Ed Herman

Born: Warsaw, Poland, 1931

Wartime experience: Ghetto, escape and hiding

Writing partner: Chris Dingman

Ed (né Emil or Emanuel) Herman was born in Warsaw, Poland, in 1931 and lived in Katowice during his childhood. In 1940, the Warsaw ghetto was built around his grandfather’s apartment building, where he and his family were staying.

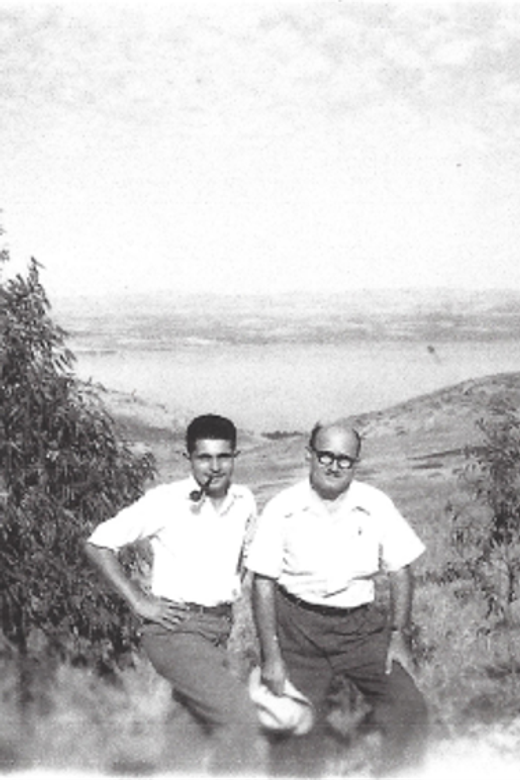

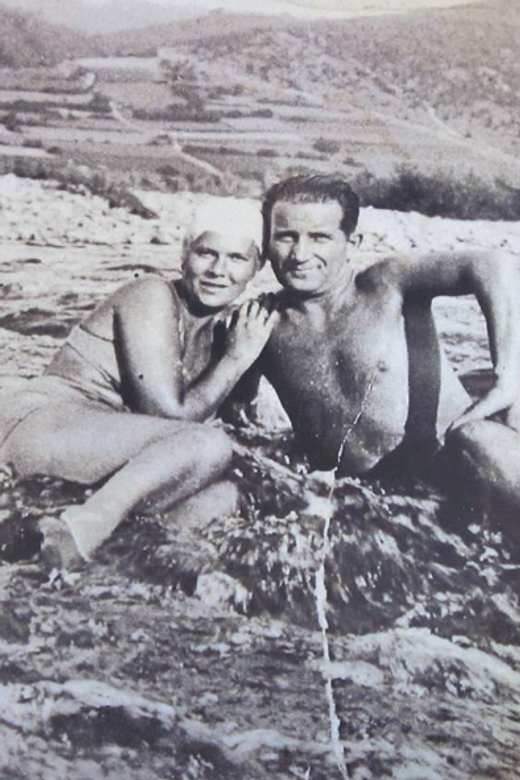

Ed escaped the ghetto with his family in the spring of 1942, hiding in towns and villages in the countryside. In September 1943, Ed was smuggled out of Poland without his family to Budapest, Hungary. He lived in an orphanage in Vác, Hungary, and then with his aunt and uncle in the countryside. Ed was liberated by Soviet soldiers in November 1944. He lived in Romania until he was reunited with his mother and sister in Hungary at the end of 1945. After spending time in displaced persons camps in Austria and Germany through 1946 and 1947, Ed joined his father in Israel in 1949. Ed arrived in Canada in 1954 and lived in Montreal, where he earned his BA, MA and PhD from McGill University despite having had only a first-grade education prior to the Holocaust. In 1961, Ed married Halina, a survivor from Poland, and they raised two children. In 1964, the family moved to the United States where Ed spent over forty years in academia as a professor of economics and authored numerous books. He and Halina are featured in the 2013 documentary film Never Forget to Lie. Ed and Halina Herman currently live in Florida, where Ed is active in Holocaust education.

