Peter Nesselroth

Born: Berlin, Germany, 1935

Wartime experience: Escape, hiding

Writing partner: Brenda Cowen

Peter Nesselroth was born in Berlin, Germany, in 1935. In 1938, soon after the Kristallnacht pogrom, Peter and his parents fled to Antwerp, Belgium.

In early 1941, they, along with thousands of other Jews, were expelled from Antwerp and sent to live in Limburg, a Flemish province in Belgium, for nine months. In the spring of 1942, as Belgium Jews were being deported to Nazi camps, the family left for Brussels, where they began to live in hiding. In early 1944, their hiding place was betrayed, and they were taken to the Gestapo headquarters for interrogation. Peter, who had an ear infection, was transferred to a hospital for Jewish children in Brussels. His parents, however, were deported — first to Malines, a transit camp, and then to Auschwitz-Birkenau. During his hospital stay, Peter was retrieved by relatives, who soon smuggled him into Switzerland for safety. There, he lived with a foster family in a village near the Jura Mountains. After the war, Peter was reunited with his mother; his father had been killed in the camps. Peter, his mother and his uncle immigrated to New York in 1950, where Peter earned his BA and PhD. He married in 1961, was divorced, and remarried in 1966. In 1969, Peter and his wife, Carolyn, moved to Toronto, where Peter had been offered a position at the University of Toronto. Peter and Carolyn raised a family in Toronto, and Peter had a successful academic career, teaching French language and literature as well as comparative literature, directing the department until his retirement as Distinguished Professor Emeritus in 1998. Peter Nesselroth passed away in 2020.

Pressure Builds

I was born in Berlin on March 1, 1935. My middle name, William, was after my maternal grandfather, William Messow, who was an anglophile, and not, as people think, after the German emperors Wilhelm. My father was born in Munich in 1905, and my mother in Berlin in the same year. My father’s name was Laslo, an Austro-Hungarian name, and my mother’s name, Gerda, was German. My parents were living the life of Berlin in the 1920s, by which I mean that they were living a “life is a cabaret” style of life. I found out about this much later, when researching my background. My father was a prominent fashion designer. Not quite Schiaparelli but very fashionable nonetheless, as fashion was a major industry in Germany at the time. On the side, he played the drums in a jazz band. My mother did not work outside the home. She had several miscarriages, but gave birth to me in 1935. Life might have been fun had I not been born in the wrong place, at the wrong time, into the wrong race.

From the time I was born until our flight to Belgium, we lived in a large Berlin apartment. The main language spoken at home was High German with a few words of Yiddish. My earliest memories of my parents were joyful, but I could also sense that things were getting tense and that pressure was building in the home.

My parents were not religious at all, though I do remember my uncle Max taking me to synagogue. On Oranienburger Strasse in Berlin, there was a famous synagogue, the Neue Synagoge, or New Synagogue, where observant Jews would go on the High Holidays. On a visit to Berlin in the 1990s, I was giving a series of lectures at Humboldt University and visited that synagogue with some friends and colleagues. I suddenly remembered seeing a set of stairs going up to the entrance of the temple. My uncle had tried to drag me into the synagogue up those stairs, but I didn’t want to go. I had a toy, fashionable at the time, a little wooden cane that children used to imitate old people, but someone at the synagogue didn’t want me to take that toy in with me. I started screaming and refused to enter. (This sudden recall of a forgotten memory is what literary scholars call a “Proustian moment.” It is a phenomenon that occurs when a sensory experience — a sight, a sound, a smell — suddenly brings up long-forgotten scenes or events.)

The world, as I found it in 1935, was not a very pleasant place. Family life was strained even before Kristallnacht and before the Nazis began their pogroms. I do remember other Jewish families in our neighbourhood and their children. I recall being taken to parks in a pram. We could still go to certain parks but not to others. I really wasn’t concerned about that. I didn’t often play with other Jewish children in the streets, but I was sometimes bullied by boys in very dapper Hitler Youth uniforms. I was very jealous that I didn’t have a uniform like theirs. I’ve seen them since in old newsreels of German youth blowing their trumpets and beating their drums. I am not sure how much I recall from that time and what I have acquired from watching the films of that period. However, I had a bad case of wanting to be them. For the life of me, I could not see why I should not have been part of all that pageantry.

