Blog

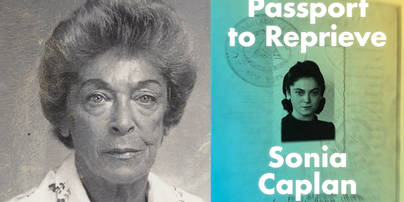

Remembering Sonia Caplan

Today, January 27th, is UN International Holocaust Remembrance Day – a day to honour survivors and victims of the Holocaust and share their stories, which we do today and every day. We hope you’ll take some time today to read survivor stories like Caplan’s, who was released from an internment camp just over 77 years today, and learn about the Holocaust.

Kol Nidre in Auschwitz

In her memoir, A Cry in Unison, Holocaust survivor, educator and human rights activist Judy Weissenberg Cohen tells the story of how she and her “camp sisters” in Auschwitz-Birkenau observed Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement.

Too Many Goodbyes: The Diaries Of Susan Garfield

Read an excerpt of Susan Garfield's memoir, “Too Many Goodbyes: The Diaries of Susan Garfield”

Confronting Devastation: Memoirs of Holocaust Survivors from Hungary

From idyllic pre-war life to forced labour battalions, ghettos and camps, and persecution and hiding in Budapest, the authors reflect on lives that were shattered, on the sorrows that came with liberation and, ultimately, on how they managed to persevere. Editor Ferenc Laczó frames excerpts from some twenty memoirs in their historical and political context, analyzing the events that led to the horrific “last chapter” of the Holocaust — the genocide of approximately 550,000 Jews in Hungary between 1944 and 1945. Forced exclusion and social integration, a worsening socioeconomic situation and the preservation of a few freedoms, mass violence and the seeming normality of everyday interactions: these were the polarities that defined Jewish experiences during the Hungarian years of persecution between 1938 and early 1944. Stories of the experiences of Hungary’s Jews in these years are remarkably diverse and even contradictory — which of the aforementioned experiences predominated in the life of individuals depended on their social status, age, gender and exact location, as well as sheer luck. These selected excerpts from memoirs of survivors offer precious insights into the contradictory experiences of everyday life, while also showing the worsening exclusion of those years.* Text adapted from Ferenc Laczó’s foreword to the Daily Life section of Confronting Devastation: Memoirs of Holocaust Survivors from Hungary.Read an excerpt:Shattered Dreams by Dolly Tiger-ChinitzMemory is like a stained-glass window. Every little piece fits together, but every little piece should be your own. As the window grows, your personality is formed. You will view the world through this window for the rest of your life. Everything that happens to you that you remember, and the way you place that memory into your window frame, will make you the person you are, different from everyone else in the world. Not only is what happened to you important, but also how you view what happened to you. And while I will try to give a more or less chronological account of what happened to me, where and how, I will sometimes digress and give you a little bit of that coloured stained glass that formed my window on the world. Life, at first, seemed idyllic: walks in the many beautiful parks of Budapest, or on Margaret Island where we plucked daisies and braided them into wreaths for our hair or picked horse-chestnuts to later fashion into doll-sized furniture; the Gellért Hill with the concrete slides in the summer and sledding in the winter; the beautiful chapel carved out from the rock, complete with a cave where a hermit dwelled. The Korzó on Sunday mornings, where we met other young girls being paraded by equally beautiful and fashionable mothers. But Mari and I were the only twins I can remember, which made us feel very special. Budapest was a dream city. Tourists crowded the outdoor cafés, the women were chic, the cafés noisy and the air heavy with perfume, excitement and joie de vivre. The Prince of Wales visited, and the city was abuzz with his antics, with the debauchery that was too much for even the fun-loving Hungarians. Spring was a time when on street corners young girls with round wicker baskets offered tiny bouquets of violets for sale, when the horse-chestnuts and the acacia trees were in bloom, when the amusement park opened its gates again and members of society went to the Gundel restaurant. Winter was the season when elegant people hurried to the cafés, the restaurants and the theatres, when the shore of the Danube River was transformed into a pine forest of Christmas trees for sale, and smells of incense wafted out of churches where the beautiful nativities were set up — our governess smuggled us in frequently. Christmas cards were displayed on the street by heavily clad women, and the smell of roasted chestnuts drifted in the bitingly cold air.Jews and other distrusted social groups were excluded from military service but were not relieved from having to serve the country and its army. Compulsory labour service (kötelező munkaszolgálat) was established by law in 1939 for individuals the regime deemed unreliable, targeting mostly Hungarian Jews. By 1940, there were approximately sixty units consisting entirely of Jewish labour servicemen. The enrolled individuals were not allowed to carry weapons and worked mostly on construction sites and in mines. Upon Hungary’s entry into the war in 1941, labour servicemen also often had to perform life-threatening tasks during combat, such as clearing minefields, and tens of thousands of servicemen perished during the war. The personal stories here offer intimate perspectives and numerous intriguing insights into this unusual and sinister institution.