The Beginning and End of My Education

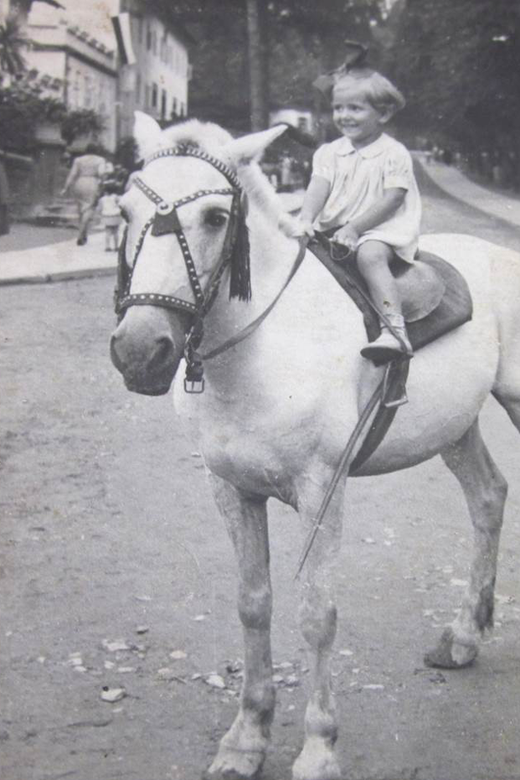

When I was six and a half, I started Grade 1 at the Polish Jewish school, and I loved it right away. School became extremely important to me, so much so that once when I was sick and my parents wanted to keep me at home I cried and carried on until they finally relented and took me to school.

As much as I loved it, my memories of school are vague, but I do recall my father taking me to the streetcar terminal where, most days, I caught the tram to get to school by myself. I remember him watching me as I got on, which was objectionable to me, because even then, at age six and a half, I considered myself too grown up and independent to require supervision. Seventy-two years later, when I returned to Katowice, I remembered the exact spot where I’d gotten on the streetcar to school all those years earlier.

At school I learned to read in Polish. Once we had learned the Polish alphabet, reading was easy — not nearly as difficult as learning to read English — and the first book I remember reading dealt with the religious holidays. What appealed to me most about the book was the part dealing with the concept of God and a supreme body, which became a tremendous comfort to me during the war. I loved to read, and by the end of the school year, I was devouring some serious books. At the conclusion of Grade 1, I received a graduation certificate, which I treasure to this day. At the time, I had no way of knowing that it marked the end of my formal education until more than fifteen years later.

There was a non-Jewish school across the street from the school I went to, and the Christian children sometimes threw stones at us and called us names. It was my first encounter with antisemitism, and I was not enchanted with it. I don’t remember exactly how I reacted, but I had, and still have, a tendency to tune things out, which I think has served me well over the years. My parents sometimes talked about antisemitism while we were living in Katowice, so it was clear to me that Jews were not particularly welcome there, but my family was very successful nevertheless.

My father was always proud of me. He made me very independent early in my life, which not only enabled me to survive but made me who I am. He also gave me a solid foundation and the self-confidence to know that, whatever happened, I would land on my feet. That confidence would prove essential in a surprisingly short time, and I know I couldn’t have managed the way I did without it. My mother was more in the background during my childhood, and I didn’t grow close to her until years later when I recognized her tremendous courage and came to appreciate what a superstar she really was.

My Mother’s Courage

Toward the end of August 1939, everything changed. There were all sorts of rumours about what was going on, and one day my father loaded us into the car and we left Katowice to visit my grandfather in Warsaw. I’d visited him when I was younger and liked him very much, so I was looking forward to seeing him. My father said we’d be back in two or three days, so I left all my toys and things behind, but that day turned out to be the last time I’d see our home for seventy-two years. It was the day I lost my childhood.

It felt like we drove for days, even though the distance was only about three hundred kilometres. We saw many refugees on the roads. The war hadn’t started yet, but within a couple of days of our arrival in Warsaw, Germany invaded Poland. It was September 1, 1939 — the beginning of World War II, during which over sixty million people died. Within the first few hours of the war, Katowice was taken as German territory and occupied by German troops. Because the city was so close to the German border, few Jews living there had a chance to escape the onslaught or to survive what was to come. To me, this was the beginning of the Holocaust. We learned later that one of the first things the Germans did after entering Katowice was burn the synagogue to the ground. While it was not the only building destroyed, much of the central part of the city was left basically intact.