At home and in the community, the atmosphere was increasingly gloomy. People were worried about relatives who had disappeared or who were taken away to prisons and other detention places (the death camps came later). I felt the tension and overheard family stories of individuals mysteriously disappearing. One of them was my aunt Betty, a cousin of one of my parents. She was married to an “Aryan” German and she mysteriously disappeared in a drowning accident. Although it was officially claimed that she had drowned, we knew that the man she had married had probably decided that it wasn’t good for his career to be married to a Jewish woman. Such incidents seemed to happen frequently.

Peter’s father, Laslo (far right), and his siblings. From left to right: Emil, Ida, Josef and Laslo. Berlin, Germany, 1921.

Peter’s parents and their friends. Peter’s father, Laslo, is second from the right, and his mother, Gerda, is third from the right. Berlin, Germany, 1930s.

Kristallnacht Brings Change

For Jews in Nazi Germany, the situation became ever more frightening, culminating in the Kristallnacht rampages on November 9 and 10, 1938. I was then almost four years old. I remember hearing the loud noise and the shouting of antisemitic slogans outside. I knew intuitively that something awful was happening and could see that my parents were extremely frightened. We stayed indoors for many days. My father and our whole family decided that it was time to get out of Germany. He decided to hire people smugglers to “pass” us into Belgium. I didn’t understand a lot about money or deals at that age, so I do not know the details. The days before we left were difficult. I can best describe the preparations for leaving as being both slow and fast. By slow, I’m referring to how long it took us to finally decide to leave and am reminded of a slang word that I only learned much later, Buffetjuden. In German, Buffet refers to the piece of furniture, otherwise known in English as a “credenza.” The Buffetjuden were Jews who did not want to flee the country because they did not want to leave their valuable furniture behind.

Then, abruptly, my parents decided that we had to leave quickly since the personal danger outweighed any other concerns. We left Berlin on New Year’s Eve 1938. The decision to leave on New Year’s Eve was made because the smugglers thought that it was safer since the border guards would not be as vigilant at that time. When it was time to leave, I had to get up in the middle of the night, dress quickly and go into the street with my parents. We travelled with a group of people, I think, initially by car. We arrived at a border town called Aachen, a city in western Germany, very close to the Belgian border. Crossings usually took place in the early mornings. We had to spend the night in a stable of a farmhouse. I didn’t like it at all. I don’t know if I cried or had fun, but the stable was full of hay, and I felt like Christ in the manger, on the flight into Egypt, although that may have been my later projection of the memory.

I don’t recall how, but the next day at dawn we crossed into Belgium, arriving in Antwerp on January 1, 1939. We met up with our relatives, Aunt Ruth and Uncle Max, who had already landed there because they had been wiser and had left Berlin before my parents did. Max tended to worry and had been right to do so. They helped us settle in, and we found an apartment in their building. Everyday life was fairly normal, at last. There was a large Jewish community in Belgium, which was prepared to help the refugees from Nazi territories. This close-knit community was built around the diamond trade and industry. The mood in the city was pleasant. My father could go out to buy food and Belgian chocolate and cigarettes. There were also many official refugee reception organizations with volunteers from the community who helped resettle new arrivals and who even offered some financial help.

***

Life in Antwerp was good until May 10, 1940. On that date, the Germans marched into the Low Countries. The Belgian army was totally unprepared. I recall seeing soldiers marching off to war from our windows — looking rather ridiculous because they were wearing house slippers!

Then the exodus from the cities began. A great many people fled Antwerp and other cities, not just the Jews. Everyone was trying to get out and head toward France. We became part of that group, hitching rides on trucks and walking. I don’t know how many of us there were. As we marched, German planes flew overhead dropping bombs, and I witnessed houses exploding upon impact.

