Helen Roth

Born: Remete (Remetea), Romania, 1925

Wartime experience: Ghetto and camps

Writing partner: Marilyn Targonsky

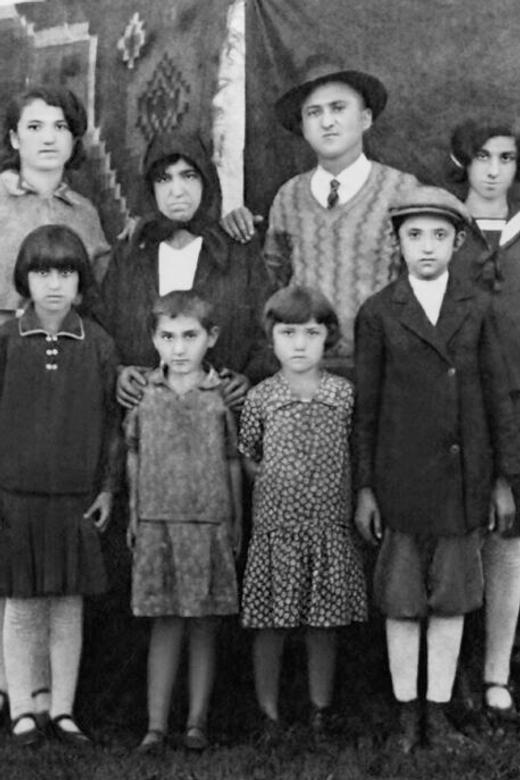

Helen Roth was born in Remete (Remetea), Romania, in 1925. She grew up in a large family, with six of her eight siblings.

In 1940, her hometown and the surrounding area came under Hungarian rule, and in 1944, after the German occupation of Hungary, she and her family were sent to a ghetto in Técső (Tetsch in Yiddish; previously Tacovo, Czechoslovakia, now Tyachiv, Ukraine). In the spring of 1944, Helen and some members of her family were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau; she and her sister Brauna were later deported to the Stutthof concentration camp and then to the forced labour subcamp of Pruszcz Gdański (Praust). In early 1945, as the Soviet army approached the area, the camp inmates were sent on a death march; Helen and her sister escaped from the march and were liberated by the Soviet army soon after. After the war ended, Helen and Brauna returned to their hometown and reunited with their surviving sister, Frieda. In 1946, Helen married Baruch Roth, and one year later they had their first child. In 1947, they fled Romania for Hungary and then Austria, where they lived in a displaced persons (DP) camp. They eventually arrived in the Pocking DP camp in Germany. In 1948, Helen and her new family immigrated to Israel, and in 1949 they arrived in Canada to join Helen’s brother, Itzik. Helen Roth passed away in 2017.

When I Was a Child

I was born Henya Davidovitch on June 12, 1925, in the fairly large village of Remete (Remit in Yiddish), in the region of Maramureș, Northern Transylvania. At that time, Transylvania was part of Romania, although before World War I, it had been part of Hungary within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The area was valued for its salt and petroleum resources. Remete was close to the borders of both Czechoslovakia and Ukraine, and a large percentage of the village’s population at that time was Jewish. Everybody knew each other. Now, there are no Jews remaining.

When I was a child, my neighbours were both Jewish and gentile, and we all lived together in harmony. Our daily interactions with gentile Romanians were civilized and peaceful. As children, we all played together and went to the same schools in the village. I had a very good childhood. My family was well off, and I was happy going to school, playing and enjoying the company of our nice neighbours.

During the regular school year, I attended a Romanian public school, but in the summer, when we had vacation, I went to cheder (religious elementary school) every day. We didn’t learn as much as girls learn now, but we did learn to read Hebrew, say the brachot (blessings before eating) and daven (pray) a little bit. Now I use a new siddur (prayer book) that tells me when to stand up or sit down during worship. Our parents and teachers made a much bigger issue of the boys’ education than they did of the girls’. Boys were sent to yeshiva. My brothers went to yeshiva starting when they were teenagers.

During my childhood, I was able to speak several languages. At school we spoke Romanian; while I was playing with the children outside, we all used Ukrainian to communicate; and in our house, Yiddish was the main language. When the Hungarians arrived, we started to speak Hungarian, too. I just picked it up. My ability to speak and understand these languages proved to be very useful in helping me survive the war experiences, the camps, and even in managing after the war ended. I still speak a lot of languages, but none perfectly. After the war, I even learned some Hebrew while I lived in Israel, but if you don’t use it, you lose it.

After the Hungarians took over in 1940, Jews were forbidden to go to public school, so I do not have much formal education, but you could say I had a Jewish education. Much of what I learned was from my family, at home. Nobody in my family or village knew any other way but to be observant. I still, to this day, keep kosher and observe Shabbes (the Sabbath). I bench licht (light and bless candles) every Shabbes. It is part of me.

