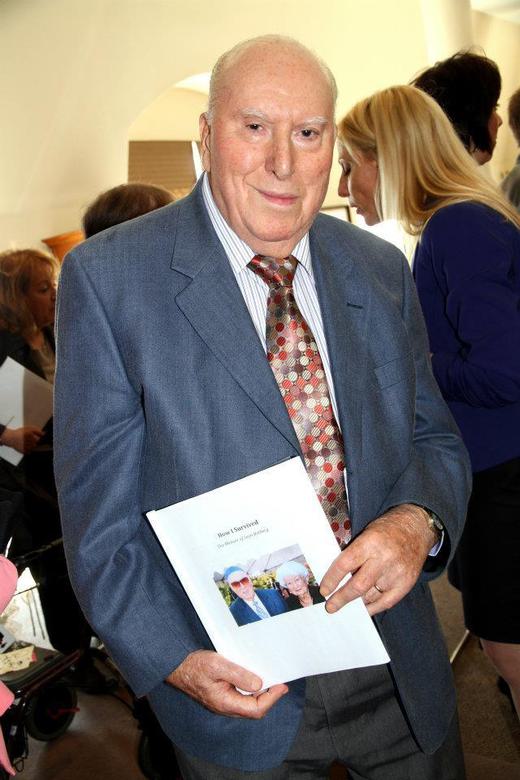

Leon Rotberg

Born: Lodz, Poland, 1920

Wartime experience: Ghetto, forced labour, camps

Writing partner: Fairlie Ritchie

Leon Rotberg was born in Lodz, Poland, in 1920. After the German occupation of Poland, he and his parents and three siblings were forced into the Lodz ghetto, in early 1940.

In the fall of 1940, Leon and one of his brothers were taken to a labour camp in Germany, near Frankfurt, to work on the Autobahn highway. Over the next three years, Leon worked in different factories and on farms in Germany, until he was deported, in September 1943, to Auschwitz-Birkenau. There, Leon worked as a slave labourer on electrical equipment for the company Allgemeine Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft (AEG). On January 18, 1945, the camp was evacuated, and Leon and his brother were part of a large death march from Auschwitz that took them to Gliwice, Poland, and then, by train, to the Buchenwald concentration camp. Leon was soon sent to Spaichingen, Germany, where he worked at an ammunition factory. The camp was evacuated after the factory was bombed, and Leon was liberated soon after by French forces on April 22, 1945. Leon reunited with his brothers, and they arrived in Canada in June 1948. Leon lived in Toronto and eventually moved to Brantford, where he and one of his brothers opened an iron and steel company, which they ran until 1975. Leon married Ethel in 1950, and they raised two children. Leon Rotberg passed away in 2013.

How Could Anyone Live Like That?

I was born in Lodz, Poland, on November 20, 1920. We were a family of six — I had two brothers, Jack, who was born in 1922, and Henry, born in 1925, and one sister, Baila, who was born in 1928. My parents were Solomon and Leah (née Bigeliesen). As far as I know, my mother was from Lodz, and my father was from the small town of Piotrków, near Lodz.

We were a middle-class family. Really, though, there wasn’t a true middle class there; there were just rich and poor people in Poland at that time. Our situation was closer to that of the poor people. Things had to be shared. Life was very primitive and poor because it was the Depression, and many times there wasn’t a piece of bread in the house. My father was a custom tailor; he had a store with materials in it, and people came to get made-to-measure clothing. When he could sell some suits, we were okay, but there wasn’t enough work for custom tailors during the Depression because people couldn’t afford to buy new clothes. But we survived somehow. We had meat sometimes, on a Saturday or Friday evening. I would go with my mother to the market to buy a goose, which did not cost much. She made schmaltz with the fat on the goose by cooking it and frying it. That sure was a treat.

