Denise Fikman-Hans

Born: Paris, France, 1938

Wartime experience: Passing/false identity

Writing partner: Shalika Sivathasan

Denise Fikman was born in Paris, France, in 1938. In 1942, Denise’s father, aunt and uncle were taken from their home and deported to Auschwitz. Denise’s mother sent her six children and two nieces to hide on a farm, but they were soon separated and sent to different families and then to a convent and monastery.

Denise stayed in the convent until 1948 and was then called back to Paris to live with her mother and her new husband. Denise finished her high school studies in France, and in 1956 she joined her cousin in Montreal, where she worked as a secretary. She married her husband, Milan Hans, in 1959, started a family and then moved to Toronto in 1979. Denise has been very active in Jewish community organizations, and after she retired, she became involved in Holocaust education through the March of the Living and the Toronto Holocaust Museum.

Separated from our Father

It was one year after the armistice was signed that the persecution of the Jews in France began in earnest. The first roundup occurred on May 14, 1941, and it was then that my father and Uncle Simre (Aunt Esther’s husband) were taken, along with about 3,700 other Jewish men. The Nazis had set up transit and internment camps at Beaune-la-Rolande and Pithiviers, and later opened others at Drancy and Compiègne — all located within a hundred kilometres of Paris. The week before, on May 9, my father had received a billet vert, green ticket, which told him that he was to report to the police station. It was from there that he was taken, without warning, to Pithiviers. The authorities did not care that my father had a wife and children; he was simply told that he could not go home, and no explanation was given to our family. No one was aware of what was happening outside of France at that time. I have heard that many of the Jews held at the big transit camp in Drancy would joke that they were going to Pitchipoï, an imaginary place. Still, it was clear to my mother that something big was happening as many in the district had similarly disappeared. We would later learn that my uncle Simre had been taken to the camp at Beaune-la-Rolande. While my uncle was sent back because of his issues with sciatica, it was a full six months before my father received his first pass to come home from the camp at Pithiviers.

At the time my father was taken, my mother was already three months pregnant with her sixth child — my youngest sister, Monique. Yet, as a Jewish woman, my mother was prohibited from going to the hospital to receive treatment because of the new laws instated under the Nazi regime. It was under these circumstances that my mother, with the help of her sister Esther and a sage-femme, a midwife, gave birth to Monique in her bedroom. It was November 13, 1941, and although I was only three and a half at the time, this event marks one of the earliest and most vivid memories I have. I still remember the sound of Monique’s cry as we children peeped through a crack in the door.

With the birth of my sister, my father was finally granted permission to leave the camp, but his pass was only for two weeks, and we knew that he would soon be called to return to Pithiviers. So, collecting all six of her children, including the newborn baby, my mother made the journey by train to the Gestapo office in Orléans, where she asked for an extension of his stay. Fortunately, the request was granted, but my mother had to repeat this process several more times. With each pass he got, my father was given a few more weeks to stay with us. Despite all of this uncertainty and upheaval, my parents continued to work in order to put food on the table.

The last time my father was granted such an extension was a day that I remember very clearly. As always, we children had been dressed very nicely and had taken the train down to Orléans. When we arrived at the Gestapo office, the Nazi who was sitting behind the desk that day appeared very nervous and agitated. “Your husband has to go back to the camp,” he said to my mother. “You have had enough passes already.”

My mother pleaded and pleaded with the officer, and he became increasingly nervous, but still he refused. That was when the baby, Monique, started crying. Now, when the baby cried, all of us children began to cry too. My mother became anxious because of all the noise we were making, and she pushed us all outside. Turning back with the baby in her arms, she looked at the German officer and said, “Without my husband, I cannot feed this baby. You will have to take care of her.” And just like that, she placed the baby on his desk and promptly turned to leave.

The officer was so startled that he called her back and signed another extension for my father right away. A few weeks later, when my father received his final notice calling for his return to Pithiviers, he decided not to go back, choosing instead to go into hiding.

It was the winter of 1941, and for several months my father was hidden in what was once a maid’s room on the sixth floor of a building on the rue Greneta, the same building where my aunt Esther lived with her husband, Simre, and two daughters, my cousins Isabelle and Cécile. My father’s room was incredibly small and had no electricity, no washroom and no running water. To be alone in a place like that was very depressing, and so every other day my mother and my sister Isabelle went to visit and bring him something to eat.

Although, as a child, I was aware that something was wrong, I now remember only certain sounds and images. I cannot remember what I thought or felt. I know that my parents were scared that, since I talked so much, I might blab about where our money was, where the rations we had received were and things like that. How any of us children, particularly me, were able to stay quiet all those years is something I have never figured out, especially since, at that time, I really did not understand exactly what was happening or why.