But the arrival of the Hungarians changed everything drastically. They annexed Northern Transylvania in August of 1940 after they were awarded a large part of the region by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy as a reward for joining their alliance. Romania gave up our land peacefully, without any resistance, and we were left to fend for ourselves in the face of growing hardship. Not only were Jewish children no longer allowed to go to school, but we were no longer permitted to walk on the main roads; we had to go from one neighbour to another using the side streets.

The Hungarians took my family’s property. My family had been quite prosperous. We owned a lot of apple orchards and considerable land. We had lived on the proceeds from these apples by selling them to other businesses that then resold or used them. The purchasers would even pick the fruit themselves. We were like wholesalers. We even had a licence to make and sell slivovitz, fruit brandy. My mother totally depended on the orchards and the slivovitz for our family income. Now we couldn’t even go to our own orchards to pick an apple because the Hungarians had confiscated the land.

For four years, the rules imposed on us were very strict. Jews couldn’t own businesses or even go to work, although at first, we were allowed to stay in our own homes.

At this time, some of our Romanian neighbours became afraid. Some showed their underlying antisemitism, but others did offer to hide us if things got even worse.

My mother, Feige, was alone with us children. My father, Surel (Israel), had died when I was three years old, but I was spoiled and doted on as the baby with eight older siblings. By the time I was born, though, two of my sisters, Chana and Rivka, were already married and living in Belgium. I never knew them. They perished in the Holocaust. Two other sisters, Ruchel and Esther, were also married but lived nearby in the town of Tetsch (Tacovo), which had been a part of Czechoslovakia before the war (now Tyachiv, Ukraine), on the border with Transylvania.

My happiest memories are of being with my mother and brothers and sisters and the rest of the family. We were a very close family. In those days, my sisters Ruchel and Esther, along with their families, came to our home for Pesach (Passover) and all the holidays because they didn’t want my mother and I and the other young ones to be alone.

Of my eight siblings, only three survived the war.

My sister pinched my cheeks constantly so they would redden. That way, I would look healthier and wouldn’t be left behind when the workers were chosen to go to the labour camps. Those who weren’t strong or healthy would likely be gassed.

“Take Care of Each Other”

In mid-April 1944, on the day right after Pesach, my family was taken to the ghetto in Tetsch, then known as Técső, the town where my older sisters Ruchel and Esther lived, on the border with Romania. We weren’t given any time to prepare — not even to put away the Pesach dishes — and we could take only what we could carry in our hands. At this time, Hungary controlled Tetsch. We remained there for about six weeks. We were given very little, but knowing we had nothing, some of the neighbours brought us milk, even though this was not allowed.

Then, after about six weeks, around the holiday of Shavuos, we were loaded onto trains, fifty to sixty people in a car, packed in for three days, and taken to Auschwitz. The entire population of Jews in the Tetsch ghetto, approximately eight thousand, was deported to Auschwitz in the spring of 1944.

When we arrived at Auschwitz, we were immediately divided up — some sent to the right and some to the left. It was the last time I saw my mother, my grandmother, two of my sisters, and their seven children. The final words my mother said to me and my sister Brauna, who is two years older than me, were, “Take care of each other, kinder (children).” And we remembered her words always. These simple words helped us survive the next years.

After Brauna and I were sent in a different direction from the rest of our family, the Nazis took away our clothes and sent us to the showers. Imagine, us young girls, naked, while some man came and shaved us all over. Do you know how embarrassing that was? Then they gave us a shmatah (a rag) to wear. It didn’t matter if it fit or what condition it was in.

We were kept in Auschwitz for about two months after Shavuos. Of course, we didn’t have any calendars, so I don’t know the exact dates. We didn’t work there, but the living conditions were horrible. We were kept locked up in the camp and it was impossible to escape because of the electric barbed-wire fences and the guards.

Then the Nazis started to collect us to go to a work camp. Only after the war did we find out where we actually went — the Stutthof concentration camp, located near the village of Stutthof (now Sztutowo), just east of Danzig (now Gdańsk), then under German control. There were many smaller subcamps in the Stutthof camp system, and although it was officially a work camp, there was also a gas chamber and crematorium in the main camp. The living conditions were horrible. Each day, we were given a little bit of soup, which was terrible. It was made with something that felt and tasted like it had sand in it. And it gave us diarrhea.

My sister pinched my cheeks constantly so they would redden. That way, I would look healthier and wouldn’t be left behind when the workers were chosen to go to the labour camps. Those who weren’t strong or healthy would likely be gassed.

From Stutthof, we were taken to Pruszcz, a female-only camp and one of the work subcamps in the Stutthof system. Women were there from Poland, Romania, Hungary and other countries, too. There, we were allowed another shower and then were given striped uniforms. That shower was one of two we were allowed during the whole time we were there.

We worked with shovels and trowels, digging and paving landing strips for airplanes. My fingers became frostbitten because it was so cold, but I was afraid to say anything or complain because they would have just taken me back to Stutthof and sent me to the gas chamber. So I had to continue working, all the time hiding my frostbitten, swollen and blistered hands. As forced labourers we did physically hard work. Thankfully, my sister Brauna and I managed to stay together all the time and could help and support each other as much as possible.

