George Scott was born in Budapest, Hungary, in 1930. When George was a year old, his father passed away, and when he was six, his mother was taken to the hospital, admitted for severe depression.

George lived in the village of Szűcsi with his grandparents until age nine, when he was sent to a Jewish orphanage in Budapest. In April 1944, after trying to escape German-occupied Hungary for Slovakia, George was caught and returned to Sárvár, Hungary, where he was held in an internment camp. In August 1944, he was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. In November, George was sent on a transport to the Kaufering subcamp of the Dachau concentration camp. A few months later, he was moved to the Landsberg forced labour camp, and he eventually ended up in the main camp of Dachau, from where he was liberated in April 1945. After living in the Feldafing displaced persons camp, George returned to the orphanage in Budapest. In 1947, he went back to Germany, and he immigrated to Canada in 1948 as a war orphan, settling first in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia, and then moving to Montreal before settling down in Toronto. George worked at Ontario Hydro, married and raised a family. George writes poetry and has dedicated much of his time to Holocaust education.

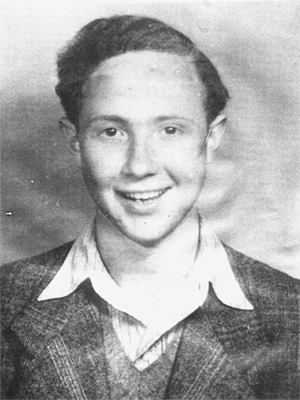

Photo above courtesy of Crestwood Oral History Project

Early Losses

I was one year old in 1931 when my father died. Apparently, he’d developed a stomach condition while he was a prisoner of war in a Russian gulag during World War I, and this eventually resulted in internal bleeding from a perforation. He was dead on arrival at the hospital in Budapest. I do have a picture of him on my wall, with my mother expecting, but I have no recollection of him beyond the stories I’ve been told. Reportedly, when he’d return home at the end of the day, he’d lean over my crib, and I’d grab his long black hair and pull myself up in the crib, holding on to his hair. In the pictures I have, I see my son Martin’s resemblance to him. After my father’s untimely death, Mom and I also returned home to the farm and the village of Szűcsi.

It’s painful for me to reconstruct these distant times. I was still a very young child, and a clinger. I loved my mother dearly. Sleep was an activity I abhorred because I was afraid I might miss something, and at bedtime my mother read me fairy tales that distracted and fascinated me. But increasingly, I sensed my mom’s unhappiness, and this made me even more needy. I nagged, cried a great deal and held on to my mother in the midst of a deteriorating, unhappy situation. Grandpa Mondi was the undisputed lord of the manor. There were lots of arguments in the house, which my mom always lost. Eventually, her loneliness and unhappiness claimed her.

I remember being in my Grade 2 classroom when someone came running to the school to tell everyone that my mother had been taken to the hospital in Gyöngyös, a town about fifteen kilometres from us. She had severe depression. I was only six years old, and my world came crashing down. My only close ally with whom I could identify was gone.

After my mother was admitted to the hospital, I was extremely sad. In one picture of me with my aunt Margo and cousin Laci, I look quite despondent. I was jealous that Laci had his mother, and I didn’t have mine.

My mother remained in hospital until the Germans occupied Hungary in March of 1944. I was only able to visit her once. Within months of occupation, the Hungarian collaborators forced all Jews from small towns and villages into ghettos. Hospitals, old-age homes and all Jewish homes were emptied. My mom was taken to the Hatvan ghetto and from there, around June 1944, deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau with the rest of my family. End of the saga, almost.

While my mother was still in hospital and I was in school, I spent more and more time on my own. The skill of escaping came to me before I understood what I was doing. The magic spaces of the farm — haystacks, lilac bushes, chestnut trees, rooftops, abandoned wells, slow-crawling June bugs, gentle raindrops — readily shared their secrets with me, as I shared mine with them. I got into all kinds of mischief looking for fancy bird eggs in the old wells, climbing every tree on our land, having repeat encounters with poison ivy. Many of my adventures resulted in injuries, scrapes and endless crying. Ilona, my wonderful grandmother, was always there for me. I remember the soft place under her double chin. I loved to kiss her there! She was the mother I had because my real mother was in the hospital.

