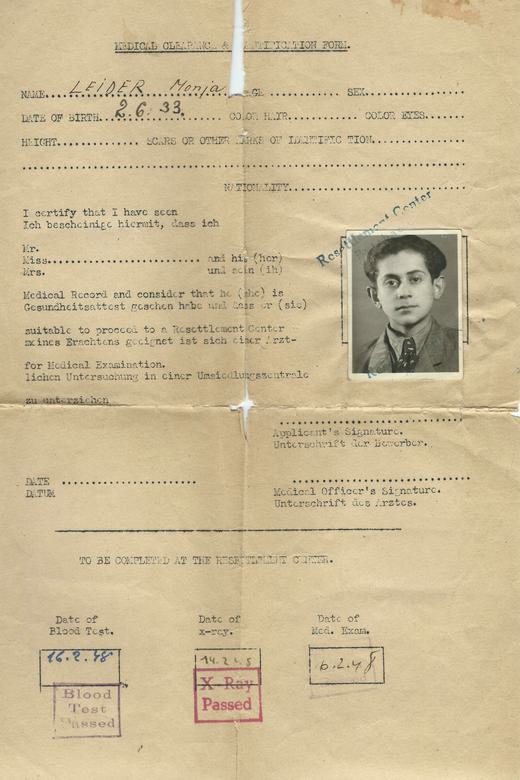

Morris Leider

Born: Brody, Poland (now Ukraine), 1933

Wartime experience: Ghetto, escape, hiding

Writing partner: Peter Bloch-Hansen

Morris (Munia) Leider was born in Brody, Poland (now Ukraine), in 1933. At the start of World War II, Brody was occupied first by the Soviet Union and then by Germany in 1941.

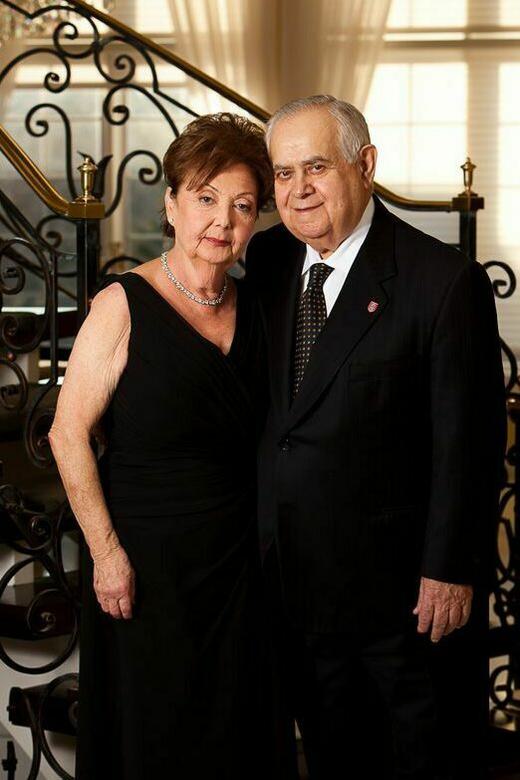

After the German invasion, Morris and his parents went into hiding in the forest north of the town but were found four months later and sent to the Brody ghetto. Morris and his father subsequently escaped to the forest where they were later joined by his mother. They were part of a large group of partisans, and Morris helped by gathering or stealing food and serving as a lookout. His sister, Henusia (Helen), was born in the forest in 1943. Morris and his family survived in the forest until the area was liberated in the summer of 1944. After the war, his family left Poland and lived briefly in Austria and then in Germany, where his brother, Szymon-Majer (Simon), was born. Morris, his parents and his siblings came to Canada in 1948, settling in Toronto, where Morris worked in Kensington Market and then, in the late 1950s, opened and ran his own business, European Quality Meats & Sausages. In 1966, he married Dina Kenigsberg and they raised a family together. Morris was acknowledged for his charity work for several organizations in Toronto. Morris Leider passed away in March 2021.

