Philip Tabachnick

Born: Będzin, Poland, 1931

Wartime experience: Escape, Soviet Union

Writing partner: Annabelle Sabloff

Philip (né Pinchas Isaac) Tabachnick was born in Będzin, Poland, in 1931. Philip, the eldest of three brothers, was travelling with his family outside their hometown when World War II started, and he fled with his family to the Soviet-occupied area of Poland.

They stayed in the Soviet Union for the duration of the war, enduring hardships for about a year in Kursk, then travelling to Voronezh and Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan. After being in Tashkent for a few months, the Soviet authorities sent them to Leninabad (now Khujand), Tajikistan, as labourers. Philip and his family returned to Poland briefly after the war, in 1946, and then left Poland for Austria, where they lived in a displaced persons camp for two years. Philip and his family immigrated to Canada in the spring of 1948 and settled in Toronto, where Philip worked in the garment industry. In the early 1950s, Philip met and married Joyce and together they raised a family. Philip Tabachnick lives in Toronto.

Growing Up in Poland

I grew up in a nice apartment in Będzin, Poland, which my family rented from kind Polish gentiles. We didn’t have indoor plumbing, but we had a white-tiled stove. Every Shabbat, a gentile came to light the stove for us because Shabbat restricted us from doing this task. Our extended family lived within walking distance of one another. My grandpa lived just a few buildings away, as did an aunt and my maternal grandmother. Our extended family all spent time together; we celebrated all the Yom Tovim, the holidays. I remember Passovers with everybody all dressed in white, with the table by the bed and everyone reclining on pillows. I used to love the chicken soup with lokshen, noodles, and the bobes, large beans that I’m not sure the name of in English, maybe broad beans.

There were several sewing machines in our apartment because my father, a tailor like his father, had four or five people working for him. He produced men’s and women’s clothing. Since we lived not too far from the German border and my father could speak German (and we kids also picked it up), he would go to the German side to sell his goods. He didn’t make a lot of money, but he made a nice living. My mother was talented and would help wherever she could, sometimes assisting my dad with sewing. She was a mother, a wife and a housekeeper, and she was more laid-back than my father.

I started school in 1938, when I was seven years old. I remember going to cheder, a religious elementary school, where I had to wear a kippah. When I got home, I played with my schoolmates in the house and ran around outside, so we took off our kippahs, and there was always the odd kid threatening to tell the rabbi that you took off your kippah.

Although Jews interacted mostly with other Jews, family and acquaintances, we got along fairly decently with the gentiles. But I do remember the antisemitism. I could see it and feel it in people’s looks and their attitude, the things they said and the way they said them. Even when I was young, I could pick up on it. I remember when I was seven years old and in Grade 1, just before the war started. To get to the school I used to have to walk across a bridge, and there were trains under the bridge. One day a train came along as I was crossing, and I stood there and watched the train, with the smoke billowing around me. And when I got to school a couple of minutes late, the teacher, a Polish woman — I’ll never forget what happened as long as I live — she gave me what for: she took a wooden container that had pens and pencils inside and made me hold out the palm of my hand and then she whacked me, maybe three or four times. I saw white stars. I realized, even at that time, how antisemitic she was! How could anyone do this to a seven-year-old?

The antisemitism was often horrendous, but I remember, as a child, hearing stories about Jews standing up for themselves. Just before World War II, for example, the Jews in my city got wind of a plan being hatched for a pogrom. They heard that Poles were going to come in from the farms and the surrounding areas with their horses and buggies, and they were going to beat up Jews. We had a river running through the city, and there was a bridge crossing the river. These gentiles, farmers mostly, started to cross the bridge with their horses and buggies, and who knows exactly what they were going to do to the Jews. But there were a number of tough Jewish men in our city — they had no other choice but to be tough. The circumstances made them what they were, since living with antisemitism meant not being allowed to go to certain schools or not having the means to attend. Being tough was forced on them, and they didn’t take any abuse if they could help it. Sometimes they would even go out of their way to catch a Pole alone and beat him up, to teach him a lesson. When the Poles crossed the river, they were met by these tough guys who threw them, their horses and their buggies flying into the river!

