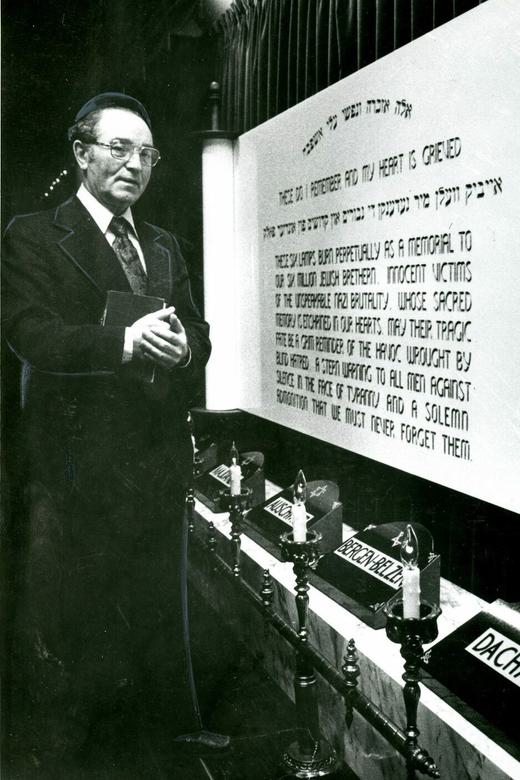

Rabbi Peretz Weizman

Born: Lodz, Poland, 1920

Wartime experience: Ghettos and camps

Writing partner: Erin Gano

Peretz Weizman was born in Lodz, Poland, in 1920. He was raised in a Chasidic home and his family were followers of the Gerer Rebbe.

After the onset of World War II and the occupation of Poland in 1939, Peretz and some of his family briefly fled Lodz but soon returned and were forced into the ghetto. In 1942, Peretz evaded a mass deportation, but he and his remaining family members were captured and tortured by the Kripo, the Nazi criminal police. In 1944, Peretz was deported to a forced labour camp at the HASAG ammunition factory in Częstochowa. After the camp was liberated by the Soviet army in January 1945, Peretz made his way back to Lodz. His parents and five siblings were all killed in the Holocaust. In Lodz, Peretz met his wife, Ryvka (Riva). They married in 1946 and later moved to Israel and then to Winnipeg in 1953 with their two children. In Winnipeg, Peretz served as a congregational rabbi for over fifty years. Rabbi Peretz Weizman passed away in 2020.

Days of Cruelty

World War II broke out on September 1, 1939. A deadly fear befell the Jewish people. A week later, the Germans conquered Lodz. Thousands of people fled from Lodz to Warsaw. Lodz was closer to the German border than Warsaw, the capital of Poland. Common sense dictated that the further you were from Germany, the safer you were. In Warsaw, the Polish army would reorganize and establish a powerful offensive against the Germans — or so people said.

I was standing on our balcony at about four o’clock in the morning when I saw throngs of people running in the direction of Warsaw. My father told us not to leave Lodz. In retrospect, he was right. Most of those who ran away came back. Also, the Germans spotted the fleeing people from their airplanes and shot at them. Hundreds were killed. This was the first attack on civilians. Those who remained in their homes were the lucky ones.

The Germans occupied Lodz just days before Rosh Hashanah and decreed that all stores be open on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur and that all synagogues be closed. It was the first of the black High Holidays. Heavy dark clouds hovered over the Jewish people. Looting, beating, maiming and killing were the order of the day. Anti-Jewish decrees piled up. Curfews, restrictions, degradation and humiliation were our lot.

On the High Holidays, people gathered in attics, cellars and in hiding places to conduct the services. The situation was unbearable. Leaving home was dangerous. As soon as the Nazis, with the help of the Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans) recognized a Jew, they would drag him to work where he would be beaten to death. The Nazis raided Jewish homes, restaurants and businesses, and dragged people away, never to be seen again. Jews riding on streetcars or buses took their lives in their hands, as many Jewish passengers were thrown out of moving vehicles and were maimed or killed.

There was no let up. Each day was worse than the one before. Disorientation and confusion mixed with hopelessness and helplessness was the state of our minds. We felt deceived; we felt disillusioned. We felt hunted; we felt choked and squeezed. The wise had no advice, the rich had no power, the scholars no influence, the prominent did not command respect, the pious no reverence, and the mighty had no strength. Life became hollow, empty and cruel. The Germans robbed us of everything we had and everything we believed in.

