Liberating Our Stories

Rachel Shtibel

Born

1935, Eastern Galicia

Survived the War

In the Kołomyja ghetto and in hiding

Liberation Date

April 1944, Kołomyja, Poland (now Ukraine)

Liberators

Soviet Red Army

By April 1944, Rachel Shtibel had spent over a year hiding under the floor of a barn. She shared a shallow pit with nine other people, including her parents. After they found out that their town of Kołomyja, Poland, had been liberated, the Shtibel family was told to leave the farm, and they made their way to the nearby forest. Rachel had not walked upright or spoken above a whisper for months. How would she get the attention of the Soviet soldiers?

Rachel playing the violin, 1949.

It was already dawn when we reached the main road. Tanks were moving heavily, one after another, but we just lay in the ditch by the side of the road hoping that someone would notice us. My father was teaching me the word for “Jewess” in Russian. He kept making me repeat, “Ya Yevreyka.” (I am a Jewess.) It was no use though. I could not make my voice speak. No sound came out and I could only move my lips to the words.

We did not have to tell them who we were. They understood.

Background image: Rachel’s aunt, Mina Blaufeld (right); Rachel at five years old (back, middle); and Aunt Mina’s cousins. Undated. (Photo found in Uncle Velvel’s violin case.)

After what seemed like a very long time, one of the soldiers saw us and ordered the tank to stop. Two soldiers got off the tank and picked us up.

I was afraid to tell them I was Jewish. When we escaped from the ghetto, we had ripped off the bands with the Star of David that identified us as Jews. Now I was to tell these soldiers I was Jewish? When the Soviet soldiers picked us up they noticed that there was a whole group of people in the ditch. We did not have to tell them who we were. They understood.

After the war, Rachel and her family dug up a violin case that had belonged to her beloved uncle Velvel. He did not survive the war but had buried the violin before the family was forced into the Kołomyja ghetto. Many years later, Rachel realized that the contents of that violin case were more significant than she thought. Rachel was not who she thought she was, and she began to uncover a long-buried truth.

Rachel's biological mother, Nelly (left), and Uncle Velvel’s cousin Minka (right). Undated. Rachel’s only photo of Nelly. (Photo found in Uncle Velvel’s violin case.)

I looked like him. My parents kept his memory alive so fervently in me while I was growing up. His violin was given to me and only I was to play it. In the violin case he had placed my baby pictures, pictures of himself and a picture of his cousin Minka with a girlfriend. But who was this girlfriend? An enlargement of Velvel’s picture hung over the grand piano in our living room in Wrocław and a picture of me was hung beside it. My parents had spoken often of Velvel and his love affair with Nelly. I went over and over these clues in my head. Velvel must have been my biological father. Nelly must have been my biological mother.

Rachel's uncle Velvel, wearing the embroidered shirt he often wore for his violin concerts. Undated. (Photo found in Uncle Velvel’s violin case.)

After such a traumatic discovery, I needed an outlet.

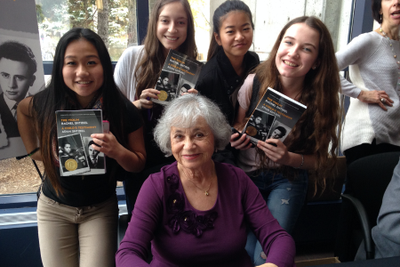

Rachel sharing her story with students. Markham, 2014.

At age fifty-eight, after such a traumatic discovery, I needed an outlet for all I felt. I had a deep urgency to share my discovery with others. At first, I talked to my grandchildren about my history. I was determined to teach them about the Holocaust and about my own childhood. They were very interested in my stories and asked me to write a book about my life. The idea of opening up the memories of the past again frightened me. Did I have the strength to relive the nightmares of my childhood, the horrible experiences of the Holocaust?

I wanted our children and grandchildren to remember and the world to know.