* Text adapted from Ferenc Laczó’s foreword to the Labour Battalions section of Confronting Devastation: Memoirs of Holocaust Survivors from Hungary. Read an excerpt:Like Slaves in Pharaoh’s Time by Itzik DavidovitsIn 1941 I arrived in Pétervására and was taken to an open field in an abandoned village. There were barns all around the fields. I couldn’t wear my own clothes. I was given a uniform and a hat, but no shoes, so had to use the shoes I was wearing. There were only Jews here, and we had Hungarian soldiers watching over us. I quickly started to realize that I was not in the army as a soldier, but instead was a prisoner of forced labour, like the Jews who were slaves in Pharaoh’s time. Sentenced to hard labour by the Hungarians, I was forced to build their roads and dig their trenches, with little food and shelter and under inhumane conditions. We were routinely beaten and tortured. The Hungarians told us that we had no privileges except to die. The Hungarians didn’t like it if we didn’t speak their language, but I couldn’t speak Hungarian; I spoke only Yiddish and Romanian. Every day I would write letters home to my mother and to my girlfriend, and every day I hoped and prayed that I would receive letters back, but I never did. Then one day the Hungarian soldiers showed us what they were doing to our mail. It was a letter from my girlfriend. They brought it to me and showed me that they had this letter from her and then they ripped it up in front of my eyes. They said that if our mail wasn’t written in Hungarian they would tear it to pieces. Up until July 1942 we still had army clothes, but that all changed when we reached Jolsva (now Jelšava, Slovakia), our last stop before the Soviet front. We were given orders to write home to our families to ask them to send us civilian clothing. We each had to have our own suitcases with our names on them and we had to get blankets from home. The only things they gave us were a cap and boots. When our suitcases arrived, I had to give in my uniform and change into the civilian clothes my mother sent me. One night after dinner, the head officer in charge of our division came out and lined us up. He was our new commander, and would prove to be more brutal than our last one. He proceeded to say that we had been selected to go to the front to dig trenches for the Hungarian and German soldiers. He said that it was our duty to obey orders, and that whoever did not follow orders would be punished or shot. He was speaking directly to us, the Jews. He turned to the Hungarian soldiers who were not Jewish and said, “Your duty as Hungarians is to make sure that the Jews get their work done and that they obey your orders. If they don’t obey, make sure they are punished or shot.” He also told his officers that the sooner they kill all the Jews, the sooner they will return home to their families in Hungary. The first day, we marched all night. By morning, ten of us had been beaten to death for no reason at all. Then we arrived at the front near the edge of the Don River. There were landmines everywhere, which we were ordered to clear for the Hungarians. We proceeded very carefully so as not to get blown up. We then started to build roads for the Germans and dig trenches with our shovels and picks. We dug trenches deep and wide enough to hide a tank. We had to work very hard as the ground was like concrete. We worked through the night so that we would not be seen, and during the day we marched about one and a half kilometres back to a village. We slept during the day in dilapidated, abandoned houses left behind by civilians.A snapshot of life before the warClockwise, from top: 1. Kati Horvath and her husband, Paul (Pali), on their wedding day. Budapest, Hungary, 1938. 2. Eva Kahan and her fiancé, Lajos, during their engagement. Óbuda, 1944. 3. László Láng with a friend from MIKÉFE (Hungarian Jewish Craft and Agricultural Association). Budapest, Hungary, 1942. 