Peter Theimer

Born: Prague, Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic), 1926

Wartime experience: Escape

Writing Partner: Chris Dingman

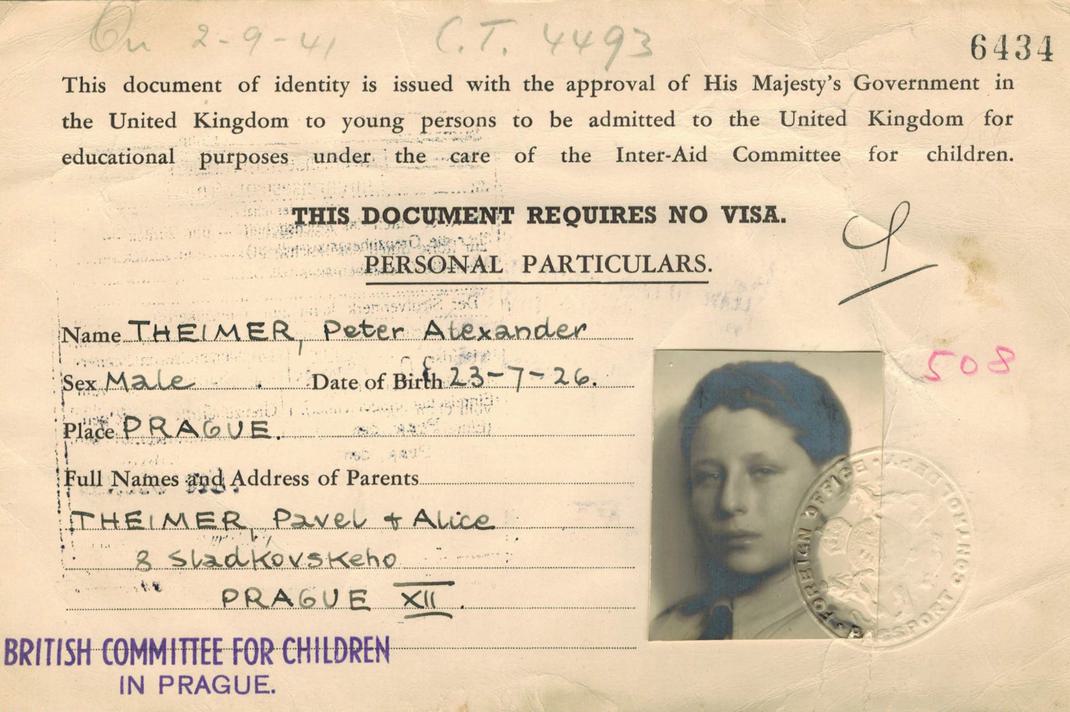

Peter Theimer was born in Prague, Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic), in 1926. After Germany annexed Czechoslovakia in 1939, Peter’s parents sent him to England on a Kindertransport.

Peter attended school in England, and in 1944 he volunteered for the Czech Free Army in England and joined the Allies in Europe after D-Day. After the war, Peter returned to England, where his mother eventually joined him. In 1951, he immigrated to Canada, settling in Toronto, where he married and raised a family. Peter had a successful career as a systems specialist, working for almost two decades at Mt. Sinai Hospital, and spoke to local groups about his wartime experiences. Peter Theimer passed away in 2019.

Escaping on a Kindertransport

I developed my love of music when I was young. My parents took me to the opera and the symphony. I heard Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony for the first time with my father, and Mozart and Verdi were my favourite composers. We had a grand piano in the salon at home on which my mother would practise daily; she would play and sing — she had a beautiful voice — and I would often join her to sing duets. Mother also took weekly singing lessons. Her sister, Charlotte, my Aunt Lotte, also sang and Mother would say she had the better voice, but she was flighty and didn’t pursue music as stringently as my very thorough mother did. Father seemed to enjoy listening to us but was more interested in chamber music and the symphony.

