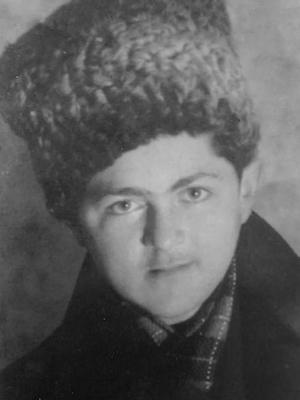

Lou Hoffer

Born: Vijnița, Romania (now Vyzhnytsia, Ukraine), 1927

Wartime experience: Transnistria

Writing Partner: Helena Adler

Lou (Leizer) Hoffer was born in Vijnița, Romania (known in Yiddish as Vizhnitz; now Vyzhnytsia, Ukraine), in 1927. Lou grew up in the region of Bukovina, Romania, which was occupied by Soviet forces in the summer of 1940.

The following summer, German and Romanian forces occupied the region, and in October 1941, Lou and his family were deported to Transnistria. They endured two-and-a-half years under increasingly difficult conditions in the Shargorod ghetto — although lucky to find shelter with a local family, they faced starvation and disease, and were forced to work. Lou and his family were liberated by the Soviet army in March 1944. After spending one year in Oradea Mare, Romania, and close to one year in various displaced persons camps in Austria and Italy, Lou and one of his brothers immigrated to Canada in 1948. They lived with relatives in the small rural community of Hoffer, Saskatchewan, and then in Winnipeg, where Lou worked in a variety of industries. In 1959, Lou married Magda Pressburger; in 1966, they moved to Weyburn, Saskatchewan, where Lou worked in the auto-wrecking and cattle industries and raised a family. In 2003, to be closer to family, Lou and Magda moved to Toronto, where Lou became a speaker at the Toronto Holocaust Museum and got involved in the Transnistria Survivors’ Association. Lou Hoffer passed away in 2025.

Soviet Occupation of Vizhnitz

In June 1940, with the Soviet occupation of Bukovina and Bessarabia, our lifestyle changed completely. Frightening things started to happen. One day we saw Soviet trucks coming into Vizhnitz, truck after truck with what looked like an army. We couldn’t understand what was happening, though the next day we found out that during the night they had rounded up many families, mostly richer families.

Within six months under Soviet control, people who were store owners or had little factories or were involved in other businesses were taken away. My uncle Motie in Chornohuzy was arrested. My dad followed him to the jailhouse in Chernovitz and was allowed to see him once, but soon after he disappeared. We were heartbroken but we thought maybe, within a short time, he would come back. We never heard from him again, and there is no question that he died in a gulag somewhere.

We found out from my uncle Srul, who was in the Soviet government, that the Soviets had prepared three different lists of names of people to be sent to Siberia. We were on the second list. It never happened because the war broke out and Vizhnitz came under Romanian control again.

Under the Soviets it was important to have a job, any kind of job, because those that didn’t were sometimes sent to Siberia. My dad’s job had been to evaluate parcels of forests. He tried to do this work again, but under the Soviets he couldn’t because under their control, forestry was at a complete standstill. So to survive and to stay on the good side of the officials, my dad got a job looking after poultry in a large place. There wasn’t anything else he could do. Soviet methods were foreign to us and we found it hard to adapt. When my dad was given certain orders on how to feed the poultry he realized that they would die with that method. When they did start dying, he gave up the job. He then started to look for other work. We managed to get by because we had a little bit of reserves and we had connections within the villages and of course the fact that my grandparents both lived on the acreages helped.

The positive change in Vizhnitz was the opening of two types of schools. One was a Russian school for upper grades and one was a Yiddish school with six grades. My brother and I both attended that Yiddish school with about two or three hundred students. I was in Grade 6. Everything was taught in Yiddish except the Russian language, which was an hour a day every day. The head of the school was a very nice Russian person who loved the Jewish kids. One other teacher came from Odessa and taught geography. I was happy in the Soviet school, which was superior to the Romanian system. I loved it and I was one of the best students in the school. My marks were at the top. It took me fifteen minutes to get through my exam and a lot of the other students were struggling so I helped them write their exam.

