Renee Singer

Born: Brussels, Belgium, 1933

Wartime experience: Hiding, passing/false identity

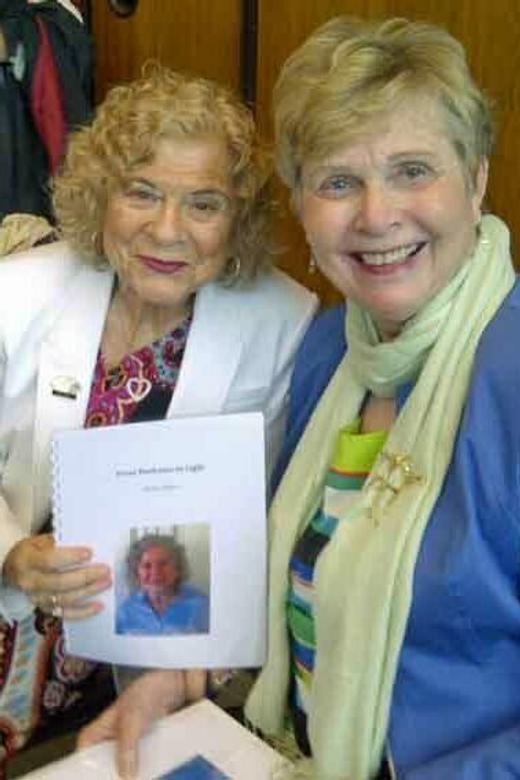

Writing partner: Dianne Moore

Renee Singer (née Cymerman) was born in Brussels, Belgium in 1933. When Nazi Germany occupied Belgium in 1940, Renee and her family fled to France, where they were captured by the collaborating French government and imprisoned in a transit and internment camp.

They were smuggled out of the camp and returned to Brussels, where Renee’s father was taken by the Nazis, and the rest of the family went into hiding. Renee’s mother then sent her to a Catholic monastery. After the war, Renee, who had been orphaned, remained in the monastery for a year and was then sent to a Jewish orphanage in France. In 1947, Renee was on the ship Exodus, which attempted to sail to Palestine but was turned away by the British. Renee spent about a year in a displaced persons (DP) camp in Germany and then immigrated to Israel in 1948. She married and had three children and later moved to Canada, settling in Toronto.

When Everything Changed

I was born in Belgium in March of 1933. My mom’s name was Fanny Lajtman, and my dad’s name was Ely Cymerman. My dad was a manager at the Côte d’Or chocolate factory. We lived in Brussels, and before the war, we had a good life. We lived in a two-storey attached house on rue Eloy 29, and our house was always full of family and friends. My mom was an excellent seamstress. She did embroidery and made men’s shirts, as well as pillowcases and duvet covers. She also did manicures. My grandmother lived with us and did the cooking and took care of me. I was very attached to my grandma. I called my mother Maman, and I called my grandmother Mama.

In 1940, everything changed. The German army was advancing toward Belgium, and our family decided to leave Brussels to join my aunt’s family in Paris. Nobody believed that France would fall into the hands of the Germans, and my family thought that we would be secure in France. We could already hear bombing when we left and boarded a train destined for Paris. Along the way the train was bombarded and the railroads to Paris were destroyed. Our train was forced to reroute to the south of France. After six days on the train, we finally arrived in Fronton, a small town near Toulouse in southwestern France. We rented a room in a family’s house, and I attended school, starting Grade 1. At that time, my mom was in the late stages of pregnancy, and shortly after we arrived, my brother, Albert, was born in Toulouse on Bastille Day, July 14, 1940. I don’t remember where my dad was during our time in Fronton — maybe he was away looking for work. I don’t have a lot of memories of my dad, and I only remember him vaguely.

We’d been in Fronton for several months when the Vichy government, which collaborated with the Nazi regime, started to round up Jewish people in the area. We were taken along with other Jews to a deserted castle that had no windows or doors and looked very neglected. Early the following morning, trucks arrived to take us to a transit or internment camp. Conditions there were horrendous. We were barely fed. I can still remember the horrible soup we were given. We slept on stretchers that were placed on the floor, and we were hungry, cold and afraid. My family decided that we had to escape and paid a smuggler, in money and diamonds, to get us out of the camp. At first he didn’t want to take us because it was too risky with a baby, but I guess he eventually agreed because we offered to pay him extra. The smuggler had a big truck, and we travelled by night and hid in barns during the day. It was a cold and rainy winter, and I remember the mud. After a while we reached the Swiss border. We tried to enter Switzerland, but the border guards refused to let us in, so we had no choice but to go back to Brussels.

