Dan Brown

Born: Lodz, Poland, 1930

Wartime experience: Ghetto, camps, forced labour

Writing partner: Farla Klaiman

Dan Brown (Szurek) was born in Lodz, Poland, in 1930. In February 1940, Dan, his parents and his sister were forced to move into the Lodz ghetto, where they lived for four years.

When the ghetto was liquidated in August 1944, Dan and his family were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. After three days in Auschwitz, they were sent to Stutthof and then to Dresden to work in a munitions factory. Dan’s mother and sister died in Dresden. In April 1945, Dan and his father were forced on a death march to Theresienstadt. They remained there until their liberation in May 1945; shortly afterward, Dan’s father died of typhoid fever. As an orphan, Dan was sent to England as one of the Windermere Children in 1945. In 1948, he arrived in Canada and settled in Guelph, where he lived with the Browns, his adoptive family. Dan married, raised a family and became a successful business owner.

My Family

I was born on March 10, 1930. My early years in Lodz, Poland, were filled with wonderful memories of my family. My parents were both born in Lodz. My father, Pinches Zelik Szurek (also known as Zeltek and Zelig), was born in 1896, and my mother, Anja Kni (or Anna and Chana), in 1898. She was a kind, beautiful woman. My sister, Ella (Rachel), was a few years older than me. She too was beautiful and vivacious. My father was a kind, unassuming man, a happy person who enjoyed sharing his good fortune with others.

We lived in apartment number 5 at 18 Piotrkowska Street. It was a spacious main-floor suite. Our building had a large courtyard at the back, with a semicircular driveway where the driver of a horse and carriage could pick us up and take us to our destination. We had a Polish housekeeper who lived with us for many years, and a Polish cook. I was fortunate to have had a privileged childhood.

Our family was not religiously observant, and I remember that my grandfather Izaak didn’t have a beard, as most religious Jewish men had at that time. This could have been because he did not want to bring attention to himself as a Jew. I now understand that antisemitism was always present.

I recall an incident just after the war started when the Germans came to our apartment and forced my father to open his floor safe. They emptied the safe, throwing papers on the floor and all over the room as they searched for jewellery and other valuables. This was very upsetting for me to watch.

I attended a private school with Jewish and Polish students before the war. I had always wanted to be an electrical engineer, and my favourite subject was math. One day, I had a terrible incident at school. I was in the washroom and a non-Jewish boy pushed my head against the wall. This was a painful and humiliating experience for me. From a young age, I had been taught by my parents not to bring attention to myself when away from home, so I never reported the incident to my teachers.

The Lodz Ghetto

After the Lodz ghetto was established in February 1940, the city’s Jews received an order to leave their homes and move into Bałuty, a poor section of Lodz where the ghetto was located. At a young age, my life began to spiral downwards. I was ten years old when my family and I were forced to move.

The availability of bread and groceries was very limited in the ghetto. At first, our former housekeeper would bring us bread. After a short time, the guards would not allow her to come into the ghetto; she then would hand the bread to us through openings in the fence. As time went on, it became too dangerous for her to continue this kind deed.

I remember that everyone was hungry in the ghetto. The outside of the ghetto fence was surrounded by guards with rifles. There were some apple trees with branches that hung over the fence. One day, I embarked on a dangerous mission. In broad daylight, I climbed the fence and shook the trees to make the apples fall inside the ghetto. The guards started shooting to scare me off, but more importantly we had apples to eat. Thinking back, I didn’t give much thought to the potential consequences of the risk I was taking. I have always been determined and shamefully stubborn — no doubt these characteristics helped me to survive.

We remained in the Lodz ghetto until the Germans evacuated it in August 1944. They deported almost all of the remaining residents, including my entire family, to Auschwitz-Birkenau by cattle car. The conditions were horrific; the elderly, the young and the sick were crammed into filthy cattle cars. The stench was unbearable, and breathing was difficult. We were treated like cattle! Hearing the cries of the helpless, frightened people was heartbreaking. Fear was ever present.

I have done my best to remember all the heart wrenching, horrific details of my experiences. I want my descriptions to be accurate in memory of those who perished, for the innocents who were murdered.

Dresden and the Death March

Dresden was a centre for arts and culture. It was also a production centre with factories for motor cars, medical equipment and cigarettes, among other goods. Our group was put to work in a munitions factory that was housed in a former cigarette factory. My job involved placing two-inch iron cubes in a vise and filing them to make them smooth. A foreman would check my work to make sure I was doing a good job. I was never able to get them perfect. I have no idea what these cubes were used for.

My friends in the factory began to disappear one by one; most likely they died because of abuse or illness. While working in the factory, my mother became seriously ill and died shortly before the bombing of Dresden.

Between February 13 and 15, 1945, Dresden was firebombed by the United States and Great Britain. The city centre was destroyed and approximately twenty-five thousand people were killed. I will never forget walking on the outskirts of Dresden at night and seeing the city in flames from the firebombing. The noise, the fire and the loss of lives were staggering. It was a nightmare, and I was very frightened.

My sister, Ella, was killed when the factory we had been working in was bombed. I later learned that she was buried in Johannisfriedhof, a cemetery in Dresden. The loss of both my mother and my sister was a tragedy for me. I was heartbroken.

Following the bombing, our group was relocated to a nearby camp. Later, from April 11 to 23, 1945, those who were left from our group were sent on a death march. For twelve days, we were forcibly marched on foot from Dresden to the Theresienstadt (Terezín) ghetto and concentration camp in Czechoslovakia. I was still with my father, my uncle and his family, but men and women were separated on this death march. We walked about ten hours a day, covering roughly ninety kilometres. It was very cold, and we slept in forests, barns and once in a stadium without a roof. I remember deliberately choosing to walk in the eighth row from the front so as not to be conspicuous to the guards. Those who no longer had the strength to keep up with the group would fall behind, near the back. They were shot by the monstrous German soldiers who guarded us. Being no longer useful, the weak and the sick were cruelly disposed of. I can still hear the shots. I can still hear the screams.

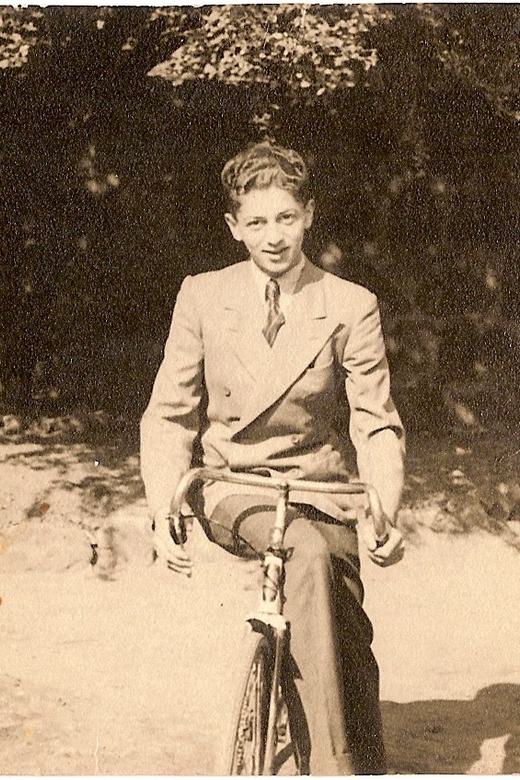

Dan Szurek (Brown). Glasgow, Scotland, September 1946.

Dan and Fran on their wedding day. Toronto, Ontario, July 1960.