Philip (right) with his parents and baby brother Morris. Będzin, Poland, 1933.

Philip (front row, second from the right) with his two brothers, Morris and Solomon (Saul), and a cousin (far right). In back, left to right: Philip’s parents, Louis and Helen, and Philip’s uncle. Philip and one of his brothers have shaved heads due to recovering from malaria. Będzin, 1930s.

Fleeing War

In the summer of 1939, we were travelling in the Polish countryside and were in a town called Otwock, not far from Warsaw. The place was filled with trees and sand and cottages, and mostly Jews vacationed there. My parents, my two brothers and I were there along with my mother’s brother Shmiel, who was married to my father’s sister Chasura, and their four children and my mother’s sister, her husband and their four children, as well as my maternal grandmother. It was a beautiful area.

On September 1, 1939, the war broke out. I was not quite eight years old and up to that time, I hadn’t heard any rumours of war whatsoever. I still remember distinctly that it was a grey, overcast day with a very fine drizzle almost like a mist. We heard explosions that sounded like they were coming nearer. Everything shook, even the dishes in the china cabinet in the dining room. The rumours were that these were military manoeuvres, but as the day wore on, we found out that these were not military manoeuvres: Germany had attacked Poland, and it was a war. We could see artillery fire back and forth on the horizon, and we knew the war was on.

Two or three days later the Germans came in, the actual troops; we watched them walk in. When they bombed the area, we knew, instinctually, that we had to hit the floor. While lying on the floor near a huge picture window, I saw a piece of shrapnel come through the window and get stuck in the wall. I touched it and got a blister, a burn, right on my finger. I didn’t expect it to be red-hot! It was frightening.

Soon, we began hearing all kinds of rumours that the Germans would take away the men and leave the women and children alone, so my dad and his two brothers-in-law, along with other men, took off. They returned a few days later, realizing they had left the women and children alone and unprotected. They came back to get us.

We never did go back home to Będzin. A short while after the war started, we left from Otwock by horse and buggy, heading east. Everybody piled into the buggy — my cousins, parents, uncles and aunts — and we went across Poland to Białystok. We slept in farmers’ stables with pigs and cows, which was terrible. I slept near a farmer who snored louder than twelve pigs put together.

As we were travelling toward the Soviet-occupied side (by then, Poland had been divided between Germany and the Soviet Union), we saw two German soldiers on the horizon; they looked small. Then, we heard two shots flying by us. My parents yelled, “They’re shooting at us!” We put up our hands. One of them came running, and he was so upset he almost crossed himself, shouting, “I could have killed you!” My parents spoke German and they said we were Volksdeutsche, meaning we were of German descent, and we were going across the border to visit family. My dad handed him cigarettes as they spoke, and we finally got across. This must have been a very difficult situation for my parents.

We then crossed over to the Soviet side of Poland and got to Lvov (now Lviv, Ukraine). I don’t remember how long it had taken us to get there, maybe days or weeks; it was probably October or so when we arrived, and it was very, very cold. My uncle and aunt, my mother’s sister Shaindel, got an apartment but didn’t have room for us, so we wound up sleeping in a Catholic church. It was the coldest winter I can remember in my entire life, and there was no heat in the church. We burnt coal in metal pails to keep warm.

From Lvov we went through Kiev (now Kyiv) by train and wound up in a city called Kursk, in the Soviet Union. I think we arrived there in 1940. My dad got a job working as a tailor in a factory and eventually became the manager.

I went to school in Kursk. I was a very good student and picked up Russian quickly, since I am good at languages. We were well treated. I joined the Young Pioneers, a Communist youth organization, and as part of the uniform we all wore a red neck scarf. A lot of the program included praising the country, Stalin and the Communist system.

