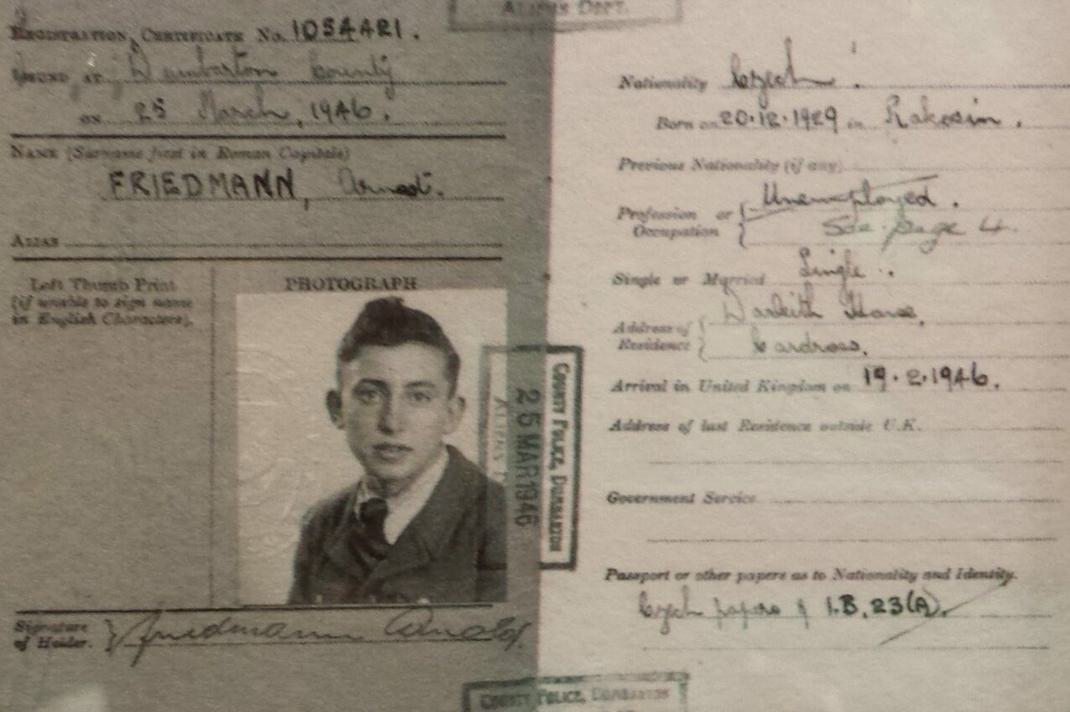

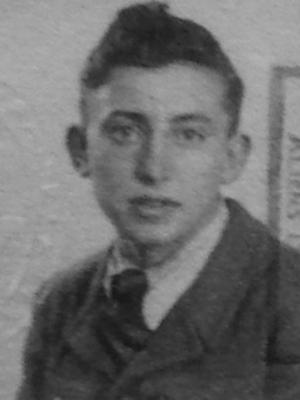

Arnold Friedman

Born: Chudlovo, Czechoslovakia (now Khudlevo, Ukraine), 1928

Wartime experience: Ghetto and camps

Writing partner: Phyllis Shragge

Arnold Friedman was born in Chudlovo, Czechoslovakia (now Khudlevo, Ukraine), in 1928. Before the war, his family moved to the village of Rakoshin (now Rakoshyno, Ukraine), which came under Hungarian rule in 1939.

In 1944, soon after the German occupation of Hungary, Arnold separated from his family; at different times, they both ended up in the Munkács ghetto. In the spring of 1944, Arnold was sent on a transport to Auschwitz-Birkenau soon after his family had been deported there. In January 1945, he was taken to the Gross-Rosen concentration camp and then to the Dachau concentration camp, where he was liberated by American soldiers in May 1945. Arnold’s family did not survive the war. Arnold went back to his village in Czechoslovakia after the war, but soon left for Scotland with the help of a Jewish community organization. He then came to Toronto through the Canadian Jewish Congress and the War Orphans Project. In 1959, Arnold married Lili, with whom he raised a family. Arnold worked in a variety of professions and sought to educate others about his experiences during the Holocaust. Arnold Friedman passed away in 2015.

