Simon Saks

Born: Będzin, Poland, 1932

Wartime experience: Ghettos and camps

Writing partner: Sandi Cracower

Simon Saks was born in Będzin, Poland, in 1932. After the German occupation of Poland, Jews in Będzin, including Simon and his parents, faced increasing violence and restrictions, leading to segregation in an open ghetto.

In 1942, Simon’s father was sent to a forced labour camp, where he perished. Over time, Jews in the Będzin ghetto were resettled into smaller areas nearby, and Simon and his mother were moved to the Kamionka ghetto. As deportations to camps increased, Simon and his mother hid, but his mother was found and deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where she was killed. Simon’s uncle David, a foreman in a factory, hid Simon and then took him to work at an army base. In the summer of 1944, Simon and his uncle were sent to a forced labour camp called Annaberg (Góra Świętej Anny, Poland), and in the fall they were sent to Blechhammer (Blachownia Śląska), a subcamp of Auschwitz. In January 1945, the Blechhammer camp was liquidated, and Simon and other prisoners were sent on a death march; they walked for more than a week to the Gross-Rosen concentration camp. Days later, Simon was sent to Buchenwald; he was kept there for a few months before being put on a cattle car that eventually took him to Czechoslovakia, where he was liberated. In September 1945, Simon and a group of other young orphans were brought to London, England, where he lived until immigrating to Canada in 1948. In 1952, Simon started his own clothing sales company in Toronto. He married in 1954 and raised a family. For a long time, Simon chose not to speak about surviving the Holocaust, but after returning to Poland in 2011, he changed his mind and began speaking to and educating young people, and then decided to write his memoir. Simon Saks passed away in 2018.

Growing Up Fast

As a child during the war years, I realized I had to think like an adult. I knew I had to do what I had to do. I had to grow up fast. I felt that there was something special about me, and I knew I had to use all my resources in order to live. One day I pointed my finger upwards and looked at the sky, saying, “I’m going to survive.” I wasn’t religious; it wasn’t about God. When I went to synagogue with my father as a child, in a way I became religious, but when I saw all the horrible things that took place later, it bothered me a lot, and I said, “If we have a God, why did He let this happen?” When I thought about that, I couldn’t believe in Him. I was just determined to survive, and I did.

When I was eleven years old, living in the Będzin ghetto, I took a huge risk. My uncle the furrier, who lived with us, had made a fur coat for a Polish woman and she was very happy with it. She wanted to pay him with groceries, but she couldn’t come into the ghetto to bring them to him, and he couldn’t leave. I offered to go out to pick up the food, to take off my yellow star and go. I made it to the Polish lady and she said, “You’re okay. You don’t have to worry about wearing your star. You don’t look like a Jew.” I was safe and successful in bringing back the food for my family, so I did it again. Then I heard that if a Jew was found not wearing his Jewish star, he would be shot on the spot. I never went again.

***

From the spring of 1942 to the spring of 1943, things really started to heat up. I had to hide all the time with my mother and grandparents. We were in bunkers, basements and secret rooms. My mother knew a lot of people and places, and now that my father was gone, she always took me with her. Sometimes we had to go somewhere different every night because the Germans were searching and grabbing people. If they found your hiding place and you didn’t come out, they would just shoot you.

The Germans also decided to round up all the Jewish men with beards and payot, sidelocks, and have their beards shaved and their payot cut off. Once, I was standing near one of these roundups when suddenly an SS man came up to me and gave me a stick. He told me to go and hit the man whose hair was being cut, an Orthodox man with tsitsis (knotted fringes on the four corners of clothing) and payot. I said, “I can’t do it.” You know what? Nothing happened to me. That Nazi could have done plenty, but he didn’t touch me. He got somebody else to hit the man. I refused to do it. I was a brave kid.

One day in late 1942, as the Germans prepared to close parts of the Będzin ghetto, they moved us into even smaller houses at a higher, more remote location where it was easier for them to guard us. This second ghetto was called Kamionka, and we stayed there for about six months. It was not far from where the synagogue had been. Originally, some Jews had lived in the Polish neighbourhoods of the town, and vice versa, but when this new ghetto was created, Jews were moved to live there and the gentiles were moved out. Jews were also brought in from many small German towns, and we were all squeezed together into very tight quarters. My family lived in two-and-a-half rooms — a bedroom, a kitchen and a dining space.