Mother and a few of her friends would meet in the mornings for coffee at Lippert, a very fine delicatessen, where they served the most fabulous lobster or crab open-faced sandwiches. There was also a coffee house in Prague called Berger, where they would meet at 5:00 p.m. for an afternoon coffee. Occasionally I would join them; at Lippert’s I would get a lobster sandwich, and at Berger’s I would get chocolate ice cream and the occasional cake. One of the jokes I would tell in later years is that I was born on a Friday afternoon when Mother was at Berger’s.

Mother loved the arts and had quite the social life. For a month each summer, she would rent a villa near a body of water. Mother and I would go there with my governess. My father would join us for a week or so, and sometimes my grandmothers Theimer and Soyka would also join us. I still have a photograph of my father in his swimming shorts at a villa we rented in Germany on the Baltic Sea. As I got older, eight to ten years old, Mother and I took trips, just the two of us. We went to Belgium and the Netherlands, and in the summer of 1938, we took a holiday in England. Mother parked me in a summer boarding school on the coast in Little Hampton, Sussex, for part of the holiday while she toured England’s stately homes, art galleries and museums.

While I was safely parked at the school, the headmaster introduced me to the local Scout troop and its Scoutmaster, the Reverend Thomas Percival Payne. A single gentleman, probably in his thirties at the time, he also ran the congregational church.

He welcomed me to troop meetings and made me an honorary member of the troop. I went to several Scout meetings and was invited to go for a week to their two-week summer camp at Gog and Magog Lodges near Petworth, Sussex.

The summer of 1938 was a very agitated time. My father was almost constantly on the phone that year with his friends throughout Europe; when the Germans annexed Austria earlier that year in March, he heard from friends in Vienna all about the miserable things that were being done and he became worried about what to do. The Munich Agreement was signed in September 1938 and with it, the Sudetenland, Czechoslovakia’s northern and western border regions, was annexed by Germany. We were quite well informed about the Nazi agitation in the Sudetenland; everybody knew what was going on. There were demonstrations and everyone believed the Czech President Edvard Beneš could solve the problems, but he went into exile in France and things continued to get worse.

Czechoslovakia was betrayed by its allies and was therefore defenceless against the very large and militaristic German state. No one had an appetite for war — not our allies or even Czechoslovakia’s own people. The French were hesitant about getting involved and so Britain didn’t step in either. Then, on March 15, 1939, the Germans took over the remainder of Czechoslovakia and it became the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.

One day as I was walking to school on a street that ran parallel to Wenceslas Square, one of the main city squares in Prague, I could see SS thugs dressed in their black and silver uniforms, playing martial music and goose-stepping up and down the square. It scared the daylights out of me.

After the German occupation, a letter arrived from Reverend Payne urging my parents to send me to England where he would look out for me; of course, my parents would have to pay school and other expenses because congregational ministers didn’t usually have much money. Even though I didn’t understand, I remember the troubled atmosphere at home at that time and the discussions between my parents. I don’t remember the details of what my father told me, but eventually my parents accepted Reverend Payne’s invitation and he became my sponsor for the Kindertransport organized by Sir Nicholas Winton. My parents’ decision to send me to England, in combination with their influence, came to define my character for life.

My parents enrolled me in one of the transports, and on June 29, 1939, my family bade me farewell as I boarded the Kindertransport at Prague’s Wilson Station, now known as Hlavní nádraží or Central Station. It was the last time I saw my father. I left my family on one of the last transports to leave the country and to safely deliver children to England. The final transport organized by the Winton organization was for September 1, 1939, but the Germans stopped that transport, and I think only two of the approximately two hundred and fifty children it would have carried to safety survived.

Peter, age one. Prague, Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic), circa 1927.