At some point, the crowd on the march decided that there was no reason to keep on going to France because it was already being invaded too, so everybody went back home. We had been gone from Antwerp for a few days. During that time, the Germans had invaded most of Belgium, although it took eighteen days before Belgium officially surrendered. The Germans were actually friendly at first. I think that they had orders to be polite. I recall seeing them strolling around town in their sharp uniforms covered in medals and sitting at sidewalk tables. My parents would go to these cafés in the neighbourhood; the German officers would be there and would sometimes even engage them in cordial conversations. This amicable ambiance in the city gave us a false sense of security.

To give herself time to socialize with her friends, my mother would drop me off at a local cinema and buy one admission ticket, which was good for all day. I would go in, find a seat and watch wonderful Nazi propaganda films over and over again. I must have watched my all-time favourite — Hitlerjunge Quex, a 1933 youth recruiting film — at least a dozen times. I thus acquired a first-rate cinematic education. As I watched the weekly newsreels that reported the latest triumphs of the unstoppable German advances, I was, of course, rooting for the Nazi troops. I also developed a fine taste for Wagnerian music and soundtracks.

My father would play cards with his friends, also German Jewish refugees, instead of doing what he should have, queuing up at the American consulate and waiting for our visa to emigrate. He had letters from American cousins who were willing to sponsor us. My uncle Max did spend his days standing in that queue and ultimately obtained passage to the United States.

Between December 1940 and February 1941, about three thousand Jews from Antwerp were the object of massive expulsion and were deported to Limburg, a province in the Flemish region of Belgium. Documents indicate that, on the order of the German authority, hundreds of “Israelites” were sheltered in several villages in Limburg. One document indicates that the Jews lived there for several months as forced deportees. In 1941, they were authorized either to return to Antwerp or to settle in various communes of the kingdom, among which Brussels and Liège are named. They were sheltered in various houses and camps and could roam freely in the commune, but they were not allowed to leave it.

In January 1941 we ended up in a village named As, which at the time was written as “Asch.” (I have since realized that many of the names of locations along my life’s path carried great significance.) We were placed with a local Flemish family. We lived there until everyone was told to go back to where they had come from. My parents and I returned to Antwerp on October 25, 1941.

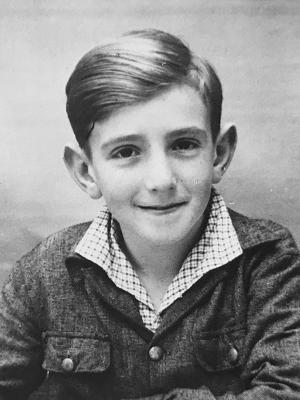

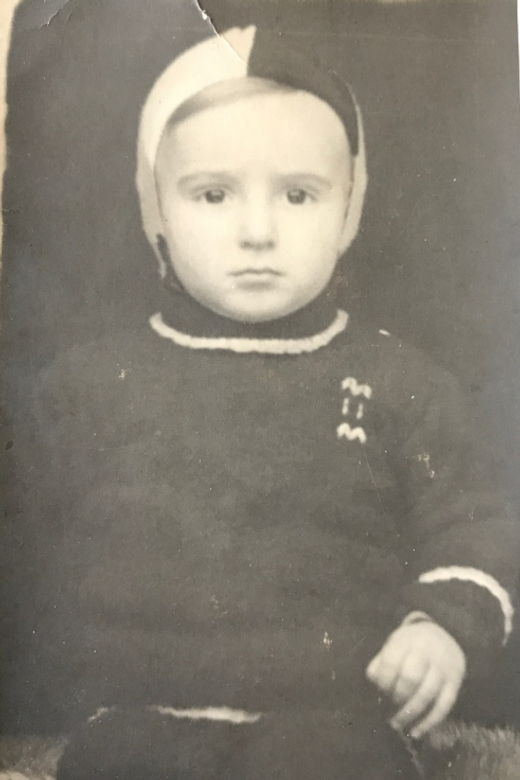

Peter at about one year old. Berlin, Germany, circa 1936.

Peter at about three years old. Antwerp, Belgium, circa 1938.

The day after we arrived at Gestapo headquarters, February 24, 1944, the Gestapo staff summoned a Jewish doctor who was working for them. He decided that an operation was urgent, so I was transferred from the Gestapo prison and taken to the hospital for Jewish children in Brussels.