In Warsaw, we initially spent more time in the bomb shelters than we did in my grandfather’s apartment. I vaguely remember many people, including some soldiers, crowded into small, dim spaces. The shelters were like musty basements and not the least bit comfortable. I recall leaning against my mother or my aunt to sleep. The bombings seemed endless, until suddenly it would become quiet and we knew we could leave the shelter and return to the apartment. It was such a relief to breathe the air outside.

My mother and sister were blond and looked gentile, so it was relatively safe for them to be out and about, enabling my mother to smuggle food into the ghetto for our family. I was darker than my mother and had very sad eyes because of everything going on around me, but I had a major advantage over other Jewish kids — I spoke Polish like a Pole. Our maids had taught me the language, so I had no hint of a Jewish accent; most other Jewish kids who’d learned Polish at home or school had tell-tale accents. Another advantage I had was that my nose was not a stereotypically Jewish-looking one. These sorts of things made a big difference during the war.

Money at that time was not much use, but we didn’t have many possessions to sell or trade because we’d only planned for a short visit to Warsaw. Fortunately, my mother had a little money and some jewellery that she had taken with her from Katowice, and she and her sister bought things like silk stockings and scarves and took them by train to different villages outside Warsaw, where they were in big demand. They’d trade the goods for food, which they brought back to us to supplement the rations we got; it was almost impossible to survive on just the rations. This travelling back and forth began before the ghetto was established and was initially relatively easy but became much more difficult after the walls went up. Then my mother had to leave by going through some bombed-out buildings. I remember going with her once, and although my memory of getting out and back into the ghetto is very selective, I’ll never forget being told to tell people that I was Christian, that if anyone challenged me, I was to deny I was Jewish. We could never forget to lie; our lives depended on it, and years later the memory of that would play a part in changing my life yet again.

Sometimes my mother was able to get hold of some liquor and sell it at a profit to make additional cash, and she also had some money left from our business in Katowice. She was brave, clever, entrepreneurial and good-looking. Sometimes I think there’s a cost for women who are so good-looking; they were frequently harassed by men, especially in those difficult times. But my mother knew how to navigate the system and was very good at knowing who to talk to in order to get things, like forged documents. She also made connections with mountain guides at the Polish border with Slovakia and made arrangements with them to smuggle people out of Poland, helping quite a few people escape the country, including my aunt, uncle, me and a number of strangers.

By the early fall of 1943, staying in Poland became too dangerous for me; we were sure authorities would discover that I was Jewish. So like the mother of Moses, my mother had to let me go to save me. My mother was a very courageous woman, and I will always admire the unimaginable emotional strength it must have taken for her to send her young son into unknown dangers to give him a chance at life.

My mother’s plan was for me to be smuggled out of the country through passes in the Carpathian Mountains to Slovakia, and eventually on to Hungary. So in September 1943, when I was still eleven years old, she paid one of the mountain guides she knew to take me out of Poland along with three other men, one of them being Marcel Waller, the family friend I’d lived with briefly in Bochnia. I was still so young that all the men seemed very tall to me, and I also remember one of them being young and very muscular, although I don’t recall his name. The third man, whom I called “Mr. A,” was a bit older than the others and his wife and child had been killed by the Nazis. I don’t know how my mother knew him, but he had relatives in Budapest, our final destination, because at that time the Jewish communities in Hungary were safer than those in Poland. In exchange for my mother arranging and paying for his escape to Budapest, he promised to take care of me when we arrived there.

***

Mr. A, whom I’d never doubted would take care of me, had just abandoned me. It was undoubtedly the most traumatic moment in my life. I was an eleven-year-old boy, I did not speak Hungarian, I was all alone in a large foreign city, I had no documents and my possessions amounted to what I was wearing. I had no money, no friends, no family, and I knew that if I were to be arrested, I could be deported back to Poland — a certain death sentence.

