David Jacobs

Born: Tomaszów Mazowiecki, Poland, 1918

Wartime experience: Ghetto and camps

Writing Partner: Marlene Chandler

David Jacobs was born in Tomaszów Mazowiecki, Poland, in 1918. He grew up in a religious family with four brothers and two sisters.

He trained at a young age to work as a tailor. When the war began, David fled to Warsaw, but soon returned to Tomaszów Mazowiecki, where he lived in a ghetto after it was established in 1940. From 1943 until his liberation in April 1945, David was in both forced labour camps and concentration camps, including Auschwitz. He was liberated near the Buchenwald concentration camp in April 1945. David met and married Lily, also a survivor of Auschwitz, in Germany after the war, and they immigrated to Canada together in 1947. In Toronto, they raised a family. David Jacobs passed away in 2016.

David. Tomaszów Mazowiecki, Poland, circa early 1930s.

David’s family before the war. David is standing in the back row, far left, with his mother, Chana, and father, Toyvia, beside him. Poland, circa late 1930s.

David executing a high jump. His younger brother, Haskel, is in the white T-shirt in the background. Tomaszów Mazowiecki, Poland, circa 1938.

People didn’t resist. If you resisted, they just gave you a bullet.

The Chaos of Invasion

I grew up in Tomaszów Mazowiecki in a religious home, but whenever I could skip synagogue, I did. Our home was kosher, and we observed Shabbat, which I also didn’t always like and would also skip whenever I could. I was a bit of a rascal! I always looked forward to the end of Yom Kippur. We were supposed to go to shul for the whole day, but I of course escaped to my home with my friend before the service was over. The door to our home was locked, and we couldn’t eat, but I would break in anyway.

My younger brother, Haskel, liked school very much, was a very good student and wanted to be a doctor. He was first a tailor but then went to school to learn how to be a doctor. My oldest brother, Noah, was a tailor of women’s clothing. The next eldest was Naftali and he looked after the taxes for my parents’ property. His eyes weren’t good though. My other brother, Beryl, was born sick and never became well. He was very ill and couldn’t even go to school. Near the beginning of the war, the Nazis took him away and beat him to death. He didn’t know that he had to stay in the house and had been caught outside. I also had two sisters; Slova, the oldest, still lived at home, as did the youngest, Chuma.

I grew up in a mostly Jewish neighbourhood, and all my friends were Jewish. I knew many Polish people too, but we were not friends. Most of the Polish people were antisemitic. They always said, “Żyd, Żyd (Jew) is coming,” when they saw a Jewish person. I went to school only with Jewish kids.

It was terrible to be Jewish in Poland, but before the war started, I never felt unsafe because I was Jewish. I do remember one time as I was walking on the street in my hometown, Tomaszów; three boys were waiting for me and one of them jumped out and punched me in the face. I didn’t even hit that guy back. I walked on and got away from them, though. I was fast. My brother Haskel was more aggressive than me – if some Poles got to him, he hit them back.

***

When we first heard of Nazis invading Poland, we, like many others, fled to Warsaw, which was about 120 kilometres away, because we were afraid. I was in Warsaw when the war first broke out. I was twenty-one years old and, like everyone else that age, drafted to the army. I was running around Warsaw saying, “I want to fight for Poland!” I was so stupid. I saw a friend of mine who was wearing a Polish uniform and asked him to show me where he had gotten it. I went there and right away they asked me, “Are you Jewish?” When I said yes, they said they didn’t need me. At that time, the Germans were still fighting to get into Warsaw, bombing from their airplanes. Soon after, the Nazis took over anyway.

In the beginning, I had felt it would be safer in Warsaw. Nobody knew where it was safe to go though. Who knew where you could be safe? I stayed in a little synagogue. I slept there with other Jewish people before returning to Tomaszów.

I worked with my brother as a tailor when I returned to Tomaszów from Warsaw, until they made the ghetto. In December 1940, when the Germans announced they were establishing ghettos in Tomaszów, I went with some false papers to Warsaw to buy some fur. I will never forget this, never in my life, that I went to Warsaw and into the ghetto. A streetcar went into the Warsaw ghetto and turned around and went back out; they didn’t want the Jews to go in and out of the ghetto, but I had to take a chance. I remember going on the streetcar, which just slowed down but didn’t stop. I’ll never forget. Two Germans were sitting on the streetcar but they didn’t do anything to me. I jumped off the streetcar and I was in the ghetto. After two or three days, I bought some fur from the guy who, before the war, used to sell fur in Tomaszów.