4. Susan Simon (front, left) on vacation with her family in Siófok, Hungary, early 1940s. 5. Itzik Davidovits’s family before the war. Back row, left to right: his sister Esther; his mother, Feige (Fanny); his brother Simcha; and his sister Ruchel. In front, left to right: his sisters Brauna (Betty), Henia and Frieda, and Itzik. Remete, Romania, circa 1932. March 19, 1944, marks the beginning of the Hungarian “year of extermination.” The memoir excerpts describe experiences within the short-lived ghettos in Hungary outside of Budapest, as well as the mass deportations that followed the creation of these ghettos between mid-May and early July 1944. The majority of Hungary’s sizable Jewish population, about 437,000 individuals, were deported, nearly all of them to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Most of those deported were murdered almost immediately upon their arrival there. Only a small fraction of Jews deported from Hungary in those months were sent to other camps.The approximately 100,000 Hungarian Jews who survived the initial selection round in Auschwitz-Birkenau — and all our memoirists recalling this most infamous camp complex by necessity belong to this minority — were used as forced labourers and were often transported to other camps. As many camps were evacuated amidst the final collapse of the Nazi regime to pre-empt their liberation by the fast-approaching Allies, their gravely weakened inmates were forced to march towards unknown destinations. The disturbing memories of these deadly marches often proved to be as traumatic as those of the camps.* Text adapted from Ferenc Laczó’s foreword to the Ghettos and Camps section of Confronting Devastation: Memoirs of Holocaust Survivors from Hungary. Read an excerpt:Amid the Burning Bushes by Helen Rodak-IzsoThe tragic day arrived when our street was to be emptied. We were being deported. We felt that we were looking around our home for the last time. We had to be ready to leave, since the Hungarian police were waiting for us, but we weren’t aware of what was happening around us. We were being forced to leave this place, where we had been together, where we had had our meals, talked, read books. Our life was being halted for some reason, but why? We had spent so many happy hours here, simply living the life of a family. We looked around to say goodbye to the familiar furniture, pictures, walls, and all of a sudden everything came alive and felt important. We discovered things that we hadn’t bothered to look at before. Oh, how it hurt to close the doors behind us! Once more we looked down at the garden, which was blooming in the usual spring colours. The sky was blue, but for us everything was grey. … The next tragic date was June 2, 1944, and it arrived just like the dreadful day of an execution: it was now the turn of our group, the fourth and last one in Kassa. We were forced to leave our hometown and enter occupied Polish territory. From the moment of our entry into Auschwitz-Birkenau, we were frightened all the time, wondering what more could come next. We kept on thinking all the time, yet we were trying to avoid the question we feared the most: what had happened to our dear parents upon our arrival? We were too afraid to believe what we had heard on the Appellplatz. The dreaded notion that we had been deceived slowly crept into our minds, and with closed eyes and trembling hearts we tried to hope against hope. We were not awake; we were in a daze, just moving about mechanically. We didn’t grasp yet what was going on, that we had lost our family, our home and everything. Even the little bag with our most cherished family pictures had been brutally and senselessly taken away from us. It dawned on us that we had no right to anything anymore. There was no way out, and it felt as if a dark curtain had descended in front of us, blocking the view to the outside world. The gnawing pain became unbearable, but this was not the place or time for emotion. We were deprived of everything that makes a human being into a person. Meanwhile the gas chambers were working full time.Budapest was home to the second-largest urban Jewish community in Europe prior to World War II, and the memoirs recount the unique horrors faced by these Jews during the Holocaust. After Regent Horthy was removed from power in mid-October, the ruling Arrow Cross forced the masses of Budapest Jews — who had already been segregated into individual buildings but not into separate areas of the city — into two separate ghettos. Whatever semblance of order still remained in the capital after mid-October now broke down as Arrow Cross thugs, who were often very young, started to terrorize the citizenry. They randomly murdered thousands of the surviving minority of Hungarian Jews, including by shooting them into the icy Danube River. Along with the threat of death from illness or starvation, the Allied air raids constituted another source of constant danger for the Jewish population still in Budapest — a danger shared with the other inhabitants of the city.