In June 1942, Jews in Paris were required to wear a yellow Star of David. I was later told that when my brother Fernand turned six and was made to put on the star, I called him a “dirty Jew.” I was about four and must have heard the phrase somewhere. I believed, because of the star, that he was a “dirty Jew” and that I was not. This just goes to show how important clothing was at that time, and how dangerous too. Many people who saw Jews wearing the Star of David would simply walk away. Some would smile and be friendly, as if they felt sorry, but most did not want to be associated with us.

Finding Shelter

In France, most of the three quarters of the Jewish population that survived the war, and especially the children, did so because they were hidden. There were two organizations in Paris at the time that took care of children: Union générale des israélites de France (UGIF; General Union of the Jews of France) and Œuvre de secours aux enfants (OSE; Children’s Relief Agency). My mother did not have confidence in the UGIF because, at the time, it was overseen by the Vichy collaborationist regime. The OSE was more clandestine. It had more volunteers, was better organized and had a big réseau, network, to assist the children. It was through the OSE that we were able to find our first hiding place.

We eight were to be sent to a farm in a village called Quatre-Routes, located several hundred kilometres south of Paris My two brothers went first, and my cousin Cécile and les trois petites, the three little ones — Mireille, Monique and I — followed not long after. I am sure that my mother must have given us something to eat on the journey, but what I remember most from this time was the feeling of abandonment as she dropped us off at the train station and walked away.

The farm belonged to a Christian woman whom we called by the derogatory term la mère bâillon, which loosely means “mother shut-your-mouth,” and throughout those months with her, we were all very unhappy. My brother Maurice, who was nine at the time, once told me that he had said something to la mère bâillon one day, after which she slapped his face hard and told him he was a un sale juif, a dirty Jew. This was the woman who was meant to take care of us. I remember as well that when Mireille, only three years old at the time, did not know how to put her skirt buttons into the buttonholes, la mère bâillon left her outside for half the night as punishment. She beat Fernand, who was just eight, almost every day for wetting the bed.

Looking back, I know that non-Jews who hid Jews did help to save us, often at very high risk to themselves. While some were nice and did so out of the goodness of their hearts, others, like la mère bâillon, were very mean and did it more for the money — for greed. The OSE paid non-Jews to hide Jewish children, and my mother paid the farm owner as well. To la mère bâillon, we were a source of cheap labour, and she would get all of our rations for bread, clothing and the like. Once a week, on Mondays, la mère bâillon gave us each a loaf of bread, which was meant to last us the whole week. My brother Maurice would always eat his all at once, making himself sick. We small ones couldn’t do it, and the bread would go back in the cupboards where the rats would eat it, so we were very hungry all the time.

One day, my mother, who missed her baby very much, sent our neighbour Madame Janin to bring Cécile and Monique back to Paris for a visit. La mère bâillon tried to bribe Madame Janin not to take the girls by offering her some chickens, but Madame Janin simply took the chickens and left with Cécile and Monique in tow. I don’t know where they met that afternoon, but my mother would later recount that as she was giving the girls some cookies and milk, some of the crumbs fell onto the ground and Monique, having been hungry for so long, went down onto her stomach and licked up every crumb. How horrible it must have been for her to see her baby like that. My mother was shocked when Cécile told her how hungry and unhappy we all were.

***

By September we were sent off again on the train…. Monique and I were taken quite far from the others. We were chosen by a woman named Madame Grosbois who, along with her husband and two children, lived in the village of Chazé-Henry. The family was nice to us but very taciturn, very stern. I cannot remember any laughter in that house. They were sombre and did not talk to us much. I remember, though, that their sixteen-year-old daughter had a skin disease called la gale, scabies, that was very itchy, and because I used to bite my nails, I was elected “Scratcher Number One” and had to scratch her legs every day.

***

The eight of us had been in our various placements for a few months when each of our guardians, afraid that they would be caught hiding Jews, wrote to my mother asking permission to have us baptized. To them, it would be proof that we weren’t Jewish.

“As long as it will keep them alive,” my mother responded, “you can do what you like.” And so, in May 1944, each of us children was baptized. I still remember the day very well: The priest put water on my forehead and salt on my tongue. But mostly I remember Monique and the way that she screamed when they gave her the salt. She was just a baby after all.

