Mary Gale

Born: Lodz, Poland, 1926

Wartime experience: Ghetto and camps; false identity

Writing partner: Ruth Krongold

Mary Gale was born as Miriam Cymerman (Zimmerman) in Lodz, Poland, in 1926. When World War II began, her father arranged for the family to move from Lodz to Warsaw, which he believed would be safer.

Mary lived with her parents, grandparents and sister in the Warsaw ghetto and helped the Polish underground, delivering illegal newspapers. In the spring of 1943, they were able to escape the Warsaw ghetto through the help of Krystyne Panek, a Polish gentile who had worked with Mary’s father. Krystyne obtained false identification papers for Mary, her mother and sister so they could pass as Christians, changing Mary’s name from Miriam to Mary Plochocka. In the fall of 1944, while living on the “Aryan” side of Warsaw, Mary, her mother and sister were arrested and taken by train to the Ravensbrück concentration camp, classified as political prisoners instead of Jews thanks to their fake papers. Subsequently they were sent to Buchenwald, where they remained together, working in a munitions factory. After surviving a death march to Plzeň, Czechoslovakia (now Czech Republic), the three women ended up at a displaced persons camp in Aschaffenburg, Germany. There, Mary met Arthur Gale, a gentile Canadian colonel who was the director of the Aschaffenburg DP camp, and they moved to Canada and married in 1946. When her husband died, Mary pursued a degree at age forty-eight and worked in early childhood education for over two decades. Forced to live a double life as a Christian during the war, Mary could not bring herself to admit to her children and friends that she was Jewish until she was in her eighties. Mary Gale passed away in 2018.

A Loving Family

I was born into a loving Jewish family in the industrial city of Lodz, Poland. The city was not a beautiful place, but it was home. My sister, Halina (Chaya in Hebrew, and later called Helen on her false papers), was three years old when I was born. We were close, and my mother stayed at home, looking after us in every possible way. My mother, who was named Risella or Rosalia, managed the house while my father, Menachem Shloma Cymerman, worked in the textile industry. My father was the son of Chaim and Chudesa Lapon Cymerman, who also lived in Lodz. My father was a respected member of the community and had a successful business manufacturing raincoats, which provided us with a decent middle-class lifestyle. Although the times were difficult economically during the Depression and money was scarce, I was a very well-loved child.

Our parents gave us everything they could to encourage our development. We were taught tolerance at a very young age and had friends of different religions and backgrounds. If a certain child, Julie for example, was not well-liked at school or in the community, my parents would say, “What about this one? What about Julie? Ask her over for your birthday.” My parents taught us that we were not to be cruel, even when other kids could be.

My mother’s parents, David and Tyla Graff, lived with us in Lodz. I was very close to my maternal grandfather. I still have his picture, and to me this picture is worth a million dollars. He always had time for me; he sang songs with me and told me stories. He was always there for me. My grandfather was a good man and well known in the community. He was the director of a bank and was involved in the B’nai Brith orphanage. He found that the orphanage was being run dishonestly and that money meant for charity was being used by dishonest people. I believe that it was this that really killed him: he took the bad running of the orphanage to heart and died of a heart attack before the war when I was nine years old.

Once a year, we used to go to synagogue in our special clothes for the High Holidays, Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. Later, during the occupation in Lodz, the Nazis destroyed nearly all the synagogues in the city. Every Friday evening, we had Shabbat supper with our grandparents. We dressed up and went by droschka, a cart drawn by horses, to my grandfather’s house. He was so thrilled to have grandchildren. There were only the two of us. He was just in heaven. My grandfather had a velour jacket that he wore especially for the Sabbath and was fussy about twirling his moustache just so on both sides. We lit the candles and had wine and challah.

My family members were all good to me, but I could do nothing wrong in my grandfather’s eyes. He travelled quite a bit to Germany and when he returned, he brought me a big teddy bear on wheels that made a noise. Whenever I tried to sneak food that was not kosher, he would say, “It is not what you eat but what you do that counts.” My grandfather always supported me and taught me that a person’s actions and who they are inside are more important than how they look or any material things that they might have. I tried to teach this lesson to my own children and raise them with love. I wanted them to be good people and not judge others by skin colour but to look, rather, at what people think and do. This, my grandfather taught me.

Mary’s father, Menachem Shloma Cymerman, before the war. Lodz, Poland, date unknown.

Mary's mother, Rosalia (Jadwiga) Cymerman, before the war. Lodz, Poland, date unknown.

Working with the Underground

My father had a wonderful contact, Krystyne Panek, through his work. She was a good person who saved our lives. I would not be alive, telling this story, if not for Krystyne. At the time of the Lodz ghetto, anyone who helped Jews could be killed, along with their entire family. In spite of this terrible threat of execution to herself and her family, Krystyne was willing to help my father and his family. She took responsibility for us and put herself in grave danger providing us with care and protection. She got my father false Christian identification papers and made it possible for us to get out of Lodz and find relative “safety” in Warsaw.