* Text adapted from Ferenc Laczó’s foreword to the Budapest section of Confronting Devastation: Memoirs of Holocaust Survivors from Hungary.Read an excerpt:The Light in a Dark Cellar by Susan SimonWhen it all started, I was more afraid of the sirens than the bombs. The drawn-out, high-pitched blast seemed to land right inside my head, seeping down to invade my heart till it froze in terror. As the war progressed, sirens were followed by explosions, and I learned to reserve my fears for the latter. Eventually there were no sirens at all; life turned into a perpetual night in underground cellars, where the sound of bombs and buildings crumbling were all we could hear. In the early stages of the war, with sirens alerting the public, Rozi and I had to grab a bag filled with food, drink, a first-aid kit and toys and run as fast as we could. If I was in the washroom, Mother waited for me. When the sirens were not enough to penetrate my childish sleep at night, she woke me up and urged me to hurry. In the cellar we gave silent thanks for arriving in one piece. Windows were covered with black paper, and cracks were filled with caulk to shroud our house in darkness at night. Rumours circulated about cellars collapsing, as well as the buildings above them, but Mother didn’t pass on such gossip to us so the threats would not ruin our hopes. We had to wear a yellow star above our hearts to identify us as Jews, and we were allowed to leave our homes for an hour or two at certain times to buy food. Scared to walk with our stars, our heads buzzing with horror stories about how Jews were killed on the streets, we rarely stepped outside. It didn’t help that Nazi propaganda was spread on huge posters, glaring from rooftops. One of them showed a little girl covered with vivid splashes of blood, holding a toy that had exploded in her hands. This shocking scene blamed the Allied forces for throwing down explosives in the shape of toys from their airplanes. In truth, only the Nazi imagination could invent such crimes. Confused, Rozi and I thought of this disturbing picture before we fell asleep, particularly because the little girl on the poster had a sweet baby face with big blue eyes, just like Rozi. This likeness terrified her. The Arrow Cross, the Hungarian party closely allied with the Nazis, took over the government on October 15, 1944. Shortly after this event, they passed a law ordering the Jews in the capital to move into a ghetto. My family had already escaped a ghetto in the small town of Gyöngyös; Mother didn’t want to enter another one. She decided that we should hide.The stories of liberation highlight both the hopes and new sorrows brought by the end of the Nazi genocide. The authors recall the often downright brutal treatment they received from members of the Red Army, their nominal liberators, including acts of gendered violence (another taboo topic in post-war Hungary) and the often insensitive or even malevolent approach to their recent past by other members of Hungarian society and the emerging communist establishment. The memoir excerpts paint a complex and nuanced picture of liberation.* Text adapted from Ferenc Laczó’s foreword of the Liberation section to Confronting Devastation: Memoirs of Holocaust Survivors from Hungary.Read an excerpt:To Start off as a Christian but to Arrive as a Jew by Eva KahanOne morning we finally saw the first Soviet soldiers. We were relieved and happy to reach the day we had been waiting for so long. Unfortunately, these soldiers turned out to be a great disappointment. They were wild, unreliable and cruel. I was just as afraid of them as I had been of the Germans. Of course, we understood that they were fighting for their survival and hated all Hungarians (Jewish or not). After being on the front lines for years, they suffered and saw so much that they forgot how to be human. Stealing, raping, killing meant nothing to them. The war was still far from over. We lived in the northern part of Pest, and the Germans were still holding on downtown, where the ghetto was located. … Soon, after we heard that the Soviets had liberated the ghetto, we went to see my grandfather. He was okay because he was with his sons and their families all along. I heard from him that my father was in the ghetto in the house of the Jewish Council. We were surprised. Why would he be in the ghetto when he had false documents? Well, we immediately went there and found him sick, lying on a wooden bench. We wanted to take him with us but he was too weak to walk. We promised to be back for him. The next day we borrowed a sled and took a bagful of food with us and went back to the ghetto. I will never forget the children on the street begging for food; as we gave some to one or two of them, a whole bunch kept on following us. Also engraved in my memory of the ghetto is the heap of corpses in a yard, bodies of mostly old people and children in their underwear, on top of each other.ABOUT THE EDITOR Ferenc Laczó is assistant professor in history at Maastricht University. He is the author of Hungarian Jews in the Age of Genocide: An Intellectual History, 1929–1948 (2016) and co-editor (with Joachim von Puttkamer) of Catastrophe and Utopia: Jewish Intellectuals in Central and Eastern Europe in the 1930s and 1940s (2017). BUY THE BOOK ARE YOU AN EDUCATOR? Place your order here.

