Edith Kirshen

Born: Sighet (now Sighetu Marmației), Romania, 1926

Wartime experience: Ghetto and camps

Writing partner: Giny Shneiderman

Edith Kirshen (née Weisz) was born in 1926 in Sighet (now Sighetu Marmației), a city in Transylvania, then part of Romania. Edith was raised in a large, well-to-do religious family that was active in the Jewish communal life of the city.

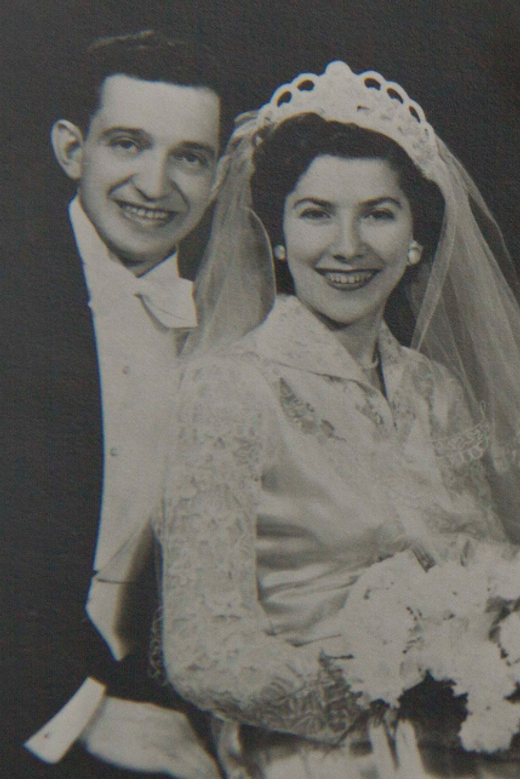

When Hungary annexed the area in 1940, the situation for Jews in Sighet worsened, and in 1944, when Germany invaded, Edith and her family were forced into a ghetto. In May 1944, they were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where most of her family was immediately sent to the gas chambers. Edith and two of her sisters, Aranka and Szeren, remained together. Edith was forced to do manual labour in Katowice, a town outside Auschwitz. In January 1945, camp inmates, including Edith and her sisters, were sent on a death march; they were then imprisoned in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp until they were liberated by British and Canadian troops on April 15, 1945. After liberation, Edith and her sisters remained in Bergen-Belsen until 1947 and then lived with a family in Augsburg, Germany. Edith and her sisters immigrated to Canada as domestics in 1948 and moved to Toronto, where Edith worked for two families and then worked in clothing factories. In 1953, she married Joseph (Joe) Kirshenworcel, whom she had met in Germany after the war, and together they raised a family. Edith (Elaine) Kirshen passed away in 2024.

Life Changed in Sighet

Our last Passover at home was in 1944. I remember I had to run to shul (synagogue). Somebody said there was going to be trouble there, so everybody had to go home. I had to climb over the fence of the shul to tell everybody the bad news.

Despite these events, our lives remained pretty normal until the Germans came; then the real troubles started. It is impossible to imagine how we survived.

We had affidavits to travel to the United States, but my father said that because he was doing so well he did not want to go. Then they closed the borders and Jews were no longer allowed to leave. Jews could not walk in the street after certain hours. There were meetings in our house, but we as children didn’t understand the situation. The adults did not let us hear the conversations. We were very protected and did not know what was going on.

My cousin married a young man from Poland and they and their son hid in our house, but we, the children, did not know that. We only knew that they were staying with us.

We had to wear the yellow star.

Then we had to go into the ghetto. The authorities did not give us much time. My father was the last person in Sighet taken into the ghetto because he had to finish his work for the high-class people in the city; he was their custom tailor. So we were the last family to go into the ghetto.

When we had to leave for the ghetto, Agnes, our maid, helped us. We could only take what we could carry and had to leave everything else behind. Before we left, my father, God rest his soul, buried two large trunks filled with diamonds, jewellery, gold, silver, brass and American dollars in the backyard. These trunks were the type people used to take with them when they travelled across the ocean. I am sure that somebody dug them up and took everything because after the war, when my sister Aranka went back home, she didn’t find anything. My father also hid things in the basement between the stairs. Aranka did find a few things there, including some American dollars. Later, in Canada, my aunt took the money to the bank to exchange it.