I remember being with our guardian’s daughter in the village one day when the Americans rolled in with their big tanks. I knew that they were American because, as they were passing through, they handed each of us some Wrigley’s chewing gum. Everyone in the village was so happy. They felt such relief that the Americans were there — for them, it was like liberation, even though the war would not end until May 1945, almost a full year later. In any case, for the Germans, the number one goal was always the annihilation of the Jews. So while American and British soldiers were liberating village after village, the war itself was very much still on.

I don’t remember the circumstances now, but it was approximately around this time that all eight of us children were suddenly returned to Paris. Once again, my mother had to find us another place to hide. Eventually, she found one with Les Soeurs de Notre-Dame de Sion. This order of nuns had two big expensive boarding schools, one in Grand Bourg, Paris, and another farther north near Belgium in a place called Saint-Omer. While my two brothers were sent with monks to a school for boys, the six girls were sent first to the school in Paris, and later, toward the end of 1944, to the convent in Saint-Omer. We stayed there for the next four years.

The nuns at the convent in Saint-Omer were all teachers or professors, and they were some of the most educated people I have ever known. And yet, while the nuns provided us with food to eat and a place to sleep, they did not want us to go to the school attached to the convent since we did not have the means to pay. Instead, we were sent to the local school in the village. This was the first time I had gone to school in almost two years, and I received an excellent education there. Aside from a few people in the convent, very few in the village knew that we were Jewish….

At the convent, the nuns were severe and could sometimes be very mean. Once, they beat me because I talked during lunch, and they often came to see where our hands were during the night; even when it was cold, we were not allowed to put our hands between our legs.

***

From our years at the convent, we were taught to be extremely polite and well behaved. In the end, I really did love the convent. I became very familiar with the Bible — the Old and New Testaments — and I was fascinated by the stories of Moses and Joseph. I loved the pageantry and the music of the holidays. And I remember the joy at Christmas when we went to midnight mass, the church decorated with the baby Jesus. I even had my First Communion at the convent when I was seven years old, and I still remember how proud I was walking into the church that day. I really loved the Catholic religion and was a practicing Catholic, but I did sometimes question the Church’s teachings. I was a precocious child, and I remember once being punished for saying there was no such thing as a Virgin Mary, that it was impossible for a virgin to have a baby.

My mother came to visit us at the convent twice. I recall these as strange times because when she would arrive at the convent, all the orphaned children would surround her and call her Mother as well. I felt as if she were not even mine.

My mother came to visit us at the convent twice. I recall these as strange times because when she would arrive at the convent, all the orphaned children would surround her and call her Mother as well. I felt as if she were not even mine.

Uprooted

Every day, my mother went to the Hôtel Lutetia, where they kept lists of all the survivors, to see if her husband, brother or sister had made it home. She would later learn that all of her family in Poland — her mother, her brother Yankel and her sister Fraïné’s whole family — along with twenty-one members of the Fikman extended family (including eleven children) had all perished under the Nazi regime. She was truly all alone.

In 1947, my mother brought her two sons home, but les trois petites, which included me, had to stay at the convent for another year. Then, one day in the early fall of 1948, the Mother Superior called us three girls in to see her. “You are going home,” she said. Then, without any explanation, she stated, “You have a new father.” Just like that. A new father? What happened to my father? What’s going on? I was ten and a half years old, and I felt the same way that I had felt almost six years earlier — wondering what my father could have done so wrong to be taken away from us like that. Without saying a word, my sisters and I returned to our rooms to gather the few things we had (souvenir cards and other small possessions), but other than those, we left with what we wore on our backs. Despite their good hearts, the nuns did not give us a change of clothes, not even a pair of socks. Later, I found out that they had not wanted us to leave. The nuns believed that once you were baptized, you belonged to the church. My mother had to fight to get us back, and the sisters were angry, but eventually they agreed to let us go.

We three travelled back to Paris by train on our own. I remember feeling so much trepidation and grief on that journey. I had loved the convent, and I was sad to be leaving. I had been at the convent for four years, so I was leaving all that I knew and going toward something completely unknown. I had so many questions: What were we going to find when we got to Paris? Who was our new father? What was happening?

My trepidation, apprehension and sadness only increased when we finally arrived. Seeing my mother again, there was no happiness. I realized then, for the first time, that I had not only lost my father in the war but my mother too. We had been apart for six years; it was such a long separation, especially for such a young child. Much as I tried, I was never really able to reconnect with her again. It was extremely hard for me. Although my mother was a hero to me — I put her on a pedestal — she felt so detached, as if I had no emotional connection with her whatsoever. I came to feel that my mother was preoccupied all the time, that she had no time for us children. Now, however, I understand just how extremely difficult the times were for her. She was simply doing what she needed to do for all of us to survive.