As a matter of fact, the Soviets saw potential in me. This was in late 1940 or early 1941 and, at the Soviet’s government expense, the officials wanted to send both me and a cousin of mine to summer camp when the school year was over for being the top students. I was supposed to leave in June, I don’t remember the date exactly, but because the situation in Vizhnitz got tense I didn’t go and thank God I didn’t. I could have gone and probably just disappeared – who knows where I would have ended up. It was the end of my formal education.

Lou’s paternal family before the war. Back row (left to right): a relative of Lou’s grandmother; Lou’s grandmother Vikie Hoffer; and his grandfather Yehoshua Hoffer. In front, Lou’s aunt Henia (left) and his uncle Zelig (right). Place unknown, circa 1920s.

Lou (Leizer) being held in the arms of his grandfather Yehoshua Hoffer (front; centre). Chornohuzy, Romania,circa 1929.

Lou (left) with his brother Joe after the war. Place and date unknown.

Deportation

Deportation of the Jews from Bukovina and Bessarabia to Transnistria started on September 16, 1941. Late September, early October, it was officially announced to all the Jewish men, women and children in Vizhnitz that we were being deported and had forty-eight hours to prepare and be at the at the railroad station. They didn’t tell us where we were going. I can’t remember what day it was. We had to leave everything in our homes intact and we could take only clothing that we could carry and food provisions for a couple of days. The punishment for damaging any of our property was summary execution. The other thing they said was that people who were incapacitated, sick or too feeble to walk should be put on a stretcher or some kind of flat thing in front of the houses and that the government would take care of them. That morning, my mother cleaned the house, we packed what we could and we got ready to leave.

On the designated day we started seeing families with their bundles walking to the railroad station. We didn’t see anyone else other than Jewish people walking to the station. I remember seeing the religious people – the Vizhnitzer Dayan, a judge of a religious court, who was a highly intelligent, much respected person. My family only had to walk a couple of kilometres to get to the railroad station. At the station everybody hunkered down with their peklekh (packages). A long train of cattle cars and freight cars was lined up at the station.

I was curious to see what was happening in town after we left. I didn’t tell my parents what I was going to do but I walked back approximately one kilometre and I saw that the local population had started looting the Jewish houses. They were carting off everything that was left behind, furniture, bedding, clothes. When I saw that, I saw enough and I returned to the railroad station.

I don’t remember if the Romanian gendarmes who gave us orders were armed, but probably they were. I don’t remember seeing beatings or hearing shots while we were being loaded into the cars. We were more or less packed in but not in an extremely forced way because people obeyed. There were ramps into the cars and I think fifty to sixty people were crowded in. As the train left the station, at around ten in the morning, Jewish life came to an end in Vizhnitz.

At the time I didn’t even think: where are we going and why are we going and what’s going to happen when we get there? The general feeling was that it wouldn’t be so bad, we would find work, and manage. Now that I think back, I believe it was all part of pre-planned propaganda so we would do as ordered.

Inside the crowded car people tried to find a way to sit but not everyone could because there wasn’t enough room. Some people who sat were shoklen zikh (shaking) until they fell asleep. It was uncomfortable, but we kind of accepted it. I don’t remember any sanitary facilities inside the car.

The train stopped approximately two hours after leaving the station. The train had to cross a narrow bridge and they weren’t sure the bridge was strong enough to support the train with us, the “cargo.” We were forced out of the cars and made to walk across that bridge and then we got back into the cars. By the time we stopped five people had died so they made my dad and some other people bury them right at the edge of the river there. I didn’t go to the gravesite but I heard what they did. And then the train took off again.