My grandfather was not an easy man to share life or raise a family with — proud and quick tempered — but he had a good heart. He was always honourable, but forever seeking to prove he was right, convinced he was speaking for God. He dispensed “justice” readily, as he saw fit, and just as frequently, my grandmother tried to save him from the consequences of his actions. But sometimes we had fun together. I remember Grandpa Mondi playing “buttons” on the ground with me and carving a spinner for me for Hanukah. I can still see the blue ink marks left on his face when he licked his indelible pencil to put the Hebrew letters on each side of the spinner. On rare summer evenings we held hands and sang as we walked together. I still remember how the wheel ruts in the old dirt country roads came up to my knees. Grandpa Mondi had a fierce red mustache and blue eyes, and he was very strong. He bragged that he could pick up one hundred kilograms of grain — with his teeth — when he was young.

Even spending much time on my own, I did have friends, especially a boy the same age as me, named Joseph Maksa, who lived across the road from us. We still correspond. We still like each other. Is this not lucky? Is this not a miracle? It’s very important for us all to have good friends, to have the give-and-take of relationships. This was even more important for me — an orphan being raised by his grandparents.

As a result of my experiences, it cannot be a surprise that I became a reflective, quiet boy puzzled by many things. My early audience consisted of roosters, bushes, treetops, things that moved and made noises. I often cried into my pillow…and tried to talk to God. I quaked in fear and hid under the covers, out of sight of my grandfather’s two Sefer Torahs. I feared that God would punish me if I did something wrong or said His name in vain.

In school there were religious teachings, including Catholic catechisms, and the teachers often referred to the Children of Israel, but it wasn’t until later that I realized the Children of Israel meant the Jewish people. When I finished Grade 4, the highest grade offered in the village of Szűcsi, my grandparents placed me in a Jewish orphanage in Budapest. I was nine years old.

Escape and Capture

As time went on, a few new boys arrived at the orphanage. They came from Poland or from Slovakia. Somehow, they had escaped the German occupations and were placed with us. They spoke only Yiddish, and we could not believe the stories they told. One of these boys, Farkas, was from Slovakia, but spoke a bit of Hungarian. Although he was seventeen and I was only fourteen, we became friends and I idolized him. He was a brave boy.

When the Germans occupied Hungary in March 1944, we began talking about running away together. Farkas reasoned that all the Jews in Slovakia were killed, so we would be safe there — also, we could join the partisans! He claimed he knew where and how we could slip across the border. This was heady stuff for a frightened fourteen-year-old wanting to put on a brave face. Soon after the German tanks and trucks rolled into Budapest, stringent regulations were put into place against the Jews. We could no longer attend school, we had to wear a yellow star on the left breast of our jackets to indicate to all that we were Jewish, and at some point we could only go outside of the building between 10:00 a.m. and 2:00 p.m. to do necessary shopping. Farkas and I decided to make our move.

It was exciting. No one knew about our plans. One morning in late April 1944, I put on my jacket, no star, and we just walked out of the building. We took the streetcar to the southern rail station of Budapest, purchased tickets and got on the train we needed. Nobody stopped us or questioned us. I remember it was an intense four- or five-hour journey. We hardly spoke, so preoccupied were we with our own thoughts. We got off at a small station, I still don’t know where, and Farkas took the lead on a country dirt road. In half an hour or so, we came upon a post. We saw it from a distance, but the people inside saw us too. We kept walking toward it, and as we approached the shack, we could see there were two or three Hungarian soldiers, who soon came out and asked us for our papers. We had none. We were asked to wait. A truck arrived within twenty minutes and took us back to the village where we had gotten off the train. We were locked up in an empty house that must have belonged to Jewish people because I found a stack of Hebrew prayer books on a windowsill. I remember getting strangely emotional as I turned the pages. Farkas and I never discussed what had gone wrong with our plan.

We were kept in this house for a week or so. Food was brought regularly, but we were locked in, until one morning a policeman arrived, handcuffed us and marched us to the railroad station. It was a very strange feeling to be handcuffed. We were a sight, I am sure, as we stood in the station waiting room. A small crowd had gathered to discuss the happenings, and a woman pointed at me saying, “He does not look Jewish!” As I returned her glance, she looked away from me.

Today, whenever I speak to an audience, I refer to this incident, for I still find it very painful that she would not look at me.