The authorities marched us into the ghetto in Sighet wearing the yellow star. We were there maybe a couple of weeks and then they took us to Auschwitz. I don’t remember our time in the ghetto much; it seems as if I have blocked it out of my mind. We were loaded like sardines into cattle cars. The doors closed and we left for Auschwitz. We had nothing — no food, no water, nothing. We did not talk much in the train; we did not know where we were being taken.

There was hardly any room to stand in the cattle cars. Children were crying; they were hungry and thirsty, and many wanted to go to the bathroom. We were not allowed out of the train until it stopped in Auschwitz.

It was very frightening. I had been born and lived in the same house my whole life; then, all of a sudden, my life changed completely. We were so naïve. It is impossible to believe that I survived everything that happened, but it was God’s will that I am here. Thank God, at least I have a family. I have a wonderful husband and two great sons, God bless them.

Praying to God

We worked in ditches, digging holes for water pipes. My feet were wet, and they got sunburned and blistered; I could not walk for days. I also had blisters in my mouth and could not eat. I crawled over to the road to throw bread to one of my cousins; she was supposed to bring me coffee made from burned bread. I dragged myself to the side of the road and then threw the bread, but she didn’t bring me the so-called coffee.

We were always hungry; we got almost nothing to eat. I don’t know how we survived. One day, when my sisters were sick, I met a girl who worked at the place where they separated the medicines. I told her, “You are my cousin, you have to help me,” and she brought me something for my sisters, thank God, and it helped them recover.

My brother-in-law, Moishe Fisher, Fanika’s husband, was also in Auschwitz. Aranka saw him in the concentration camp through the wires, and he had a picture of their baby with him. He was able to save his father from the gas chamber. I really don’t know how he did it because most of the men who were his father’s age were sent directly to death the moment they arrived. But two weeks before the war ended, Moshe died. He was such a good man. We miss him very much.

***

One day, walking back from work, we passed a field and the kapo said that we could pick something in the field to eat, so I took a few potatoes. But when we arrived in the camp and the SS guards found the potatoes, a guard hit me very hard on the head with the wooden part of the rifle. I can still feel the pain in my head; it has never left me. I truly believe that God saved me; otherwise I wouldn’t be here today. It was His hands that saved me.

In the camp we always prayed to God to help us. This is what kept us going. We could not think straight, and we could not plan for the future because we did not think we had one. We lived hour by hour, day by day.

One man who worked in a factory in Auschwitz gave me some knitting needles. I found a sweater, unravelled it and knitted socks. Then I sold them for a piece of bread.

When it was winter and the cold was unbearable, we tried to hug each other to keep warm, but there was really nothing we could do. We could not hide anywhere; there was no stove with fire or burning coal; there was nothing to alleviate the cold — nothing, nothing.

It is impossible to imagine because nowadays they show movies that are very cleaned up. Believe me, it was a million times worse; there is no movie or book that can describe what it was like. I guess the people who make movies and documentaries about the Holocaust don’t want to upset people, to show them what really went on. But we know the truth.

Believe me, it was a million times worse; there is no movie or book that can describe what it was like. I guess the people who make movies and documentaries about the Holocaust don’t want to upset people, to show them what really went on. But we know the truth.

We Had Nothing

On January 20, 1945, they took us from Auschwitz on a march, night and day, back and forth. Naturally, the SS and their dogs were with us. During the march, anyone who walked to the edges or to the back got shot; we had to walk in the middle with no proper shoes, no nothing. People were weak and many of them could not make it. You could not rest even if you wanted. You couldn’t. They killed you if you stopped to rest. You did not dare to look around. Once, when the Nazis got tired and we stopped, I was lying down in a barn and the place where I put my hands was full of horse dirt. My hands were full of horse excrement. Somehow, I cleaned them.

Another night we stopped over in a brick factory. Some people threw away a piece of bread and a rag, a kind of a blanket. I tied the rag to my neck and put the bread in there. Aranka had taken off her shoes when we got to the factory and could not put them back on because her feet were so swollen. She told me, “That’s okay, you go ahead, and I will stay.” I said, “Never in my life. What will I say to our father, that I just left you here?” I gave her my bread, lay her on the blanket and then tied it around my neck and dragged her all along, marching and marching....