I went to public school in the morning and in the afternoon I had Hebrew lessons at the cheder, a religiousHebrew school. After I turned twelve, I had to work. Lodz was a big textile centre, so jobs were available in that field. I worked in a textile factory as an apprentice. I used to sweep the floors, and then I started to work with the machines, but I was still really young. I made very little money, and often the factory owners could not pay me. Many times they didn’t have enough money to pay me because they would pay the gentiles and older workers first, since they were family men, thinking that young people like me could get by without until the next week. I worked there until I was eighteen or nineteen years of age.

***

In September 1939, my brother Jack and I were nineteen years old or older, which meant we were of military age. An order came that all able-bodied men were to go to Warsaw to defend the capital. We started to walk the hundred or so kilometres, but when we saw the slaughter on the way there, we turned back to Lodz. We were lucky that we turned back; most who got there were either killed or captured. The Polish army was no match for the German onslaught and collapsed after about thirty days.

When we returned to Lodz on September 8, there was hardly any movement in the city; it was like it was dead. It felt like there was hardly anyone there, that most people had left. The Germans were there, though. And eventually the city started to prosper because the Germans started to buy stuff and because of arms sales. And Polish people started to buy whatever they could because they knew their money would become worthless; for a while, people were able to sell their goods.

When the war started, we were living on the main street of Lodz, which we used to call Piotrkowska Street, and then the Germans came in and renamed it Adolf Hitler Strasse. When they marched into Lodz on September 8, 1939, it was a Friday, and the Germans who lived on the main street threw flowers at the German troops. We lived there, but soon we weren’t allowed to work — the Nazis didn’t allow it. We lived there but we weren’t allowed to work! How could anyone live like that? No Jews were even allowed to walk on Adolf Hitler Strasse, but how could we not walk on the street if we lived there? And the Nazis froze all the Jewish bank accounts so we couldn’t get any money from the banks. There was nothing we could do to survive; we couldn’t go to work because the Germans often grabbed people and made them work in some German establishment. Once, walking out to work, I was taken to the hospital to clean the toilets.

***

The propaganda in Germany was unreal. I picked a German newspaper out of the garbage and read Dr. Goebbels’s lies about how Jews cheat Germans in everyday life — so many lies against the Jews. There was a newspaper in Germany called Der Stürmer that was edited by a very famous Nazi, Julius Streicher; one headline in the newspaper read, “The Jews Are Our Misfortune.” There was propaganda about how the Jews controlled the banks and the government and the Jews this and the Jews that. A whole bunch of ridiculous lies.

The commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe, Hermann Göring, said that no foreign aircraft would penetrate their air space. And he said, “If they do, you can call me ‘Meier.’” (Meier meant “idiot.”) Eventually, after maybe six months, the Allies went in there and bombed Germany to hell. Göring lied through his teeth. He said all kinds of things like that. The whole German cabinet was a bunch of thieves. They came into a foreign country and robbed everything, stole everything they could. This was the war.

We were hungry, and people were starving. The German guards would shoot people who were just walking around. Killing people was a joke to them.

Finding Work

We lived on our street until early 1940. Then the Germans moved all the Jews into one part of Lodz, to a ghetto. There were about 200,000 Jews in Lodz before the onset of the war. Those of us who didn’t flee or hadn’t been deported elsewhere were rounded up and forced into an area of the city surrounded by a wire fence, guarded by German soldiers with machine guns. The Nazis created a Jewish administration — the Judenrat, or Jewish Council, as well as a Jewish police and a Jewish firefighting force. I lived there with my own family. We had a little storefront of a little building. We couldn’t buy any food, but there was water and electricity at this time. It was terrible there, and we were depressed. There weren’t any jobs. We were hungry and people were starving. The German guards would shoot people who were just walking around. Killing people was a joke to them.

