Erika Erdos

Born: Trnava, Czechoslovakia (now Slovakia), 1929

Wartime experience: Hiding

Writing partner: Judith Levine

Erika Erdos was born in Trnava, Czechoslovakia, in 1929. In 1940, Trnava became part of Slovakia, a client state of Nazi Germany, and Erika and her family lived through the rising persecution of the Jewish population.

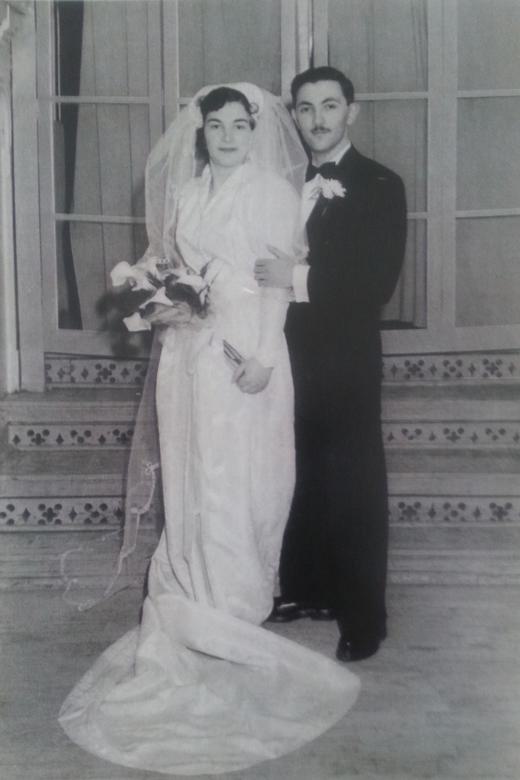

Through luck and the support of her father’s employer, her family avoided the deportation to the Nazi camps. After the German occupation of Slovakia in 1944, she, her parents and her younger sister hid in the home of one of her father’s former business associates until they were liberated by the Soviets. They immigrated to Canada in 1948 and lived in rural areas in Ontario, working on farms before eventually moving to Toronto. In 1951, Erika met her husband, Steve, and they raised a family together.

Searching for Help

In the fall of 1944, the situation changed for the worse — there was an uprising against the fascist regime in Slovakia. In order to suppress it, the Germans marched into the country and took over the government. This occupation made all the exemptions for the remaining Jews invalid, and Jews left in the country were immediately rounded up to be deported.

I marvel at the genius of our father. He had feared something like this could happen and had located a couple of peasants in the surrounding villages who might be willing to hide us in just such a situation. He’d even arranged for regular payments to be given to anyone who would take us in. Within minutes of learning about the German occupation, we were all ready to leave.

Our family set out in search of a hiding place, each of us carrying a small bundle of clothing. We made the rounds that day, walking many kilometres through three villages, but were turned away from every door — sometimes rudely, most times regretfully. “Sorry, Mr. Blum, I have a wife and children too. I couldn’t risk their lives for you.” Or, “If it were up to me, I would do it; you know me, Joe. But the old woman, she won’t let me.” And most frequently, “I’d take you and the Mrs., but I can’t take the children; they couldn’t lie still and would endanger our lives too. After all, if they find you here, we’ll be as dead as you.”

By nightfall, we had found shelter, only to be put out the next night. After that, we spent two weeks in the attic of a farmer’s cottage. The farmer lost his courage a few hours after he took us in and tried to send us away, but we begged and pleaded and refused to budge. There was nowhere else to go, except to our deaths.

When the farmer’s wife decided to starve us out, we took one more desperate step. Early the next morning, disguised as a peasant girl, I walked to the next village — Zeleneč — to find the last house on my father’s list of possible shelters. It is difficult to appreciate the danger of such an expedition, not the least of which was the threat of being recognized by locals. During those days, we didn’t know who could be trusted. We had agreed that if I didn’t return by nightfall, the rest of the family were to follow, similarly disguised, since that place was really our last ray of hope.