On Yom Kippur, as the Germans had ordered, our business was open. Two Germans came in and looked around, making up their minds about what to loot. They pointed to a few ten-kilogram containers of glycerine. When my father lifted one of the cans to hand it to the German, to our bewilderment, he refused to take it. He said to my father, “Not you. You are an older man, older than I am. You should not strain yourself.” Pointing to me, he said, “Let him carry. He is young and has strength.” What a gentleman, a vicious animal with manners, stealing and looting in a German Übermensch way.

The Germans did not see any contradiction in such behaviour. Their entire psychology was distorted and perverted. This was the mortal enemy that we so boldly faced. Logic and common sense did not exist. Hitler and Nazism had extinguished and eradicated them, and only blind animalistic hatred reigned.

Trouble followed trouble. Every day brought new restrictions, deprivations and degradations. To break our spirits and to spread fear and anxiety, the Germans hanged people in public places and in markets. In certain parts of the city, some Jewish families were transported to Lublin, creating chaos in our minds. Nobody knew where he or she would end up in the next hour or day. All of us were alert and ready to be sent away to places unknown to us.

All this was perpetrated in Europe, out in the open and within view of society. The world did not react at all: silence and indifference were humanity’s reaction. We Jews were abandoned. Before being annihilated by the Nazis, we were written off by the world.

Mr. Wojciech, a Polish man who had worked for us for many years and had carried me to cheder in the winter when I was a child and had seen how we celebrated our Saturdays and Jewish holidays and our family’s simchas (happy occasions) and knew our glorious life, saw what the Germans were doing to us and said to my mother, “Lady Weizman, I doubt if there is a god.”

***

In November 1939, I saw the Altshtot Shul (Stara Synagogue) go up in flames. The Germans burned down this magnificent edifice, the pride of our community. The building, with its holy contents, was engulfed in flames and consumed by fire. Gazing through my window, I saw the entire sky over Jewish Lodz covered with sparks. Everything was destroyed. I am one of the sparks that survived. Only the heavy walls remained as a testimony to our glorious past, as a monument to our terrible present and as a warning of our doomed future. Looking at this skeleton, we realized how vulnerable and helpless we were. We had become fatherless.

***

In the Lodz ghetto, where starvation and fear of death were pervasive, there was a small shul located at Brzezińska 23 that had gone unnoticed by the Germans. In this little place of worship, there was a lectern at which the chief rabbi of Lodz, Rabbi Eliyahu Chaim Maizel, studied and prayed. Every Sabbath, a small group of people worshipped in this shul. It is impossible to describe the depressive, cold atmosphere that prevailed in this place.

At this shul, I met the great cantor of the Altshtot Shul. With my tearful and desperate eyes, I compared him to what he had been before. He was no longer tall. He had become shorter and thinner. He was wrapped in sorrow and grief. I approached this great, heartbroken cantor and said, “I would like to sing for you a cantorial piece of the Sabbath prayer that you sang at your synagogue. Please allow me to chant it for you and tell me if I sing the way you did.” The cantor listened most attentively, and tears welled in his eyes. With a choked voice he said, “You sing it exactly the way I used to chant it.” I felt as though I had recreated his glorious past and injected in him a great sense of hope and comfort. I never saw him again.

I am known as a walker. Every day, I walk about two and a half miles. My route is Main Street. The storekeepers know me, and they watch me and wonder how an old man like me (thank God in shape) walks so briskly. While I walk, I am always humming. I was once asked, “Tell me, what melody do you sing?” I did not reply. But now, I will reveal the secret: I sing and chant the Sabbath renditions of the cantor of the Altshtot Shul of my home city, Lodz. The beautiful synagogue is completely erased, not a remnant left. The glory of this period is gone forever. The cantor and his choir were murdered. The people who worshipped were tortured and killed.

My outcry is: What can I save?! What can I rescue?! What can I preserve and keep alive as a reminder of such a glorious epoch of Lodz Jewry? I saved and rescued the precious melody of this cantor and synagogue. The melody survived. The Germans could not destroy this melody, and it escorts me always. I will hold on tenaciously to it. I will never part with it. It is all that is left. That is why I say that I never walk alone. I walk with this immortal, heavenly melody that I rescued from the hellish fire. This melody gives me life after six million deaths.

Gazing through my window, I saw the entire sky over Jewish Lodz covered with sparks. Everything was destroyed. I am one of the sparks that survived.

Valley of Tears

In 1942, a few days before Rosh Hashanah, after two years of starvation, desperation, degradation, epidemics and deadly fear, the Germans ordered children up to age ten and adults aged sixty-five and over to be evacuated from the ghetto, without revealing where they were going.