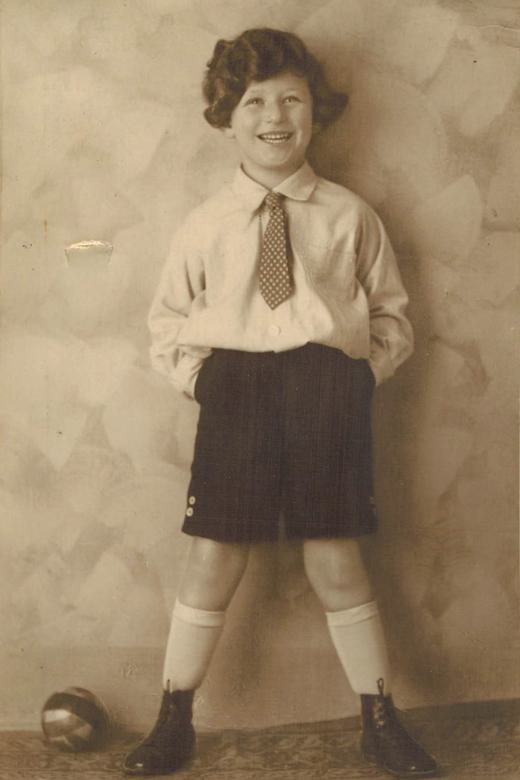

Peter on his first day of school. Prague, circa 1932.

I left my family on one of the last transports to leave the country and to safely deliver children to England…. My parents’ decision to send me to England, in combination with their influence, came to define my character for life.

Between Christianity and Judaism

I arrived safely at the Liverpool Street Station in London on July 1, 1939. We were met by the assorted parents, guardians and sponsors of the various kids. I was met by Reverend Payne, but I waited for a long time because his train from Littlehampton to London had been delayed. I wasn’t worried because the Kindertransport people were there, taking care of the children and releasing them to their sponsors.

A few days later, I was shipped out to the Shoreham Grammar School, now known as Shoreham College. The school, on the south coast of England, about fifteen miles from Littlehampton, was the boarding school I was registered to attend in the fall term, but I had now arrived early!

I used to attend Reverend Payne’s church on Sundays; he was a good preacher and a very fine man, so I felt no compunction about attending his services. He knew I was Jewish and left it up to me entirely whether I attended the services or not. A few minutes after the service began on Sunday, September 3, 1939, the sirens started, signalling that war had been declared. Reverend Payne said, “We all know what this means. I guess we are at war with Germany so for today we will close the service early to let you go back to your families with a short prayer to accompany you.” So we dispersed. On Monday, Reverend Payne volunteered for the army. Shortly thereafter he was shipped out as a chaplain to the forces with the rank of captain.

Family friends from Prague looked after me after the reverend left. In late 1941 or early 1942, these friends invited me to their home in Hertfordshire for a weekend. Once there, they told me that Father had died. The Petschek family had made their fortune in coal mining and established the bank, where my father worked as a vice president, to handle the financial end of their business. They had been on the Germans’ wanted list and had seen into the future with the German annexation, so they sold their assets and moved to England. They took a private train across Germany. Many of the bank’s directors also left Czechoslovakia. My father, a man of great honour, could not leave because he knew how important it was that people continued to have confidence in the bank. But after the Germans occupied Czechoslovakia, they confiscated the Petschek Bank and moved the remaining bank personnel out of the beautiful building where the bank was housed, known as Petschek Palace, which the bank had sold just before the occupation, and into an apartment house. The Petschek Palace was then converted to the Gestapo’s headquarters in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and became the infamous Pečkárna, a notorious place where the Gestapo specialized in interrogation, torture and murder. The Germans appointed the group of remaining senior vice presidents and directors, including my father, to liquidate the assets of the bank, which they completed within a few months or so. The Gestapo then collected my father and his colleagues at 2:00 a.m. one night and shipped them off to Mauthausen concentration camp. Once there, sometime in the late fall, my father was killed; we never found out the exact date, but we think it was November 1941. After my father’s death, representatives of the Petschek Bank came forward and offered to subsidize my education in honour of my father. They named Oswald Stein, a businessman, as their representative and my sort of guardian.