I was in the ghetto for about six months, until September 1940. I couldn’t see any future there. When the Germans needed volunteers to go work in Germany, there was a charter provided for the ghetto that said a family would be paid twelve Reichsmark a week. The head of the Judenrat in the Lodz ghetto, Chaim Rumkowski, started recruiting young and strong people to go work in Germany, near Frankfurt. Both Jack and I left my parents and volunteered to work in Germany. I only wanted to go because the conditions were so bad in the ghetto. We were promised work and food, but they never paid us. We were lucky to have the food.

When I left the ghetto, I didn’t know what kind of work I would be doing. I was put in a railway car and arrived two or three days later in Germany. I was taken to some barracks in a camp that was located near Frankfurt. I started working to build a highway, what the Nazis called the Reichsautobahnen (now the Autobahn). I worked six days a week. Some people worked with wheelbarrows and shovels and broke their backs, and others who were a bit smarter and better organized got out of the worst work. I got a job working in the washrooms and boiler rooms, doing mechanical things, so I wasn’t exposed to the weather. I got my brother Jack a job in the kitchens. Getting to know the right people helped us find a little protection.

***

Our work changed often. The Germans took the road-building equipment and shipped it to the Soviet Union to build roads there for their trucks and tanks. Over the next couple of years, we worked in different factories and farms here and there. We were considered civilians until 1943. We got to eat, more or less, but we worried constantly about what was happening back home.

My youngest brother, Henry, was still in Lodz with my parents. I heard later that he was left behind when the Germans came in and took away the whole block and sent them to death camps. We had an uncle there and he came and picked him up. My uncle was a roofer, and since he did all the roofs in the ghetto he was a little protected too. My parents and my sister were taken to Chelmno from the ghetto in 1942. I never heard any more about what happened to them.

Then, in 1943, Germany was to be declared “free of Jews,” and no Jews were allowed on German soil. I was working on a farm at the time, and the director of the farm went to Berlin saying he needed the Jews because all the Germans were mobilized in the war and they were short of help. So the officials in Berlin told the director that we could stay, and we stayed on the farm for another six months. But then another order came, and he went again to Berlin, this time to no avail. So they sent us to Auschwitz. My number, 142491, is still on my arm.

We were put on cattle cars. The trip was about three days, and there were no toilets whatsoever. We arrived in Auschwitz in September of 1943.

How I Survived

We arrived at Auschwitz to a selection, orders to go this way or that way. They asked me what my profession was, and when I told them that I was a machinist they sent me in a particular direction. I didn’t know then that the other direction went directly to the gas chambers.

They gave us uniforms that looked like pyjamas, black and blue and grey pyjamas. Then they put us in tents, huge tents that housed new people. After that we stayed in unheated barracks. It was almost winter and at night we washed in big barrels of really cold water. In the morning we had to go, shirtless, to the one large washroom to wash ourselves. There was very little food — a piece of bread for the day and soup at night for supper that was made from turnips and water.

I eventually worked for Allgemeine Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft (AEG), working on electrical equipment. There were parts plants there and other plants that were making synthetic fuel. We were woken up at five in the morning to work and had to march there like soldiers. We went out divided into Kommandos, work groups, and there was a kapo, a supervisor. We worked until about eight o’clock. In the winter, we didn’t leave until it was daylight; they were afraid we could run away otherwise. There were a lot of beatings out there, and the prisoners who did manual labour were exposed to the weather.

I saw transports arrive in Auschwitz unloading men, women and children. The Nazis had wrecked their homes and businesses, and these people had brought all they had left with them — their diamonds, their gold, their cash. When they arrived in Auschwitz, the Germans told them to leave everything they had.

At that time the war was going badly for the Germans. They were turning back in North Africa. The U.S. was fighting against the Germans. We picked newspapers out of the garbage and saw that the Germans were saying that there were some big losses for their troops. The Germans agreed that they lost the whole 6th Army at Stalingrad. The general opinion was that every day another city fell back to the Soviets — Kiev (now Kyiv), Odessa and so on. We could see that the Germans were starting to lose.