The house belonged to another of my dad’s former business associates, Mr. Havko. His daughter, Francka, lived alone in one of two flats in old Havko’s house, her husband having left her for the United States some twenty years earlier. He may not have been pleased that his young wife preferred women. The other flat was occupied by Mr. Havko and his other daughter, her husband and their two young children.

The house was built of mud, with clay floors and a thatched roof. Behind the second apartment, there was a tool shed and then a barn, where an old horse was kept. A ladder was leaning against the back of the house and provided access to the loft. It was in this loft, above the tool shed, that we made our home. We spread some straw under us, and Mr. Havko piled the straw high in front of us so we wouldn’t be seen from the back lane or the fields, since there was neither a door nor a wall closing the loft up at the back of the house.

We were barely settled when the Germans flooded into the village. Francka, living alone in the two-room part of the house, was listed as having one spare room, and she had three German soldiers assigned to her lodgings. You can imagine that there was no possibility of her cooking a meal for a family of four — she would have aroused their suspicions immediately.

The butcher and the grocer would also have wondered at the quantity of her purchases. So food was scarce for our silent, frightened family in the corner of the loft. Francka brought some bread and a couple of large onions, and from that time, one square inch of stale bread and a thin slice of onion became our steady diet, only occasionally interrupted by stew or soup when one group of soldiers moved out and the next hadn’t arrived yet.

Our landlady had to be infinitely careful. It wouldn’t do for her to be seen by her neighbours climbing up the ladder carrying a dish full of food, or descending with the pail that served us as a toilet. So we stayed hungry most of the time, and the pail stood full and foul-smelling beside us, overflowing as often as not.

Mice became our intimate friends. They, at least, were not starving. Ears of corn tied into bundles were fastened to the slats, hanging over our heads to dry. That is where our mice feasted, showering the remains on our faces. Little black crumbs adorned our bread and onions, covered our clothing and faces and many a time, a clumsy little mouse lost his foothold on the slippery corn, only to land on any part of one of us four silent refugees.

And we were certainly silent! More so than the mice, since they were free to rustle and to squeak, while the four of us were required to remain completely mute. It was only during a certain time of the day that we could crawl over to the pail. The sound we made while urinating was the loudest sound in that loft during our stay, and even this cost us plenty of anguish and fear.

Needless to say, the children in the house didn’t know we were there, and the German soldiers, forever puttering about in the tool shed and the yard, posed the greatest danger. The location of the house was also unfortunate: right in the centre of the village, directly across from the inn and the community centre, which became the German army headquarters. Constant danger taught us to sneeze without a sound and to read each other’s minds. Since Father was apt to snore in his sleep, we slept in shifts — first Mother, then me, then my little sister, Vera, stayed awake to poke him when he started to breathe heavily.

But all our precautions were insufficient to quell the fear of our benefactor, and for once, even money didn’t have its customary appeal. Old Havko came up as often as it was safe. He begged, pleaded, threatened and swore — all in a hoarse whisper — and we trembled with fear and despair lest any of his numerous threats materialized. The man was genuinely afraid. Prodded by his daughter and son-in-law, he was determined to get rid of us one way or another. There was the time when he came up carrying a pitchfork, and I was sure he meant to murder us with it. Another time, he came up drunk, determined to throw us off the loft.

But we had nowhere to go. When pleading and promises of money didn’t help, we simply refused to move, and Father explained over and over again that if we were found in his loft, Havko and his family would be shot with us. That silenced him for a short time at least.

The times when Havko was drunk got more frequent, and I had visions of the old man drinking in the inn and confiding his terrible secret to some pal over a beer. I could picture the friend, eager to ingratiate himself with the German authorities, knocking on the little wooden gate accompanied by two uniformed Germans. But that was where my vision stopped; my imagination wouldn’t go any further.

As fall turned into winter, the cold weather plagued us. Exposed to the wind from all sides, our thin blanket offered little protection, and we huddled together as close as we could to keep each other warm. When one of us wanted to turn and lie on the other side, we all turned, but only when we thought it was safe enough to make that much noise.