Then, the same way I had snuck in, I had to sneak back out of the ghetto. A Polish guy told me to come with him to a house. He asked me what I had with me and I said I had nothing. He wanted to take my fur away from me and I said no, I wasn’t going to give him my fur. I didn’t give it to him but he ran after me. I finally wound up somewhere outside, where I slept. When I awoke, I started to walk back to Tomaszów. In Warsaw, in the ghetto, I had seen people playing music and dancing and trying to enjoy their lives despite being in the ghetto.

In Tomaszów, the street we lived on became part of the ghetto. There were Jewish and German tenants inside at first, before all the Germans left that area. Early on when we were living in the ghetto and had to go do forced labour, one German sometimes helped us with food, giving us a little extra. But I also remember when a German all of a sudden pulled the trigger of his gun, far away from us but on the same street, and the bullet hit my uncle who was staying with us, and he was killed. There was no reason; my uncle was murdered because he was Jewish. We were wearing yellow stars on our clothing then, and my uncle was in the street and was shot from far away. It’s very hard for people who didn’t go through this to understand. It’s hard to understand all of this. I was just lucky to survive, that’s all.

Although for a time I had been living with my brother outside the ghetto, eventually everyone had to move inside the ghetto. My brother and I took the sewing machines and joined my parents and other family members who were already there. Everybody, including all our relatives from other towns, came to us because we had a big property, where, prior to the ghetto, we had lived comfortably.

***

My sick little brother, Beryl, had already been sent away to Lublin about half a year earlier. They then sent him to Piotrków, and my parents got a letter saying he had died. My mother and father went by horse and buggy to the funeral in Piotrków, thirty kilometres away.

When the ghettos in Tomaszów were disbanded, I was one of the last people to leave. I was left with my brother Noah and my sister Chuma. I remember the last time I saw my parents; it was at the little church in Tomaszów. There were probably a few hundred or a few thousand Jewish people left at that point. Before entering the church, the Germans “selected” where each person should go. Some went inside the church, and others were sent in other directions. The guards pointed their finger in one direction or another. People who worked, like my brother and me, were chosen to go into the church. They sent other people to a school with a field, and those people stayed there that night and were then sent by train to the Treblinka death camp.

That was the last time I saw my parents, and it is my most painful memory. I was just lucky that I had a paper stating I worked in a shop. That paper saved my life.

David and his younger sister, Chuma. Place unknown, circa 1946.

David (right) with Moishe Schwartz in Bergen-Belsen, Germany. Circa 1946.

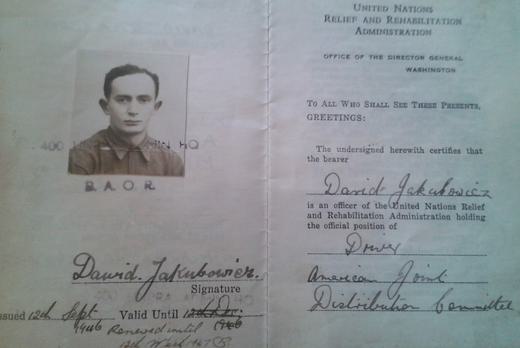

David’s identification certificate from the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), issued September 2, 1946.

The Terror of the Camps

We knew about the Nazi policy toward the Jews. We knew that they wanted to get rid of us all. We knew by how we were treated, before 1942. We saw them killing Jews in the streets. People didn’t resist. If you resisted, they just gave you a bullet. I remember this happened to many people. I don’t even remember thinking about escaping.

I knew all this before I was sent in the spring or summer of 1943 to Bliżyn, a forced labour camp in Poland, where we had to work and wear uniforms. One guy there, from Germany, was the lead tailor. He was not a bad guy. I saw him after the war when I went to Germany. The head of the Nazis in Bliżyn though, a man named Paul Nell, was horrible. Nell went everywhere with a dog named Pasha. I remember that dog well. When Nell wanted the dog to bite me, he said, “Pasha, bite the Hund (dog).” I was the dog, and he was the human! After the war, Nell was captured, and there was a trial in Hamburg, Germany. I went with my daughter. At the trial, they asked if any witnesses wanted to ask questions, so I asked him what the name of his dog was. He didn’t say a word though. Nothing.