Living in the Warsaw ghetto was horrible. We lived in very cramped conditions in the enclosed area designated for Jews, which didn’t increase even as the Jewish population living there tripled. No food was allowed in or out of the ghetto. People were dying of starvation because there was nothing to buy or sell in the ghetto. Both Jews and Poles had nothing, and we could only trade for a bit of food. It was common to see a person holding a dead child in the street and there was nothing we could do to help anyone. We just hoped that somehow my father could stop this terrible misery and find an avenue to get us out of the ghetto to safety. We spent a long time in the Warsaw ghetto, and during this entire time my father was the only one who had false Christian identity papers.

Food was procured only with ingenious plans. My father had contacts and business associates outside the ghetto on the “Aryan” side and managed to run a carbide business. He went undercover and I joined him in the activities of smuggling food. We had two identical briefcases and I carried one with money and exchanged it for an identical one with food to share with my family. I believe that on Ogrodowa Street near the courthouse was a gate that one had to pass through to get in and out of the ghetto. It was possible to sneak into this building and exchange the suitcases. Somehow my father was able to get us a little food or soup. Since, with my blond hair and blue eyes, I didn’t look Jewish, I became the best choice as a food smuggler for our family. Instead of dollars and cents we traded bread and butter. We traded anything to keep us fed and alive. I felt an overwhelming sense of responsibility to provide the food my family needed to stay alive.

The “Aryans” who helped did so unofficially, on the black market. Many people were smugglers in the ghetto. Little tunnels were built under the wall and children went out to get some supplies or a bit of bread from contacts on the “Aryan” side. It is difficult to imagine how these children felt! Every day, every minute, they were trying to survive and to help their families live. Fear was always present. The Nazis shot little children going in and out of the ghetto and sneaking under the wall. The guards were patrolling all the time, day and night, and lights were always shining. It was like a jail without the lock and key. Most people simply could not get out of the ghetto without getting shot.

By May 1942, the underground resistance movement was in full swing in occupied Poland. Everybody was doing something to fight the enemy. We were working with the Polish underground organization Armia Krajowa, or AK. My job was to deliver the illegal newspapers that my mother had brought home, which was very dangerous. If I was caught, it meant death. The newspapers were very small and were printed on duplicating paper as thin as tissue paper. One particular night, my mother brought home over a hundred copies. I had a peculiar feeling that something was going to happen and asked my mother to hide the papers as well as possible for the night. We put them in the bottom of a straw basket that was always used for laundry, filled the basket with dirty clothes and put it out on the balcony.

Night was always the worst time for German raids and searches. My sister and I kept watch every night by the window and on this night she watched from 12:00 to 3:00 a.m. and I watched from 3:00 to 6:00 a.m. During my watch, at 4:30, I heard trucks coming down the street toward our apartment. A truck stopped outside our house and four Germans walked out. My heart stopped beating. At once, I woke up my mother and told her what was happening. Then I jumped into my bed so that I could pretend that I was fast asleep when they came in. Five minutes later, someone was knocking at the door. I heard “Aufmachen!” (Open up!) and got up to let three of the Germans into the apartment. I suppose the fourth kept guard outside the entrance of the building. They said in a loud voice, “We know about you. You are working for the AK, those damn bandits! Where have you hidden the papers?”

I was very scared but I assured them quietly, “I do not know what you are talking about. I do not have anything to do with the AK. You must have the wrong information.” They did not believe me. “Who is living with you?” they asked.

“My mother and my sister,” I answered.

“Where are they?”

I led them to my mother’s bed. She woke up and said, “What’s that? We do not have anything to do with conspirators. Why did you come here?”

The Germans started to laugh. “All of you say same thing. Make the search.”

They started to look everywhere — in all the drawers, cupboards, in wardrobes and under the bed. In a few minutes our living quarters were turned upside down. I only prayed, “Dear God, do not let them find the papers.” I was shivering with fright. My teeth were clattering and I tried to stop with all my will so that the Germans would not know how scared I was. One of them walked to the balcony and I turned my head so that I would not see what happened next. I heard the balcony door open. It seemed like a very long time until he came back again. I felt that I was being tested. And then I heard, “No. Nothing here. But we will be back again. We will get you yet.”

Then they went away. I heard the heavy steps of army boots going down the stairway. Fainter and fainter they sounded. I then heard the motor start and they drove away. I felt like a big stone fell off my heart. My mother reminded me that soon I would be on the street delivering the papers. After an hour, we both were asleep. All that was left of our night visitors was the disorder of our room, with broken pictures and mirrors scattered on the floor. I wondered if someone had tipped off the Germans and told them we were Jews working for the AK.