Then spring arrived. I could hear the children playing outside, and I longed to be there too. As the sun was melting the snow on the roof, water dripped in steadily through the straw covering. We weren’t bothered by being soaking wet. We were listening to the distant rumble of the battlefield drawing nearer and nearer.

When the battle was right upon us, we didn’t mind the shower of machine gun bullets that landed in the straw around us — this was freedom drawing nearer. As the village people rushed to their basements, in our attic loft we had the hope of liberation on our side. When the first Soviets found us, we were ready to greet them enthusiastically, but no sound came out of our mouths. We had no voices. It was days before we could talk even in hissing whispers, and weeks before we found our voices again.

Learning to walk again was another difficulty, especially for my young sister, who was then six years old. She had to be taught the technique of walking, of putting one foot in front of the other, and for weeks afterwards she was apt to stumble and fall, even on a straight stretch. We had spent seven months in that attic and were so happy to be free, but when we got back to our town, we found that everyone we knew was gone and all our belongings had disappeared. There was nothing to go back to.

Finding Our Footing

It’s still a mystery to me how our parents managed to get our lives together in Czechoslovakia after the war — to get tutors for me and my sister so we could catch up on the years of missed schooling, to arrange piano lessons for me and violin lessons for Vera, even just to find us a place to live. At first, we slept on the floor of a spare room at a friend of my father’s. I remember making trips to the railway station several times a week to meet the trains that brought survivors back from Germany and Poland. We took food and water to the sad group of travellers as we searched for family members or friends who might have survived. We did not have much luck with that. All of my father’s family perished — two brothers, their wives and children, a sister and her family. A few cousins from my mother’s large family found their way back. No one remained there for any length of time; everyone tried to escape the memories. It was heartbreaking to see one person from a large family return to their hometown in search of their kin and find no one.

I became active in Hashomer Hatzair, a Zionist youth movement, and wanted to make aliyah, immigrate to Israel, but my father insisted on keeping the family together after our ordeal, so we all waited for our permit to come to Canada. We managed to leave just before the Communists took over Czechoslovakia.

We were allowed to immigrate to Canada in 1948, on the condition that my father work on a farm for one year. The farm was in rural Ontario, near Guelph, in a place called Alma. The house we were taken to was old and rundown and had not been occupied in years. The doors did not shut properly, and the windows would not open. There was a woodstove on the ground floor and a long thick pipe ran from it through the upstairs bedrooms without bringing them any heat. We didn’t use those bedrooms because we had no beds, only a couple of old mattresses, and because it was too cold up there. The house was overrun by mice but we could not resent them too much — after all, they had been there before us.

One memory my mother recalled from that time was of a dark, cold winter evening. There was a knock on the window. We were surprised, since we knew no one who lived nearby. Anxiously, she asked, “Who is there?” The answer that came was, “Eydn fun der gegnt” (Jews from the area). A Jewish family from Palmerston, a town about thirty kilometres away, had heard we were there and had come to visit. They brought us some furniture and other necessities, and they became our friends. Their last name was Wald and our family will always be grateful for their kindness.

My father’s salary was too small to live on, so my mother did housework for the farmer’s wife to supplement our income. She cleaned and ironed, and was paid in turnips, cabbages or potatoes. The farmer’s children were cruel to her, kicking or pushing her as they passed by. The son used to yell at us that he would set our house on fire. Surprisingly, these conditions did not depress us. On the contrary, we laughed a lot during the months we spent there. In spite of the poverty, isolation, hard work and the coldest winter we had ever experienced, we found so much to laugh about. We considered our situation to be an adventure, a new beginning and definitely temporary — a step on the way to a new and better life. Our stay at that farm ended about six months later, when my mother became pregnant and was feeling ill. The farmer, afraid that she might die there, fired my father. She did not die, although she lost the baby. We went on to another farm and ahead to our new life in the New World.