Our parents warned us never to say anything that might seem to be against the government, either at school or elsewhere. During Stalin’s regime, everybody was being spied on. When friends sat around at our place and started talking about the regime, my mother would go over to the front door and open it suddenly. Sometimes, somebody would jump away — they’d been listening in. It was a really horrible way to live.

I can only remember going up in the air from the force of the explosion but not coming down. The next thing I do remember, I was on my hands and knees, shaking my head, seeing smoke coming from the building. I had a lot of close calls like these.

War Returns

On June 22, 1941, Germany attacked the Soviet Union. Planes were bombing and strafing, and anti-aircraft guns shot at them, exploding everywhere but not hitting anything. I was nine years old. While I was standing against a wall of the building where I lived, a bomb suddenly fell across the street, near a police station, I think. I can only remember going up in the air from the force of the explosion but not coming down. The next thing I do remember, I was on my hands and knees, shaking my head, seeing smoke coming from the building. I had a lot of close calls like these.

When the German attack began on the Soviet Union, we fled again. The fighting was getting nearer to where we were, and some of the Jews, including my mother and my brothers and me, took off to go further east. Under Stalin’s Communist regime, my father couldn’t leave his job. From Kursk, my mother, my brothers and I and a couple of other friends went northeast by train to Voronezh. We were on our way to Central Asia. It was a night trip, and as planes flew over, we heard strafing. Somehow, we got to Voronezh safely. When we got off the train, we encountered wall-to-wall people from all over; some were Russians, some Jewish. We had to walk over people. We kept hearing rumours of what was being done to the Jews. There was no family for us to go to, and nowhere else to go. Our only choice had been to go east. From Voronezh, we wound up going to Uzbekistan, a country north of Afghanistan that was then part of the Soviet Union.

As we travelled east, the train stopped just at the foothills of the Ural Mountains. I knew where I was because I had always been curious and used to read whatever I could get my hands on, especially geography. I knew that the Ural Mountains represented the dividing line between Europe and Asia. Looking out the window of the train, I didn’t think the mountains looked that steep, and I wanted to explore. The man in charge of the train warned me not to go too far because we were just stopping to get some water for the locomotive, and if I went too far, he would have to leave me there. He said he’d beep twice, and then I was to run back to the train. I started to climb, and the terrain was smooth, not rocky, but it became quite steep before the top. I heard two beeps and started to run back, but I couldn’t make it, and the train was already moving. I remember some men coming down and grabbing me, just throwing me into the car, and I felt like, Thank God. My mother was fit to be tied.

We went through southern Kazakhstan, which was amazing: I saw camels and steppes, just wild country, and the people there wanted my shirt, so it got traded for a little bag of rice, for which I was happy.

We arrived in Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan, with the same feeling of not having a place to go. We slept by the railway station. There were other Jewish people with us, but no one related to us.

We spent a few months in Tashkent, living with gentiles here and there. At some point in 1942, the Soviet government sent us to Leninabad (now Khujand), a city in Tajikistan, another Soviet Socialist Republic, north of Afghanistan, because they needed labourers to work in the cotton fields.

We went through some very rough times in Tajikistan. We lived on a kolkhoz, a collective farm, where everything was owned by the government. Our work was hard, and even us kids had to work. We had to pick cotton, and when the cotton was all picked, however many days or weeks it took, we had to pull out the plants by the roots. Our hands got blistered. At the end of the day, we were given 400 grams of black bread to eat, which was the texture of putty. All we had with that was a cup of boiled water. It was horrible.

I remember the hunger clearly and distinctly. My parents — we had now reunited with my father — used to walk to towns fifteen or twenty kilometres away from the kolkhoz and come back with whatever food they had found. We kids would ask them, “Aren’t you going to eat?” “No,” they would answer, “Mir hobn shoin gegessen” (we have already eaten). Now, of course, I realize they hadn’t.