In the mornings, we got black coffee and a slice of bread. Brauna and I knew we had to save one slice of bread for suppertime, so we shared one at breakfast. That is one way we worked together to survive. When we came back after the work day we had hot soup, and if one of us had a bigger potato than the other, we shared that, too. That’s another way we helped each other survive. If there was no soup, we shared the bread from breakfast. This was the only food we were given all day, but my mother’s words guided us always.

During work hours, we weren’t given anything to eat or drink. As we walked back and forth from our work location, if we saw someone throw out a potato peel, we’d try to steal it. That potato peel tasted so good, but had we been caught, we might have been shot.

***

As the spring of 1945 approached, the Germans running the camps started to march to the west, away from the approaching Soviet army. At first, we were left on a farm where we slept in the hay, but then the Germans took us on a death march, away from the advancing Soviets. The Germans didn’t want to let us go free even though it was already the end of the war. They could have let us stay there, just left us there. But no, they made us march ahead of the approaching Soviet soldiers so we wouldn’t be liberated.

If you could no longer walk, the Germans didn’t leave you behind alive. The soldiers took you to the side of the road and shot you. My sister and I could barely keep going. This was a death march and many people were dying.

After two or three days, Brauna and I realized we couldn’t continue walking. We had no strength or energy left. At night, we fell back further and further in the line so we wouldn’t be noticed by the German soldiers in the front. Then we snuck into the forest. I don’t know what we were thinking. It wasn’t long before a German soldier found us, and we thought, this is it, the end. But the Germans had many kinds of soldiers. One was the Wehrmacht, the army of regular uniformed forces, and there was also the SS, which was connected to Hitler. We were lucky that it was a Wehrmacht soldier who caught us. He took us to his superior officer on the military base, and this officer said, “What is the kinders’ (children’s) fault?”

These German soldiers saved us and took us into their care, but to our great disappointment, apparently they didn’t have any more food. The officer did give us a little blanket, something we hadn’t had the whole winter. We were still in Poland, I think near Gdańsk, I don’t know exactly where, but these German soldiers soon ran away because the Soviet army was approaching quickly. It became very quiet with no one there except one remaining soldier. He spoke to us in German, but we understood because we could speak Yiddish, which is similar. He told us he was going to put on civilian clothes and hide in the attic. He was going to act like one of us, as he wanted to stay with us.

Within ten minutes of the soldier going up to the attic, the Soviets arrived. They started screaming in Russian and, because we could speak some Ukrainian, we understood. They said they had already found other young survivors like us and asked if anyone was there, around the officer’s place. We said no because the hidden German had saved us, and we didn’t want to give him up to the Soviet soldiers.

For the Next Generations

It is for my grandchildren and great-grandchildren and the generations to come that I wanted to tell and record my story. I want to document the story of my life so my family can understand more about my experiences. I want them to know the importance of family and of helping each other always. They need to know my mother’s final words to Brauna and me.

I think it is important that all these life stories are told so that they become part of the recorded history of the Holocaust. When I heard that some people deny the Holocaust even happened, I decided my children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren should know the truth about what happened to me and others. God forbid anything like this should happen to them. I always told my own children about my experiences during the Holocaust, but my grandchildren and great-grandchildren need to know as well.

As I said before, the Hungarians took all the Jews from my hometown of Remete — not one was left. Nowadays, I don’t think the young people in that town know what a Jew is. It is important that there is some record of the Jews who lived there for so many years.

My nephew, Sam Davis, my brother Itzik’s son, wanted to see where we came from, so he travelled from Canada to Romania with his cousin, who speaks Romanian because her mother is from Bucharest. They went to the city hall in Remete and as soon as Sam told them who he was, the officials said they didn’t have any documents. They were afraid we wanted to reclaim our property. My nephew explained that he didn’t want to make any claims, he only wanted to see where his grandparents, his father and my family came from. After that, he was taken to the property and even allowed to go into our old house. The secretary from the city hall was very interested to see what was going on, so he took my nephew personally.

In the local cemetery, my father’s headstone remains. My nephew took a photograph of it.

I also want my family to know that in every group, every nationality, there are good people and bad people. There are several examples of this in my story — the German soldiers who saved us, the Romanian guide who returned for me and my baby when we fled Romania after the war, the neighbours in Remete. And there were those who were not good to us — some of our Romanian neighbours claimed they were Hungarian for generations dating from before World War I and were quite rotten after the Hungarians arrived during World War II, even though they hadn’t been so bad prior to that. The Hungarians who took over Transylvania were very strict and sometimes cruel, and there was extreme cruelty in every camp I was in.

My story especially shows the importance of family, of staying together and supporting each other. My mother’s final words, “Take care of each other, kinder,” were very simple but very meaningful. My children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren need to understand this. My mother’s plea to us will live on in the next generations.