We travelled the rest of the day and night until around six o’clock in the morning and then the train stopped. Since it was early October, it was still dark. We looked out a little window and saw a forest and we also heard what sounded like the rush of a river. For a while it was quiet and then we heard shooting. The doors to the cars were opened and we were told in Romanian to get out. As we did, I ended up in a ditch in water up to my chest. I was soaked, but I managed to get out. Outside, there were Ukrainians with sacks and Romanians with dogs. The Ukrainians wore distinctive clothes, so we knew who they were. We were lined up five to a row and told to walk in a certain direction. We were very tired and frightened and we didn’t know what was happening. In the distance we saw lights, like lamps, and the gendarmes told us to walk toward it. It wasn’t very far but it was wet and the road was muddy. We walked no more than an hour, but it was miserable.

The lights turned out to be flames from Primuses, gas camping stoves. There had been an earlier transport of Jews from Suceava and they were spread out in an open field. They were a little more prepared, or wealthier, than we were and had brought the stoves with them. When I reached the field with my parents and my younger brother I was so exhausted that I collapsed on some of our belongings and fell asleep. When I woke up I heard something about burying people. It turned out that next to where we had settled in the field there had been a family – a man, his wife, and his mother. The man had been a druggist and he and his mother had taken drugs to commit suicide. I knew what had happened because people were talking about it and I heard what they were saying. My dad said, “We can’t leave them here,” so he and others buried them at the edge of what looked like a little forest. They had just enough time before the Romanian gendarmes came and said we had to line up again in the same formation and walk toward what looked like a small town.

We were frightened, hungry and tired. We did what we were told to do or else they would have killed us. We had no choice. We had no way of resisting.

We walked to the town, which turned out to be Ataki. The Romanian gendarmes told us to take shelter in the empty houses. I didn’t wonder why they were empty, maybe other people did, but to me it was just an empty house. I was once again so exhausted that I collapsed inside. When I woke up a few hours later, around four in the afternoon, I wanted to know what was going to happen so I went outside to find out what other deportees knew. The gendarmes announced that the next morning we had to walk to the edge of the River Dniester where there was a barge that would ferry us into the Ukraine.

In July and August of 1941, the Germans and Romanians had occupied the Ukraine. Romania was given the territory in southwest Ukraine between the River Dniester to the west, the River Bug to the east, the Black Sea to the south and a line beyond the city of Mogilev-Podolski to the north. The area was placed under military administration and renamed Transnistria, which in Romanian means on the other side of the River Dniester.

As I returned to the house where my family had taken shelter I noticed written messages on the outside of the houses. One said: “We are being killed. If you come by here and survive please say Kaddish[the mourner’s prayer] for us, tell the world what happened to us and don’t ever forget us.” Everywhere I looked, the same message was written in Yiddish and Romanian, inside and outside of houses with mezuzahs on their doorframes. The Jews of Ataki had been killed. These messages got etched in my brain and are still there. I’ll never forget them. Even though I read these messages, I didn’t fear for our lives. We didn’t know our fate; we thought that we’ll go over there, find work, something. I didn’t know.

The next morning we walked to the River Dniester and we were loaded into a large barge. We were tightly packed in and there were also some German soldiers. There were so many people that the water rose to approximately four inches from the top and I was afraid that we’d drown, but we made it across with our belongings. There was a cable that was used to pull us across the river and we got off the boat in the late afternoon. As soon as we crossed the River Dniester to the Ukrainian side, we were in the territory of Transnistria. We were now stateless, homeless and we didn’t know what to do next.

Transnistria was the area that Jewish deportees from the Romanian provinces of Bukovina, Bessarabia and the northern regions of Moldova were forced to resettle in, to de facto ghettos that were called “colonies” by the Romanian government and that I call Lagers (camps). The Romanian method for annihilating Jews was for the most part different from the Germans’, although there were mass murders and pogroms in certain parts of Romania. The difference was that in transporting Jews across the River Dniester and letting them fend for themselves, I think they believed that we wouldn’t last very long. The aim of the Romanian fascist government was to send us there to die.

As soon as we crossed the River Dniester to the Ukrainian side, we were in the territory of Transnistria. We were now stateless, homeless, and we didn’t know what to do next.

