Seeing History: A Reflection on In the Hour of Fate and Danger by Ferenc Andai

As the child of a Holocaust survivor, John Lorinc has tried to research a wartime experience his father couldn’t share. Ferenc Andai’s eye-witness memoir of the very same episode provided many answers, and sheds light on a dark period in Hungary’s treatment of its Jewish population.

When we were children, my sister and I used to send letters to our grandmother in Budapest, Hungary — my father’s mother, whose name was Klara. My parents fled Budapest during the October 1956 Hungarian Revolution, fearing an antisemitic backlash among the populist rebels. My mother’s mother and her teenage son Adam, my uncle, left a short time later and settled in Montreal. Both grandmothers were war widows in their fifties, but they chose different paths.

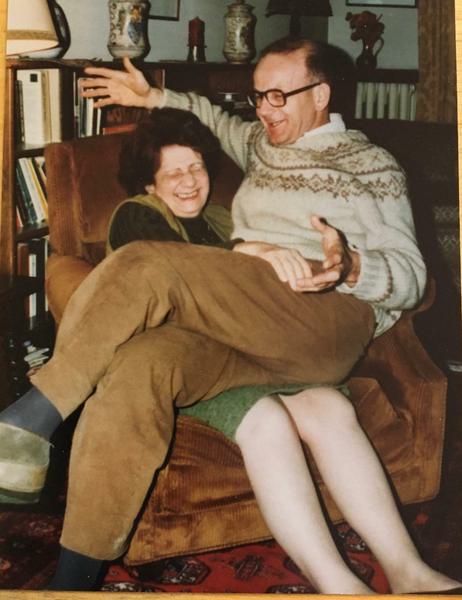

Klara — we called her “the Budapest Grandma” — stayed in Hungary and eventually remarried. She visited Toronto a few times. I remember her as sweet and grandmotherly: she made kuglóf and could play the piano. I have an old photo of her and my father horsing around during one visit — she’s sitting in his deep corduroy armchair in the living room and he’s perched on her lap. They’re both laughing, but the truth is that they had a difficult relationship. When he and my mother fled Hungary, he didn’t tell her he was leaving.

Dr. John Lorinc with his mother, Klara Bardos. Toronto, circa 1973.

Besides those visits, our connection with Klara primarily took the form of a pen-pal correspondence. She sent us letters written on those thin blue “air mail” envelopes, each one covered with Hungary’s lavishly illustrated postage stamps for our collections, and we’d write back with our news. I don’t recall the substance of those exchanges, but I always remembered her address: 17C Radnóti Miklós utca, a five-storey apartment block on the Pest side of the city.

In that photo of my father and grandmother, the bookshelf behind my father’s chair contains a small stack of paperbacks about Tito, the leader of the Yugoslav Partisans during the war and later president of Yugoslavia. They were filled with grainy images of his time as a guerilla. I knew Tito had helped free my father, who was deported in 1943 or 1944 to a forced labour camp south-east of Belgrade called Bor. He didn’t talk much about Bor before he died in 1975, when I was twelve. My mother later told me about his nightmares of being tortured, but I didn’t connect the name of Klara’s street with those books on Tito until much later.

In the bloody pantheon of Nazi concentration camps, Bor doesn’t figure especially prominently. It wasn’t a death camp, although the prisoners — forced to labour in treacherous copper mines in the mountains of Serbia — were routinely worked to death. Bor is referenced in historian Randolph Braham’s scholarship of the Holocaust in Hungary— several volumes, which include an account of the deportations of Hungarian Jews to forced labour camps in the Ukraine and the Balkans. I found over the years a few other scholarly papers, which describe, among other details, the evacuation of the camp in the fall of 1944. The Nazi camp commanders divided the inmates into two groups for death marches to Germany. Many inmates in the first set were murdered soon after departing; the second, however, was ambushed by Tito’s Partisans, who invited the now-liberated prisoners, my father among them, to take up arms and join them in their guerilla war against the retreating German army.

Bor’s best known inmate was a Hungarian-Jewish poet named Miklós Radnóti, who figures prominently in Ferenc Andai’s Holocaust memoir about forced labour in Bor, In the Hour of Fate and Danger. Andai left Hungary with his wife in 1956 and settled in Quebec, where he became a history teacher. He first published the book in Hungarian in 2003. It was translated into English in 2017 and released last year by the Azrieli Foundation, as part of its Holocaust Survivor Memoirs Program.