In Kamionka, we couldn’t take the kinds of risks I had taken in the first location. This ghetto was more closed in, making it more difficult to escape, and if the soldiers thought someone was hiding somewhere, they shot their machine guns right through the door or threw in grenades. The soldiers began to crack down on anyone caught trying to run away by shooting them in the most terrible way. They used dumdum bullets that expanded as they went into a person, ripping them apart. I witnessed all this as a child, and I cried. I saw those bodies in the street, torn apart. I looked at them and I can still see them. What the Nazis did was horrible, but I could see, even then, that I couldn’t even think of being afraid. I had to do things that I knew I wouldn’t be able to do if I was scared. I knew I had to take care of myself. I wasn’t afraid to talk to the Germans, which I had proved when I refused to hit the Orthodox man with that stick.

One day, my grandfather went into hiding. I didn’t know where. My mother took my grandmother and me and hid us in a shed. Inside there was a lot of furniture piled up to the roof, and my mother put us into a little cabinet, but she did not hide with us. My grandmother and I could hear the soldiers searching for us and we remained quiet. We stayed there for at least four or five hours, and when we came out my mother was gone. She had been taken. The SS had put her on a train to Birkenau, in Auschwitz, and that’s where she died.

This was June 1943. Shortly after, my uncle David, the factory foreman, came to me and said he’d heard they were taking all the Jews away to Birkenau, and that night he took me to hide in the factory with many others. We hid where all the fabric was stored and stayed there for a week or more. Over three of those days, the Germans took most of the Jews from the ghetto to Birkenau, although several hundred were held back. Their job was either to work in the factories or to take all the clothes and luggage from the abandoned Jewish houses and pile it up in a former Polish army base, a big building the Germans had taken over. These Jews were also forced to find all the dead bodies and put them on wagons. Ultimately, these Jews who had picked up all the bodies were sent to Auschwitz, too. Even my grandparents, who had been in hiding, were discovered. My grandmother was sent away, but as my grandfather was being taken, he suffered a heart attack and died. He would have died in Auschwitz anyway.

It became my job to work with those who had to sort all that clothing at the Polish army base. I was the only kid there. One day the Wehrmacht came and took forty of us to do some cleaning outside. In the afternoon the soldiers marched us back to the base, and as we approached, I saw the SS driving up. I knew that if they saw me, they would grab me right away and shoot me, because that’s what the SS did with kids. Suddenly, a soldier from the Wehrmacht came to me and said, “You, get out of line. Go and hide in that little forest back there. Hide behind that tree until you see the SS drive away. Don’t come back while they’re here.” I obeyed. I knew then that I had to think like a man, someone who knew things. I couldn’t act like a child. I considered what I should do and thought maybe a Polish family might take me in. But I hated the Poles because in my mind, they were all antisemites, so I knew I couldn’t do that. Besides, I had told the soldier I would go back, so, after the SS left, I did.

I’ve always been sorry I didn’t get the name of that Wehrmacht soldier. He really saved my life … he saved my life! After that, we were all sent away, my uncle and I included.

The ghetto period was the worst time for me. It lasted three and a half years, and in my mind, that’s where the most terrible things happened. That’s where, as a very young child, I witnessed people being killed all the time and others being taken away on trains. That’s where I lost my mother, my father and my grandparents.

Saved Again

The next place I was sent to was Blechhammer, a subcamp of Auschwitz. We arrived wearing regular clothes, but then had to take a shower, put on the striped uniforms they gave us and go to be tattooed with a number. My uncle got A53 and I got A52. They put them on by using a needle, and I was bleeding. Later in my life, after the war, when I was being helped by some British people in London, they wanted me to go to a doctor to have my number removed. I refused, saying, “I’ve got this for life. This is how I was, and this is how I’m going to be. This is how I remember.”

At Blechhammer we had to walk five kilometres to our work every morning and then back again at night. The camp was very full, and we were among the last to arrive. Many prisoners were musicians who played different instruments, and their job was to play music for the soldiers and the SS. The musicians put on concerts, and we could hear them as we were led out to work.

