Benny Freedman was born in Lodz, Poland, in 1924. One of eight children, he came from an Orthodox home where his father was a butcher and his mother taught Yiddish.

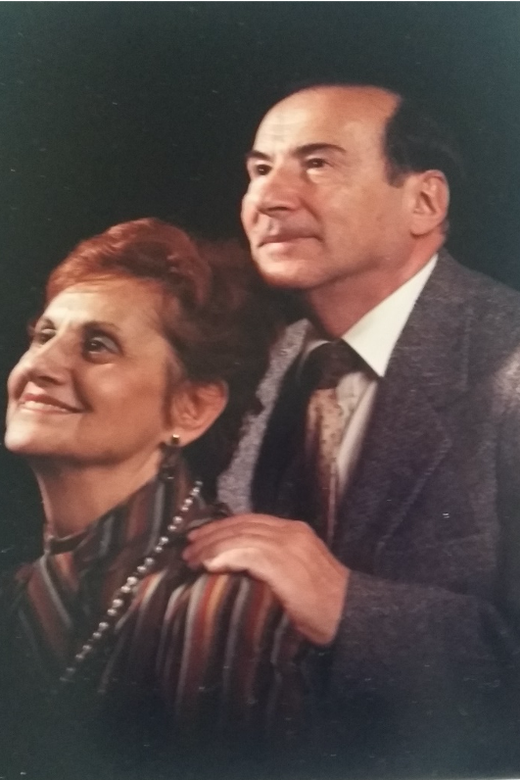

After Germany invaded Poland, Benny and his family moved from Lodz to Ostrowiec and then to Staszów. Benny was eventually sent to the Skarżysko-Kamienna forced labour camp, where he worked in a munitions factory. When the camp was liquidated in the summer of 1944, he was evacuated to the Buchenwald concentration camp and then sent to the subcamps of Schlieben and Ohrdruf. In March 1945, Benny was forced on a death march, and in April he was liberated by the American army. Benny was the only member of his family to survive the war. After spending time in a displaced persons camp in Ainring, Germany, he lived in the Netherlands, where he worked as a tailor. Benny immigrated to Canada in August 1948 with the help of a Swedish Jewish organization and became a Canadian citizen in 1954. He worked in a sportswear factory in Toronto, where he met Denise, and they married in 1974. Benny Freedman passed away in 2024.

The Light in the Room

I was born on December 22, 1924, in Lodz, the second largest city in Poland. Lodz was a city full of textile factories. Anyone who needed a job could get one.

My father’s name was Paltiel and my mother’s name was Freindela Leah. They had a traditional Orthodox Jewish home. My mother was an eishes chayil, a righteous woman. She taught Yiddish to young girls. I loved my mother so much. We had a special relationship. I had four sisters and three brothers; the youngest two were twins. I was the eldest son. When I was born, my father said there was light in all the rooms. One sister died before the war. The others all perished in the war. Only I survived.

Finding a Way to Survive

Skarżysko-Kamienna was a forced labour camp. I was part of the first one hundred Jews to be sent there to work in an ammunition factory. I was given a number — fifty-one. The building we lived in was called Economica. The Germans called the camp HASAG, which was the name of the company we worked for. A German engineer taught me how to operate a huge machine that looked like a sewing machine. It produced igniters for grenades. He taught me how to work it, watched me for a few minutes and said to me, “Du Bist ein tapferer Junge.” (You are a brave youngster). He was not a bad person. I worked on that machine for two years.

Every Friday, we got an envelope with our pay and a note indicating how many hours we had worked, just like the Poles who worked there. In the beginning, a wagon filled with bread would come to the camp from Skarżysko. We used our money to buy food.