When I returned to Paris, I also learned that what the Mother Superior had said was true. My mother had gotten remarried to Monsieur Brenner, a man she had met six years earlier when he and his family were on their way to the police station. Monsieur Brenner had, by that time, suffered a great deal, losing his wife and all three children in Auschwitz. I can still remember the number tattooed on his arm: 57113. He never answered our questions about his time in the camps. He was a very taciturn man. While my older siblings decided to call my stepfather Monsieur Brenner, les trois petites, we three tender little girls, wanted him to feel better after all that he had lost and called him Papa. However, because I was in the middle, whenever I addressed the older siblings, I called him Monsieur, and when I talked to my younger sisters, I called him Papa. I was all mixed up, and I remember the atmosphere in the house at that time as awkward. I don’t remember anything being happy at all.

Monsieur Brenner was always nice to us, but he was a cold man and basically a stranger. Even my older siblings and cousins had become strangers to me since we, too, had been separated for many years. In some ways, it was much easier for Mireille and Monique to adapt — they were too young to have any recollection of the years before the war. I was just old enough to remember earlier times, and so the experience was really quite traumatic. I felt completely lost and uprooted. I felt as if I did not belong anywhere — not back at the convent and not with my family either. From that moment on, I was a very sad child.

The first Sunday morning after we returned to Paris, I snuck away to the nearest church so that I could attend mass. I was still completely immersed in the life of the convent, and at the time, I believed it was a mortal sin not to go to mass. It wasn’t long afterward that my stepfather told us to bring him all that we had brought home from the convent. We had not been allowed to take much, but I had brought with me some beautiful religious pictures, including images of Jesus with a flaming heart and the Virgin Mary. The pictures were on a kind of parchment, and when you held them up to the light, you could see another picture behind. I really loved those images. So, when my sisters and I brought them to my stepfather in the living room, I watched in shock as he tore everything into small pieces and threw them into the garbage. “From now on, you will learn that you are Jewish,” he said. “You will forget all about the convent.”

Much later, I learned it had been Monsieur Brenner who had first insisted to my mother that we come home from the convent, telling her, “Not one Jewish child should be in a convent.” It was important to my stepfather that we learn the Jewish bible and history, since he had gone to Jewish school from the time he was three years old, and knew everything by heart. For us to stay in a convent when so many had been killed for being Jewish seemed to him like an insult to all the Jewish victims.

***

My parents often quarrelled, and I remember feeling angry at my stepfather for making my mother cry. In fact, my brother Fernand and I believed that our father would come back. Fernand said that since Monsieur Brenner had survived the camps and was not as outgoing or streetwise as Father, then surely our father would come home as well. Sometimes, when I was on the bus or the subway, when someone would look at me directly, I would say to myself, Oh, maybe it’s my father. This was a recurring sad undercurrent of my life. After the war, we did not have any grief counselling or a chance to talk about our feelings. All we could do was keep everything inside.

Denise and Milan on their wedding day. Left to right: Denise’s mother, Perla; Denise; Milan; and Denise’s stepfather, Urka. Montreal, August 23, 1959.

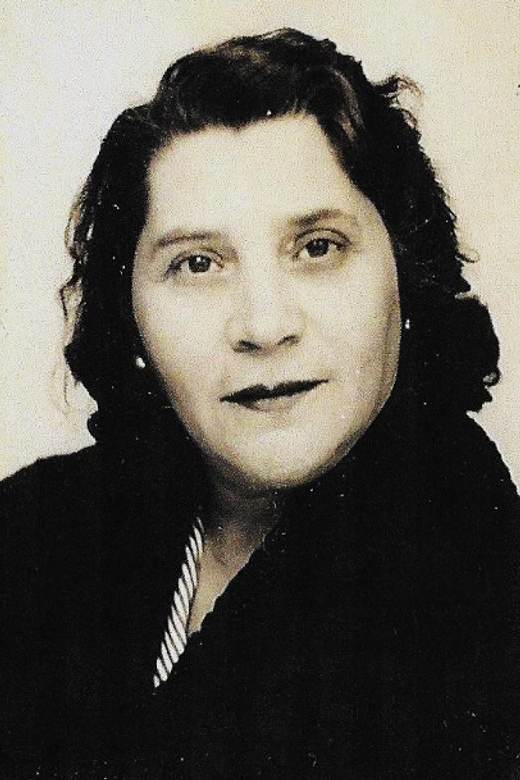

Denise’s mother, Perla Jurkiewicz, and stepfather, Urka Brenner. Circa 1956.

Denise, right, with her Sustaining Memories writing partner, Shalika Sivathasan. Toronto, 2017.