When we could steal some corn, we’d make a soup or some mush out of it, whatever we could. There were times when I had to walk along the street gutters to pick up whatever I could to eat — apple cores, potatoes, mostly vegetables. I had to scrape them off, clean them up, wash and boil them — we knew these had to be boiled before they could be eaten. There were times we used to boil grass! Our family was that hungry. I’ve seen people suffer so much that they couldn’t move.

***

Religion was not supposed to be practiced in the USSR. As a youngster in Tajikistan I used to walk by some mosques, not knowing what they were except that they were holy places. I knew nothing at all about Islam. Some of the people wore something like a turban around their heads, and colourful coats with bands around their waists. It was only later, in North America, that I realized that these were people practicing their own religion, the Muslim religion. This was how little we knew about other religions, because officially, there was no religion in the Soviet Union.

And yet, I remember having my bar mitzvah, which must have been in 1944. We were living in a small hut made out of mud and water and straw (everybody lived in such a hut), with one little window. A few other Jews were over. My mother covered the window, so no one would see, and I said a few words in Hebrew. My mother made a sponge cake, and we had herring and a bottle of vodka. I don’t know where they got that stuff. It was done quietly, with no show. And that was it, that was my bar mitzvah.

An Unwelcome Return

Eventually, the war ended, and everybody celebrated. Supposedly, a deal had been made with the Soviet Union, with Stalin and Churchill, I think, that people should be able to return to the places they came from. So in early 1946, when I was fourteen years old, we went back to Poland.

When we got back to Poland, now under Soviet control, and stopped at various train stations, we could see and feel the hatred from the local population toward us. We could sense how angry they were that they couldn’t do anything to us. You could cut the tension with a knife! I felt not just unwelcome — I felt hated. I felt if I stayed in Poland I would be playing with my life. Of course, we knew at that point what had been done to the Jews during the war.

The only other survivor on my father’s side, his sister Laicha, had married and was now living in a city called Wrocław, Breslau in German. We stayed with her and her husband, but my parents wanted to go back to Będzin to see what was going on there and who was left. But there was nobody left. My father grew a moustache, something he had never had in his life; he had the idea that he wouldn’t look as Jewish with a moustache.

When my parents returned from Będzin, they told us that the landlords wanted us back and said we would be treated well. My parents asked me whether we wanted to stay or go on. They, especially my dad, always paid attention to what I had to say. I had absolutely no interest in staying in Poland. “Farvus vilstu nisht do zein?” (Why don’t you want to stay here?) they asked. I remembered the hatred after the war, like I could smell it — I didn’t want any part of it. Maybe my father didn’t absorb it like I did. For me, the answer was: Get out of here. Go to Palestine. By then, we were already hearing stories about Palestine, about Jews wanting to go there and some getting through. Getting to Palestine became the goal for many Jews, and it became our plan as well.

The Haganah, an underground Zionist military organization, was working in Europe by that time. To make our way to Palestine, we were supposed to cross into Czechoslovakia. We, along with other friends from Tajikistan who had come back to Poland, secretly made contacts with people in the Haganah. We had to gather all kinds of money to be able to make our move. I remember that my uncle, my father’s brother-in-law, sold a leather coat and a trench coat that had cost a fortune.

Once we got the money together, we went by train to Wałbrzych, Poland, near the Czech border,where the Haganah was operating. The arrangement was that we were to stay in that city for a day or two, then leave at nine o’clock at night to cross the border into Czechoslovakia. It wouldn’t be too far to walk to the border, and we were to cross it and keep walking until morning, when we got to a town with a huge circular fountain. We were to park ourselves around this fountain and wait for the people from the Haganah. The Czech police in the area would have apparently been “looked after,” bought off.

There were about thirty of us in this group, and we were ready. A friend of my parents, Chazkel, was part of this group. He told my parents that some of them were going a couple of hours earlier and he invited us to join them. My mother didn’t want to change plans. When we went across the next day at the appointed time, we found out that all the people who had gone before had been shot in the forest by Poles. People were shaking when we found out. And I remember my mother saying, “Oy, s’do a Got in himmel” (There is a God in heaven), since we didn’t go with them. We were so lucky. Even after the war, Poles, and others, like the Ukrainians, were killing Jews out of hatred.