After a few months, the SS came and took over control of the camp. They made us give them any money we had, as well as any rings or jewellery. That’s when the tragedy started. Until then, we’d had money and bread. Now we didn’t live in the Economica anymore. We lived in the barracks in the forced labour camp. I remember in 1942, on Erev Yom Kippur, the eve of Yom Kippur, the Ukrainian SS made an Appell, a roll call. We all had to stand in line, and one Ukrainian SS man looked over everyone and then chose five people. He took them to the back, to the garbage dump, and shot them. This was our introduction to the SS.

As prisoners in the camp, we had very little to eat. Ten people shared a loaf of bread made from potatoes. If we squeezed the loaf, water came out. We also had two soups a day, one was a type of broth that was mostly water and the other was a more filling soup.

Some prisoners had money and others knew Polish gentiles from their hometowns, who also worked in the factory and brought them bread or buns or other things for money. But I didn’t know anybody. I had to figure out a way to get extra soup or an extra piece of bread. When the Jewish foreman finished giving out tickets for soup, he threw them away and I would pick some of them up because I knew that a few months later he would use the same tickets.

My mind was always working. I took a metal sheet from the factory, put four bricks on it and wood underneath it, and made a fire so a woman could cook potatoes or a pigeon. I was given a little money for that. And when I had enough, I would buy a loaf of bread. I tried to find any way to keep myself alive. And I always had a razor in my pocket, to be clean and presentable.

When we had a few minutes to rest, we would talk about what we would do when we were free. One woman said she would sleep a whole month. Another woman said she would eat a whole loaf of bread. When I was asked what I would do, I said I would travel. I would not get married. I saw this world as barbaric.

One day in 1942, a Pole who was working there came over to me and said to me in Polish, “You know, Benny, they are gassing Jews in Treblinka.” I said, “It’s impossible. A country that produced Heine and so many philosophers and Mozart? Beethoven? It’s impossible.” I couldn’t believe it. But it was true. I knew then that my family would probably be killed.

I am a survivor of a group of five who supported each other, trying not to lose hope.

The Death March

After the war, while I was still in Germany, I wrote about my experience during the death march from Buchenwald. I wrote it in Yiddish. This is the translation:

The sky is covered with black clouds and a thick rain is pouring over the unfortunate remaining inmates on the last death march of the Buchenwald concentration camp. Nature feels our pain. We are living skeletons that according to the laws of nature should not be able to move. The memory of our 1,500 murdered friends, their voices ringing in our ears, pushes us forward. We must live in order that there be thousands of witnesses to testify that the world let people carry out such barbarism. We justifiably condemn it on behalf of our dead fathers, whom the world can never resurrect, and on behalf of our dead brothers and sisters.

We continue to march over the wide roads and beautiful landscapes, but our thoughts are not focused on the present. We are getting shot from the back, by the sadistic murderers that took away so many of us. We continue to march forward without any destination, over woods and fields with mass graveyards under us.

I am a survivor of a group of five who supported each other, trying not to lose hope. I give hope to my friend who wants to sit down to end his pain that only grows stronger and stronger. Everyone wishes to die a natural death on a little hay and not from a murderer’s bullet. As I continue to march forward, my mind recalls different childhood memories. I am so far away from home. Who knows how far? Suddenly, I get hit with a club from one of them. I forget about everything and only hear the wild screaming from them, “Why can’t you run faster? Do you want to stay here?” I quickly run back into the rows and I still have hope. I don’t think about what’s going to happen next. Suddenly, I hear a shot. Everyone knows that someone else has become a korban, a sacrifice, in the thick woods. A strong wind starts to blow over the heads of our pale faces, as if to say that the end of our pain is very close. The rain pours over our naked bodies, making us weak from thinking about what the next few moments will bring us and how many sacrifices we will give.

We continue to march forward under the careful scrutiny of the infamous SS, people who want to erase us as quickly as possible.

The wind blows from all sides, bringing along with it all kinds of noises from cannons and bombs that tell us that our liberators, and thus freedom from our murderers, are close. There is a deathly silence among the marchers. I see that some people are talking quietly about politics and I feel that something is going to happen. But our fantasies are shattered by the wild shrieks of our guards. As we continue to march past trees and woods, we start to feel that we will live and we will be able to enjoy nature. We will have rights like everyone else to enjoy. Until now, the only thing that we did was nourish the earth with the blood of our nation. Why do we have to suffer, I ask. But who should I ask? Who can answer me?