Adventures of Youth

I went to Grade 2 at the Jewish school in Brody, Poland (now Ukraine), before the Soviets came in 1939 and sent me back to Grade 1 because they had a different system. I got back to Grade 2 just as the Germans came, and that was the end of my schooling during the war. So at age seven, I had no school. Usually, Polish children only went as far as Grade 4 anyway, unless they were very rich; it was thought the rest of us only needed to be able to read a little bit. Without education, you had to have farmland or some other means of income, but even before the war, Jewish people were restricted in land ownership, so many also became merchants and tradespeople — tailors and shoemakers and so on. If you were comfortable and quiet, the authorities left you alone, but if you were poor they thought you might be trouble.

My father, Rudolph, was a barber. He had a small shop and a good clientele. In those days there was no electricity in the shops; he used hand shears. He’d cut my hair when he had time. We had a one-storey house with a tin roof (which cost a lot more than thatch) in a small town just outside Brody, and three acres of land north of the city near the Boldurka River, about four kilometres from the house. Those three acres, on which we grew corn, wheat and potatoes, gave us enough food for the family and some to sell. We also had chickens, geese and four cows, and some gentiles helped us with the work. We made a very nice living with three acres.

Poles and Ukrainians mixed together in Brody, so sometimes I played with Polish children, sometimes with Ukrainians. The Ukrainian kids liked to go to their church and ring the bells. I used to go in and hang onto the rope too, swinging there, ringing the bells, until my maternal grandfather, Myer, would get a hold of me and take me home by the ear. At that age, kids don’t think about religion much, but sometimes, if the others didn’t like something about me, they called me “Jew” and things like that, or they’d just refuse to have anything to do with me, but they never beat me up or anything. I was never scared.

***

I was trouble from the start — full of mischief, a riot in the street, misbehaving in school, but because I was the only child I got away with it.

Once, when I saw a woman milking a cow, I shot her with a slingshot, spilling her clay pail of milk. Wanting to avoid trouble, I went out to a pasture and looked for a friendly horse. Finding one, I took it over to a fence, climbed up on it and rode it, without a saddle, to my grandparents’ house, about fourteen or fifteen kilometres, an hour and a half or so, away. The road was sand with forest on either side, which they called the Black Forest. When I arrived there, my grandparents had to go all the way to the post office — the only place nearby that had a telephone — to call my parents. This all took long enough that, in the meantime, my mother was hysterical because I’d been seen in the pasture near the river and they thought I’d probably drowned.

Another time, I got on a boat in the river, and the paddle got stuck in the mud, leaving me drifting for a good three and a half kilometres. I also used to bring home stray dogs. I was always getting into trouble; it was just one thing after the other with me. I remember hitting a horse with a stick once, just because. It was surprised and kicked me in the stomach and both legs, sending me into the manure. I was lying there about two and a half hours, trying to catch my breath, but those farm horses didn’t have any shoes, so I wasn’t seriously injured. Another time, a horse and wagon ran over my legs. I used to take a beating, but maybe that toughened me up. I had a lot of fun as a boy.

In the Forest

I was too young to realize what was happening when the Germans first invaded Poland in 1939. A lot of Jews were running away toward the Soviet-occupied regions of Poland, where we lived. A woman came over to our house and said the Germans were killing Jews and that Jews were running away from Lodz and other places. My grandfather said, “Killing Jews? Jews are running away because they don’t want to work. Germans are too civilized to do things like that.” He died just before the German order to establish ghettos.

In the days before the German troops arrived in Brody in the summer of 1941, we’d go to sleep and the bombers would fly over. I remember the noise and the ground shaking. One day, when a German observer plane flew over us, a Soviet shot the pilot with a rifle, and the plane went down. The Soviets wanted revenge for the Germans’ betrayal. Our house was burned to the ground during this time.

When the Germans started taking Jews away, the commandant, a captain I think, said he would try to keep my father around because he was useful. But one day he came out of the Gestapo office and warned my father by saying, “Leider, disappear.”

So right away we went into the forest north of the city. That was in December 1941. I remember the snow. We hid there — my father, my mother, her brothers, and several other people — in a dugout with logs over it, for about four months, until we were found. A man who went into the forest to check on the animals and things like that saw us and reported us to the Germans. Apparently he got two or three pounds of sugar for that. Then a group led by a drunken sergeant arrived and put guns right down into the hole, yelling, “Come out!” My father had cut this sergeant’s hair and knew he was really vicious when he was drunk, so we climbed out. The sergeant took two people by the collar and shot them right there. When my mother’s brothers saw what was happening, they ran. He shot at them, but he was drunk and he missed. They later ended up in the ghetto and were eventually sent to a labour camp. The sergeant knew my father because of the haircuts, so they put us in a jail in town and shot the others — eight or nine people.

