Andy Mayer

Born: Debrecen, Hungary, 1931

Wartime experience: Ghetto, forced labour

Writing partner: Linda Somers

Andy Mayer was born in Debrecen, Hungary, in 1931. After Germany invaded Hungary in March 1944, Andy and his immediate family — his father, stepmother and step-grandmother — were subjected to increasing anti-Jewish persecution.

That May, they were forced into the Debrecen ghettos and about one month later they were transported to Vienna, Austria. Andy and his family were sent as forced labourers to a nearby transit camp, where they worked at a cement factory until they were liberated in April 1945. On the difficult trip back to Hungary in May, Andy’s father was struck by a truck and passed away following the accident. Andy and his stepmother eventually returned to live in Debrecen, where Andy continued his education. In 1948, he immigrated to Canada as part of the Canadian War Orphans Project. He was eventually able to attend a business college and became a bookkeeper. Andy married Anne Seigel in 1952, and they raised a family in Toronto.

The Next Train

Although we felt the war in a lot of ways when it first started, we were not personally threatened; our lives were not yet threatened. There were new restrictions in Hungary, such as anti-Jewish laws, Jewish doctors not being able to practise on Christians. As a child, I didn’t notice them; I lived a sheltered life, but in 1944 everything changed and our problems started.

I had my bar mitzvah that year on March 18, and it was completely different from the way it’s done today. I was called up to the Torah and didn’t say my maftir, the final reading, despite that the fact I had studied, as it was the rabbi’s privilege to say it. I was disappointed. Afterwards, there was a big party, where I gave my speech to the whole congregation. My uncles had come from out of town for my bar mitzvah and almost couldn’t make it home because Jews weren’t allowed to take trains. They went home to their respective villages, but they might have survived if they had stayed in my city.

The day after my bar mitzvah, the Germans invaded Hungary because they didn’t trust the Hungarians to be their ally anymore. They marched into Budapest and came to Debrecen the next day. Adolf Eichmann came to Budapest, which I later read about extensively. He arrived with seventy or eighty officers and formed a Jewish Council in Budapest and eventually spread the order out to all the towns to form councils. Whatever Eichmann and the Nazi authorities wanted the Jews to do, they told the Budapest Jewish Council first, and then they informed the community that it was required by law, such as wearing the Star of David. We went to temple and brought whatever was demanded. The Jewish Council was the intermediary between the Germans and the Jewish population, which I think prevented the Jews from revolting or even thinking of resisting. Father was quite knowledgeable about a lot of things but wouldn’t tell me, a thirteen-year-old, what was happening.

Slowly, everything was taken from us, including our homes, stores, bicycles, cars and radios. The Germans came in March, and by June most of us were on our way to the Nazi camps.

In May, we were forced into ghettos that were located in already heavily populated Jewish districts in Debrecen. At the beginning, we were allowed to take some furniture, like a bedroom set; we were given one room to live in. Within three-to-four weeks, the authorities decided that everybody should be sent from the small ghetto where we were to the larger Debrecen ghetto. Then we had only suitcases with clothes and some food, and all ten thousand or so Jews were in the same ghetto.

A few weeks later, on June 20, we were given instructions that we were going to be transported to the outskirts of the city to the Serly brick factory, where they used to make bricks. The factory had railway lines to all the trains to transport the bricks. We were held there, waiting, for about seven days, and we slept outside on the ground. I remember public latrines with holes and a piece of wood. The only bit of shelter was where the bricks were dried outside to age after they came out of the oven.

The authorities loaded the trains under all kinds of pretexts. First, it was families that had more than four children who were “qualified” to go on the first train. All the people from different Orthodox and Conservative groups were told that if anybody held office, they were also qualified to go. There were rumours we were being sent to Palestine. People had no idea what was happening. My father did not qualify and was scared because the Hungarian police were taking prominent Jews every day and beating them to a pulp for their valuables. They were bringing them back at night all bloodied up, and my father said to us, “We better take the next train, as it cannot be worse than here. I’m afraid they will call my name tomorrow and then I’ll go for interrogation and they’ll beat me up.”

My father had decided for us, and we volunteered to go on the next train. We were not forced. My father, my stepmother, my step-grandmother and I got on these cattle cars, eighty people to a car, and we had to stand because there was no room to lie down. We were given a couple pails of water and bacon (on purpose), and pails for urine. We didn’t know where we were going; as I learned afterwards, we weren’t going far.

We spent two or three days locked up on the train. I don’t remember much but I do remember people screaming and that I had to stand up. My high school teachers were there, and one of them committed suicide by taking forty aspirins. He went to sleep and then he was gone. I wasn’t aware of what he and some of the others were doing, but I think my father was. After those days, we ended up in Vienna. We were unloaded and told to get out of the car, where the sick and dead people remained. This was the worst part of my wartime experience — I compared everything afterwards to it. I was especially affected by the death of my high school mathematics teacher, a grey-haired gentleman.