Everything is quiet. We can hear only the screams of those who fell and are going up to the heavens to pray for all of us that we should be saved from hunger and cold. We are exhausted from waiting for the three potatoes that we get in the evening. At night, we hear the shooting of those who tried to save themselves by escaping in the last days.

It’s already 11:00 a.m. We start marching much later today than on other days. We run faster than every other day, too, on the very narrow paths, deep in the woods, like we are trying to avoid danger. We just sacrificed the last korban, who wanted to save himself minutes before freedom.

We discover that we are getting closer to a concentration camp in the middle of the woods that will end our plight. We arrive there. We stand in a place deep in the woods where there are barracks and a watchtower that looks like the chimney of the gas chambers.

We get an order to line up, five in a row, and we get counted. A kind old watchman speaks to us with warm words. It is the first time we have heard such words since the beginning of the war. I am shocked to see a bed and an oven in the middle of my room. I immediately lie down on the bed with another friend and we get a piece of bread and warm soup.

Night is falling and with it a lot of grief and sadness from the past. We hear the heaving of the half-dead skeletons who are frightened of this night more than all the time on the march. I lie in bed with the same wonder: how did I come this whole way? I am scared to remove my soiled clothing. Maybe the murderers will come and tell us to continue onward. I fall asleep in fear and only while sleeping am I free of my fears. I am awakened by an old German woman offering me some bread and coffee. I look around in utter shock. I can’t say a word. What happened? Where am I? Is this a dream or is this real? We are the same inmates who just yesterday were fighting death, and now we are free. But still we are not free. At that moment, an old watchman comes in and says, “Comrades! The Americans are not far from here. Do not be scared.” I don’t trust these people. I want to scream, “No, it’s not true!” But I just lie in bed quietly. But I wonder what the morning will bring. Is it true that this is the end of all our pain? The sun starts to shine its rays through the closed windows. Does it mean the sun will yet shine for us?

Evening comes. A quiet descends upon us. From the corner of the room I hear a prayer. Gone are the wild screams. There is no fear any longer. Now is the time for revenge. Not by us, walking skin and bones. We won’t take revenge. The door opens and a civilian man comes in holding a gun. He cries out, “Yidden, you are free!” Behind him stand soldiers from the American army who have liberated us. How great is the joy for all the people who have lived to finally reach this moment. A shudder goes through my skinny body. Now that I am free, where are all my sisters and brothers? My father and mother? Zaidy and Bubby? And so many, many more of my family? Now I alone am left.

Thoughts on Liberation

Early one morning, on a beautiful, sunny day, the American army arrived. I remember seeing Black soldiers, who cried to look at us. They looked in their pockets to give us things — chewing gum, cigarettes, chocolate. Among them was a Jewish soldier who couldn’t speak Yiddish. He said, “Ich Moshe.” (I’m Moshe.) That night we made a bonfire with him and tried to explain to him what our lives had been like for the past few years.

Then, both doctors and nurses came to clean us up and check us out. Some people went to the hospital. They checked me and said I was okay. My lungs and heart were okay, but I was just skin and bones. I spoke to God that day. I said, “We are supposed to be the Chosen People. Chosen for what? Destroying the First Temple? The Second Temple in Jerusalem? The Spanish Inquisition? Pogroms? Crusades? Now gassing? What else do you have for us? Now maybe you will leave us alone. Take the Germans and the Ukrainians for your Chosen People. Leave us alone.”

From that time on, I didn’t go to synagogue anymore. I don’t believe a God existed for the Jews. So many gods, and only the Jews must suffer? I decided I was not going to get married. I didn’t want to bring up a new generation in this barbaric world. I kept that second promise.