Lisa Summerfield

Born: Prague, Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic), 1928

Wartime experience: Ghetto and camps

Writing partner: Caroline O'Connor

Elizabeth (Lisa) Summerfield (née Margolius) was born in Prague, Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic), in 1928. In 1941, she and her parents and sister were transported to the Theresienstadt ghetto and concentration camp, where they were detained for close to three years.

They were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1944, where Lisa remained until she was sent to the Neugraben forced labour camp near Hamburg, Germany. Lisa worked cleaning ditches and bombed-out buildings for several months. In February 1945, she was sent to Bergen-Belsen and eventually liberated by the British Army in April 1945. Quite ill after the war, Lisa remained in a field hospital and at the Bergen-Belsen displaced persons camp before returning to Prague. In 1946, after learning that her parents and sister did not survive, Lisa immigrated to New York, where she had extended family, and then joined her aunt and uncle in Memphis, Tennessee. In Memphis, Lisa attended nursing school and met Ralph, whom she married in 1952 as they were on their way to a new life together in Canada. They settled in Toronto, where Lisa worked at Women’s College Hospital and in a doctor’s office, and together they raised a family. Lisa Summerfield passed away in 2023.

From Democracy to Annexation

Czechoslovakia was still a new country when I was born in 1928, having only been established as a democratic parliamentary republic ten years earlier. Our nation was proudly and optimistically based on what was believed to be the American model of a democratic republic: church and state were designated as separate, and freedom to worship was a constitutionally guaranteed right. One’s religious beliefs were not relevant to the state or, really, to one’s neighbours, employers or government officials at any level. Children of all faiths went to school together, and people from all religious backgrounds did business with each other and associated freely. Czechoslovakia was the only country in Central Europe to remain a parliamentary democracy from 1918 to 1938, and the Czechoslovak economy was one of the strongest in Europe after World War I.

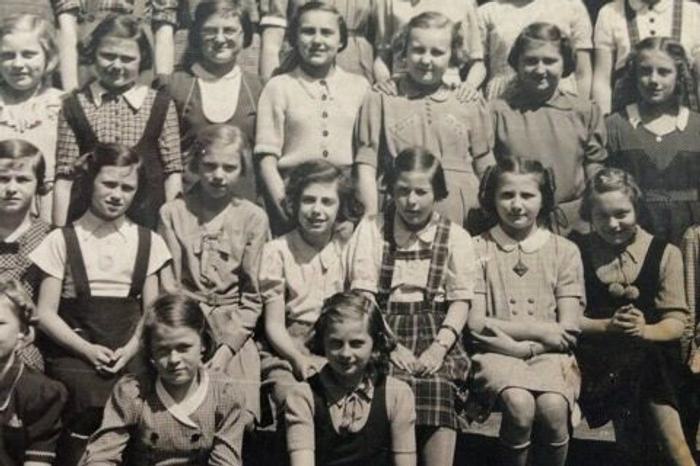

Of course, as a young child, I was unaware of any government. I also knew nothing of being Jewish. My parents were not observant, and I went to a public school with children who were mostly gentiles, although I had two or three Jewish classmates. I attended a public girls’ school; boys and girls were segregated at that time. I didn’t know who was Jewish and who was not among my classmates, only that some of my friends (mostly Catholics) went to church and believed in God, but my family did not.