The Villages of My Childhood

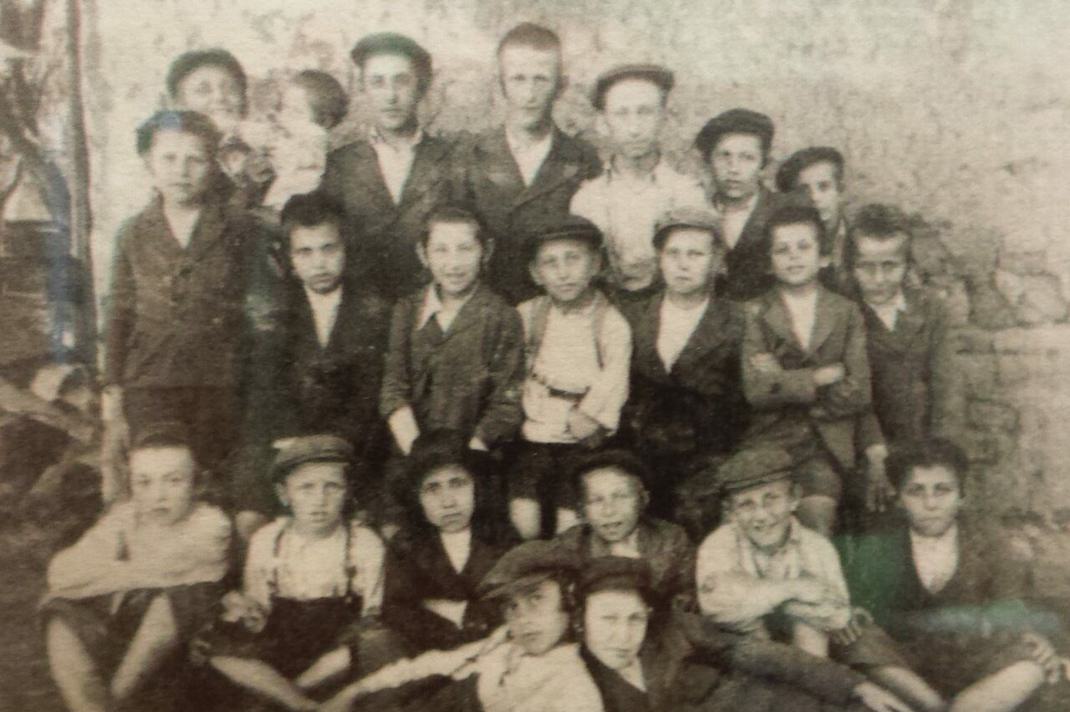

I was born on December 20, 1928, in the small village of Chudlovo, Czechoslovakia (now Khudlevo, Ukraine). My family consisted of my parents, Esther and Zelig Friedman, me and my four younger siblings. I had two brothers and two sisters, all born two or three years apart: Shlomo Zalman, Herman, Bella and Shaindie.

My birth village of Chudlovo was small and it had no great assets, no great story. It was a poor farm village consisting of about 210 houses surrounded by forests. The population was mostly Ruthenian and they spoke a local Russian dialect. There were twenty Jewish families. The Jews were traditional, without extremes in their observance of customs and rituals. There was one synagogue and there was one shochet (slaughterer for kosher meat). Everyone was part of the community.

The mornings began with the sound of the shepherd’s trumpet as he gathered the sheep in the middle of the village to take them out to pasture. It was a simple life.

In 1929, most of Chudlovo was destroyed by a fire. A Jewish-American family from Pittsburgh had come to visit their elderly relatives in the village and wanted their American-born children to meet other village children. One day, the village children entertained the American children by building a fire in the backyard so they could bake potatoes. Unfortunately, they could not control the fire, and the flames reached the thatched roof of the barn. The roof started burning. One of the neighbours later confessed that when he saw the fire he said to himself, “It’s a Jewish barn — let it burn.”

Of the 210 houses in the village, 198 burned down. The family from Pittsburgh had to run off very quickly to avoid being lynched. That was the atmosphere back then.

At the time of the fire, one of my uncles owned a bus that travelled between two major cities in the area. He heard about the fire and drove to Chudlovo to rescue my family. We were taken to my paternal grandparents’ village of Rakoshin, and that’s where I grew up. The village of Rakoshin (now Rakoshyno, Ukraine) is near Munkács (Mukachevo after the war). Rakoshin had been part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire when my father was young and became part of Czechoslovakia after World War I. In 1939, for a few short months, it became part of an independent Ukrainian country but was soon returned to Hungarian rule. After World War II, it became part of the Ukraine.