When we arrived in Vienna, we were put into a nearby transit camp; then, 120 of us were sent out to manufacture cement blocks. Compared to what happened on the train, this experience was nothing. We were shown how to make the cement blocks, and I helped to unload the raw material, slag, and make blocks. We stayed there for nine months. We were working as a family unit, with only one guard for 120 people. There was no fence, and we could have tried to escape, but there was nowhere to escape to. We were in Austria, among Germans who hated Jews, but they didn’t bother with us; they had Auschwitz and other death camps for that. I was thirteen years old and thought it was a great adventure, since I’d never been further from my hometown. We survived there until April 1945.

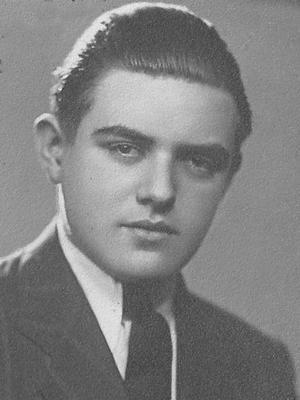

Andy at age ten. Debrecen, Hungary, 1941.

Andy, age six, with his mother, Bella Mayer (née Mandl). Debrecen, Hungary, 1937.

Andy’s stepmother, Piri Miklos, and his father, Mano Mayer. Debrecen, Hungary, 1942.

A New Environment

In April 1945, we heard guns as the Soviets were closing in on Vienna. The Germans were experiencing defeats every day. We left our workplace and hid in the nearby village in a wine cellar, waiting for the Soviets to overrun the village. The soldiers appeared within a few days, and we were liberated. We were told by a Yiddish-speaking officer not to stay there, but to start walking towards the next town because the front would move back and forth and we could face death if the Germans were to retake the village.

We walked from six in the morning until five at night. The elderly people with us couldn’t walk at all, so we acquired horse-drawn carriages and put our so-called luggage (shmattas, mere rags) on top, along with the elderly. We had no horses, so we used ropes to pull the carriage ourselves, as though we were horses, with others pushing them. Although the Soviet convoys in the area had ammunition and food, they weren’t a modern army, and they supplied the front lines by using these old-fashioned horses and carriages. When the soldiers saw us pulling these carriages like slaves, one motioned my father over and gave him a spare horse and hitching equipment. They had two extra horses, like they were spare tires. My father wasn’t a farmer, but somebody had to do it and we had to get going, so he hitched up the horse. I don’t remember if it was the first or second day, but there were some big American-made trucks on the road. We were on the side of the road, moving very slowly, and my father was holding the horse with the reins and leading him. These trucks were approaching quickly and the horse got scared and threw my father down in front of one of the trucks. He was struck by the truck and knocked down into a ditch and was hurt very badly. He had survived the war only to have that happen. The doctor from my hometown was in the next carriage and came over to help, but he said he couldn’t do anything for my father, and he walked away.

We made it to the next town in another few days, and then my father needed to be carried. We got some blankets on the way and broke into a warehouse where we found onions, which were treasures. We crossed the Austrian border within three-to-five days and got onto a freight train that was going to Budapest. We didn’t know if my father had broken bones and had no idea what was wrong. He was conscious but couldn’t move. My stepmother had a sister in Budapest who took us in and put him to bed with nice, clean white sheets. He wasn’t doing too badly, but when he lost consciousness, we took him to the Jewish hospital. He died there on May 12, 1945. According to a doctor in the hospital, his brain was inflamed and if he had received penicillin, he would have survived. He was buried in the Kozma Street Jewish Cemetery in Budapest in the section with the Martyrs’ Memorial to Jews who were killed during the war. My mother is buried in Debrecen.

After we buried my dad, we didn’t go back to my hometown until a year later, in June. Our home was occupied by other people, and my stepmother requested to get it back and also to have the store returned to her.

Life was not really that different from before the war. I had missed a year of schooling because of the deportation, so I went back to high school, where the government had arranged for a crash course for children who came back from the war, so I was able to catch up. Nobody from my previous class survived the war. I was in a new environment and didn’t know anybody. The other kids didn’t want to stay in Debrecen and went to displaced persons (DP) camps and others went to Sweden. My stepmother supported me, and after I passed that course, she transferred me to a high school of commerce where I spent three years. There were very few Jewish kids, but that didn’t matter to me because I just wanted to focus on learning. There were non-Jewish teachers at the school, and since religious instruction was compulsory I had to go to a rabbi one day a week.

After my course, my stepmother found out through word of mouth that Canada was taking in war orphans, but the United States wasn’t. I had relatives in Ohio, New York and California, who sent affidavits for me to come to America. My father had told me I had seventy cousins in the United States, and I had thought he was just telling me a story, but it was true. Unfortunately, I couldn’t get into the states because the quota system was in existence. My stepmother told me, “You’ll be a grandfather before you get a quota number and get accepted.” My stepmother took me to Budapest to see my cousin, a lawyer, but he said there was no chance I’d be accepted. He said, “Do like my children and leave Hungary and wait outside the United States.” My stepmother said she wanted me to go. She went to a local lawyer, who took out a map. He said, “There is almost nine thousand kilometres of border between the United States and Canada, and I’m told it should be no problem to cross it.”