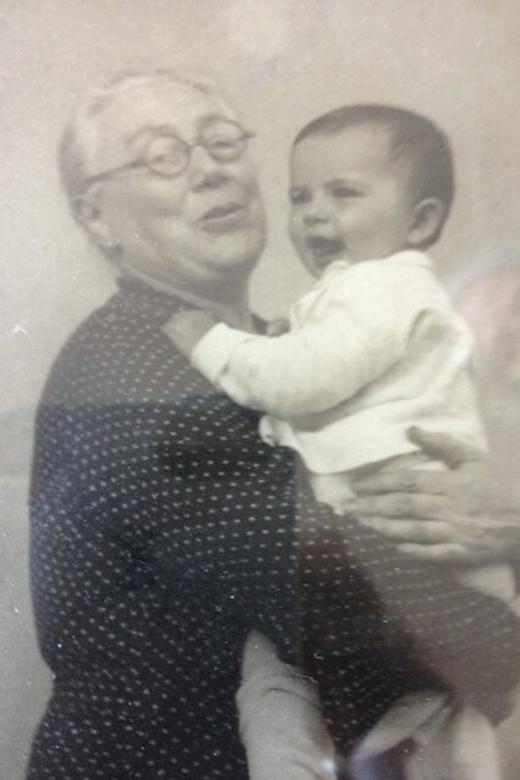

My sister, Helena, was born on January 6, 1932, when I was four. She was named after my mother’s sister Helen, and we always called my sister by that name — Helen. She was a beautiful, good-natured child with a sweet disposition, which provided a contrast to my strong, sometimes obstreperous personality. For the most part, I saw her as a nuisance, someone who tagged along when I went to see my friends and whom my mother insisted I include. If I went out to play or visit friends, my mother always told me to take my sister along, which I resented, so I wasn’t always nice to her. I remember an incident when the two of us were playing on a chair and Helen fell and hurt herself. She started to cry, and as my mother approached, I yelled, “It wasn’t my fault!” because I was sure I’d be blamed for pushing my sister off the chair.

As we grew older, the gap in our age mattered less, and Helen and I became close companions. We went almost everywhere together and generally got along quite well. After we were restricted from going to school or associating with non-Jews, our friendship was a welcome refuge. I remember us taking the bus together into town and speaking at length in a secret language that we’d invented ourselves. People around us always seemed to think we were foreigners, speaking a real language. Helen was such a sweet, agreeable girl, she never even complained to my parents when I was mean to her or bossed her around.

My parents were well-educated, proud people. My father was a banker and my mother had degrees from Charles University in both French and English language and literature. My mother saw herself as a modern European; she valued education and the arts while avoiding all association with religion or religious practice. She used to take me, and later Helen, on day trips to different churches and cathedrals in Prague, and she would make a point of telling us that she wanted us to admire the architecture of the buildings and the masterpieces of art and design within, not the doctrine of those who spoke from the pulpits. My mother was talented and artistic in many ways — she was good with crafts, knitting winter scarves, hats, and mittens for us.

My father was extremely loyal to his parents. I got the impression my mother believed we’d stayed in Czechoslovakia instead of emigrating — when emigration was still possible — because my father couldn’t bear to leave his parents. My father’s younger sister, Elsa, and her husband, Fred Brunner, had left for the United States in the mid-1930s, but my father remained, mostly because he could not abide the thought of his parents struggling alone in Prague with no family. As the situation in Europe became more dire for Jews, Elsa encouraged us to emigrate and wanted to sponsor us all, but my father didn’t come to the decision to leave until it was too late for us to get exit visas.

No one knew how terrible our lives would become in Czechoslovakia under the Nazis. Many people hesitated to abandon their country because doing so meant leaving their homes, their friends, their jobs, and all of their life savings. Departing for a new country with no money and no source of income seemed impossible. The Jews of Europe didn’t know how desperate their situation would become and that most of them would lose everything, including their lives.

At one point, my mother arranged to take my sister and me to Switzerland. I’m not sure when this was exactly, but it preceded the German invasion of and annexation of the Sudetenland in September and October 1938. We travelled by train from Prague, which was a big adventure for us. We were told that my father stayed behind in Czechoslovakia because he had to work. My parents feared there was going to be war with Germany, since Hitler was threatening to invade Czechoslovakia if Germany was not given control of the mostly German-speaking areas bordering the Reich. Many German Czechs supported such an annexation and the hope among those who did not support Hitler, including, of course the Jews, was that he would not declare war if his demands for the Sudetenland were met and that the rest of the country, including Prague, would be safe if Czechoslovakia just conceded these border territories.

After our arrival in Switzerland, my mother found accommodation in Lausanne and signed Helen and me up for school. I went with my mother when she registered us and thought the school was the most marvellous place imaginable for children. Nothing like the old-fashioned school we went to in Prague, this place looked the way schools look here in Canada, today — bright colours, big windows, picture books and toys. There were little chairs, children’s artwork and paintings on the walls, crayons on the little tables. I thought it was wonderful, and I wanted to go to that school right away.