Rakoshin was a bigger, more cosmopolitan village of about 5,000 people. There were fifty-two Jewish families. The village was divided by a river, which was the lifeblood for both the people and the animals. On one side of the river were Hungarians; on the other side were Ukrainians. The Jews were spread out on both sides. The Hungarian villagers only spoke Hungarian, and the Ukrainians only spoke Ukrainian. Obviously, they did not speak to each other. They were neighbours, but they had different languages and different cultures. Although they were all farmers, the Hungarians used horses for daily activities, while the Ukrainians worked with oxen. The Jews spoke both languages and also spoke Yiddish among themselves. The Jews of the Ukrainian side of the village spoke Yiddish with a Ukrainian accent; the Jews of the Hungarian side spoke Yiddish with a Hungarian accent.

We lived in a two-room house. Half the house consisted of a general store where you could buy anything from chocolates to household goods, even naphtha for lamps, since electricity had not yet reached most of Rakoshin. The other room, where we lived, was divided by a wooden partition with tongue-in-groove boards. The living room section was identified by a table; the kitchen contained the wood stove. In the living room area, the table alternated between two functions, a table and a bed, as it had a plank that could be removed and replaced with bed covers. That was where we children slept.

From the open front door, we could see some chickens and ducks. We had one cow in the barn. We grew vegetables, such as corn, beans, peas, potatoes and carrots. Our life was farming and the store, which my father looked after, except when he was in the military camp. My mother took over the responsibilities of selling the wares when he was gone. In the winter, women in the village would congregate in each other’s homes. Sometimes they would pluck feathers to make a duvet bed cover for a girl’s dowry, or maybe they would engage in a sewing project.

When I was about ten, we had one cow and needed another one to help pull the wagon to bring hay home for the winter. My father borrowed a neighbour’s cow and yoked the two cows together to pull the wagon of hay. When the wagon was bogged down and wouldn’t move, my father had no choice but to hit our cow. I asked him, “Why don’t you hit both cows?” My father replied, “It is necessary to hit our cow, but I do not want to hurt the neighbour’s cow.” That story is etched in my memory to this day. It is a simple tale, yet it reflects a concern and care for borrowed property.

***

In Rakoshin, there was latent antisemitism, but it was tempered. As Jews, we knew that during Easter it was best to keep to ourselves. I remember Easter being the time when the non-Jewish Hungarian and Ukrainian children gave us dirty looks and occasionally threw rocks at us for crucifying Jesus.

During the rest of the year, the atmosphere was respectful. Everyone knew that our store was closed on Saturday, our Sabbath. Everyone respected each other’s religion. On Yom Kippur, for example, Jewish people would go outside the shul (synagogue) wearing tallisim (prayer shawls). The villagers realized it was a Jewish holiday and left us alone. When the Roman Catholic Church had a parade, the Jews would congregate on the streets with the other villagers to watch the procession. People in every culture depended on one another and respected one another.

Auschwitz: 1944

I recall being loaded onto a train, a cattle train with open slots for air to come through the walls. About 90 to 120 people were crowded into a small wagon, so there was little room to move. The train was rickety and the floor was covered with some straw. There wasn’t much room to sit or stand. You would have to take turns sitting or standing while the person next to you did the opposite. I was young and alone — I didn’t know a single person on the train and I had to depend on myself. I remembered the advice of my father who said, “Don’t listen to anybody, but hear everybody.” He also had instructed me to: “Be like a cat. Wherever fate throws you, land on your feet.”

In the train, children were crying. The barrel of drinking water for the journey was dirty and warm. The heat in the train was oppressive. We were given an old wooden tub to use as a latrine. There was no privacy, but often a blanket was held up as a shield. As we travelled, the latrine was sloshing all over. The smell was terrible.

I don’t remember the faces of the people on the train, but I remember the pained expressions of the sick and the elderly men and women. I remember the hungry, crying babies and their mothers. I remember the men peering through the cracks in the wagon wall in an attempt to guess the train’s destination. Was it destined for farm resettlement in some Hungarian colony to help in the war effort?