My job was to look after the hut where the Jewish prisoners went when they had a short work break. I had to clean it and make the fires to warm it up for their return, but in the meantime I was able to roam around and see the other camps nearby. There was one where there were British soldiers, prisoners of war, and some of them would bring me extra food. They were very nice. One of the Jewish prisoners at our camp knew a German prisoner who also snuck us some food from time to time. The work for many of the men in our camp was to load pipes onto trucks. One time, I remember, I saw all the pipes fall off a truck, killing some of the prisoners.

There were bombings at night by the Americans and the Soviets. They bombed the factories, but they never touched the concentration camp. They must have known about us. At the factories, the prisoners built bunkers to hide in during the bombings, and one time when I had gone to look around, I saw an SS guy hiding in one. He told me to come inside to be safe from the bombs. I couldn’t believe he helped me like that. Another time I saw this same guy go over to a Wehrmacht soldier who had whacked a prisoner on the head with his gun, and the SS guy whacked the soldier and told him not to do that. As a result, this SS guy was later demoted to the Wehrmacht. I observed all this while I was wandering.

I didn’t work in the factory. I just went to look around because I was curious, and one day I was surprised by a man in a regular suit who asked me why I was there. I said I just wanted to see what work my fellow prisoners were doing. He was a Gestapo officer who told me to come with him, but there was another man there who was the highest authority over all the factories, and he told the Gestapo not to take me away, to leave me alone because he needed me. Then he sent me back to the hut. I was saved again.

What the Nazis did was horrible, but I could see, even then, that I couldn’t even think of being afraid. I had to do things that I knew I wouldn’t be able to do if I was scared. I knew I had to take care of myself.

The Last Camp

In February 1945, I was taken to Buchenwald, an enormous place. You can’t imagine how big it was. In one section, there were people from all nations — Poles, Germans, Ukrainians, Soviets — and in a separate area, all the Jews. Then there was a little part for the Roma. The Jewish section was full, so they put us into one end of the huge camp.

One day, I decided to go into the Jewish quarter to see what it was like, even though this was strictly not allowed. In fact, once you went in there, you couldn’t get out. But I didn’t even think about the risk, I just wanted to see it, so I went anyway, and when I walked through the door nobody said anything. There were four levels of bunks to sleep on, but the people there looked so awful. Suddenly I heard someone call my name, and when I looked around I saw one of my uncles, Lucia. He was half dead. He begged me to take him out of there. He could barely speak or walk. He was just lying there, dying. What could I do? How could I take him out? It was impossible. I didn’t know how I was going to get out myself. I hesitated, but I realized I couldn’t do anything for him. I had to leave him. That really bothered me so much, to see him like that and know there was nothing I could do. I just walked out the door and never went back there again. That Jewish section was so horrible. My section wasn’t exactly heaven, but that one was so much worse. We heard that groups of people there were regularly grabbed, taken out and killed.

I was in Buchenwald for a few months. The Germans knew the end was coming, and they were chasing people all the time and grabbing them. We were all running away from them, but they caught me. I had no escape, and they took me to the train with all the others they’d caught. Some were Jews, some were not. I was put in a cattle car with at least 120 other people. There were tons of cars like that and a lot of soldiers on the train with guns. We had no room to sleep. It was terrible. We kept going and going, we didn’t know where. Occasionally the train stopped and we could get off, but if anyone walked more than five feet from the tracks, they were shot.

We stopped once in a German town and I couldn’t believe my eyes. It was a big town that had produced crystal. I can’t remember the name of it, but everything had been bombed and completely wiped out. All that was left were big chimneys. The town was down to nothing. Another time, we saw an American plane flying over us with its machine guns lowered. Then they pulled up their guns and flew away. They must have realized we were prisoners from the camps.

Another time when we stopped, we were told to get out of the train one at a time and pull down our pants. I knew what they were looking for. They wanted to see if we were circumcised Jews. I didn’t want to go. I wasn’t going to lower my pants, so I dropped down under the train, in between the cars. I hid there, and when the inspection was finished, I climbed back up again. A lot of Jews were taken away. At another stop when we were allowed off, I saw a lot of grass all around, and I went and ate it. That was the only time I ate grass.