We walked for three days and nights. Back and forth. My sisters and I were always together. So this is how my sister survived. I don’t know with what strength I was able to pull her and keep marching. How did I do it? It was God’s will. I was so weak, I hadn’t eaten anything except maybe some potato peel or some grass. I was very, very weak. I have no idea how we survived. It was January, winter, and very cold. We did what we had to do to survive – march and march. We did not have shoes, we had rags. Whatever we could put on our feet, we put on. If you were lucky to find one shoe you took it or just covered your feet all around with rags.

There were three women with us: Gyongy, Surika and Szeren. Back and to the side were Aranka and I. We were always next to each other. I called their names the whole time to make sure that we stayed together and kept walking. If you stopped, you were dead. The Nazis killed you immediately or you were left alone to die in the freezing cold.

After the march from Auschwitz we arrived in Bergen-Belsen. Our life there was unbearable. The latrines were outside and if someone fell in it was bad because you could not get out of there. It was very, very dirty, a disgusting place. The food was next to nothing but somehow we survived. Even there I tried my best to survive. Whenever I got my hands on some potato peel, I grabbed it. There was nothing to eat. They did not treat us like human beings. We lived in the barracks, there was nothing to sleep on, not even a piece of wood to lie down on; we slept on the floor. We lay there like sardines in a can, one close to the other, almost one on top of the other. If someone died, we thought, “Oh, there is an emptier place to lie down. Now we will have some extra room.” We were not acting like human beings. During the day we did nothing; they did not make us work. They just kept us there. The SS and the kapos watched over us.

***

I remember the day of liberation very well. One day, I woke up in the morning and it was very quiet. We did not know what was happening. We did not have any way to hear the news — no TV, no radio. Nothing was moving; it was very quiet. I went out of the barracks and did not see any Nazis walking around. So, naturally, I went to look for food. I saw people going somewhere and I followed. I went to a place where they stored things, and there were big barrels of food — sauerkraut and sour pickles. People tried to eat some of it, but they were very tall barrels and hard to reach. I was very hungry, and when I tried to take some food out of the barrels, I almost fell into them. People started eating very quickly because we were all so hungry. Many died quickly because their stomachs could not absorb the food. We saw the Canadian and British soldiers coming into the camp to liberate us. Some of the Nazis had escaped before they came.

It was very exciting and confusing when the British and the Canadian army marched into Bergen-Belsen on April 15, 1945. We were confused until we found out that we were finally free. God bless the British and the Canadians. They saved our lives. The soldiers had been told that if they waited even one more day, they would have nothing to come for because apparently the Germans had poisoned the food and wired the camp with explosives.

I was very skinny, just skin and bones, and very, very weak. We did not have clothes; the Nazis had only occasionally given us rags to wear. I think that all the food and nourishment that I had had back home helped me to survive, helped me stay alive. Some doctors took a picture of me with two husky people. I think that if I saw the picture today, I would recognize myself because my face was probably the same, only skinnier, with no flesh. There are certain things you want to forget. Only my two sisters and I had survived; we were the only survivors in our family.

After the liberation, we stayed in Bergen-Belsen in wooden barracks for approximately a month, and then they moved us into the buildings that the Hungarian soldiers used to live in.

Many years later I went to Bergen-Belsen with my husband and saw the barracks. We made the trip especially, to see the places where my husband and I had spent the war. It was heartbreaking to see the camps, to walk on blood-soaked ground in Auschwitz, where so many people had died, to see the suitcases, shoes, hair and clothing that had been taken away from all the Jews who arrived in the camp. I kept thinking, “How can human beings do these terrible things to each other?” On one of the buildings were the names of the people who had been killed and the cities they came from. At the top of the list, I saw my father’s name, Albert Weisz. Next to this building was the courtyard with the wall where people were lined up and shot in cold blood.

Edith and her husband, Joseph, on their wedding day. Toronto, 1953.

Joe and Edith Kirshen. Toronto, March 2006.

Edith, age ninety-one. Toronto, October 6, 2017.