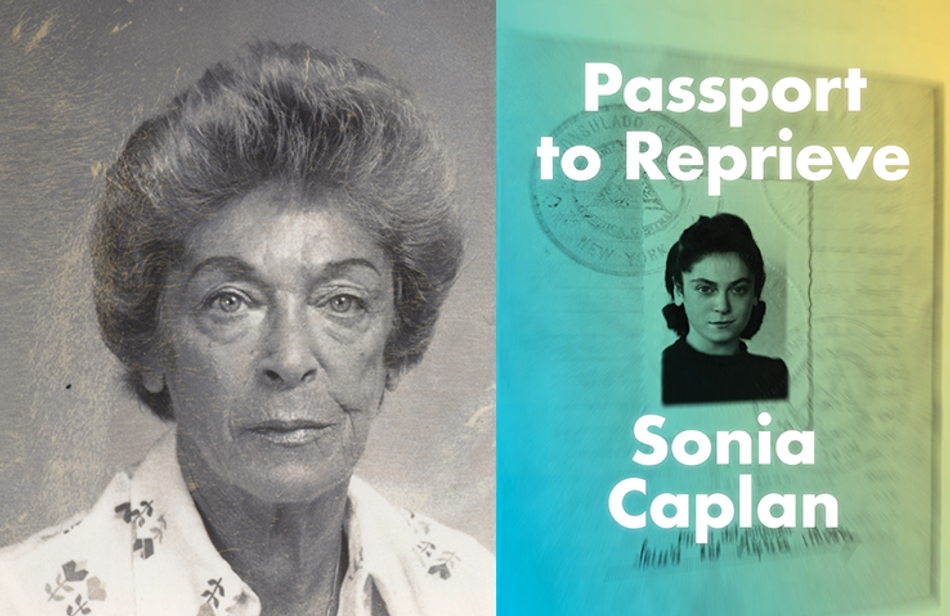

Remembering Sonia Caplan

Today, January 27th, is UN International Holocaust Remembrance Day – a day to honour survivors and victims of the Holocaust and share their stories, which we do today and every day. We give life to survivor stories by publishing and preserving survivor memoirs.

Sonia Caplan was a seventeen-year-old girl living in Poland when the war began. She used false identity documents to shield herself and her loved ones from deportations and survived a ghetto and internment camps. We had the privilege of recently publishing Passport to Reprieve, her beautifully written memoir. We hope you’ll take some time today to read survivor stories like Caplan’s, who was released from an internment camp just over 77 years today, and learn about the Holocaust.

Passport to Reprieve – The Passport

In late fall 1940, we received what was to become Father’s most significant and crucial letter during the entire period. In it, he told us that he had become a Nicaraguan citizen and that, according to the laws of Nicaragua, the same citizenship had been conferred on us, his family. “Be of good cheer,” he wrote, “for your new passports are on the way, and, as foreigners, you will be permitted to join me.”

Our first reaction was that of utter disbelief. In our boldest dreams of rescue, such an esoteric, unique possibility had never occurred to us. It bordered on magic and the supernatural. How did Father manage all those miracles? We marvelled at the constant, unrelieved thinking about our plight that he had been engaging in to come up with such mind-boggling ways to be useful to us. We could almost physically feel his presence, despite the distance separating us, for in his heart and mind he was not really away at all.

After our initial sense of wonder and exultation had subsided, I did some serious thinking and began to worry all over again. While it was true, I mused, that we might have a better chance of getting an exit visa as neutral aliens, how were we going to convince the Gestapo that the whole thing was genuine? After all, everybody knew that we had been living in Tarnów for many years, and that Father had gone to Canada, not to Nicaragua. I argued with myself that the Gestapo did not know it, and our friends were not about to enlighten them. Worn out from our endless talks all starting with, “Wonderful, but what if...?” the three of us finally decided to cross this newest of bridges when we came to it.

We came to it soon enough. Toward the end of 1940, the Polish postman brought us a thick manila envelope, covered with stamps and official-looking seals on both sides, on which the return address read: The Consulate General of the Republic of Nicaragua, New York, U.S.A. We were practically falling over one another to have a look when the contents began to emerge. Finally, while we held our breaths, Mother took out three light-blue folders. Even though Father had alerted us to their imminent arrival, it was still beyond belief to discover that they were actual passports, one for each of us, with recent photos of ourselves (which we had sent to Father earlier on his request) staring at us from the page, with unmistakably Spanish print listing the usual passport particulars, and with a highly conspicuous, large stamp of the Republic of Nicaragua across the printed information. We realized that the passports had been issued in New York and were definitely genuine; we had enough experience, by now, to spot forged documents.

I had practically given up all efforts to obtain the elusive exit visa, but I was now catapulted into action once again. First, I discussed the new situation with my trusted friends, Meyer, Jurek, Resia and Klara. They handled and studied my passport with reverence approaching awe. My father, whom they had all liked and respected, rose in their estimation to almost God-like proportions. He seemed to be able to accomplish what nobody else could or dared imagine — the impossible. Later, on sober reflection, they all counselled me that if I wanted to turn the extraordinary documents to our advantage, I had to register our new status with the puppet Polish authorities as well as with the Gestapo. At that point, I began to feel as though the exchanges between Father and us were like some carefully staged game of volleying a ball back and forth. The ball was now in our court. It was our turn to act.

My friends’ advice confirmed the

decision I had already made but on which, at least for the moment, I was too

frightened to act. All the “what ifs” haunted me, robbing me of my sleep, and

making me go robot-like about my daily chores. I thought of the murders,

tortures and hastily dug graves I had both seen and heard about, and feared

that we three would become added drops to the huge bloodbath as soon as we came

near anyone wearing a cap with a skull and crossbones on it. But I also knew

that I could not delay much longer what was obviously necessary to do. Besides,

if I did not take all possible steps, it would be tantamount to the betrayal of

Father, who, thousands of miles and a whole battered continent away, was

watching over us, never stopping his attempts to perform the miracle of our

reunion. As inaction was unthinkable, I plunged in.