They will be forever in my mind.

Within a short time of our arrival at Auschwitz, we had transformed from our former selves into unrecognizable creatures. I’ll never forget one man from my village. He had owned a brewery with a number of employees and had had a large farm. I could picture him in his horse-drawn carriage. He was considered aristocracy in the village. Now his hair was gone, and he was wearing a ratty, striped uniform, but worst of all was the dazed look in his eyes. He was shorn of his dignity.

Another man, a scholar, had managed to take some paper with him on the train to Auschwitz. He had been writing a book, and his paper meant everything to him. He was dumbfounded. “They took my paper away,” he cried.

I joined a group of teenage boys, ranging in age from about thirteen to sixteen. We were all boys from Hungarian-occupied territories and we all spoke Yiddish, so we had no difficulty communicating with one another.

We were ordered to march to a camp, where we occupied about four barracks. As we passed the wire fence surrounding the perimeter of the camp, we were warned that it was electrified and we would be electrocuted if we tried to escape.

It was now June 1944. For the most part, we were in good health when we arrived at Auschwitz. We were young, strong and able to cope. It didn’t take us long to become accustomed to the routine of the camp. At approximately six or seven o’clock in the evening, we were locked up for the night. We slept in three-tiered beds, ten of us to a bunk. We rolled up our pants to use as pillows and shared one thin blanket.

We had similar backgrounds. We observed Jewish traditions and understood the importance of our faith. Each night, before going to sleep, we prayed.

In the morning, a loud gong would strike when we had to get up. We went to the toilet barracks where there was a row of toilet holes. Then we would run to the next barracks to wash. Water came through pipes, and we were able to splash some on ourselves. Then we returned to our barracks, where we had to stand at attention and be counted. After the count was confirmed, a meagre breakfast was distributed.

Soon the adults marched off to work. Our group was not required to work. Until early August, we spent our days observing the goings-on at the camp.

We knew that the sick and the weak (referred to as Muselmänner) were murdered. Some Jews who became too weak to work were sent to the gas chamber within a few hours of arriving at the infirmary. If a prisoner was sent to the sick barracks for anything more complicated than a minor injury, it would not be long before he was selected for elimination by a Nazi officer who made regular visits there. If there was an infectious disease, the whole group would be sent to the gas chamber.

We observed the atrocities at Auschwitz, but we were young, high-spirited and indifferent. We watched a crematorium, which looked like an industrial building with a big, fat chimney. At first, we thought the chimney was coming from a kitchen, but eventually we learned the truth. We saw the smoke. We smelled the smoke. At night, we saw the flames.

***

We knew our families were gone. The only visible families were the Roma families (called Gypsies at the time) and Czech Jews from the Theresienstadt ghetto and concentration camp who had been kept in family units in Birkenau. On July 10 and 11, 1944, the Czech family camp was emptied, the prisoners all murdered, and then on August 2 the prisoners in the Gypsy camp were all loaded onto trucks and hauled away to the crematoria area where they were all killed in the gas chambers.

Even as Germany was losing the war, the Nazis didn’t give up their quest to murder the Jews. Although the Nazis didn’t have enough trains to bring their soldiers to and from the front lines, they still had enough trains to transport the Jews.

On the Jewish holiday of Sukkot, five days after Yom Kippur, I noted that the Nazis made their selections on Jewish holidays, as if they were defying the Jewish God with sacrifices of His people. Sukkot is an eight-day holiday, and on the last day, with the Soviet front coming closer, there was yet another selection.

That day, we were marched to a clearing at the back of the camp. There were goalposts where the kapos would string up a volleyball net after they locked us up for the night. One of the SS officers found a piece of strapping on the ground. He nailed it to a marker on the goalpost, and we were ordered to go single file under the marker. I had been through several selections by now. My mind told me to beware, to not go under that marker. I soon realized that all the tall, healthy kids were sent to one side, and all the tall, skinny kids and the short kids, like me, were sent to the other side. I knew where I wanted to be. I wanted to be with the tall and healthy. I kept moving backwards to the rear of the line. I didn’t want to go under the marker. One of the SS officers yelled at me, “Get back in line!” I said that I wanted to be with my younger brother, and I kept backing up in line. The line was moving fast. All at once, I noticed that the officer who was supposed to watch the tall kids had turned around. I pushed my way into the centre of the group and grabbed a couple of bricks and stood on them. Being in the middle of the boys, I looked as tall as the rest of them. Suddenly, I felt the kapo grab at my neck. I ducked and started to run away. At that instant, the officer shouted at the kapo to “get over here and stand guard” because the selection process had finished. So I got away with it. I think I may have been the only one in the group of short kids to survive.