I qualified to go to Canada as an orphan because my stepmother didn’t tell the authorities that she was supporting me. She said, “If you don’t like Canada, I’ll bring you home, but at least you can see the world.”

We spent two or three days locked up on the train. I don’t remember much but I do remember people screaming and that I had to stand up.

Finding My Own Way

I had changed my name from Endre (Andrew) to Andre when I thought I was going to Montreal. We left New York on an overnight train to Fort Erie, Ontario, and then to Toronto, arriving on a Sunday morning. People from the Jewish community met us at Union Station. I was the oldest at seventeen and the leader, as there were kids much younger than me. I’ll never forget going up Yonge Street at eight o’clock in the morning with three or four other kids — there wasn’t another soul on the streets. All the stores were closed, with maybe one restaurant open. The kids asked me where all the people were, and I had to give them an answer, so I said, “They are having an air raid drill and everybody is in the basement.” I distinctly remember being driven up to Dundas and Yonge and there were no signs, so anybody could do whatever they wanted. Toronto was dead on a Sunday morning in 1948!

We lived in an orphanage near Harbord Street and Bathurst Street, on Markham Street. The boys slept together in one large room with twelve beds. The Canadian Jewish Congress took over and found us jobs and homes. People expected orphans would be small kids, but we were older and some of us were tough. When I was told to take a drink of water, I wouldn’t do it, simply because I was told to. Eventually, they put us into private homes, and I ended up on Lakeview Avenue at Dundas and Ossington, with an elderly woman who was a widow.

I was disappointed because in Budapest we were told that we would be able to finish our schooling in Canada. When I mentioned school, no one seemed to understand what I was trying to tell them. I was told that we had to go to work. I worked a variety of low-paying jobs: at an automotive repair shop, as an apprentice in a jewellery shop and in a bowling alley setting up pins. It was not what I wanted to do. I often thought about my stepmother telling me I could come home if I was unhappy.

I went to my social worker at 150 Beverly Street every few weeks, but after six months I told her I wanted to go back to Hungary. I said, “I want you to deport me. If you don’t do it, I will go to Immigration and have myself deported.” They were flabbergasted. The social worker went to talk to her higher ups and said something like, “We’ve got a difficult one here. He’s almost a man, and liable to do it.” So they put their heads together and told me, “We don’t know your capabilities, so we’ll send you to have an IQ test.” Although I’d never done one before, I did very well on the test. I was told I couldn’t go back to high school because my English wasn’t good enough to catch up on the last year of high school and I would fail. There was no money to support me for a couple of years of schooling. The social workers said they would arrange a one-thousand-dollar scholarship for me, but that they would control the money to pay my schooling, room and board. They put me into Dominion Business College, a private school for Canadian kids who couldn’t pass high school. I couldn’t have cared less about that because this was what I wanted.

I passed the ten-month course in seven months. My English was not 100 per cent, but I could do assignments at my own speed. I remember that the guy in front of me took the full ten months to finish.

The school got me my first job, which was bookkeeping at a Jewish firm, and I worked there for three and a half years. It was remarkable — I was now making thirty dollars a week, which was much more than the sixteen to twenty dollars I had been making before. However, it was still not as much as my friends who worked on Spadina in the garment industry were making; they were getting one dollar an hour, which was forty dollars per week. I was happy, though. I was now rooming with a family, and the mother was a very good cook. I fell in love with her daughter, Anne Seigel. We got married in 1952, when I was twenty-one and she was eighteen.

***

My faith in Judaism and God was affected by the war. During the war, my father said, “The Haggadah has to be rewritten if we get out of this. It has to be rewritten about how we survived because our survival will be a bigger miracle than what happened in Egypt. They are killing us.” He also said that we should have gone to America in the 1930s.

I lost all my faith after the war and purposefully lost my tefillin, phylacteries. I gave up religion for many years, but that started to change after we had kids. I didn’t rediscover religion, but practised a bit for my children’s sake. The kids had to go to Hebrew school, and my wife decided we should go to synagogue. I had to put up a good show. I also never taught my kids Hungarian, my native language. They went to English school and Hebrew school. I figured that something didn’t add up — I had seen all that suffering as God watched and did nothing about it. I couldn’t put it together. We got married in a synagogue only because that’s the way my in-laws wanted it. To this day, I’m not even 50 per cent a believer, but I go to the synagogue for companionship and sometimes I force myself to practise so I can join the congregation. I come from an Orthodox background that is very dogmatic, but things have changed for me. I gravitated to Conservative, which was more convenient for my children. We don’t always know what to believe in, but the Holocaust killed religion for me. I saw religious people suffering, and it felt like God forgot to help them.