Once at night, maybe midnight, Nell came into the shop where I worked, and I was asleep. The dog almost attacked me and somebody else from Tomaszów, but everybody stood up immediately; we jumped up and said hello. I was just lucky. That dog would have really hurt me. I remember once they brought in a guy who had escaped from the camp, and before shooting him they let the dog attack him. In Bliżyn, everybody was afraid.

I was lucky to be able to play soccer in Bliżyn; the Germans allowed it and would watch us. For example, people from Tomaszów would play those from Radom. We always won. After the game, the head of the Jewish police, the kapo Slavik Minsberg, made arrangements for us to go in the kitchen to get something to eat. A lot of people from Tomaszów worked in the kitchen, mostly because we were some of the first people sent to Bliżyn. They then sent people from Radom, Bielski and other places.

I experienced a lot of hunger in Bliżyn. Some others brought money with them right from the beginning to exchange with the Polish people for food, who stayed outside and tried to exchange things with us.

After about a year in Bliżyn, we were taken to Auschwitz concentration camp. I was with my brother Noah, and my sister Chuma was also sent to Auschwitz. It took us a long time to travel from Bliżyn to Auschwitz. We stopped at every camp and they were full and we had to wait to get a call to tell us where to go. The train stopped and picked up people on the way. I remember we stopped in Oranienburg in Germany and some other camps and other towns.

When we first got to Auschwitz, we didn’t know where we were. Finally, we found out. In Auschwitz, it was impossible to know if we would be alive the next day. I don’t think I had hope; I don’t think anyone had hope. I remember a Jewish man named Pinkus, from Paris, who was the head of our barracks. Some of the Jewish kapos were terrible. They thought they were going to live longer. Pinkus was a murderer. Everybody remembered him. When he asked me, “What do you do?” I told him a lie. I said that when the war broke out, I had been a cook in an area near where Noah used to live, a big area where the rich people had lived. Pinkus said, “You’re going to cook for me.” I was happy. I said, “What do you want me to cook and where shall I get it?” He lifted up his stick and said, “You said you’re a cook, and you’re asking me where you should get it?” I then understood that I should “organize” (steal) it myself. I didn’t know a thing. I didn’t know anything, but I figured out fast that I was not to ask any questions.

***

When the Allies started to move into the area, we were sent from Auschwitz to a Buchenwald subcamp in Ohrdruf, Germany. Little by little, we found out that the German soldiers were all being sent to fight the Allies. It was about three days at least by train to get to Ohrdruf, which had been a camp for German soldiers near the city of Gotha.

I was a cook, again, at this camp. I still remember a German-Jewish guy named Natan. They needed some cooks because we had just arrived, and I said that I was a cook. Natan mentioned this to someone, and that was how I was selected to be a cook. I knew him from Auschwitz but had never even had a conversation with him. It was always a good thing to be chosen as a cook. You had to eat, and of course we were around the food. Every morning I filled three canisters with soup for the people from Tomaszów.

I had a friend from before the war who I had gone to school with. In the first camp in Bliżyn, he was a cook – the head cook. But he acted as if he didn’t know me and didn’t help me. That made me feel terrible. So when I was the head cook in Ohrdruf, every day there were three canisters of soup for the people from Tomaszów. I risked my life. Every morning, they picked it up and they ate together.

One time, I told my friend Itzhik, “At least you have something to eat.” He said that if I can’t help him in any other way, he would have to hang himself. So I said come on, and I took him to work in the kitchen with me. After the war, we were liberated together. He eventually married a very nice-looking girl from Białystok, Poland, and they went to Paris because she had a brother somewhere in Los Angeles and could get there more easily from Paris. I visited them in Paris, but later, in Los Angeles, something must have happened to him. I don’t know why, but he hanged himself there.

Ohrdruf was about sixty kilometres from Buchenwald. The Nazis put a grave about two kilometres long in the Ohrdruf camp, and every day they brought dead people. I myself did “work” in that grave. The Nazis brought trucks filled with the bodies of dead people from Buchenwald. It was not too far away.

