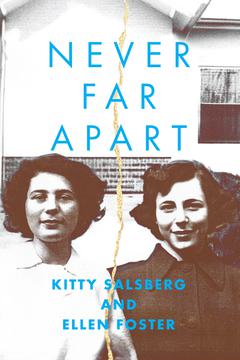

Never Far Apart

In the Dark

Ellen:

One day I no longer had to go to school and I no longer had to be afraid of the neighbour lady. In June 1944, a law was passed that all people who were Jewish had to move into segregated apartment buildings that were only for Jews. My mother had already sewn a yellow star on my coat, and we walked to another building, where to my great delight I found my uncle Latzi’s wife, Serena, and my cousins Hedi, Imre and baby Gyurika. Hedi, like her two brothers, had blue eyes and blond hair. She and I had lots of fun playing together every day. Every so often my aunt Margaret came over with some food, and one day she even brought my sister, Kati, who was never as much fun to play with as Hedi and Imre. My mother looked so happy when she saw her, and I was happy too.

What more could anyone ask for? I had my best friends playing with me every day, I never had to go to school and my mother was always at my beck and call if I needed her, because living in this new place she never had to go out, so she never left me alone in the apartment. It was a dream come true.

Soon enough, the dream turned into a nightmare. All the grown-ups became very upset. They started to pack everything they had into one suitcase. My aunt Serena sent word to her husband that our building was to be evacuated and everyone who lived there was going to a new location. My mother, too, was troubled. She did not say anything, but I could tell. To my surprise, my uncle Latzi showed up, bringing my sister with him. He said that he would take us children with him and keep us safe. I was torn from my mother and we left, walking in the darkness to a place where children were supposed to be safe.

Uncle Latzi took us to a building that had a sign with a red cross. I knew about the Red Cross. They helped people. After my uncle left us there, our heads were shaved so we wouldn’t get lice, and we were shown where we could sleep on a mat in one of the large rooms, with lots of other children. We were also given something to eat, though I don’t recall what. All I remember is being hungry. But I wasn’t too scared, because my sister was with me, and I knew that she would make sure that I was safe. We must have been there for at least a few months. Hedi looked after her brothers, and I stayed by Kati’s side all the time. It was cold there, but not as cold as outside. When it was dark, and even in the daytime, we huddled next to each other on the mat to keep warm. I don’t recollect anyone playing or singing, but some of the children made scary sounds from their throats because they were deaf. I had warm enough clothes on, but my shoes had holes in them, which my mother had covered up on the inside with cardboard. This didn’t matter to me until we were made to walk outdoors when men with guns came to the building. They were angry looking and had sharp bayonets attached to these guns, so they could both shoot and stab with them. The sight was threatening and frightful.

We all lined up outside in the dark. A Red Cross nurse told Hedi that she could hide our baby cousin because he had blue eyes and blond roots, he wasn’t circumcised and he hadn’t yet learned to talk. Hedi trusted this lady, who seemed kind, although she was a stranger to us and we never even knew her name. The lady went away with Gyurika before the soldiers could see her. Then we were marched away from the building of safety, going where, we didn’t know. I held on to Kati because I had a hard time walking. The cardboard covering one of the holes in my shoes let in the slush, and when the snow stuck to it and froze, it made that shoe higher than the other. We could not stop to scrape off the ice. Hungry, scared and freezing, I marched alongside my sister, limping as if I had one leg longer than the other.

Kitty:

It seems that members of the Nazi-approved Arrow Cross Party had decided to march us children into an enclosed area called the ghetto. The Budapest ghetto was established on November 29, 1944, in the last months of the war, when Germany and Hungary were in a life-and-death struggle with the Allies. Nevertheless, even in those desperate times the Nazis were still determined to finish the job of killing all the Jews of Europe in a process called the “Final Solution.” To that end, they collected all the remaining Jews of Hungary, those not in hiding or protected by some neutral government like Sweden, and placed them in an area separated from the non-Jewish population. Guarding them with armed soldiers, enclosing them within stone walls and fences, the Nazis made sure that no food could go in and nobody could come out. By keeping the Jews completely cut off from the world, it was easy for the Nazis to continue moving large, defenceless groups of people from this holding tank of misery to slave labour camps, where the Jews were used, if capable, for providing much needed labour that would free up men in the general population to be soldiers.

The people remaining inside the ghetto received no humanitarian services. Surrounded by garbage and excrement, crowded together, the starved and weakened children and the elderly easily fell sick from typhoid and other diseases. Many died horribly. They were left out in the streets, or in areas not as plainly seen.

After Ilonka and I were shown to an apartment in a building, we stayed inside with one group of children, huddling because of the cold. Hedi and Imre were separated from us and put into another apartment, and I lost sight of them. Years later, I found out that my cousin Imre had decided to explore his unfamiliar surroundings. As he walked into a bombed, half-destroyed stairway, he stumbled and fell on top of a dead man. I don’t think he ever got over it.

I was aware of the scary situation we were in, but unlike Ilonka, I did not feel scared. In fact, I did not feel much of anything at all, except cold and hungry. As I lay beside Ilonka, I thought of all the food I had refused to eat when my sweet and caring mother had tried to get me well, but I did not think of my father or my mother or my aunt Margaret being marched away, possibly to their deaths. I just daydreamed about food and wished that it could be warmer in the apartment in the middle of a harsh December.

I hunted around the apartment and found a closet full of abandoned clothes. Since we had no blankets, I put on layers of them and went to sleep. In the middle of the night, I awoke with a terrible itch all over my body. When daylight came and I looked at the clothes I had found, I saw they were full of bugs and eggs. That is when my feelings broke through. On my own, without adults, degraded by the filth and by the bugs that attacked my body, I bowed my shaved head in despair and started to sob uncontrollably. Then I had to stop so as not to frighten my already terrified sister.