However, before we even got settled my father called from Prague to say the Germans had annexed the Sudetenland, and it was safe for us to come home because war had been averted. So we went back — which was a mistake. Several months later, on March 15, 1939, German troops marched into Prague and my family’s nightmare began in earnest, with the Nazis occupying the rest of Czechoslovakia. It was clear that my father always felt guilty that he’d held us back from emigrating when my mother was so determined that we needed to leave Czechoslovakia and, later, Europe. He felt responsible for the misfortune that befell us under the Nazis, and I think he suffered silently for the rest of his life, feeling a terrible weight of responsibility and blaming himself for our fate.

The Occupation

Everything changed for us under German occupation. We had to give up our apartment because the Nazis wanted to use it. In late spring 1939, we moved from the area of Prague known as Letná to Nusle, a district of Prague farther from the centre of the city. It turned out to be fortunate that we were asked to move at that time, since a couple years later, in January 1941, Jews were forced out of their apartments in the best areas of Prague and moved into old tenements in a cramped, older part of the city (first, second and fifth districts). We were permitted to stay in the new apartment until my family was eventually arrested and deported.

I was quite happy to move to Nusle, where there were more trees and green spaces where my sister and I could play. Our old apartment building had been on a busy street where Helen and I weren’t allowed to go outside without supervision, but at the new place we had much more freedom. We ran around outside and played and enjoyed it there. I am sure that being forced to move was difficult for my parents, but they hid most of their worry and discomfort from us, protecting us from the real reasons we were required to make these changes. My father was prohibited from working at the bank and was reduced to supporting our family by doing hard manual labour, for which he was paid a pittance. He wasn’t suited to this type of work at all, and it must have been incredibly demoralizing for him to lose his livelihood, but as far as Helen and I knew, he just had a new job. My parents always went to great pains to make everything seem normal, as much as possible, to protect their children.

My mother was strong, practical, capable and determined to safeguard her family at all costs. If I asked her about what was happening to us, why we couldn’t go to school or shop in certain stores, she was very no-nonsense; she would always minimize whatever new restriction had been placed upon us and what the effect on our family would be. After our exclusion from Czech schools, a group of Jewish parents arranged for private tutoring in their apartments. Children of different ages went to different apartments for “school.” I went with two other girls and two boys my age for daily lessons from a young woman who’d married a Jewish man and so was no longer allowed to be enrolled in medical school. It had always been my ambition to go to medical school myself, so I remember thinking that it was too bad this girl couldn’t complete her studies just because her husband was Jewish. We had no books, really, and few supplies, but our parents and the teachers did their best, and our private lessons continued until we were deported.

Lisa (left) and her sister, Helen. Prague, 1938.

Lisa (second row, third from the right) in a school class photo before the war. On Lisa’s right is her friend Vera, who she kept in touch with after the war. Prague, date unknown.

Taking the Tram

The first transports of Czechoslovak Jews began in October 1941. About five thousand men, women and children were sent to the Lodz ghetto in Poland. My friend Vera was part of that transport. I think the deportation lists were compiled alphabetically, so my family wasn’t in that group because our name began with M. Most of those who went to Lodz ended up being transported directly to Auschwitz.

By the time my family was ordered to report for deportation, Czechoslovak Jews were being sent to Terezín, an army town, where a former army barracks had been converted into a ghetto and then camp called Theresienstadt. We were told we’d be able to stay together there. My parents were extremely anxious about the possibilities involving deportation, but they kept these fears from Helen and me. They were slightly reassured that we were going somewhere that was not in Poland, and where we’d be allowed to stay together.

We had friends, a Christian couple who had not been able to have children and who were fond of my sister, Helen. They wanted to keep Helen with them, as their daughter, so she wouldn’t have to be deported. However, my father decided against leaving my sister with them. He knew our family members’ names and ages were documented on official lists, which the Nazis were using for the transports, and reasoned that if we showed up without Helen, we’d be arrested — or shot — for trying to hide her from them. My father believed we needed to follow every regulation to the letter, never stepping out of line or giving the Nazis a reason to persecute us further. He always advised me to follow the rules: “Do what they say, do not get into trouble, because then they will make it worse for you.” I suppose he’d seen enough injustice that he realized Nazis would use the slightest provocation as a reason to abuse a Jew.