Over the following days, the policeman took Farkas and me off the train at different stations and put us in various prisons. I had no idea where any of these stops were. A week or so into our imprisoned travels, at one of the larger stations, Farkas asked to go to the bathroom. He disappeared into the crowd and I never saw him again. When I returned to the orphanage in September 1945, I heard that he had managed to get back to the orphanage and that he may have immigrated to Israel. I hope this is true.

The policeman and I arrived in the town of Sárvár, in northwest Hungary. We walked through a big, guarded gate in a high brick wall surrounding a large building. Inside the wall, there were perhaps a thousand people — few women, mostly men, practically no children. After some time there, a few people who had read the newspapers told me that the Normandy invasion was in progress. No one seemed worried. There were rumours we would be taken east, to work in different locations, which I thought sounded okay. We were fed and allowed to loaf about all day, but we could not leave. I looked around for kids my age but found none. I still wanted to run away.

We were housed in a four-storey flat-roofed building until one morning in early August when bells started ringing and everyone was ordered to take their belongings and gather outside in the square. Something was happening! But I had other ideas. I ran up to the roof of the building, hid behind a chimney and watched the people lining up, talking, carrying their belongings. Everyone appeared relaxed, conversing with one another, almost relieved there was some activity.

In the midst of my reverie, the door to the roof suddenly sprung open and my heart jumped into my throat. In front of me stood a young man, maybe thirty years old, black leather jacket, civilian clothes, slim, about five feet nine inches tall. He had shiny black hair that was pasted flat to his head. As I cowered, his stern face transformed with a big grin. Not one word was spoken between us. I descended from the roof like the proverbial bat out of hell, ran out and lined up with the others.

We were all marched out of the square, five to a line, all accounted for. We proceeded to the side of the Sárvár railway station where a long train of cattle cars stood. There was no tension, just quiet conversation. But change hung in the air. There were two planks, side by side, reaching from the ground to each gaping wagon door. We started walking up and were counted as we entered. When it was my turn, I found that all the corners of the wagon had been taken, leaving me stooping on the floor in the centre of the car. A rectangular barred window in front of me showed a patch of reassuring blue sky. We were squeezed in tight before the big steel doors were slid shut. Like a receding echo, the sound of doors closing along the length of the train seemed to be the only thing I heard, until the last one was sealed. There was a shudder, and the train started moving. I became aware of the clamour and noise inside our wagon just as it began to subside. Very soon, there was no conversation at all. I realized there was a pail beside me, to be used as a toilet. In no time it was overflowing.

During the next two or three days our train only stopped once, in a field. People scrambled out to relieve themselves, guards with guns at the ready everywhere.

Auschwitz-Birkenau

On a bright summer day, we arrived at a very large complex and our train came to a sudden halt. The doors slid open to a scene of bedlam — dogs barking, men in blue-and-white-striped uniforms shouting. An announcement blared repeatedly over loudspeakers: “Leave everything in your wagons. Your belongings will be brought to your quarters!” Amid the shouting and commotion, people scrambled out of the wagons. Soldiers stood around directing everyone into lines — men and boys to one side, women to another, mothers with children in a line of their own. The lines formed at a surprising pace and drifted forward toward one German officer, some hundred feet ahead, who was checking everyone out. He was calm, absorbed, immaculately dressed. I later learned that this might have been Dr. Mengele.

I was very hungry. Scrambling out of the wagon, I saw a wonderful bright sky and, on the other side of our train, what looked like a soccer field with white goal posts, the gate through which the train had arrived. I remember that it felt reassuring to have arrived somewhere. I was happy to move my limbs, to observe the proceedings. It looked like we would be treated with some civility. In the group of all males, I moved along toward the elegantly dressed, entirely unthreatening man in the shining German uniform, who was fully absorbed in his task. When I reached him, I pulled myself to my full height, looking him straight in the face. He returned my look. Our eyes were locked for a second or two as he motioned with his hand for me to move left. “Working Material” went to the left, all others to the right. On the right stood a large, seemingly submerged building. After double right turns, the lines going that way were beyond our view.

Inside, on the walls, in all European languages:

“REMEMBER WHERE YOU LEAVE YOUR CLOTHES!”

Double doors, ajar, reveal a gleaming, tiled shower room.

As I write these lines, a deep numbness, a heavy heart still takes my breath away.

People get undressed.

Again, I remember my grandmother’s beautiful long braided hair, how proudly she worked on it. I cannot forget how shy my grandfather was.

Everyone’s hair is cut off, for hygienic reasons. All the naked bodies move into the shower room. Families stay huddled together, wanting to protect each other’s nakedness.