Hopelessness descended upon all of us. The ghetto became a valley of tears, a deeper and darker place. All the previous illusionary, optimistic explanations for why so many Jews were sent away from the ghetto to work for the German war industry were defied. The truth was obvious. Children were not to be enrolled in work, and they were not going to be placed in kindergartens. They were going to be destroyed. We all realized that we faced death, that the more than 200,000 Jews in the Lodz ghetto were condemned to perish.

It was Friday; Sabbath candles were lit, visible from the Jewish windows. But the Sabbath candlelight could not dispel the sadness and helplessness that permeated the ghetto. Instead, the Sabbath candles deepened our darkness and magnified our calamity. The candlelight seemed to illuminate the destruction that was in store for us. Everyone ran to hide, but where was there to hide? Only a grave.

My sister Yito had two little kids, Shlamek and Simek, ages six and four, and I felt I had to do everything possible (and even impossible) to help her save her children. Suddenly, I noticed Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski, the Jewish head of the ghetto, passing by our street. My father knew Rumkowski personally from before the war. He used to visit our home to collect money for the orphanage that he was in charge of. I ran to my mother, asking her to approach Rumkowski and plead with him to save at least one child. My mother remained silent for a minute, then she looked at me and said, “Which one?” Even now, when I reminisce upon this painful incident, I am full of shame and embarrassment. How could I come up with such a cruel idea? I was so immature, so stupid and so desperate.

***

During the roundup of children, the ill and the elderly, an action known as the “Sperre,” thousands were killed, but we were saved. This is how. The order was that the Jewish administration would provide the Germans with everyone under ten and over sixty-five years of age. On that Friday, Rumkowski called the people of the ghetto to assemble at Lutomierska 13 so he could address them. In his address, he asked people to make sacrifices.

It was obvious that to be taken away meant to be killed. The next day, we were told that the Sperre, the mass deportation, would start at five o’clock. Nobody would be permitted to leave their homes. Those who did not follow the order would be shot. We became prisoners in our homes. We had to remain without the already scarce food and drink for an unknown number of days.

The Jewish police, furnished with a list, started by going from building to building to round up the victims. But they met with resistance from some parents, who were armed with knives and iron cleavers. There were rumours in the ghetto that Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski told the Gestapo that the administration could not implement their request. The Jewish police got a guarantee from the Germans that by implementing their order, their children would be saved. The Germans would join the Jewish policemen to do the job.

The only way to save the children and the elderly was to hide them. But where? I took my sister Yito’s two kids to look for a hiding place. I was running from place to place together with many others, but to no avail. No place was safe. We were running, but time was running even faster. It was already five minutes to five. At five, we weren’t permitted to be seen outside. We could be shot. Oh God, what could we do?

The difference between life and death happened in a split second and with a little luck. My brother Mordechai found a place to hide our loved ones. Mordechai was always outside, monitoring the situation, and he risked his life for us. We took the kids and the women and hid them in a cellar that belonged to my father. There was a little hole to the cellar that provided them with light and fresh air. The men were left in a room above ground, and Mordechai put a big lock outside the door, to give the appearance that no one was there. Mordechai himself remained outside, or perhaps hid in an attic.

The process of rounding up the people was as follows: Germans and a few Jewish policemen would raid a building, shooting a few times in the air and yelling for everybody come down. Then, the people they had selected were placed on a wagon to be taken on closed trucks to Chelmno — to be gassed and burned. I looked through the window from our locked room and I saw people being chased to the wagons. As soon as a certain section of the ghetto was combed, the police guarded it to make sure that people from the uncombed section would not try to hide there.

We brought our family up from the hiding place on Erev Rosh Hashanah. I think that the Talmud says that Joseph was drawn up from the pit on Rosh Hashanah. I am sure that the Germans did not know about that. Those who had been in the cellar were tired and weak and had difficulties seeing because they had been in darkness for quite a few days.

In spite of all the painful troubles, we prepared ourselves for Yom Tov. Mordechai was on watch. He came home telling us that the Germans were going to raid the ghetto again. There was no time left to hide in the cellar. We remained in our rooms, and Mordechai put a lock on the door again. Again, he risked his life to save us. This was the kind of person Mordechai was and this is how I remember him. He will continue to live in my heart and in my mind.

Light in Darkness

On March 4, 1944, officers surrounded the Kripo police station and chased us into cattle cars. The train was moving, but we didn’t know where they were taking us. At around four o’clock, we arrived at a place unknown to us. We were surrounded by Lithuanians and Ukrainians with rifles ready to be used. They took us to a bath and then brought us back to barracks that were located at an ammunition factory. The factory was run by HASAG, and we were in Częstochowa. They allowed us to send postcards to our families to let them know where we were, but of course, our families never received the mail.