In December 1941, my parents were notified that we were to report to a stadium at the exhibition grounds in Prague, near Stromovka park. We were told we could bring one suitcase each and perhaps also a knapsack — only as much as we could carry. We had to take the tram, the streetcar, to this fairground, which was then on the outskirts of the city. No one was supposed to accompany us, but my uncle Ernie travelled as far as the fairgrounds with us. My aunt and uncle were still in Prague at the time, as they’d not yet received their deportation orders.

My mother packed our bags, mostly food and warm clothes, and I remember she made sure we all had good leather shoes; she had also made sweaters and scarves for all of us. My mother was talented with sewing and crafts, very good with her hands, and my sister was creative in that way as well. Helen could draw and paint and was always making little toys and things out of scraps, out of nothing. She was a tiny child, only nine years old and very small for her age, when we made that journey. We were all undernourished, but now, when I look back, I’m sure that on top of this Helen was unwell. Perhaps she had tuberculosis or something similar. She never had an appetite and was generally tired, although she always remained cheerful and good-natured, running around with her friends and playing. She just never seemed strong.

On the day of our deportation, as we approached the streetcar while carrying all of our luggage, it was obvious to anyone on the tram that we were Jews and where we were going. We climbed on, and as we were putting our fare into the box, the streetcar conductor looked at Helen and said to my mother, “She has to pay adult fare.” He was being cruel, for no reason other than spite, or antisemitism. Helen was only nine years old and looked much younger. She was obviously a child, who should pay only a child’s fare. This driver knew my mother couldn’t argue with him, so he demanded more money. He had all the power, and she had none.

My mother paid the adult fare for Helen and we slowly made our way to the very back of the second car, as required. As we sat down, my mother suddenly began to sob uncontrollably. It was as though all the heartbreak of our deportation had been encapsulated into this one moment of injustice, where the Czech tram driver not only didn’t care that we were being deported but wanted to make it worse for us. Helen and I were not used to seeing our mother cry; she’d always been the calm voice of practical reason in our family, but somehow this incident seemed to break her heart. When we saw her crying, we all started to cry as well.

My Uncle Ernie travelled with us as far as he could and then had to say goodbye and head back to Prague. It was a terrible, emotional day.

The fairgrounds were patrolled by armed Czech guards and surrounded by barbed-wire fences. We were detained there for three or four days awaiting our deportation. For the first time in my life, my parents were not able to protect me from the reality of our situation. We were treated like cattle, with no food, little water and only a long ditch dug on the side of the field in which to relieve ourselves. I remember being horrified at the idea of sitting and going to the washroom out in the open, in front of everyone. My mother had to take me to use this latrine, and she tried to help by standing in front of me to shield me as best as she could. We had to sleep on the ground; there were a few mattresses, but not nearly enough for everyone. Most of us had brought some food from home, so we ate that, but the environment was chaotic. People were panicked. It was a shocking experience for me. I remember being frightened.

The horrors of Auschwitz defy description.

Separated

At Theresienstadt my father worked doing some kind of manual labour — I am not sure exactly what, but I know he was part of a work crew that toiled long and hard for many hours every day. My mother had an office job, where she performed administrative duties. I think her job, as well as her quick thinking, probably saved our lives for a time. Because my mother’s employment at the Theresienstadt office was useful to the administrators of the camp, we were in one of the later groups sent to Auschwitz.

Every time there was a transport, the Germans had a list of a thousand names, as well as a second list with the names of perhaps twenty extra prisoners, in case anyone on the first list was ill and unable to travel, or died before they could be transported. The alternate list was included so the maximum number of prisoners would be sent on each transport. Again, the Nazis were notoriously efficient, checking and cross-checking their lists.