Once all are inside, the doors hermetically seal, shut from the outside.

On cue, an SS officer drives up to the building on his motorcycle. He inserts a canister into a cavity located on the outside of one wall. As the canister slips into place, it is pierced. The SS man drives off.

Inside the shower room, no water comes from the showerheads.

Zyklon B gas rises.

PANDEMONIUM!

People scramble to climb higher, to get away from the killing, burning stench. They climb on top of each other. It takes them minutes to die.

When the windows open and the ventilators come on, there is always a pyramid-shaped pile of bodies.

The corpses are hosed down, valuables, gold teeth retrieved.

Turnaround time: 2 hours. Capacity: 6,000 persons per day.

I know the above from a person who worked in the Sonderkommando, who witnessed the above tasks. The Sonderkommando were killed periodically, to eliminate witnesses. Those sorting the victims’ belongings were, ironically, called the Kanada Kommando because the storage area was referred to as “Kanada,” an imagined land of plenty.

***

The three hundred or so of us who were sent left were directed to a bathing and disinfecting facility a few hundred feet away — two left turns, past fenced areas filled with bald people in blue-and-white-striped uniforms. We were shorn, showered, sprayed and issued the blue-and-white-striped pajamas and shoes with wooden soles. We were lined up again and marched into one of the fenced sections we had passed earlier. It was called the Gypsy Camp. We were informed by those already there that this was Birkenau, and that there were no more Gypsies. They had been gassed. They had been allowed to live with their families next to the Jewish men’s camp. The name of their area remained the Gypsy Camp, or Zigeunerlager as the Germans called it.

We could see about ten numbered blocks on each side of the road, one side even numbers, the other odd. I landed in Block 3. All blocks were the same size, with one small door, a concrete floor, a horizontal chimney in the middle of the floor and sections separated by posts. That was it. No water. We soon learned the only place we had water (cold) was in the latrines, which were in one of the blocks in the centre. The water was heavily chlorinated, and the block offered two rows of concrete “seats,” about eighty holes, twenty inches apart for serious bathroom needs, and a trough to urinate in. I never saw more than four people in there at a time.

The group of buildings making up the Gypsy Camp was surrounded by electrified wires with little signs warning, Hochspannung! (high voltage) and guard towers every hundred feet. As we moved into the camp there was much excitement. We were the news source. “What’s happening?” “Where did you come from?” “What’s new in the world?” We told the people about the Normandy invasion, that the Germans lost the war for sure. In exchange, we were filled in on our surroundings. To one side of our block was the “Twins” block, housing human fodder for medical experiments, and on the other side I recall there being a women’s camp, where the soccer field stood. Of course, there was no interaction between camps. The last block in the odd-numbered row, closest to the incoming trains, was the disinfection unit where, to my utter surprise, I learned the person in charge was Sandor Wohl, my grandmother’s oldest brother. And during this busy exchange of information, out of the blue, my great-uncle Sandor appeared. Speaking to others, he always referred to me as “my sister’s first grandson!” With him was his brother Henrik.

After greeting me with open arms, my relatives pointed out what had happened to those from the train who had been sent to the right. “See the square chimney with the flames coming out, that’s where all the other people in your transport are coming through.” This information was too much, too overpowering for me. My knees went weak. My mind stupefied. My previous feelings of assurance gave way to trepidation followed by glumness and imperceptible apathy. We melted away, each one of us into our own cocoon.

Ruth and George at their wedding. Toronto, 1954.

George Scott with his class in Budapest, 1947.

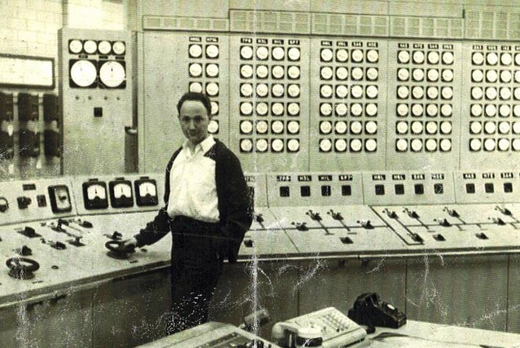

George working at Ontario Hydro as an electrical operator in training. Toronto, circa 1950s.

Like a receding echo, the sound of doors closing along the length of the train seemed to be the only thing I heard, until the last one was sealed.