People ask, where was God during all of this? I say, where was humanity?

The Scars Remain Forever

After the war, I made my way back to my village. I was not welcomed by the villagers, who seemed surprised that I had escaped death. My homecoming was not a positive experience, but it did not come close to what I heard the Polish Jews endured. When many Polish Jews returned to Poland, they were killed by gentiles who worried that they would want to reclaim their property.

I was sixteen years old. I couldn’t try to claim my farm, as I wouldn’t have known how to run it. Even if I did, I didn’t have the animals and necessary supplies.

I went back to Czechoslovakia and stayed with some older cousins for a few weeks. I registered with a Jewish community organization and found out that war orphans sixteen years of age and under could go to Britain. I wound up in Scotland in a castle on a farm. My group was there for almost a year so we could be rehabilitated, “re-civilized.”

Eventually, we were moved to Glasgow, where we were encouraged to look for jobs. We were told that before we turned eighteen, we had to decide where to live. We had to either apply for British citizenship or apply for an international passport to any country that would accept us.

Many of us prepared to go to Israel, called British Mandate Palestine at the time, but the British would not allow that, and I wanted to get as far away from Europe as possible.

I heard that the Jewish community in Canada allowed youth into the country under the auspices of the Canadian Jewish Congress and the War Orphans Project. They were willing to take some Jewish orphans.

When I arrived in Canada, I stayed in a hastily converted Jewish library on Markham Street in Toronto for a few months. People wanted to help us. Some families took children in on a temporary basis, and others wanted to adopt an orphan. I was about eighteen at the time and old enough to live on my own. I just wanted room and board. However, I wound up with a family in Guelph for several months. It seemed that the parents wanted an older brother for their son and daughter. While in Guelph, I was sent to school and I was in a classroom with children much younger than me, about thirteen or fourteen. I wasn’t very comfortable at school or in the family’s home. The situation didn’t work well for me or for the family. I was sent back to Toronto under the supervision of the Jewish community.

I looked for job ads in the Toronto Star and the Toronto Telegram. There was an ad for a job at Globe Envelopes on Ontario Street. I had an interview and was told I got the job. Then I was required to fill out an application, and when I signed my name, the man said, “Oh, you’re Jewish. We don’t hire Jews.”

By then, I was a bit hardened to the climate of the times, so I had the nerve to ask why they didn’t hire Jews. The fellow said that it was company policy, but he agreed to talk to the manager. He left the room, and when he returned, he related that the manager had said, “If the Jew-boy wants the job so badly, give it to him.”

***

Now, decades later, I speak to groups of school children throughout Toronto. I tell my story at the Holocaust Centre (now the Toronto Holocaust Museum), schools, libraries, bookstores and synagogues. I have been interviewed on the radio and by print journalists. I was one of the chief witnesses at the trial of Holocaust denier Ernst Zundel. I feel it is my responsibility to tell people about my experiences during the Holocaust, so future generations understand what happened. I want to pass on the lessons of humanity’s horrors of the past.

People ask, where was God during all of this? I say, where was humanity? One of the reasons I talk to students is to point out that intelligent people can become murderers — brutal murderers and executioners. There was a cold-blooded plan to commit mass murder against the Jews. How did the Holocaust happen? Future generations will try and be dismissive and put all the blame on Hitler. It wasn’t just Hitler. Educated people were determined to remove the Jews and confiscate their property, even if it meant murdering them all. The economy was the key factor. In civilization, respect for human life is the most sacred value. If we haven’t learned to respect life after the Holocaust, what have we learned?

I am uneducated, yet I succeeded in business. I am not an academic, yet I am interested in philosophy, religion and history. I write poetry — some serious, some humorous. I teach, but I am not a teacher.

As I reflect on life, I realize that it is bittersweet. You have to have a sense of humour if you want to survive the bitter reality of life.

My wounds have healed, but the scars remain forever.