After Reverend Payne left to serve in the war, I was officially under the patronage of a series of Church of England ministers, who were usually also the heads of local Scout troops. Sadly, they did not respect my Jewish heritage the way Reverend Payne had. Even so, I continued to go to church and inevitably, before or after services, there would be discussions about the principles of the church. One particular clergyman, a jolly, rotund minister in northern England, asked me what religion I was. I told him I was Jewish, and straight away while rubbing his hands, he said, “Don’t worry, my boy. We’ll soon put you on the right path.” I can see him now! I met him only that once. I also got into religious discussions with another reverend, Reverend Loasby, who was very tolerant. He was the rector at St. Peter’s Church in Ealing, a suburb of London. After several meetings, each of which had become progressively more interesting, the reverend invited me to join him at his home for private discussions, followed by dinner with him and his wife. He told me that it if I decided to convert it would be his honour to do so.

During my wartime stay in England, I had no contact whatsoever with the Jewish community. Nonetheless, I did choose to maintain the Yom Kippur fast. Contact with individual Jews was limited to friends of my parents who had fled in time and had established themselves already. Most of them were fairly secular.

When I was about fifteen years old, I was able to make a conscious choice between Christianity and Judaism. Even with the small amount of Jewish education I had, I found I could not relate to Christianity; it seemed to me that Christianity depended on taking too many things on faith. I felt Judaism was more rational and because of that I could accept it with both my head and my feelings, so I stayed a Jew.

Going to War

Because an invasion of England by Germany was expected, at the end of the 1939–1940 school year, the boarder operations of Shoreham were evacuated from the English Channel coast to a country mansion some thirty miles inland. I continued my education there until 1942, when I matriculated at age sixteen. I was the top in my class in English and loved to write.

With the war continuing, instead of more school, I volunteered for the Czechoslovak Independent Armoured Brigade Group (CIABG); I was now Private Peter Theimer. I had enjoyed five years of Scouting in wartime Britain, becoming a troop leader and King’s Scout in the London troop, with which I became affiliated after graduating from high school and moving to London. When I joined the CIABG in June 1944, my active participation in Scouting ended, but the Scouting experience in orienteering, signalling and general camp craft proved useful in my training and my work as a signaller.

I spent about three months in basic training in Southend-on-Sea and then got shipped north to Bridlington, where the Czechoslovak Independent Army Brigade Group was briefly based. The related group, the Free Czech Army, was one of several “free” allied armies serving under the overall command of General Eisenhower but having their own officers, local staff and identity. I was assigned to a signal unit as a telegraph and switchboard operator attached to the artillery regiment. I spent two more months in training before we were shipped, in late July or early August, following the D-Day invasion, across the channel to France.

We spent a couple of weeks in the Falaise area of Normandy, France, a famous post-invasion battleground where the Germans were decimated; we’d drive along the road and see a hand sticking out of the mud — it was ugly. We trained there and then we were transferred to Dunkirk, a port in northern France that was one of the pockets where Germans were left behind by the main German armies. The Allies’ strategy at that time was to push as fast as they could to the Rhine and over the Rhine into Germany and not waste time on the little pockets of resistance; small groups of Germans in Dunkirk and other towns who refused to surrender could tie up quite a number of Allied forces. The Czech brigade took over the siege of Dunkirk from the Canadians in 1944. We garnered medals, battle honours and recognition for our service at Dunkirk.

Once while I was on duty as a phone exchange operator, the Germans started up something and there was an exchange of artillery between their side and our side. My captain said, “Okay, Theimer, you go up and keep watch on this sector and let us know if some Germans get through there.” I was so scared that I practically had to change my pants! I got up there and found a parked armoured car; I could see the sector I was supposed to watch by looking between the wheels of the car. So I crawled underneath it where I was at least protected by the steel of the armoured car. Then there was an exchange of weapons fire, and I could hear the pitter-patter of the shrapnel falling on the car. I saw some movement in the woods ahead of me and I was scared stiff. What was I going to do — shoot at the guy? I didn’t shoot and he disappeared; a few minutes later, the exchange was over. I was lucky that armoured car happened to be there to offer me protection.