Hiding, Passing and Escaping

In 1942, the situation in Antwerp changed dramatically. At the Wannsee Conference in a Berlin suburb on January 20, 1942, the Germans decided to crack down and make Europe as judenrein as possible, which meant killing all the Jewish “vermin.” The Nazis had many dictates, and judenrein was an overriding one.

That spring, my father decided that, for various reasons I did not understand, we must move elsewhere. The restrictions in Antwerp became more severe than in other Belgian cities, so we moved to Brussels. Somehow, whether by train or car, we managed to get to Brussels on April 27, 1942.

There, our life became radically different. We began to live in hiding, which meant that we did not officially register with the municipal authorities. We had an apartment over a café for a while, but as the search for hidden Jews became ever more intense and threatening, we had to move to another, supposedly more secure, apartment. By the time we moved to the second apartment, everyday life had become a genuine struggle. Jews were supposed to wear the yellow Star of David on their left lapels. In fact, I liked wearing that star because I didn’t view it as a sign of opprobrium but as a team insignia; it gave me a sense of identity, as the Jewish equivalent of a swastika pin or armband. One day, as I was walking along the street, a Belgian civilian, who was genuinely outraged by the fact that a child was forced to display this mark of condemnation, yelled at me to take it off. That man could have been killed on the spot for telling me to do so.

In our second Brussels apartment, we weren’t hidden by a family but were basically on our own. I don’t know how my father arranged it, but there was money being handed out from various benevolent sources to help. My father had been doing quite well operating some black-market activity between Berlin and Brussels with my uncle Joshi, who was still living in Berlin. However, that activity was discovered, and Joshi had to flee Berlin and joined us in Brussels. Part of the problem in Antwerp was the role of the Association des Juifs de Belgique, the Judenräte-like Jewish organization that had to report to the German authorities. The Germans kept tabs on the Jewish population in Nazi-occupied territories through these types of organizations. It is how they could follow whatever money was coming in from foreign sources. However, in Brussels the Jews seemed to have more independence from the German authorities. I do not know why.

Our hiding place in Brussels was located on the second or third floor of an ordinary building. It consisted of two rooms, and I think there was a bathroom on one of the other floors. On the main floor below our apartment, there was sort of a bordello, rooms where local girls and women entertained German soldiers. According to my mother, someone there must have denounced us or told the Germans that we were there. Supposedly, careless remarks made at these parties revealed the presence of hidden Jews in the building, leading to our arrest.

There were other hidden Jews in the building — a woman with her daughter, who I sometimes played with. I think that her name was Sophie. No father, no husband; he had been arrested before we moved in. I don’t remember much about them, except for the fact that they were arrested the same night we were.

Life in our apartment was very difficult, and being forced to hide there made me feel claustrophobic. Since I wasn't going to school, my parents and I did picture puzzles, and my father desperately tried to teach me how to read and write. Those were traumatic scenes because he was not trained to teach and got very impatient very quickly when I just couldn’t get it. I would get everything backwards.

Since I didn’t look particularly Jewish at the time, my parents would occasionally send me out to purchase necessities. They would dress me up with a cap like a Belgian boy, and I looked local. And at the time I spoke Flemish. Up until then in Antwerp, I had learned only Flemish, but in Brussels, I slowly began to understand and speak French as well. And so, I was sent out surreptitiously to do errands. Through the Jewish community, my father managed to get money. Then, whenever possible, one of us would go to get food or possibly someone brought it to us. The situation got progressively worse. Our food consisted mostly of tasteless cooked beetroots, leeks and yoghurt made from sour milk.

***

On the morning of February 22, 1944, I woke up with a terrible earache. The pain lasted all day, and my father decided that, despite the danger, he would get me to a doctor the next day. However, as fate would have it, in the early morning of February 23, there was a very loud knock on the door of the building, and the shouting of people running up the stairs. Two or three men in black leather coats pounded violently on the door. They almost broke it down. One of my parents got me dressed. We were not allowed to pack very much, just a few things. My parents were obedient and did as they were told. We were taken to the Gestapo headquarters in Brussels, which was known by the name of the street on which it was located, Avenue Louise. That was where people were taken, at least initially, and locked up in cages. When we arrived there, we were put in a cell that looked like an animal cage. I clearly remember that because the floors of the cages were slanted and slippery. The light was always on, and I could not sleep.