At the border, my pants got caught on barbed wire and I couldn’t get free. My dad came over and just ripped my pants and we continued. We got to the town in Czechoslovakia at some point in the morning. At the fountain, some guys came by and spoke a little Yiddish. They were from the Haganah. Czech police were there, but they were given a package of this and that, probably cigarettes. We walked to a station and I think there were trucks that took us away from there. Then we went by train to Vienna.

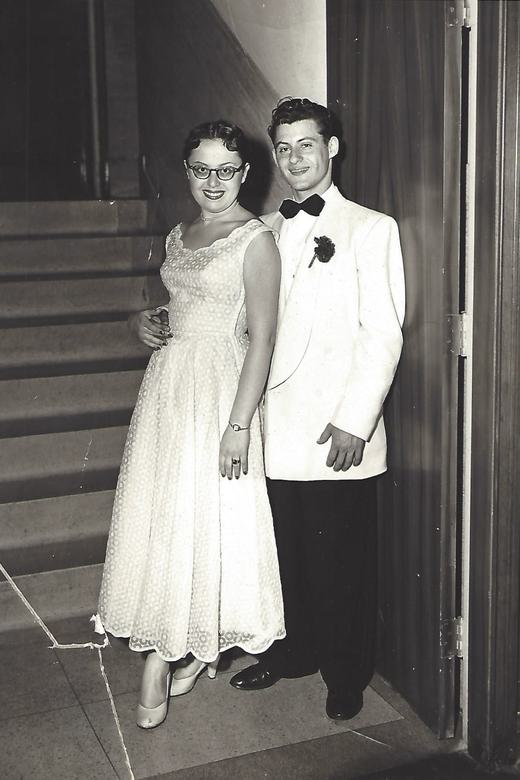

Philip and Joyce's wedding. Toronto, 1953.

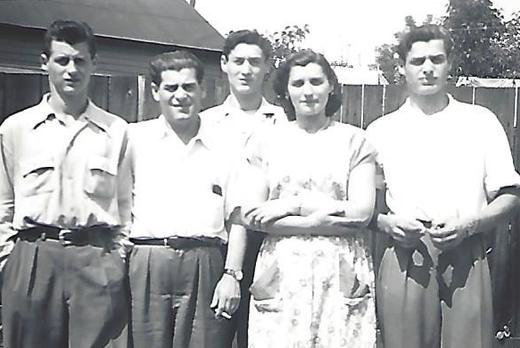

Philip and his family in Canada. Left to right: Philip, his father, Louis, his brother Saul, his mother, Helen, and his brother Morris. Toronto, 1949.

Philip playing violin in the Admont displaced persons camp. Austria, circa 1947.

How Fortunate

We stayed in Vienna for a couple of days, but we didn’t see much of the city. The authorities had to disperse people to different displaced persons (DP) camps. Austria was divided into four sections: Soviet, American, French and British. My family wound up being transferred to the British sector, and the camp was in a place called Admont.

Admont was a small town in a beautiful, picturesque area in the Austrian Alps. There were military barracks already in place in the camp. I guess the Germans might have used the barracks for training troops. I would estimate that there were over a thousand people in the DP camp, Jews from all over Europe. We were there for about two and a half years. The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) managed the camp and supplied the food. My father and other men were volunteer firefighters, and we youngsters went to school.

The school was held in one of the barracks. Our teachers were residents in the camp and taught us whatever they could. One teacher who taught history was marvellous; when the bell rang at the end of class, no one wanted to leave. He supplied the knowledge we young people were famished for. Before then we lived, I felt, like animals, with no information or knowledge. I had gotten some education in Kursk, but after that — apart from the very elementary schooling in Leninabad — it had been just travel.

