Tracks in the Snow

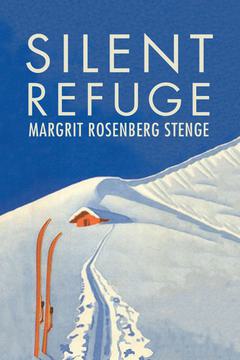

Silent Refuge

Our stay with the Granlis came to an unexpected and abrupt end. In March 1942, the lensmann paid us a visit with some very disturbing news. A German raid of the villages in his district was imminent, and he urged us to leave for Buahaugen immediately. Travelling to Buahaugen at this time of year and with no advanced planning was a terrifying prospect. We did not know how we would manage all by ourselves or how we would get all the necessary provisions. Nils promised to look for someone to bring us what we needed at regular intervals, and we had no choice but to believe him. So on a bright, sunny day, we set out on skis with one of our neighbours, each of us carrying as many supplies as we could.

It took several hours of skiing through deep and heavy snow to reach the seter, but since there were four of us, we made deep tracks in the snow. We hardly recognized Buahaugen when we arrived — the landscape looked like it was frozen in time. Our neighbour helped us carry wood inside and start a fire in the fireplace and the stove to warm up the cottage. And then he left. We were all alone in the great expanse of snow and ice.

The brook was frozen, too, except for a small opening, where we were able to fetch drinking water — on skis, of course. When we needed water with which to wash ourselves and our clothes, we melted snow in a large pot. At night, the cottage got freezing cold, and it was usually my mother who got a fire going before my father and I arose in the morning. We could not go outside without putting our skis on. It was almost inconceivable that we could stay here all alone until the farmers came up for the summer. But that was what we did — at least that was what my parents did.

After a few days in the mountains, I did something that was probably the most selfish thing I have ever done in my whole life. My only excuse is that I was only thirteen years old. I told my parents that I wanted to go back to Rogne, to stay with Nils and Alma and to go to school. Their reaction was predictable. I was their only link to the village in the event that something happened to my father, and now I wanted to leave them completely on their own. In the end, they let me go, provided that I agree to return to the mountains every weekend with provisions.

So I set out on my skis, retracing the tracks we had made a few days earlier. I felt free as a bird — for a little while. Then I began to realize that I was now all alone in the great snowy expanse I had to cover. What would happen if I fell and could not get up?

Silent Refuge, Margrit Rosenberg Stenge

In 1940 in the remote village of Rogne, Norway, eleven-year-old Margrit Rosenberg and her parents believe that they have finally found the safety that has eluded them since fleeing from Germany two years earlier. What could go wrong in a tiny village? But after war breaks out in Norway and anti-Jewish persecution escalates, the Rosenbergs must spend their winters in an even more secluded refuge – a small, rudimentary cabin in the mountains accessible only on skis. At first, in a landscape frozen in time, the isolation offers relative security and tranquility. But two years later, as the Nazis begin to arrest and deport the Jews of Oslo, the Rosenbergs are forced to make a fateful decision to trust the Resistance and plan a dangerous escape from Nazi-occupied Norway to neutral Sweden.

Introduction by Robert Ericksen

- En bref

- Allemagne; Norvège; Suède

- Fuite

- Clandestinité

- Norvège d’après-guerre

- Immigration au Canada en 1951

- Ressources éducatives disponibles: Margrit Rosenberg Stenge

À propos de l’autrice

Margrit Rosenberg Stenge (1928–2021) est née à Cologne (Allemagne). À la fin de la guerre, elle retourne vivre à Oslo avec sa famille et se marie, avant d’immigrer au Canada et de s’installer à Montréal en 1951 avec son mari Stefan. Margrit a travaillé durant quarante ans dans diverses administrations, après quoi elle a traduit six livres du norvégien à l’anglais, dont Counterfeiter: How a Norwegian Jew Survived the Holocaust de Moritz Nachtstern (2008).