I feel like I am on a seesaw and sometimes I think that it is too late to change my life story. It is very hard to face the people to whom I have lied. My secrets are hanging me and they are very hard to undo. I feel like they are choking me to death.

Double Identities

Many people who went out of the ghetto through the gate never came back. Every time I went out of our little room, my mother did not know if I would come back. She was constantly terrified. My sister was traumatized. She was older and understood more than I did about how terrible life had become. We decided that we could not live like this forever and wanted to go into hiding on the “Aryan” side with false papers. It was next to impossible to get “Aryan” papers that would allow us to leave the ghetto.

Eventually, my father managed to get false Christian papers for my mother, sister and me with the help of Krystyne Panek. The papers were bought from real people who were willing to share their identities for material gain. I became Mary Plochocka, the “cousin” of Krystyne Panek. My mother became my “auntie” Jadwiga Mozdrzvaske, and my sister became my “cousin” Helen. These new identities were unshakeable, and we never again called each other “sister” or “mother.” The three of us survived the war and never, during all that time, spoke of our true relationship. I can only imagine now how it must have pained my mother not to be able to call us her dear daughters after we left the Warsaw ghetto.

We left the ghetto in April 1943, just before the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. The rickshaw that took us out of the ghetto was organized by Krystyne Panek, who once again saved our lives. We saw the ghetto burning and smelled the smoke of the fires. The sky was so bright with fire that you could read by it. The Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising resisted the Germans for longer than all of Poland was able to resist when the Germans invaded in 1939.

Mary Gale’s and her mother’s camp numbers, as well as the red triangle that indicated being a political prisoner.

The jacket worn by Mary Gale in Buchenwald.

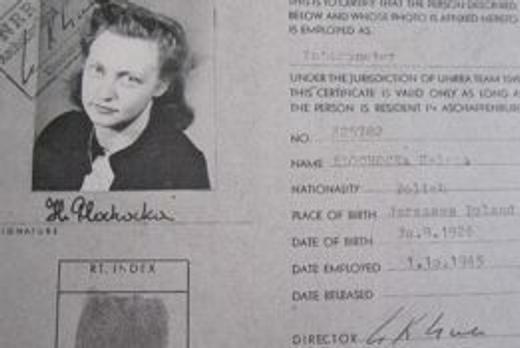

The work identification card for Mary Gale, under the name of Helena Maria Plochocka.

Ravensbrück 1944

The train took us to Ravensbrück, which was a concentration camp for women. When the transport arrived, prisoners were told to tie their left shoe to their right shoe so that they would be sure to find them when they came out of the camp shower, but most people did not find their shoes because they were killed. We three, my mother, sister and I, had Christian papers and were given the red triangle of political prisoners. I still have the triangle. We were also given numbers. Both were sewn onto our prison uniforms. Our classification stayed with us until the war ended.

My mother, sister and I stayed together in the camp. We did not understand where we were or what was going to happen to us. We always called each other by our Christian names and never used the word mother or sister. Mother was “auntie” who looked after me when my “mother” died of cancer, and my sister, Helen, was “cousin.”

Life in the camp was hell on earth. The goodness was beaten out of people. All we could do was to try to protect our little family of three and survive. I had been living in terrible fear as a food smuggler in Warsaw and felt completely responsible for my family’s safety and survival all the time that they were in hiding, so, strangely, I felt relief when I got to Ravensbrück. It is hard to believe that I felt relief in a concentration camp, but I had been so frightened in Warsaw that my family would be found and shot in front of me and that it would be my fault. At least in the camp, I thought, no more hiding in cupboards. I had felt like a hunted rabbit in Warsaw while my family hid. Now, at Ravensbrück, I felt we were all together trying to stay alive, and it was no longer my responsibility alone.

My mother, sister and I slept in the same barracks in Ravensbrück. Our beds were two wooden layers with straw between them. Every morning, we had to line up for Appell, roll call. Someone brought out a big metal pot of soup or coffee on wooden broomsticks and ladled out a portion for everyone. We had very little food — one piece of bread and one cup of watery soup or coffee in the morning. The kapos, prisoners who had been appointed supervisors, often ate our portion of bread.

Some prisoners killed for a little piece of bread. There were some good and some bad among the prisoners. Sometimes we could get someone to toast our bread and cut it into pieces to help us live on. At the time, I thought that the Germans put something in the coffee to stop our menstrual periods but later I learned that we stopped menstruating because of starvation. I weighed eighty pounds at the end of my time in the camps. We all suffered from malnutrition.

Mary and her future husband, Arthur Kendall Gale, at work in the Aschaffenburg displaced persons camp. Germany, circa 1946.