We were on that train, in those terrible conditions, for about four weeks. Finally, we stopped in Czechoslovakia. All the Germans fled and suddenly the Red Cross was on the train. They gave us food and took us to Theresienstadt. The camp had been liberated by the Soviets on May 8, 1945, and we were taken there to stay, not in the former concentration camp and ghetto, but in another building. There were quite a few men already there. They were the Jews who’d been forced to lower their pants when we’d been taken off the train earlier. I think I’d have been better off if I had let myself be taken then. I’d have avoided all the extra time on that horrible train.

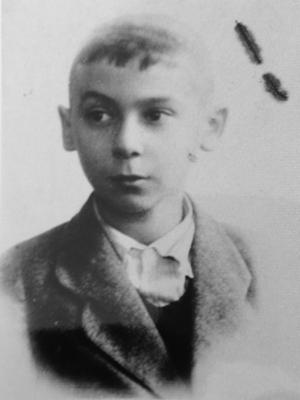

Simon's bar mitzvah. London, England, 1946.

Simon at around age fourteen. London, circa 1946.

Returning to Poland

In 2011, I did something I had vowed never to do as long as I lived. I returned to Poland. This experience had a huge impact on me and made me a different person. What made me do it? I had a feeling inside that I had to go back. My wife didn’t want me to go; it was definitely my idea. I wanted to see where I came from, and I wanted to go to Auschwitz. I went with a group of twenty-eight Jewish people, seven of whom were lawyers who were also judges. It was a private group, not a Jewish organization, and I was the only one who was a Holocaust survivor. They all treated me as a very special person.

During the trip, my wife and I had our own Polish guide with an assistant who took us to see all the old places — my town, my school, the areas where the Jews had lived. Our guide was fantastic. He wasn’t Jewish, but he knew everything, every place I wanted to see. I was able to speak to him and his assistant in Polish well enough to be understood, and they took me to my old towns of Będzin and Sosnowiec. I gave them my old address and we tried to go inside to see the rooms, but the current residents didn’t want to let us in. I did see the places I used to play, the Jewish cemetery across the street and also my grandparents’ and my cousin’s addresses. I was so pleased with the guides that I tried to give them money, but they didn’t want to take it. I finally pushed it into their pockets, and they thanked me.

So many memorials to the Jews have been built in the town of Będzin. This was such a surprise. I would never have believed the Poles would do such a thing or allow it to be done. There is a large stone monument with writing carved in Polish to mark where the synagogue once stood. There is also a part of a train set up behind another memorial stone marking the ghetto in Będzin.

Our guide told me he had a surprise for me and took me to a little place for which he had a key. It was a small synagogue for ultra-Orthodox Jews and it was still intact, its walls still decorated with gorgeous paintings. I never knew about it even though it was very close to where I had lived. I was so shocked that it had not been destroyed by the Germans.

I also went to Birkenau, where I said Kaddish for my mother. In Auschwitz and Birkenau, I was surprised to see so many paintings and photos of what the SS and the Gestapo had done to us, and I learned that, at the time, most Polish children had to go to visit the concentration camps and the ghettos as part of their public school program.

The people I met in Poland couldn’t do enough for me. They were so friendly and helpful, especially the young people, students from the university. I couldn’t believe how much had changed and how different my experience was with the Polish people I met there on my return. I am very happy that I went back. I would never have believed there could be such a change. I had such hateful memories, but it’s a different country now from the one I remembered.

When I got back from Poland, after visiting my town and experiencing how different the people are now, I decided I had to start talking about my experiences because I owed it to all those people who had died. That’s when I went to the United Jewish Appeal Federation in Toronto and, through them, began to talk to school kids — mostly Catholic kids — about the Holocaust.

I had said I would never in my life go back to Poland because of all the horrible things Poles had done to me and to the Jews when I was a kid. As a result of these terrible memories, I had never wanted to tell anyone about the Holocaust. That was how I was until I finally did go back. Then, as I’ve said, I became a different person. I decided I wanted to write my memoir. I felt I had to tell people how we suffered, not just for those who died but for those who lived, those who went through so much. We will never forget what we saw. It will always be a part of us, as long as we live.

Simon in front of the memorial that commemorates the Jews deported from the Będzin ghetto. Będzin, Poland, 2011.

Simon Saks with his Sustaining Memories writing partner, Sandi Cracower. Toronto, 2015.