***

I was in Auschwitz until January 18, 1945. Then the Germans liquidated the camp. At Auschwitz there was a big hospital for the prisoners with typhus and other illnesses. All of the sick got left behind, and all the able-bodied had to march. I was with Jack during this death march.

We walked to Gliwice (then called Gleiwitz), a city in Silesia. It was a big railway centre. It took a day and part of a night. On the march there I said to my brother Jack, “Let’s run away.” We were walking along the highway, and I was sure we could run into a barn on a farm and hide and afterwards somehow get ourselves machine guns. But he was afraid.

In Gliwice we were put in railway cars. There were maybe thirty or forty prisoners from Auschwitz in each car. People were pushing back and forth, trying to get into the middle. I stayed back at the end. There were maybe four thousand in all the cars. It was supposed to take us three or four days to reach Buchenwald. It took a week — and we didn’t have any food or water — because the rail lines were bombed and we had to go through Czechoslovakia. We went through many towns, maybe thirty, before we arrived in Buchenwald. Of the thousands of prisoners who left Auschwitz with us only a fraction arrived at Buchenwald; the rest had died during the journey.

Buchenwald was a camp built before the war for German political prisoners, Jews and even criminals. Now there were prisoners from other places there. They crowded them all together. At this time, the Germans were retreating all over Europe, and camps were being liquidated, with many prisoners ending up in Buchenwald.

There were so many dead people lying outside the barracks. There were no kitchens. There was no capacity to feed so many people. They gave us some bread. While we were there, the Americans bombed the nearby city of Weimar. Then the Germans took us there to fix the houses. Why would I care about fixing the houses? I looked for bread, jam or anything else to eat while I was there.

My brother Jack and I stayed in Buchenwald for about ten days. Then the Germans contacted the reconnaissance near the French border in the west, and we were sent out in about twelve railway cars. We lay on straw in the cars and didn’t have much to eat. We were told that they couldn’t give us anything because everything was rationed. We got a loaf of bread for three days, but it took us a week to get there. The hunger was terrible.

We arrived near the French border at the town of Spaichingen, at a subcamp of the Natzweiler concentration camp. There were a lot of French prisoners there, not Jews, but rather French partisans. We started to work in a factory making armaments, which were being used against England. We worked at night for about two weeks until the French came one night when we weren’t there and bombed the factory. There was nothing left. It was rubbish by the morning. After that, there were no jobs there. They gave us shovels to dig ditches in the ground. While we were working one day, a woman passing by threw an apple to us. One of the prisoners got the apple, and the guards shot him.

***

We stayed at Spaichingen for about another two or three weeks. We heard in the newspaper that the Allies had crossed the Rhine River. Even though that was hundreds of kilometres away from where we were, we knew the end was near. One day the Germans evacuated our camp. We asked where we were going and were told Berlin. But the Soviets had already occupied Berlin. The Germans were retreating and really didn’t know which way they were going.

Still, we walked on the highway toward Berlin. The SS walked with us. Not much happened. We walked for two or three days. We had blankets from the camp, but it rained and we were soaking wet. The nights were pitch black. We were so tired.

There was another fellow there from my hometown, and when I told him I had decided to run away and asked him if he wanted to come, he agreed. We jumped into a bush, fell down and then heard a couple of shots, but the prisoners and SS kept going.

We saw the highway and trucks with the Red Cross sign on the front. They were putting the wounded soldiers — the Germans, the French — in the trucks and taking them to the hospital. I was there in the bush for a couple of days. I went into nearby houses to find something to eat. One woman gave me a potato and bread. A couple of nights later, when I was in the bush, I heard a big explosion — the Germans were running away from the British. I woke up in the morning close to the highway and saw American and French troops. It sure felt pretty good. We walked out into the highway in our pajamas. And when the soldiers saw us, they must have already encountered prisoners like us before, because they started to throw bread and cheese to us. We were liberated by the French forces on April 22, 1945. We were free again.