Anyone who could play an instrument got together, and we formed an orchestra. My instrument was the violin. There was someone who played the piano, another the saxophone, a third the accordion, and yet another the trumpet (this fellow, I recall, always carried a gun in his back pocket). We played all kinds of music, and others sang. We played in concerts, at weddings and in plays.

Around 1947, some representatives came from Canada looking for tailors, so my parents registered. My mother had always wanted to come to Toronto because her father, whom she never knew, had died in Canada during World War I and was buried somewhere in Toronto. My parents attended some interviews in Graz and my mother said to the interviewer, in Yiddish, “I have a cousin in Toronto, Sam Wasserman, maybe you know him?” He was writing down things and didn’t even look up. Eventually he looked up and said, “Neyn, ikh kon nisht aza man.” (I don’t know anyone by that name.)

When we came to Toronto, my father wound up working as a tailor for the Posluns family, who were distant cousins of my mother’s. Although my parents didn’t know it at the time, it turned out that Samuel Posluns himself was the man who had interviewed them in Graz. And Sam, Shmuel Wasserman, my mother’s cousin, was working for him. When we came to Canada, we never approached Mr. Posluns for anything. We were what we were; he was what he was. Years afterwards, my mother would say, “We were so lucky he didn’t reject us.” My mother was never bitter about this, or about anybody or anything. They were wealthy mega-millionaires, and we were lucky to survive and come here. And we took it that way. There was no animosity.

We wound up in Canada because Israel had been impossible to get to, and we just wanted to get out of Europe. I wasn’t ever sorry that we never got to Palestine. It’s not that we didn’t want to go, but had we tried we might not have gotten there anyway, because the British were intercepting the vessels and redirecting them to Cyprus. Most of these people had to wait to get to Palestine until Israel was declared an independent state in 1948. But my parents and my brothers and I all felt that whatever came first would be fine. Canada was a brand-new country to us and an opportunity to better ourselves. We wanted freedom. Who cared where it was? We would have gone anywhere. It was freedom we wanted.

***

I was always a fiery guy, but I settled down. I was going to change the world by the time I was forty-five years old, but of course I gave up. I got smarter; eventually I realized: it is what it is. Now, I’m not so much involved. I’ve gotten rid of my hatred through the years. I realized it was a very destructive emotion, so I don’t hate anymore. My attitude is, if I don’t like you, I don’t bother with you. I can’t be angry at anybody. I have no reason to be angry at you, or him, or the neighbour, or anybody else, certainly not the Almighty. That’s just the way life is. If something rubs me the wrong way, I just walk away from it; I don’t have to prove anything to anyone. It’s as simple as that.

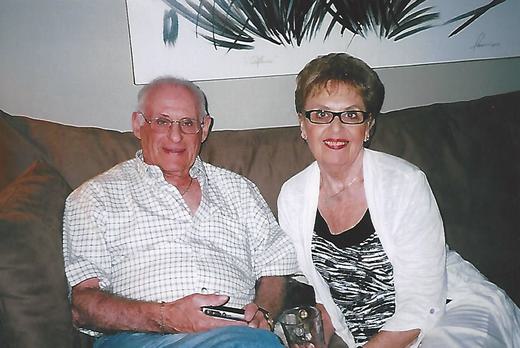

I consider myself one of the luckiest people in the world to have come to Canada; I made a life, enjoyed a good number of years with my parents, my brothers, my relatives, friends, neighbours. I was so lucky to have met my wife, Joyce.

All the losses still hurt me, even though I know loss is inevitable. I know it’s the law of nature, the law of life. At the same time, when I think about the past, my wife, my brothers, my family, I think, how fortunate we were, how fortunate.

Philip Tabachnick with his Sustaining Memories writing partner, Annabelle Sabloff. Toronto, 2013.

Philip and Joyce. Toronto, circa 2007.

Philip at the Roselawn Cemetery beside the gravestone of his maternal grandfather, Pinchas Lazar Grossman, who passed away circa 1916. Toronto, 2013.