The other refugees there realized that a Jewish child had just been deserted, and they tried to do something about it. It was reassuring that they spoke Polish and were trying to help me, but on the other hand I didn’t want to be in a situation where I felt so helpless. They started to collect money, which they tried to give me, but it made me feel very inadequate, and my parents had always told me not to take money from anybody. This was very deeply ingrained in me, so I refused to take the money, even though I could have used it. Even now, when I think about that day, I feel like crying, and years later, when I started to talk to others about my experiences and got to that part, I did cry. Now, having told my story numerous times, it doesn’t affect me as much; after a while you become immune.

An Emotional Reunion

We were in Bucharest, Romania, when the war finally ended in May 1945, and I remember the celebrations; the streets were filled with people singing as loudly as they could. We stayed in the city for a couple of months before leaving for Oradea a town on the Romanian-Hungarian border in a territory that had moved back and forth between Romania and Hungary a number of times.

Toward the end of 1945, after about three years apart, my mother found me. She and my sister had also been liberated in Hungary, but it was a few months after I was liberated with my aunt and uncle. The Polish committee in Hungary had resettled Polish Jews in different parts of the country, and my mother was placed as a cook in a large Polish workers’ community in Budapest. By that time, my uncle was working in Oradea for the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (the Joint), which helped Jewish refugees, and my mother found us there and took me back to Budapest with her. I shall never forget seeing my mother after such a long separation; it was a very emotional reunion. I was not sure if she and my sister had survived the war, so it was a very heartwarming moment.

I was an eleven-year-old boy, I did not speak Hungarian, I was all alone in a large foreign city, I had no documents and my possessions amounted to what I was wearing. I had no money, no friends, no family, and I knew that if I were to be arrested, I could be deported back to Poland — a certain death sentence.

Speaking Out

I had never hidden it, but even today when I’m interacting with the rest of the world, with people I don’t know, I still feel uncomfortable; my Jewishness is not something I advertise because I’m aware that antisemitism is still very much part of society.

In 1990, during my year as a visiting scholar at MIT and Harvard, my wife somehow got involved with a group of child Holocaust survivors who met regularly in the Boston–Cambridge area. I went to one of their meetings, and for the first time I started to talk about my own experiences. When I did this, it was so painful I started to cry. Some of the survivors, Hungarian Jews, were in tears when I mentioned what had happened to me in Budapest when I was abandoned. It was the first time I’d been able to open up about any of this, likely encouraged by the candour of others. I’ll never forget one of the women there; I think she was a professor at Harvard who had survived Auschwitz with her mother. She told us that at one point she was freezing — they were made to stand outside with hardly any clothes on — and she said to her mother, “I’m so cold, I’m freezing,” and her mother said, “Look at the beautiful sky; the sun is shining.” In other words, sometimes, even in extremely difficult situations, you can attempt to change your own perception of a very challenging reality.

When Halina and I returned to Cincinnati from Boston, I reverted to my previous silence regarding my Holocaust experiences, but things began to change. One night after I got home from the university, I turned on the television and happened upon Return to Poland, a 1981 documentary on the Public Broadcasting Station (PBS). It was about how one boy had survived the war and revealed that at one very low point his mother had wanted to commit suicide and take him with her; they were standing on top of a building in Warsaw and she was about to jump but in the end did not. In the film the film’s director, Marian Marzynski, mentioned that his family, the Hermans, were from Łęczyca, Poland. When I was very young, my father took me to Łęczyca to meet my great-grandmother and our other relatives, so I knew there had to be a connection. I went on to learn that Marian Marzynski was not only a well-known documentary film producer but also my distant cousin who would go on to play a pivotal role in our lives. I had to find out about Marian, so I called the local TV station, and they told me which station to call for more details. I obtained Marian’s phone number and phoned him. Initially he was very suspicious, but by the time we finished talking he was convinced and decided that he and his family, including his elderly mother, would come to our son’s bar mitzvah. Once there, Marian’s mother and my father reminisced about Łęczyca.

***

There are not too many of us left. We are the last living witnesses to the sufferings that took place in the Warsaw ghetto and other parts of Poland and Europe. We, the child survivors, have to be the spokespersons for those who were so brutally murdered. We have to raise our voices on behalf of those who are no longer with us; we have to confront the Holocaust deniers. After us, the responsibility of educating the world about the Holocaust will have to be carried by future generations of our children, grandchildren and their children.