Surviving in Shargorod

The first winter, we adjusted to living in Shargorod. Our background, being born and raised among the Ukrainian people and being close to agriculture and thus being a little bit harder, sturdier, perhaps of a stronger fibre, meant it wasn’t strange to us. The only strange thing was that we were in a different country but we knew what it was like to struggle. Jews were not allowed to leave Shargorod so it was like a ghetto. The Ukrainian peasants would come into town once or twice a week with their wagons filled with a lot of different food like potatoes, different kinds of grains, milk and cheeses, and go to the marketplace. The marketplace was a road lined with stalls with peasants on each side. If a peasant woman had milk to sell, she would sit down on the ground or on a stool with the milk in front of her and if you wanted a quart of milk you would ask what she wanted for it and she would tell you how many marks it was. Most of the time, products could only be obtained for money, a kind of German mark for currency called Reichskreditkassenschein (RKKS). In this part of the market peasants sold small things like fruit and vegetables; outside there were wagons with things like sacks of flour and potatoes. There was a large sugar plant near Shargorod so there was lots of sugar and it was cheap; salt was scarce. I don’t remember exactly how much a glass of salt cost, but you could probably buy fifty kilos of potatoes or more for the same amount.

Bartering was the way to get something you wanted for something that you had. If you had a suit, and a suit was very desirable, and you wanted a sack of flour for it, you would display it at the market. A peasant who wanted it would ask what you wanted for it and you might come to an agreement. You were happy to go home with what you had bartered for and the peasant was happy with getting what he wanted. We Romanian deportees were the foreigners, with foreign goods that the Ukrainian peasants wanted and were very willing to barter for. They didn’t have the things we did; they liked our clothes, our sweaters, our shoes. We had bed sheets that were desirable, some women’s skirts or clothing, the normal things. We couldn’t bring a lot to begin with and what we brought didn’t last very long. We bartered away everything we had. Some people bartered away their shoes and then they had to wrap their feet in schmattes, rags. As long as you had things to barter, you could survive.

We bartered for potatoes, flour to bake bread, basic things. I don’t remember buying cheeses but there was some kind of yogurt, I think they called it kallatoucha, and that and milk were the staples of our diet. We adjusted to the reality that food was going to be scarce and we would not have enough; as long as you had desirable things to barter, you wouldn’t starve. Extreme hunger started a year later but during this time we were still often hungry. The local Jewish people of Shargorod were faced with the same struggle to survive as us but they didn’t have foreign goods to barter with that the Ukrainian peasants wanted; they had the same possessions as the peasants.

As time went on and people bartered away most or all their belongings, starvation started to set in. People who couldn’t speak the language or were too old or too young or didn’t have any agricultural background started to die very quickly. In summer, we saw wagons loaded with the dead and in the winter, the sleds. There was no end to it. People faced malnutrition, starvation, dysentery, typhus. Every second or third day, people collected the dead bodies.

During 1942 and 1943 our situation got desperate. We got to the point where we didn’t have anything to eat and we faced either starvation or making the decision to sneak out of the ghetto. Sneaking out wasn’t difficult because there were no fences or guards to keep us in. The danger was if you got caught – your survival depended on who caught you. If it was a Romanian soldier and he suspected you were a Jew and he was a reasonable human being, he would give you a good kick in the pants and tell you to go back to Shargorod; if they felt like it, they would beat you up or kill you with a rifle.

Because my family had experience with farm work and being among peasants and, as I mentioned, could speak Ukrainian, we had an advantage. We weren’t like the sophisticated urban type; we were more of the common people. In 1942, my brother was fourteen, I was fifteen, my dad was forty-four and my mother was thirty-eight, so we were young and strong enough to able to fight for survival. I can’t fully explain it but we did fight; we didn’t give up.

Lou Hoffer with his Sustaining Memories writing partner, Helena Adler. Toronto, 2013.

Lou and Magda’s wedding. From left to right: Lou’s younger brother, Sam, friend Sam Helman, Magda, Lou, and Lou’s parents, Sali and David. Winnipeg, 1959.