In spite of my mother’s job, my family had been on the list of alternates for the September 1943 transport, and when the guards first assembled the group that was to be deported, they included my family among those who were to line up to board the train. My mother was adamant, courageously speaking up when doing so meant she might be shot. She insisted that we would not go because there were people ahead of us on that list, who had to line up before we did. My mother refused to move into the line that was boarding the train; she demanded that the guards organizing the transport follow proper procedure. She stood up to the guard who ordered us to move along with this group, telling him we would not line up until all the people from the original list had proceeded ahead of us. The guard, a Czech, cuffed my father on the side of the head, but allowed us to wait until those ahead of us on the list were on the train.

The transport was filled, without us, using the first list; they reached the required number and didn’t have to include anyone on the alternate list. My mother’s strength of will and persistence kept us together as a family for one more winter at Theresienstadt, which probably saved us from death, for the time being at least.

But the following April, my family received the order that we were to be transported to Auschwitz, and we made the journey in May. Once again, we travelled by train, but this time it was a nightmare. The trip was three days long, and we were crammed into cattle cars with no food or water. Each car had one small window at the top for air, and we were given one bucket to use as a toilet. The people in our car organized themselves so the luggage was piled at one end and the children could climb on top of the pile, near the small opening, to get some fresh air. I remember sitting on top of the luggage, clinging to Helen and looking out the tiny window as the dull landscape rolled by. I know many didn’t survive that terrible journey, but no one in our car died.

We arrived at Auschwitz and were sent immediately to a family camp at Birkenau, to which all the people from Theresienstadt were initially deported. We were allowed to stay with our families, and the children were housed in a designated children’s building during the day while their parents went out to work.

The horrors of Auschwitz defy description. I still remember the terrible smell. We were forced out of bed at every day 4:30 a.m. and subjected to the gruelling ordeal of the Appell, the roll call, forced to stand in line for hours on end in rows of five while the Nazi soldiers counted us. We were not allowed to move or speak, and we lived in fear of arbitrary, harsh and sadistic punishments.

My mother did her best to shield Helen and me from our new reality, against all odds. When we got to Auschwitz, I heard a rumour that people were being gassed at this new camp, but when I mentioned this to my mother she told me not to be ridiculous, telling me that of course such a thing could not be true. I believed her.

My father was forced to do heavy labour, hard work like digging ditches and carrying loads of rocks in a quarry. He was physically exhausted, very ill and terribly depressed.

On June 17, 1944, my sixteenth birthday, there was an announcement that a selection would take place. During a selection, prisoners were forced to remove their clothes and run naked in front of Nazis, who would determine if the prisoners were fit enough to work, or if they seemed too weak. Those deemed “unfit” were often murdered.

We were told that only young women between the ages of sixteen and forty were eligible for this selection and that those chosen were being selected for work. My mother told me I should participate, that since it was my sixteenth birthday and they were asking for women aged sixteen and over, it was a sign that I should be in this group. “We won’t interfere with destiny,” was her verdict.

I think my mother believed the selection might give me a chance to get out of Auschwitz, and so I should take it. Perhaps she knew the fate that had met the prisoners who’d been sent to Auschwitz from Theresienstadt earlier that year, a fate that probably also awaited those of us who’d arrived more recently. Whatever her reason, she told me to go, so I did. My mother could almost certainly have participated with me in this selection, since she was forty-three at that time but could easily have passed for forty. As a relatively strong and healthy woman she would most likely have been chosen to go to the work camp with me. We’d only recently arrived at Auschwitz, so our physical condition, while poor, was not as desperate as many of the other prisoners’.

My mother didn’t go to the selection with me, even though she probably knew it was her best chance at survival, because, I believe, she knew my younger sister needed her and couldn’t bring herself to leave twelve-year-old Helen. She sent me and stayed to protect Helen.

I was selected to join the group of young women who eventually left Auschwitz for work detail, although at the time of our selection we didn’t know where we were going to be sent, when we were going to leave or what job we’d been selected to do. We stayed at Auschwitz for another few weeks with no idea when or if something was going to happen.

Then one day we heard an announcement that the women who’d been selected had to report for transport. The time to say goodbye had arrived. My mother asked me to repeat the information she’d told me to memorize in case I needed it after the war. I dutifully recited the name and address of the American couple who’d tried to help us immigrate: they lived on Union Street in Brooklyn, New York. Until our last moment together, my practical mother was thinking of ways to keep me strong, safe and protected.