I liked the army; during high school, I had been a keen participant in the cadet’s corps and at university I had been part of the officers’ training auxiliary, so when I joined the Free Czech I knew a hell of a lot more about army operations and weaponry than a lot of my mates. We stayed in Dunkirk until May 1945 when, on Victory in Europe Day (VE day), we got roaring drunk on Calvados, France’s famous apple brandy.

After VE day, we left France by convoy and crossed the Netherlands and Germany and eventually worked our way toward Prague. As a Brigade, we got permission from the Soviets to do a victory march through Prague at the beginning of June 1945. We felt apprehensive. We’d been away from home for four years and didn’t know what to expect. There were all kinds of rumours going around. A number of the Czechs had collaborated with the Germans; others had supported the resistance, and they had four years of experience of being under occupation. We came from a totally different background in England and we felt strongly English — especially the younger ones among us.

When we arrived, we all simply piled into trams or buses and headed into Prague. There was no one there to stop us! I didn’t take the streetcar all the way down into the heart of Prague. Instead, I got off it about three miles from the centre of Prague near the area of Prague Castle and walked. I just had to walk through those streets. I walked to the Vltava River where I crossed a bridge and continued to walk to the old town and on to Wenceslas Square, near where we used to live. It was a very strong emotional journey through the streets of Prague. It was such a beautiful walk and yet, for me, it was filled with ghosts.

***

My mother had also survived the war, but her journey had been far from easy. My uncle Bertie Richter was a great “fixer.” Married to Mother’s sister, Charlotte, Bertie was a banker in Budapest, Hungary. After my father’s death, he arranged for my mother to be smuggled out of Czechoslovakia. She fled through the back woods and across the Danube into Hungary. My mother stayed with her sister and brother-in-law for about a year and then stayed with various family friends for varying lengths of time. In 1944, Jewish organizations were trying to arrange a deal with the Germans — negotiating the release of Hungarian Jews who were going to be deported in exchange for valuable goods. One of the train transports, my uncle had been told, was intended to go from Budapest to Switzerland and then to Palestine. My uncle got my mother onto this transport. One dark evening, the doors of the train opened not in Switzerland but in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp complex — surprise, surprise. The Hungarian group was housed in a separate area within the camp. Eventually, toward the end of 1944, the inmates of that section were paraded, and the commandant told non-Hungarians to step out of the line; my mother and about six others stepped forward. The rest of the group were transported to Switzerland. It was during this move through Switzerland that a friend of my uncle’s who had been with Mother contacted my guardians in England and informed them that Mother was alive and in the Bergen-Belsen camp. It was such great news to know my mother was alive.

Eventually, the Soviets liberated Mother and the other prisoners. After staying with a farmer, my mother saw a Jeep arrive one day from the American Red Cross and she got a ride to Leipzig. She then went with one of the Czech consuls who was returning to Prague.

When Mother got to our friends in Prague, they told her that I had just left Prague and returned to my garrison near the border. She was shocked: “What was Peter doing in the army? He’s supposed to be in school in England!” My friend Anne knew how to find me, and no sooner had I arrived back with my unit than I received a call from her announcing that my mother had returned to Prague. I said goodbye and got a ride to Prague with the very next truck. I had been twelve years old when I left home for England, and here we were seeing each other six years later with me older and a soldier; it was such an experience. Seeing my mother alive after all those years was wonderful and we had an amazing and emotional reunion.

Peter with his mother in Wenceslas Square. Prague, 1945.

Peter in the victory parade. Prague, June 1945.

Peter’s reunion with his mother. Prague, 1945.

Canada

There was a scare in England in the summer of 1950. A couple of guys who worked in similar Czech export companies were arrested and accused of espionage for the Soviets. The Cold War was in full swing! I thought that, sooner or later, missiles would start flying east to west and west to east, and a few might land in London. I had had enough of military things, and at twenty-four years old I was feeling the need to establish a home and family. Various British colonies were offering incentives for people to move there. Since we had family and friends in New York, Toronto and Montreal, I decided to take advantage of the Canadian subsidy. In March 1951, I quit my job and flew to Canada. I had heard about the Canadian winter and had dressed as warmly as I could with tuques, gloves and sweaters. I remember landing in Iceland for a 2:00 a.m. stopover and seeing an absolutely gorgeous sky while freezing my butt off! It was very cold. In Montreal, I was met by family friends and the first thing I did when they took me to their home was to change into spring clothes because everything with four walls around it was about seventy degrees!