Then, for some reason, they sent us to another jail. “I trust you,” the man in charge told us, so we had no escort, nothing. We went to the second jail, and they put us in a room with about fifteen people. There was one window, I think about fourteen feet up, one light bulb hanging down and no washroom, only wooden benches to lie down on. It was unbearable. Some of the guards felt bad for us and threw us some bread. It was around April now, though there was still snow.

They eventually marched us to the ghetto. We were fed a little bit there. You get hardened after a while when you see people falling over and dying every day, just lying there until the wagons came and picked them up. My father often snuck out under the wires at night to get food from farmers who’d been his customers, and at one point he realized the Ukrainians were being paid to dig big trenches for mass graves. He came back saying, “Let’s get out.” So my father and I ran to the west through farm country and into the forest, then worked our way around to the north. My mother, who was sick when we left, came out to us a little after, but her sister-in-law Laya was taken away and perished.

We didn’t go to the bunkers where we’d been before because there you had no escape; the Germans could just throw a hand grenade down. So we lived on top of the ground. There were no lights, and it was very cold, but we made tents out of potato sacks. If we heard a noise at night, which we often did, everybody ran in different directions, so we were tired all the time. I went out to the farms looking for food, taking the rotten potatoes and bread the farmers threw out to their pigs. With pigs you have to be very fast because if they bite you, you could lose an arm. I would watch until the pig had its mouth full, then put my hand in, grab the potatoes, put them in a sack and run back into the forest. Sometimes I went up to the houses and asked for food. Through the windows I’d see children I used to play with, there in their warm houses, ready for bed in their long shirts, while I was outside in the cold and snow. Sometimes I was chased away, but some children said, “Stay outside and I’ll give you something.” I supported my family at ten years old.

***

In the winter, there was no place to take a bath or a shower, so I didn’t bathe for three months at a time. We melted snow for drinking water and cooking, but we were filthy and suffered greatly from lice. In summer it was different. You could take an anthill apart and put your shirt in. The ants cleaned out the lice in five minutes. The river used to dry up a bit in summer, and all the frogs and slime sat on top of the remaining water. I remember moving the slime and the frogs and everything else away with my hat because there wasn’t anywhere else we could go for water. We couldn’t go too close to the farms because the farmers would shoot at us, although some of the Ukrainian farmers put out bread. Others, whom we’d grown up with, now wanted to kill us. After they ploughed their fields, we’d go out and pick up potatoes they’d missed. Later we had guns, and we’d go to the farms at night and take extra, as much as we could.

Things were very disorganized in the forest. Every day one or two of us were killed, but toward the end we grew stronger; we got weapons and put up a fight. There were escaped Soviet prisoners of war with us. We didn’t make any organized attacks, but if Germans came into the forest, we shot them.

When you’re eleven years old and you’re carrying a gun, I can tell you, you feel like you’re six feet tall. I had one of those German automatic rifles that held thirty bullets. I thought I’d put an extra one in the barrel, but it got stuck and exploded. After that, I didn’t try to put any extra bullets in my gun. I used to throw hand grenades that we’d found into the water to stun the fish. They’d float to the surface and I’d pick them up quickly and put them in a bag. The Luger was a good weapon too, but its weight pulled your pants down when it was in your pocket.

After a while, the Germans were afraid to come into the forest, so they’d send some Hungarians or Romanians in, collaborators. They spoke a different language, and for good reason, we didn’t trust them. We killed some, hung them up, cut their throats, took their guns. We didn’t take any prisoners.

But we were always frightened. We constantly moved around to different areas in the forest, which was so thick we always had scratches on our faces. The only comfort we had was a fire, but just before the Soviets came back, the Germans started bombing wherever they saw fires, so no more of that. We couldn’t get out to look for food or to get a drink of water, so for two weeks we ate raw mushrooms, which have a lot of water in them. I was a skeleton at the end of the war. My father could never eat mushrooms again, and you know, I never throw a dry piece of bread away. I’ll soak it and give it to the birds.