Within two days, we learned how to operate the machines, which were quite complicated. Eventually, I became an expert in producing the very bullets that could have been used to kill me. There were seven machines under my supervision. If we did not produce the quota, we were severely punished.

One of the Germans in charge of the production, Darring, was a sadist who enjoyed torturing people, especially Jews. Looking at him was like seeing the angel of death. At the sight of him, some of the inmates would become paralyzed with fear. Somehow, I was fortunate enough not to draw his attention. I kept myself very busy and smeared my face and hands with grease to give the impression that I was a productive slave. It seemed that this trick worked and protected me.

The conditions in the labour camp were much better than in the ghetto. We received more food. Polish people were also employed in this factory, although they were not treated as slaves but as workers. They got paid and were free to leave after work hours, returning to their homes. At lunch time they got soup just as we Jews got soup, but their soup was of a better quality.

There was a non-Jewish girl who worked next to the machines that I operated who gave me her portion of soup. A Polish boy, perhaps her boyfriend, noticed her generosity and reported her. Almost immediately, there were announcements in Polish throughout the factory, “If you cannot eat the soup pour it out, but don’t give it to a Jew.” If this incident had happened a few months earlier, I would have been shot immediately. Luckily, it happened at the end of November 1944, not long before the liberation, when every pair of productive hands was needed by the Germans.

***

Throughout the Holocaust I did not miss a day of putting on tefillin, except for the three weeks I was incarcerated in the Kripo station. Unbelievably, even in the labour camp, we organized a group of eight or nine people, and we put on our tefillin every day before we went out to work. Somehow, one of the men in our group had smuggled in a pair of tefillin, endangering his life.

In one of the most hidden corners, we gathered every morning to share the tefillin. One morning, a Jewish kapo (foreman) by the name of Yidl Frankel noticed that we were putting on tefillin, and he became hysterical. He yelled at us, calling us the most embarrassing names, screaming with all his strength, “You … Chasidim, take off your tefillin immediately, or I will kill all of you!”

I had a good relationship with the kapos, and I approached him calmly, saying, “Yidl, why are you so furious? Why are you yelling? What do you have against the tefillin, and what is wrong if we are putting on tefillin for one minute?” He responded with all the strength that he could muster: “You see, you … Chasidim … in Częstochowa there are about six or seven thousand Jews alive. All of the Jewish people in Poland were murdered. Do you know why we are alive? I will tell you, you Chasid. We are alive because God forgot us. Praying to Him, you will remind Him that there are still some Jews alive, and the result will be that all of us will be murdered.” We were dumbfounded and asked God to give Yidl the answer if there was an answer. We continued with our daily practice of the tefillin, and Yidl turned a blind eye.

***

One way to escape the brutal reality of the hell we endured during the Holocaust was to go back in time and imagine that we were living in the past before the war. The dates of the Jewish holidays helped us to forget the present and to live, even for a moment, in days gone by. We tenaciously held onto days of celebrations and pretended to find ourselves in the festive seasons.

In 1944, sometime in December, I made up my mind to observe the festival of Chanukah. With some help, I was able to get a few pieces of paraffin wax to make Chanukah candles. Before we were assembled to go to our slave work in the munitions factory, I lit a few candles and placed them on the bunks where we slept.

While I was working, I realized that leaving burning candles in the barracks might have put me in grave danger. The Germans would think that I was planning to burn down the entire camp. This would be seen as the worst form of sabotage, and I would be shot immediately. I decided that, somehow, I had to do whatever I could to get back to the barracks and extinguish the candles. This was easier said than done.

I snuck out of the factory and back into the barracks. Every step was risky, as every place was watched by the SS and Ukrainian police. I was lucky I made it, and I put out the candles. As I was re-entering the factory, a policeman caught me. I gave him some excuse, but to no avail. His verdict was that I was to get fifty lashes, but for whatever reason, the SS turned a blind eye and I stepped aside. I mingled with a group of Jews who had arrived for the second shift and vanished. This Chanukah was full of new miracles.

When I look back, I ask myself why I endangered my life to fulfill the mitzvah of Chanukah. It was because I believed that the fulfillment of the observance would protect me. My conviction was that the joy of Chanukah that I experienced in my childhood still lingered in me and that no power in the world could extinguish its light. I truly believed that the Chanukah light would expel all the darkness and evil that dominated.