Belgium was already under German occupation. We went back to our old house, and I went back to school. One morning not long after we had returned, the principal of the school entered my classroom and announced that from then on, all the Jewish students could not attend school anymore. After that, I stayed home with my brother and grandma. I was very sad. To somewhat normalize our life, my mom and my grandmother took us to the park or to Boulevard de la Révision to play and meet other Jewish kids who could not attend school. From May 1942, all the Jewish people and children from the age of six were forced to wear a yellow star. From that point on, we seldom left the house.

I have one horrible recurring memory of an event that took place then. Times were very tense, and my mom hesitated to let me out of the house. I loved ice cream and longed for it very much. I begged my mom to let me and my little brother go and buy an ice cream at the parlour that was over in Boulevard de la Révision. As we were approaching the Boulevard, I saw SS soldiers rounding up Jewish people into a truck. The Nazis often directed surprise raids and mass arrests of Jews who were walking in the streets. One of the German SS soldiers approached me and asked if I was Jewish and where I lived. I answered “no” and pointed in the opposite direction to our house. The soldier let us go. A friend of the family had been looking out her window at the time and saw the soldier talking to me. She concluded that my brother and I had been taken with the rest of the Jews who were on the street at the time. When my mother heard the news, she fainted. It was a tragic event in my house. In the meantime, scared but determined, I took my little brother on a very long detour to come back home (of course, I didn’t get any ice cream). To my family’s great surprise, we arrived home a few hours later. I remember my mom crying, laughing and hugging us as if a miracle had just happened to her. My family celebrated our return with a bottle of wine and the house was full of joy.

I can still remember hearing the SS soldiers’ boots when they came down the street to round up Jewish people from their homes.

Becoming a Devout Catholic

We had wonderful gentile friends who lived in rue Eloy 21. Their two children were my age, and we were good friends. Every evening, before the 8:00 p.m. curfew, they would let us hide in one of their bedrooms and stay for the night. They even arranged for my little brother to sleep on a special bed under their beds. My grandma refused to leave our house and insisted on remaining in her room.

I can still remember hearing the SS soldiers’ boots when they came down the street to round up Jewish people from their homes. They were very loud and scary. On one of these nights, my father was trying to hide on the roof. The SS soldiers spotted him and chased him. I never saw my dad again.

My grandmother hid in the upper storey of our house, and we hid at our neighbours’ place. My baby brother was silent and didn’t cry when the SS soldiers entered the house where we were hiding. After the Germans left, we went back to our house to check on my grandmother. The door of the house was sealed — meaning that all the occupants of the house had been taken. My mother was devastated. She quickly ran to the upper floor and, to her amazement, found my grandmother still there, hiding quietly. We were all so happy to know that she was still with us!

As things got harder and more dangerous, my mother decided to hide my brother and me together somewhere where we would be safe. When she found out that monasteries would take only girls, she arranged for me to be hidden in a Catholic monastery. One day my mom told me that I would be gone for a month or two until the war was over, hiding in a monastery. She encouraged me by telling me that I would be going to school there and would have lots of new friends. She also told me that I needed to choose a new name that didn’t sound Jewish. I chose the name Francine Vermeulen, using the first name of one of my friends and the last name of another friend.

One morning, Mom took me to the train station where a gentile woman was waiting for us. As soon as we were on the train, the woman said that I needed to assume my new identity and never ever mention to anyone that I was Jewish. The Saint Vincent de Paul Monastery was by the French border near Mons. There were fifty-five girls living at the monastery, twelve of whom were Jewish. We couldn’t say who the Jewish girls were, but in our hearts we all knew. I had a very hard time getting used to life in the monastery. At the beginning, I didn’t always turn around when I heard the name Francine called out because I wasn’t used to it. But as time passed, I got used to my new name and my old identity started to fade away.

Initially I received some letters and small packages from my family. But soon I stopped hearing from them. I lived in the monastery and became a devout Catholic. I was baptized and learned the Catechism of the Catholic Church. My godmother was the niece of the head nun, and on holidays I used to go and stay in her home. During the time at the monastery, my ambition was to become a missionary and go to the French Congo.

After the war ended, the Jewish girls in the monastery were picked up by their surviving family members. Soon, I was the only Jewish girl left who hadn’t been picked up. One day, the nun informed me that no one from my family had survived. I was devastated and felt totally alone in the world. I didn’t want to leave the monastery. I loved the nuns and felt that they were the only family I had.

One year after the war was over, I was collected from the monastery by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee or the “Joint” as it was called. The Joint sent me to an orphanage that they had set up in an old chateau in Les Andelys, France. There I was helped to gain back my Jewish identity and overcome my loneliness. I went to school with many other children from the village. I have very fond memories of my time in Les Andelys.

Many years after the war, I found out that my brother had also survived. My mother had saved his life by hiding him with a gentile family in the suburbs of Brussels. My brother still lives in Brussels and has one son.

Renee Singer. Place and date unknown.

Renee, left, with her Sustaining Memories writing partner, Dianne Moore. Toronto, 2015.