My father gave me the advice he always offered and which I always followed: “Do everything that they say and do not break any rules. Blend in. Do not do anything that will get you into trouble.” My parents and Helen handed me what little food they had, in case I was facing another long journey. Giving up their bread meant they’d go without food until the next day. As I said goodbye, my mother started to cry, and I remember saying to her, “You promised me that you wouldn’t cry!” These were the last words I ever spoke to my mother.

***

We were led to a shower, where we had to get undressed and leave our old clothes on a bench; were sprayed with a disinfectant and shaved. I’d put my shoes beside my clothes and when I came out of the shower I noticed another woman had put them on. They were the good shoes my mother had chosen so carefully. I’d worn these shoes every day since I left Prague, and they’d lasted because they were such good quality. Those shoes were distinctive-looking, with diagonal stitching across the instep and a button near the toes. “Those are my shoes!” I exclaimed, pointing at them and looking up at the woman who was wearing them.

“Not anymore,” the woman replied. “Now they’re mine.” I was shocked that anyone would steal my shoes. For the first time in my life, I was going off without my parents. I felt unprotected and alone, in a world where people had to fend for themselves.

Lisa Summerfield, right, with her Sustaining Memories writing partner, Caroline O'Connor. Toronto, 2014.

Lisa and her husband, Ralph Summerfield. Place and date unknown.

A photo of Lisa in her apartment. Toronto, 2014.

On My Own

About two months into 1945, our forced labour camp near Hamburg was evacuated, and we were sent to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. I suppose the Allies were getting too close to Hamburg, and the Nazis were afraid we’d be liberated, so they moved us farther north. The journey took a few hours, and once again we were transported in cattle cars.

By the spring of 1945, Bergen-Belsen was hell on earth. Prisoners were being shipped there from other concentration and labour camps as the Allied forces moved in from all fronts. Almost sixty thousand prisoners were eventually held in a camp that, a few months earlier, had been crowded housing fifteen thousand. Everything was disorganized, there was no routine, no system for food distribution; chaos reigned. People were dying of typhoid fever, typhus, dysentery or plain deprivation. Dead bodies were everywhere. The stench was nauseating, overwhelming. In our barracks, three or four people had to share a single bunk and many were lying in their bunks covered in their own excrement, too weak to move. I became ill with typhus shortly after arriving; the disease spread like wildfire because of the overcrowding and unsanitary conditions. The suffering at Bergen-Belsen at that stage of the war was the greatest I had encountered, even worse than the terrible suffering I’d witnessed at Auschwitz.

We were all starving. I recall one day when I was walking, looking for some food, I saw an unguarded truck with a load of turnips in the back. I took a turnip and nothing happened. I couldn’t believe it. I later learned that the Germans had surrendered by this point — the British Army had liberated the camp on April 15.

The British soldiers drove through the camp in jeeps announcing in different languages that they’d arrived to liberate us, but asking us to stay where we were so they could get organized to provide for us. They tried to give us food, but many of the newly liberated died as a result. We’d been starved for so long that our digestive systems couldn’t handle the rich food, nor the quantities the British were offering.

I was weak and very ill with typhus and was taken to a makeshift field hospital located nearby, beside a converted soldiers’ barracks. Thousands of prisoners were sick and dying, and they had us laid out in rows, on stretchers, outside in a field, with a tent or a tarpaulin of some kind over top of us. I woke up several times, but no one was with me. I recall opening my eyes at one point and seeing a cup of tea on the table beside my cot, but I fell asleep again. Finally, I’m not sure how many days later, I was able to sit up a little and managed to drink a sip of tea. It occurred to me then that I might live. That sip of tea was my first small step on the road to recovery.

