Esther Tschaschnik

Born: Radom, Poland, 1923

Wartime experience: Ghettos and camps

Writing Partner: Phyllis Fien

Esther Tschaschnik (née Cwajgenberg) was born in Radom, Poland, in 1923. Before the war, she worked in a photography studio.

In 1941, the Jews of Radom were forced into ghettos, and Esther continued to work for the studio and then in the garden of a German-run hospital. Esther escaped the deportations from the ghetto to Treblinka in 1942 and was sent to the Pionki forced labour camp, where she worked in a munitions factory alongside her sister Sara and sustained an injury to her hand. In 1944, she was sent to Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen and forced labour camps. As the Soviet army approached, Esther and her sister and other camp inmates were evacuated and then taken on a death march. They were liberated by the Soviet army in April 1945. After the war, Esther returned to Radom with her sister and then moved to Munich, where she met and married her husband, Joseph, and her daughter was born. Esther and her family immigrated to Canada in 1948 and settled in Toronto, where she raised her daughter and son and worked in a photography studio. Esther Tschaschnik passed away in 2019.

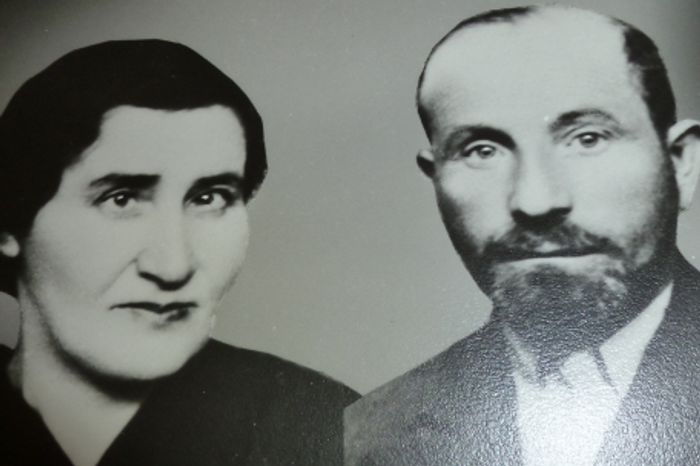

Esther’s parents, Israel and Rifka Cwajgenberg, before the war. Radom, Poland, circa 1930s.

Esther with her family before the war. In back, left to right: Esther’s mother, Rifka (left), and her father, Israel (right); the name of the person in the centre is not known. In front, left to right: Esther, her sister Sara, her brother, Rachmil, and her sister Kazia (Kendla). Radom, Poland, circa 1930.

The Radom Ghetto

After the Germans came into Radom in 1939, you could feel the change right away. Most people did not have work. I had work but my father was forced to leave his job at the leather factory. The Germans took the leather factory away from the Jewish owners as soon as they arrived, and I have no idea what happened to it after the war. My mother was still able to run her sewing-supply business because most of her customers were Polish.

We were forced to wear armbands so that when we went out, we could be identified as Jewish. In 1941, the Nazis put us in a ghetto that they made in the Jewish neighbourhood of the city. Every Jew in Radom was forced to leave their home and move there or into another ghetto. It was terrible. Everybody lived crammed together, many people in one room. Can you imagine, seven people in one room?

At the time we were in the ghetto, I had been working retouching photographs and finishing pictures for three years. Only those with a work card showing they had employment outside the ghetto, like I did, were able to leave the ghetto. Those who did not leave were harassed by the police. For the first three or four months, I was able to leave the ghetto because I had the right papers. But eventually I could no longer go out because I could not get the right papers, and I was forced to work in the ghetto. My co-worker would come from outside the ghetto, bringing me negatives to retouch and then taking them back to the studio. There were times, though, when I was able to sneak out of the ghetto and the Nazis did not find out.

I had a German-Jewish friend who told me that if I wanted to live, I had to work for Germans. Even if I could prove that I worked in a Polish photography studio, it wouldn’t be enough to save me. My friend arranged for me to start working in the garden of a German hospital. She worked in the hospital’s office and must have spoken to the German officer who was in charge there. Many people worked in the hospital, but only a few in the garden where I was and where the work was better. I had known this friend for a long time, from the time she first came to Radom from Germany. She did not survive the war. Even her sister who had married a German was killed. Few survived.

I remember an incident in the garden when one of the men who was working with me lay down and slept in a cabbage plot, and when he got up, we could see that he had damaged a few leaves. The German official in charge — it was his garden — happened to come over and see this. He asked. “Who did this?” I replied that I did not know. He said, “If I am not told who did this, I will shoot someone.” I stepped forward and said, “I did it.” He looked at me and said, “Go home.”