I started looking for a job almost immediately. I had some introductions, but even so I got a big shock. In at least six or seven places, the interviews went well — they would say it was too bad I didn’t have a university degree but would think of something for me to do and I would hear from them. Then the guy would take me to the door of his office, shake my hand and ask, “Not that it would make any difference but, by the way, what church do you go to?” or “What religion are you?” I was shocked, as I had never encountered this in England. I said, “I am Jewish,” and down would go the hand and he would say, “Oh, you’ll be hearing from us, Mr. Theimer.” I never did. After a few days of this, I decided to go to Toronto.

In Toronto, I encountered more of the same reaction from prospective employers as I had had in Montreal. Eventually I was pointed to the Polymer Corporation in Sarnia; it was a Crown company and forbidden by law to ask employees about their religion until after they were hired. I got a job as a foreman of the research laboratory’s production control department.

Like my father, I am not a small-town person, so I never expected to stay for long in Sarnia, but it gave me an opportunity to learn how things worked. In the spring of 1952, I started looking for a job in Toronto; by then fewer people were worried about religion. Eventually I found a job with A.V. Roe, a subsidiary of the well-reputed British Hawker Siddeley Aviation Group started during World War I. It manufactured airplanes, airplane engines, railway and other heavy equipment. A.V. Roe was located in Malton (now part of the City of Mississauga), just outside Toronto, and it was at this factory that the Avro Arrow airplane was developed.

***

During my first year and a half in Canada, my mother was living in London. She had lots of friends from pre-war times in London and led an active life there. There was an almost continuous bridge game — she was a fanatic bridge player — and she was very sporting: she played tennis, swam and skied. As much as she loved her life in London, it was important to Mother and me that we be together so, once I got a job and settled in Toronto, she moved to Canada in the late fall of 1952. The compensation Mother received from my father’s employers, combined with reparations from the Germans for war crimes, made it possible for her to make the move to Canada. There was a Prague clique in Toronto, so Mother had lots of friends before she even arrived. Mother was a very gregarious woman who met and befriended people easily. Initially, Mother stayed with the family of one of her childhood friends and schoolmates Frida Morawetz, until we found a house on Wells Hill Avenue, where we stayed until I was married.

***

I am so blessed to have Nancy as my wife and so proud of our children — Paul Leo, Lisa Ruth, Brian and Karen — and our three grandchildren, Gillian, Jeremy and Monique.

In recent years I have been giving talks on my wartime experiences at local temples and for seniors’ groups. It has given me wonderful opportunities to reflect on my life and today, at almost ninety years old, I find that I feel the same about religion as I did when I was a teenager. I was born a Jew by accident but have been proud to be a Jew by choice. I chose Judaism but it wasn’t until I was about sixty years old that I finally had my bar mitzvah.

Nancy and I have had a wonderful life and have many good friends. It is true that, at times, life has been difficult, but when I take stock I am always struck by my good fortune. I grew up in a loving family and enjoyed a very comfortable life filled with culture and travel. On vacation in England, I met a reverend who, when the Germans occupied our homeland, offered to sponsor my travel to England to escape Nazi persecution. My parents loved me so much that they found the courage to send me away into the reverend’s care, and in so doing most certainly saved my life. My father’s employers paid for my education, establishing the foundation for a fulfilling and rewarding career. I contributed to fighting the Germans without losing my life and was reunited with my wonderful mother at the end of the war. I immigrated to Canada where I met my loving wife, and together we raised four children who fill me with pride. And here I am at almost ninety years old, writing my memoir.

So, I see myself as very lucky indeed!

Peter at his ninetieth birthday celebration. Toronto, 2016.

Peter in Prague. Circa early 1990s.

Peter and Nancy under the tree where he had proposed to her. Toronto, year unknown.