Here is what saved my life. My earache was caused by otitis, and the pain became unbearable. The day after we arrived at Gestapo headquarters, February 24, 1944, the Gestapo staff summoned a Jewish doctor who was working for them. He decided that an operation was urgent, so I was transferred from the Gestapo prison and taken to the hospital for Jewish children in Brussels. I later found out that it was official Nazi policy to separate children from their parents as quickly as possible to avoid hysterical reactions at the moment of separation. So I was released from the cellars of the Gestapo prison and taken to the hospital for Jewish children in Brussels. According to my mother, the order for this transfer was signed by none other than Adolf Eichmann. I was not able to verify this.

Before I was taken away, my father said goodbye to me. He shook my hand and that was that. My mother was within view, but I only remember my father shaking my hand. I knew that this was a very dramatic moment of interaction, but I didn’t know what was happening at the time. And I was still in pain from my earache.

When I arrived at the hospital, the doctor examined me and confirmed that I needed an operation. It took place the next morning, on February 26, 1944. I was wheeled into the centre of a ward lined with hospital beds. The doctor tried to put me to sleep with ether, which was terrible because it felt as if I were being choked. I couldn’t breathe until I fell asleep. After the operation, I woke up in one of the beds placed along the walls. I do not remember speaking to any other children at the hospital. I later discovered that the occupation authorities were gathering us there before deporting all the patients to death camps. My stay at the hospital lasted from February 25 to March 9, 1944. The severe earache had gotten me out of the Gestapo cellars, and it was kind relatives who would get me out of that doomed children’s hospital.

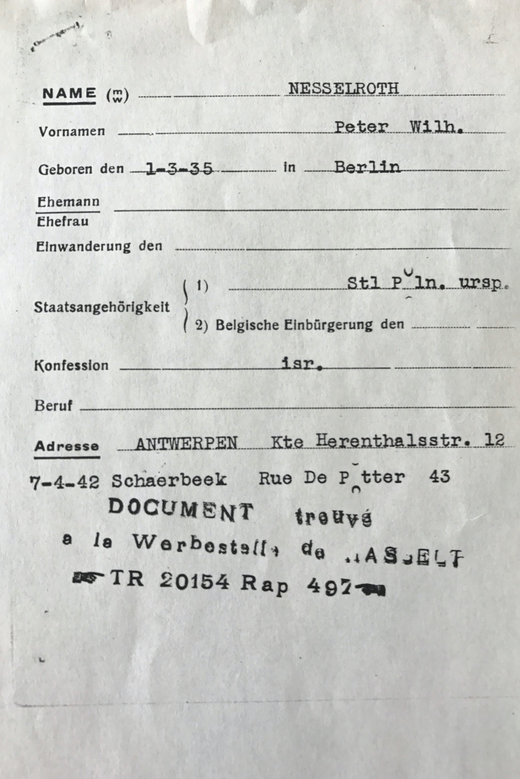

Peter’s German identification document, dated April 1942.

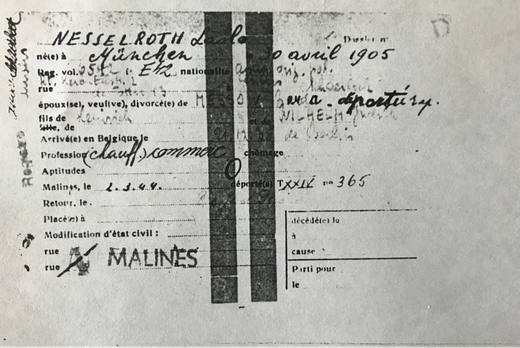

Transport documents of Peter’s parents, Laslo and Gerda Nesselroth, indicating that they were sent to Malines, Belgium, in March 1944.

Peter and his Sustaining Memories writing partner, Brenda Cowen. Toronto, 2017.