You get hardened after a while when you see people falling over and dying every day.

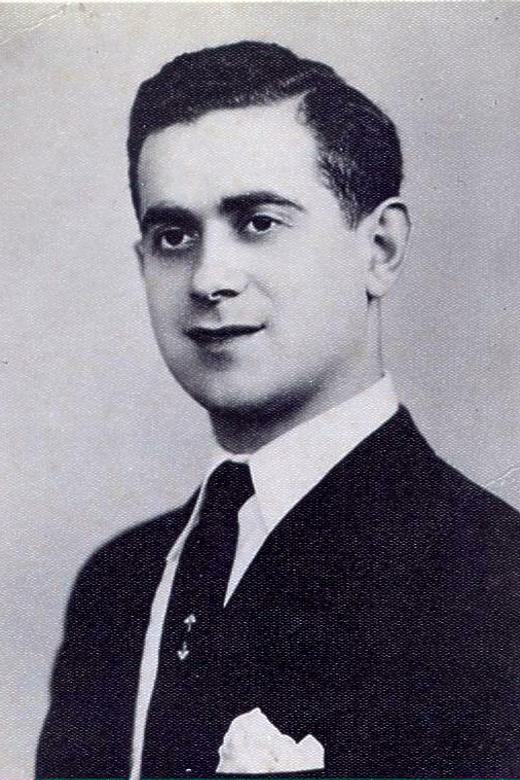

A New Life of Achievements

The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), which was a Jewish aid organization, smuggled us out of Poland to Czechoslovakia and then to Austria because there was still so much antisemitism in Poland; Jews were being killed even after the war. We stayed in Austria for about five or six weeks before being moved to Wiesbaden, Germany, near Frankfurt, in the American zone. The Americans kept the Germans’ heads down, so we lived openly there, in tents for a while, before we were given housing.

I was very independent, so I separated from my parents and ended up in a camp waiting to be sent to Israel as an orphan. I wasn’t yet sixteen. When my parents found out what was going on, unsurprisingly, they wouldn’t sign the papers for me to go.

In Germany, I was put in Grade 6 in a local school. When the teacher put algebra on the board, I didn’t understand it and everybody laughed at me. I was small, undernourished and didn’t say anything, but when I turned around to this Soviet kid who was laughing, he squirted me in the face with ink from his pen. So I got up, walked over to the teacher’s desk and poured ink on his head. He was stunned. I picked up my bag, which had a gun in it, and went home. Growing up like I had, I’d become kind of toughened.

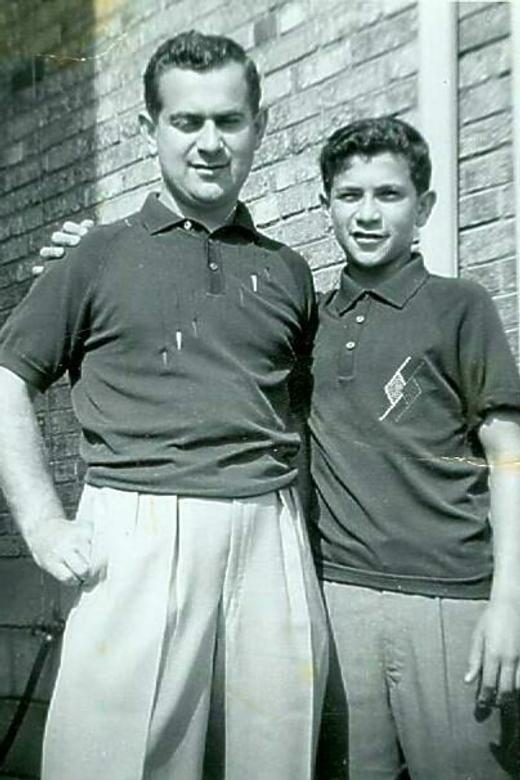

My mother had a brother and a sister in Canada. They’d left Europe before the war and were now a big family in their new country. They all contributed what they could and sponsored us to join them. We travelled by boat from Germany to Quebec City and then took the train to Toronto. We arrived in the summer of 1948, when my brother was about two or three years old and my sister was five. We stayed with my aunt Faye and her husband, Teddy, who lived in Pontypool, a small Ontario village. Aunt Faye had a dress store and cigar store with pool tables, so I worked in the snack bar there twelve or fourteen hours a day, with no pay.

