when and where Nissim was born but I do remember playing with him on the farm and how happy I was to have another child with me. Although we were working for the Germans, we were given a nice home with electricity that was big enough for the eight of us. There were about ten or twelve guards and one captain in charge, and my father worked under him. My father was responsible for everything on the farm. I would estimate that we were there between four and nine months. It was good, nobody bothered us and we had enough to eat. We provided the soldiers with things like fresh eggs and butter, and they were happy with that.

There was a collie dog on the farm that Nissim and I played with and loved. One day, the dog was growling at a soldier, who was sadistically provoking him. The soldier aimed his pistol and shot him. I remember that moment clearly; it was the first time I understood the situation and that we were not safe at all.

On the farm, one German soldier had a boy my age and had taken a liking to me. One night, he came to my father and told him to leave with our family right away. He told him to take whatever we could carry and run to the forest. Even though my father didn’t want to believe him, he listened. We waited until dark and then we all hid in the nearby forest and watched. In the middle of the night, two trucks came to the house to round up any Jews. The officer had saved our lives, for now.

Uprising in the Ghetto

We headed to the Tuchyn (Tuchin) ghetto in the Rovno district, I assume because it was the only place we were familiar with. By this time, I think my father and family knew what was happening to the Jews. It would have been from our own experience and news that was passed around. We had heard that the Germans came in one night to another ghetto and burned it down, with the Jews in it. You could see the fire burning and you could smell the burning flesh from kilometres away. In another ghetto, all the Jews were taken into the forest and shot.

In the Tuchyn ghetto, there was a resistance group, and by the fall of 1942, they knew that when the Germans and Ukrainian collaborators came in, every Jewish man, woman and child would be shot or burned. They decided that they would burn down the ghetto themselves when the Germans approached. Even though many would perish, at least some would have a chance to run to the forest. Guards were set up around the ghetto with shofars, trumpets made out of a ram’s horn, that they would blow when they saw the trucks coming.

One night in September 1942, the signal was given and the ghetto started to burn and the fighting group started to fire their weapons. It was mayhem. Those who could run did so. Most were shot in the ensuing chaos but some made it to the forest. I remember seeing old men burning who had wrapped themselves in their tallisim, their prayer shawls. I did not cry for these old men because I believed that their tallisim would protect them, that God would protect them. I was a young boy and my father was a religious man who I now realize gave me this belief to protect me. I do remember my father and my mother and I running right into a German soldier. He aimed his gun at us but he had no bullets left. Again, fate had intervened, and we were spared. He reloaded, and we heard someone else being shot instead of us.

After the war, we found out that most of the Jews of the Tuchyn ghetto did not survive. Of the three thousand original Jewish inhabitants of Tuchyn, only twenty were still alive when the town was liberated.

We were now in the Lipiczanska Forest in the Ukraine, and soon we connected with another group of about four or five people. None of us knew where we were going. We kept on going for a few days and then the group started to get larger. We ate berries and whatever else we could find. Some people got diarrhea and died from what they ate, so we had to learn what was safe to eat.

As our group grew, so did our problems. One problem was the children. Some of the children were around my age, some were older, some were younger and some were infants. The crying of the infants and young children was a danger. Night fell, terrorizing fear set in, children cried in hunger and despair, and self-declared leaders of the group made decisions. Younger children and infants were to be killed so that they would not endanger the rest of the group. My father would not give me up, and so we left.

At the time, my cousin Nissim was fifteen or sixteen months old. My aunt Tamara’s husband, Moishe, said, “Give him; the war will be over and we will have more children. There is no other choice.” She wouldn’t let him go. Moishe left and walked into the woods. My father asked her to take the baby with us, so what would happen to one would happen to all of us. But she was frightened, she was starving and she was young, only twenty-two years old. The baby was crying and already sick, so she gave him up. Rags were shoved into Nissim’s mouth; he was placed into a haystack and he was never spoken about again. After my aunt Tamara gave the baby up, she crawled under a haystack and was mewing like a wounded animal. Her husband came back for her and found her. They eventually located us and then we continued walking. I don’t remember if I cried; I don’t remember if I was afraid. I remember that one minute I saw Nissim and then I didn’t see him anymore. The pain of his loss remains with me today, so many years later. I often think that if Nissim had survived, I would have a real close cousin.

We continued on, myself and my parents, Moishe, Tamara and Gershon. I remember being in the forest. We walked by night and hid during the day, eating whatever we could find. One day while we were hiding, non-Jewish Ukrainian partisans spotted us. My father could speak Ukrainian and although we were terrified, he told them who we were. They didn’t hurt us and they told us that they had to leave the area, showing us the bunker they were abandoning underneath the ground. They had to move on, but we could hide there. To get to the bunker, we had to climb down about four feet. The men would jump in and then help the women and myself down. Then we crawled horizontally for about twenty feet and then again down into the bunker. In the bunker, we were able to stand up. This is where we stayed for the next sixteen or seventeen months. My father found another couple, who were schoolteachers, and allowed them to join us.

We were eight people in the bunker. We slept side by side, and if one had to roll over then everybody had to roll. I slept between my mother and my father. There was so little food and we were starving, but I felt safe with my father. There was a pipe in the bunker that went just above the ground so that we could have a small fire. The fire kept us warm, and we used it to melt the snow for water in the winter and for cooking and drinking. While we were hiding in the forest, all we knew about were the ghettos, because we had been in the ghettos and seen the suffering, but that is all we knew. We had no way of knowing the extent of what was happening to the Jews. We were in the forest and knew only what was going on around us.