Andai’s book begins with his journey, by train, to Bor. He describes how he spotted a self-possessed man “with striking features and a friendly smile” holding forth on the cattle car full of deportees as they travelled through the craggy terrain of northern Yugoslavia. The man, in Andai’s telling, seeks to assuage the anxieties of his fellow inmates, who encircle him as he talks. “I watch as he twirls his pipe and rubs it with his fingers, all the while talking without pause.” Another prisoner whispers to Andai that he’s the famous poet Miklós Radnóti.

The grim routines of camp life — which Andai renders in vivid detail, clearly with the intent of bearing witness — include the predictably inadequate rations, the heavy slave work, and the interminable marching between the mine site and the Lagers, camps, scattered in the forested hills surrounding Bor. He describes a form of torture for which Bor was well known — hanging prisoners from their wrists, their arms torqued painfully behind their backs. This was the punishment that haunted my father’s dreams throughout his life.

One inmate, an artist named Albin Csillag, surreptitiously drew caricatures of one notoriously sadistic guard, a Hungarian name Marányi. “He was hoping to get the drawings to Hungary through a clandestine channel, but someone snitched on him and the drawings ended up in Marányi’s hands,” Andai writes. “From that time on, Csillag has been trussed up twice a day and beaten half to death…. At the end, Csillag is thrown into the potato pit to join the twenty-two other prisoners who have been languishing there for weeks. Marányi is a sadistic and fanatical antisemite who incites his officers and guards to commit atrocities.”

As the summer of 1944 turned to fall, and the health of many of the slave labourers deteriorates, Andai writes that rumours about the progress of the war had begun to circulate — clashes between the Serbian Chetniks and Tito’s Partisans, the steady advance of the Red Army, the Nazis’ rapidly evolving plans for retreat, which accompany a general breakdown of the work routines. “The Germans don’t make us work anymore; they have stopped punishing the slaves. A strange, indescribable, depressing mood takes hold of us, the likes of which we have not experienced before. Perhaps it’s how condemned men feel before their execution.”

At this point, the inmates were divided into two groups. Some, in their desperation, attempt to bribe the guards to be allowed to leave with the first contingent. Radnóti, in rapidly declining health, was among them. He hastily copied some the poems he’d composed in Bor into a notebook and left it with one of the prisoners assigned to the second group. They were marched off on the eve of Rosh Hashanah. Andai recalls watching them depart behind stolen carts laden with the possessions of the officers and guards. “That,” he writes, “was the last time I saw Miklós.” The Budapest street where my father’s family lived was renamed after the war in his memory.

Most of the members of that first group died. Some perished from starvation but over a thousand of them were murdered en route. Those in this group who managed to survive the march ended up in Nazi concentration camps.

Andai and my father were assigned to the second batch, which left some weeks later — “a raggedy caravan of more than two thousand men.” After a few days of marching and starving, Andai describes the moment of liberation: rounding a bend, they saw a Partisan soldier high up on a hill above the road. He was armed, and shouted down at the guards to drop their weapons. More Partisans appeared. The guards surrendered, and Andai describes how they are suddenly confronted with the possibility of lynching their captors. Instead, the inmates seized their weapons, herded up the guards and followed the Partisan soldiers to Tito’s encampment — a clearing in a valley bordered by looming cliffs, with hastily erected huts dotting the meadow.

The scene that ensues may be the most striking moment of his memoir. Some two thousand newly liberated inmates sat on the grass, eating their rations, as they listened to a Partisan commander make his case. They were free to leave, this man said, but anyone who opted to remain with Tito’s forces could do so.

“Those who want to join the Partisans raise your hands,” the man declared.

“The throng of two thousand is shrouded in deep silence,” Andai writes. “We look around, casting a furtive glance to the left and the right to see whose hands are raised….When not even a blade of grass moves, the men who are fixed to the ground, paralyzed, begin to stir. The first hand shoots up in the air, and then, as if that were a signal… more hands are raised.”

The specificity of Andai’s memoir is his gift to the historical record — an act of documenting for posterity what he saw and experienced, and the furthering of our collective understanding of a genocide that is rapidly receding beyond living memory.

But for me, the opportunity to “see” this history through Andai’s eyes is even more poignant, because he has enabled me to witness a turning point moment in my father’s life, one he was never able to share.

After all, my father’s hand went up that fall day, on that meadow somewhere in the mountains in northern Serbia — a gesture that determined his fate (and possibly survival) for the balance of the war, and also explained the presence of those paperback biographies that sat in a strange little pile on the bookshelf behind his armchair in our North Toronto home.

John Lorinc is a Toronto journalist and editor who writes about urban affairs, business and technology for various media. He is also the Toronto non-fiction editor at Coach House Books.