***

I began the long process of applying to the United States for immigration; the name and address my mother had made me memorize was instrumental in helping me to contact my father’s sister. The name I’d committed to memory was that of a distant relative, Fanny, and her husband, Joe, who lived, as I’ve said, on Union Street in Brooklyn. I sent Fanny a telegram, and through her, it reached my only other living relatives, Elsa and Fred Brunner. Apparently, everyone started to cry when they got my message; they knew that if the only word they were getting from Europe was from a sixteen-year-old niece, it must mean that everyone else — my parents, my grandparents, my uncles and aunts — had died in the camps. Shortly after I contacted Fanny, Elsa got in touch with me and started to make arrangements to sponsor me so I could go to the United States.

The immigration process was slow and was complicated by the fact that, on some of his identification paperwork, my father had declared himself as German rather than Jewish or Czech. This designation was automatically passed down to me, and I had to spend a good deal of time and effort to clear everything up so I could get a Czech passport and immigrate to the US. It’s interesting to note that my parents spoke German and had, to some extent, felt affiliated with Germany before the war. Germany’s complete betrayal of the thousands of Jewish people who spoke German and identified culturally with Germany was something my father could never have anticipated or fully comprehended until it was too late for us. After the war, any association with the Germans was negative, an embarrassment.

While I waited for my travel arrangements to be finalized, I attended school and tried to re-establish myself as a normal person with a normal life. Most people didn’t want to speak about what had happened in the camps. Those who’d been imprisoned wanted to move on and forget the ordeal they’d suffered, and those who hadn’t been there didn’t want to hear about what had happened. I learned to put my wartime experiences in a private place in my memory, a place I didn’t share with other people. Those who knew what I’d been through, those who’d been through it with me, were gone. The new people in my life found it too painful to think about or talk about what had happened to me.

***

Aunt Elsa and Uncle Fred had given me strict instructions that when I arrived in Memphis I was not to mention the fact that I was Jewish to anyone. I wasn’t observant, but as far as Elsa and Fred were concerned, in their new life I wasn’t even to admit my heritage was Jewish or that my family had been imprisoned in concentration camps because we were Jews. I was, my aunt told me, to tell everyone that I was a Czech Protestant and that I had been in a concentration camp because of my father’s political beliefs. No one in Memphis knew that my Aunt Elsa and Uncle Fred were Jews; they went to the Methodist church every Sunday and had tried their best to erase their Jewish past. I was not to threaten their new identity, and I was instructed to leave the past behind and embrace my new life as a secular American of Protestant heritage.

My aunt and uncle weren’t alone in their fear of being Jewish. After experiencing and witnessing such horror, many survivors and their families sought to eradicate their connection to Judaism. In their minds, to identify as a Jew was a frightening thing that could very well lead to their persecution or death. Elsa and Fred were only able to be truthful about their heritage many years after their arrival in the United States, once they’d established themselves financially and socially and felt safe.

Before I got to Memphis, there was a news article in one of the papers there about my upcoming arrival. It detailed the “political prisoner” story, and several young men, including one Czech who was lonely for the country of his birth and wanted to meet someone with whom he could speak his first language, contacted my aunt in order to meet me. I was a bit of a young celebrity in Memphis! After the war, many immigrants moved to places like New York City or Boston when they came to the United States, but not so many chose Memphis, and people there were fascinated by my story and my exotic foreign experience. But, even so, if I mentioned what had happened to me in the war, no one wanted to listen, so I soon learned not to mention it. Once again, I didn’t feel I could talk about my wartime experiences with anyone, nor, really, did I want to. I was happy to put it behind me.

Eventually, I even had my tattoo, which I’d received upon arrival at Auschwitz, removed by a plastic surgeon. Memphis was hot, and all the young women wore short-sleeved dresses and blouses. My tattoo seemed very dark and visible, and I was self-conscious about it. It seemed to me that everyone asked me about it every time I was out somewhere. I felt embarrassed talking about the concentration camps and I wanted that vivid reminder to disappear, so I looked up a plastic surgeon and saved my wages to pay him, but in the end, he refused to take any payment for removing it. I wish now, though, that I’d kept the tattoo. It would be a small physical reminder of my ordeal, something that would bear witness, for my grandchildren to see to help them understand that the Nazis were not ancient history but a product of the modern era. I still remember the number that was burned onto my arm: A307. In its place I now have an almost-invisible scar, and several emotional scars that will never disappear.