My sister Kazia was going out with a boy at this time, and they were engaged in 1942. Many of the girls in the ghetto got married and even had children. Kazia was engaged around Pesach and was supposed to get married shortly after, but that was not to be. On the eve of her wedding day, she was sent to Treblinka. She did not survive.

On the evening of the deportation, the Jews of the ghetto were called out to gather for a selection. We all had to stand in line for what seemed like forever. By the morning, my mother and little sister Malka, and my brother and Kazia, had been taken away. I have never forgotten what a Jewish policeman did for me that night. He opened a hole in the fence and took my friend and me to the other side, where those who had been selected to stay in Radom were standing. My friend and I were saved from being sent to Treblinka that night. Of the 30,000 Jews of Radom, only three thousand remained. Almost all of Radom’s deported Jews had been sent to Treblinka. The rest had to do forced labour in different factories. My father was not selected that time, but he was taken a year-and-a-half later.

I decided to try to leave with my sister to find food. I did not care if I died trying; I needed something to eat.

In the Camps

After most of the Jewish community of Radom had been sent from the ghetto to the death camp of Treblinka, I was sent with my sister Sara and others to the Pionki forced labour camp in the back of open trucks. The Pionki forced labour camp was an armament factory where munitions, gunpowder and explosives were manufactured.

While in Pionki, I cut my fingers badly and could not work. I did not know if my hand would ever heal. I was unable to move a finger of that hand. It was just bone. But somehow, with my sister Sara close to my side, hiding my hand, the Nazis did not see it.

In Pionki, we lived in barracks and were surrounded by electrified fences. It was at this camp that the Nazis almost shot me. This is what happened: There were Ukrainians and Poles in the areas where we went out to work. I got food from a Polish girl and was bringing it back to the factory so that I could sell it. But the guards caught me. A Jewish girl working in the camp office spoke to the German guards and tried to help me. I was sure they would shoot me, but I was detained for a few hours, and then they let me go. My sister was standing outside, waiting for me. I am very lucky because they usually took people away and shot them when they committed this offence.

When they closed Pionki because the Soviets were approaching, some of us were put on a train to Auschwitz but, at the time, I had no idea where I was going. We were transported in very crowded freight cars, standing for the entire journey. My hand was not healed, and it was bleeding. When we arrived at Auschwitz, they took everything away from us and gave us only a thin dress and shoes. We had nothing else, not even a sweater or underwear. I was in Auschwitz for a month.

Then we were taken from Auschwitz to a factory, where we stayed for three or four weeks. Then a group of us was sent to Bergen-Belsen. We were selected because we could not do the work in the factory. I was not able to work at all because of my hand. Many others could not do the work because they had never worked at a factory like this before. And when the Germans found out that we girls could not do the work, they sent us to Bergen-Belsen. I was in Bergen-Belsen for a month, and we had to sleep on the ground. From there, we were sent to a forced labour camp in Germany. I don’t remember the name.

In April 1945, shortly before the area was liberated, the Germans put some of us inmates into thirteen railway freight cars and moved us from place to place. When the Americans dropped pamphlets from airplanes that warned they would be bombing the area we were in, the Germans left us at the railway station in the train. All of us were still crammed into the railcars. By chance, I was in car 12. When the bombs fell, half of us were killed in minutes, including everyone in car 13. Everything started to burn, and I had to climb out, but I could only use one hand and got stuck trying to escape. My sister Sara pulled me out from the burning freight car and took me to where everyone was. From there, we all went deep into the forest, where we stayed for about two days and nights.

Then the Germans found us and made us walk for days before they locked us in a barn along the road. During the three days we spent trapped in the barn, I could not eat. I weighed so little, and on the third day I felt I was going to die. I decided to try to leave with my sister to find food. I did not care if I died trying; I needed something to eat. I pried a board off the side of the barn, and my sister and I snuck through. We walked into a field, and at the first house we saw, we knocked on the door. I asked the woman for something to eat and drink, and she came back holding a pot. At that very moment, a man came running, shouting in German, “The Russians are coming! The Russians are coming!” The woman quickly shut the door, and my sister and I made our way back to the barn and told the others that the Russians were approaching. Eventually, we were liberated, around the end of April.

Esther (third from the left), beside her husband, Joseph, with their daughter, Lydia (front, right), and Esther’s friend Helena, her husband and their child (on the left). Munich, Germany, circa 1947.

Esther and Joseph. Toronto, circa 2000.