When my aunt moved to Toronto, to Kingston Road and Main Street, we moved with her. She said she was going to send me to school, at the age of fifteen, to be a lawyer, but she changed her mind. I did go to school for a while, though, where I was put in Grade 7. I was asked, “What are we going to call you?” My Polish name was Munia. “Nobody says that here,” they said, so I became Morris. I was very good in school, but I’d grown up with older people, with a gun in my hand, and I didn’t take no for an answer, so I didn’t fit in. Everybody was trying to teach me how to speak English, but they laughed at my efforts. When the other kids were playing soccer, I just went and kicked the ball around because I didn’t know the rules yet, and they laughed at me some more. When I was sixteen, the principal, who was an antisemite, told me I’d be more comfortable downtown where there were more European people. The principal was god in those days, so I quit school and set out to help support my struggling family. Years later, I would joke with my kids and tell them that I could’ve become a doctor. When they asked what stopped me, I’d say, “Grade 7.”

***

We opened up European Quality Meats & Sausages on November 15, 1959, on Baldwin Street in Kensington Market. We took in fifty-eight dollars the first day, and expenses were a hundred and ten. I think we took in thirteen hundred dollars that Christmas, though. On January 8, the wife of my business partner, Yoshe, came in and said, “Let’s split the profits.” Well, there were people to pay, rent to pay, improvements to make to the store for the meat inspector. There were no profits yet. Yoshe didn’t come back to work. I went to my parents for money and bought him out. He gave me the name of another butcher, who began to teach me. I didn’t even have a truck, so I’d open the top of my convertible and do pick-ups and deliveries that way.

I worked until ten o’clock at night, painted the ceiling, did everything, but I really didn’t know what I was doing in that business for quite awhile, and things were really bad. If I didn’t have enough business I couldn’t sleep, and if I had too much business, I couldn’t sleep because I was working overtime to fill the orders. By 1963, the store’s bank account was overdrawn by twenty-three thousand dollars. I was using the same bank that I’d dealt with for the creamery, and the manager knew me and said, “I have confidence in you.” But when he was replaced, the new manager came in, looked at my account, my premises, and wanted to close me down. But there was no value for the bank to take, and since my debt wasn’t increasing at that point, they let me continue to operate.

It got so there was often a lineup outside the store. We had to let ten people out, ten people in so it wouldn’t be too crowded to spot the pickpockets. There was a young plainclothes policeman there most days, watching for a few hours as a favour to me. He wouldn’t see anything, but I could spot a pickpocket right away, so I’d make the arrest. How could I spot them? I’d had to do that for a living. I could see what they were up to as soon as they came in.

That store was doing nine million dollars a year in sales when I sold it in 2011, but around 1994, I’d opened another location at Kipling and the Queensway that’s always done very well. We also have a plant in Brampton, about 52,000 square feet. I have employees who’ve been with me for forty-three years.

I’m eighty-one and I’m still working. My son, Larry, and my nephew Mike work with me. My daughter, Sandy, a lawyer, is also working with me. She could make three times as much working someplace else, but I’m not taking anything with me. I get up at five o’clock, and by six I’ve had my coffee and I’m operational. I started this morning at five-thirty. My son tells my wife, “I don’t think my dad is human. I have trouble following him around.” My wife says that if I retire, I’ll just look for another job. I don’t know what it is, but I can’t sit still.

***

Over the years of operating the stores I became friends with young guys in the police department. They grew up and became senior officers, and through them I became a founding member of the board of the Ontario Association of Crime Stoppers for eighteen years. I didn’t look for any favours; I could have had tickets fixed but I didn’t, and they trusted me. I’m one of five civilians who’ve been awarded the badge of honorary chief of police; two of the others have passed away. I’ve also been honoured for my charity work with St. John Ambulance and other organizations. With their recommendation, I became a member of the Royal Canadian Military Institute, and in 2013 I received a certificate from Parliament in Ottawa recognizing my achievements and contribution to this country.