***

On April 4, 1945, I was liberated in Ohrdruf by the Americans. We didn’t know that we had been liberated. Our camp was transferred to Buchenwald. My brother, my friend Itzhik and I started to walk. We didn’t know anything. We walked and walked and wound up in a place where we could sleep. When we were liberated, something interesting happened that I will never forget. It was at nighttime. We slept over in a camp — not a concentration camp — and there were some civilian workers there. In the morning, I saw through the window a motorcycle with two German officers. One German stayed on the motorcycle, and the other one came into our room and asked us how we got there and if we had seen any Americans. Who could dream about this? We said no, which was true. A guy from Częstochowa asked him for a cigarette, and he gave it to him.

I think the Germans had it in their mind to send us to Buchenwald. One German opened the door and then he closed it! There were a lot of us there, including my brother Noah and our friend Itzhik. We didn’t know where we were. Finally, we opened the door, and there was no one around. We then saw a Polish man, so we asked him where we could go to get something to eat. He showed us where to go, so we went there, still on our own.

I said, “We have to go to look for Americans.” We walked a few kilometres and all of a sudden we saw some Americans and their army trucks. With us were two Czechoslovakian boys. We couldn’t believe it. The Americans came out to greet us. They assumed we were hungry, so one of them went into his vehicle and brought out some bread. I asked what kind of bread it was, because it was white and spongy; I had never seen bread like this. In my knapsack, I still had some bread and took my bread out and gave it to him. That was something I will never forget.

Then my brother, our friend and I stayed in Ohrdruf for a few days, but there wasn’t much there so we decided to move to another city. We went to Gotha and rented a room there from German people. I don’t remember how we had money even. We went out on the street, saw Americans, and they heard us speaking Yiddish. They understood what we were talking about because they were Jewish people! They didn’t speak the language as well as we did, but they knew some Yiddish. Anyway, one of them worked for General Eisenhower, who was in charge of the American army. He stopped us and said to me, “I have a job for you.” He said that he would put me into a store and all I had to do was watch the Germans come in and take off their clothes and put on civilian clothes. I was to report about this. I didn’t really understand what I was doing this for. I did it though.

You should have seen the Germans in that store. They didn’t know what to do for me. Whatever I wanted, they gave me.

We wondered about our sister Chuma. About three or four weeks later, I wanted to go look for her. So, the owner of the store where I was working took me up to his office. He was a nice German guy and started to ask me questions in German. Our languages are similar, so I could understand some. Finally, he took me down into the basement and unveiled to me a brand-new car. It was an Adler. He had a chauffeur. He also had a Mercedes. When he unveiled that Adler, he said, “To you, this possession.” The car was for my use. He gave it to me as a gift! I told him that I didn’t know how to drive. He said, “Okay, we will go find my driver and he will show you.”

The driver gave me some instructions, but I still didn’t know how to drive. I started to drive that car without knowing anything at all! Then an American convoy came along, so I had to stop. Then I tried again, and my brother and friend saw me and asked if I was crazy! I said I didn’t know. I had to reverse and didn’t know how. There was a beautiful fence, and my brother and Itzhik had to demolish the fence so I could get through. Somehow, I figured it out and learned how to drive.

The American soldier who helped me get the job told me he’d help me find my sister and supplied me with gas, no charge. My brother Noah replaced me in the store. I didn’t find my sister in Germany. I went to all the camps. Finally, I went to Bergen-Belsen. There were a lot of people there from my town, and when they saw me they asked me how I got there. I told them about the car, and they were amused and bewildered about it, wondering how I got a car already.

I stayed at Bergen-Belsen for a short while. I then saw a man who had come from Poland who had seen my sister Chuma, so I decided that I had to go look for her there. I couldn’t go with the car even though I did have papers. Anyway, I went and found my sister in Poland.

I wore an American uniform after the war. I was with the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (the Joint), and a man named Mr. Wadlinger, a Canadian, got a military entry and exit permit for me. He went to the headquarters in Berlin. He brought me down and gave me an American uniform. Everyone saluted me. I went all over Europe – Paris, Brussels – and it didn’t cost me anything.