Mary and Arthur on their wedding day. Halifax, 1946.

Secrets and Fears

The man who became my husband, Arthur Kendall Gale, was a Canadian colonel who was appointed by the United Nations as the director of the Aschaffenburg displaced persons camp. He was like a god to me, as well as a judge and a teacher, and he was the only love of my life. As luck would have it, Arthur did not know any Polish, and I knew only about twenty words of English. He sat with his feet up on his desk looking for an interpreter from the crowd of hungry refugees and my hand shot up. I wanted the job partly because he was very attractive but mostly because of the two packages of Turkish cigarettes and loaf of bread that I would receive as payment for my work. It was the food that drove me, and when Gale asked me to turn around as part of the interview and then said, “You’ll do.” I was overjoyed to have the job. That is how I met my husband.

Even though I had no birth certificate at that time and had only the papers with my Christian name, Mary Plochocka, I still ask myself why I did not come out and say that I was a Zimmerman in the camp. I know that I was afraid then and I am still afraid now. I fear that if I say that I am a Jew, the hatred and horrors will return again. I know that this is what is in my head. We learned to be afraid when all around people were hanged, thrown out of windows, killed, poisoned; anything was possible. For me, Judaism became associated with tragedy, and I could not live as a Jew for that reason. The sad truth is that I have lied about my identity for almost all of my life, and it is very hard to change my story now. This memoir gives me the opportunity to tell the truth as I remember it.

***

Arthur Gale returned to Canada first, and I followed him at the age of nineteen with one suitcase in hand. He had been married before. Arthur joked that he was a cradle robber because he was thirteen years older than me. In 1946, we had a five-dollar wedding in Halifax; we couldn’t afford a taxi to and from the wedding, but we couldn’t have been happier. We lived in North Sydney, Nova Scotia, for a period of time before moving to Toronto, Ontario. Arthur had a small house-painting business after he left the army.

My mother married a Canadian and was able to get the appropriate papers to immigrate to Canada with me. Her second husband was an alcoholic and a very difficult man. Eventually, they divorced. She lived with me as my auntie until she died at the age of seventy-nine. My mother would have claimed her Jewish identity, but I was too scared, so we lived as Christians. My mother is buried in a Christian cemetery in Toronto with no mark on her tombstone or coffin that identifies her as Jewish. This causes me great sadness because I am certain that my mother self-identified as a Jew. Her grave betrays her connection with Judaism.

It is strange that I didn’t tell even friends or my family about my early life and experiences during the war until after my second trip back to Poland a few years ago. I always had a clever story to explain what happened to my family — the sad tale of the father who was a Polish general killed at Katyn, the mother who died of cancer and the auntie and cousin who adopted me. I feel very guilty about the emotional pain my mother suffered, living our family lies after the war, never able to simply say, “These are my daughters; these are my grandchildren.” I think of this all the time. But even now, when I want to tell the truth and correct the lies, I find that I skate away from telling people the truth about my life. I feel like I am on a seesaw and sometimes I think that it is too late to change my life story. It is very hard to face the people to whom I have lied. I am a very social person and I ask myself, “How can I tell my bridge friends that I have been lying to them for decades?” My secrets are hanging me and they are very hard to undo. I feel like they are choking me to death.

My children were raised not knowing their true religious identity. I wanted them to be “colour blind” when it came to skin or religious beliefs. It was quite a surprise to me when my son Tom decided to convert to Judaism. He was travelling from the university in Ottawa when he had a very serious car accident. The accident left him a paraplegic and he began to search for more meaning in life as he recovered. He researched many different religions but finally settled on Judaism. It took him five years of study to convert to a very strict form of Lubavitch Judaism. His wife and children also converted. During all those years of study, I never told him that he was born from a Jewish mother and that he did not have to convert. Tom changed his name to Gershon when he converted.

Gershon moved to Israel with his family and worked for the Jerusalem Post for twenty-five years. I visited Gershon and his family in Israel twice but revealed to him only a few years ago that I am Jewish. Gershon’s wife, Dinah, works very hard and takes good care of him and the children. It is like a miracle to me that of all the religions, Gershon picked Judaism. Maybe it was his destiny. It gives me pleasure that my daughter Anita is going out with a Jewish man who practises Jewish customs and that my granddaughter went to Israel on Birthright in January 2013. I am pleased that some members of my family are carrying on the Jewish traditions that I learned as a child.

I am now an old woman with many memories. More than seventy years have passed since my childhood ended at the age of thirteen. I live with stories and images from the Holocaust that are complicated and have repercussions in all aspects of my life. To this day, I am affected by triggers, nightmares and deep fears that something terrible will happen to me and my family if I admit that I am Jewish.