The High Holidays Engraved in Memory

Holidays for Love and Family: For Elsa Thon, the High Holidays remind her of the first time her parents met in 1913. In her memoir, If Only It Were Fiction, she shares this story: their love at first sight at the synagogue in Kharkov, then ruled by Russia, on the evening of Rosh Hashanah. She reveals, at the same time, how the values inspired by this feast united them through the turmoil of World War I and the Russian Revolution, until her birth.“The Russian military allowed the young Jewish soldiers to pray during the High Holidays, Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, in a synagogue in Kharkov, close to where they were stationed at the time. It was there that my parents met for the first time. Both remembered their encounter and, separately, related exactly the same story — it was love at first sight. They prayed for the coming year to bring health and happiness, as was the custom. History followed its course, and their story unfolded…When she met my father at the synagogue, my mother’s life changed once again. They fell in love, knowing that my father could be sent to the front line at any time. In 1913, when his departure was imminent, I presume that our parents swore faithfulness, hoping that some day he would return from the war and they would marry. They allowed themselves to dream in spite of the dangers of war. When he was called to the front line, they relied only on their youth, hope and the strong love that brought them together.Although all this happened before I was born, the story was told and repeated so many times that it became engraved in my memory.” Elsa Thon, 1945Betty Rich has very different childhood memories of the High Holidays. In her memoir, Little Girl Lost, she expresses her love for the festive family traditions of Rosh Hashanah, but displays dismay at the Orthodox religious rituals practised by her mother on Yom Kippur. “During certain Jewish holidays, such as Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year) and Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement), adults had to be in the synagogue from morning until sundown. Their children came to visit them sometime during the day. My parents, being Orthodox, were separated — women were upstairs in the balcony of the synagogue and men were on the main floor. I remember visiting my mother on those very holy days. The air was heavy and sticky and my mother, like all the women on Yom Kippur, was praying and crying very loudly. This was the day that they ask God’s forgiveness for sins committed during the whole year. I was both appalled and scared by it. I couldn’t understand why my mother would ask forgiveness for sins that, as far as I knew, she had never committed. I also couldn’t fathom the whole idea of praying, addressing God and constantly praising him, using such powerful adjectives. Why? What for? I didn’t dare to ask, so I would just fulfill my obligation to my mother, feeling sorry for her. Seeing her crying and humbling herself so much deeply touched me, but angered me at the same time. For the most part, though, the Jewish holidays were a happy time in our family, a time of tradition and reunion that, to me, had nothing to do with religion. I used to love those holidays (except Yom Kippur, as I just mentioned). The transformation from an atmosphere of tension and worries over our constant financial problems was so great that it’s no wonder that when I was happy I used to say, ‘I feel like it’s a Jewish holiday today’.” Betty Rich, then Basia Kohn, with her father, mother and younger brother before World War II. Left to right: Betty’s father, Chaim Moshe; Betty at age twelve; her younger brother, Rafael; and her mother, Cyrla. Zduńska Wola, 1935.Like Elsa Thon, many survivors share holiday memories that include people and places that did not survive the war. Fred Mann shows us the traditions and dress habits of men on Yom Kippur in his hometown of Leipzig, Germany, before the war. His memoir, A Drastic Turn of Destiny, depicts the special importance for him of the prayer service at his synagogue, which was the last service Fred spent with his family before his synagogue was destroyed by arson during Kristallnacht, in November 1938. “Our last visits to the synagogue took place on September 25–27, 1938, for the High Holidays of Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, and October 4–5 for Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. In prior years we attended every High Holiday as well as the more joyous occasions such as Simchat Torah, when lots of sweets were handed out to the children. We went to at least one Shabbat service a month, and this was always followed by a visit to the Rosenthal Park where we met with our school friends. Unlike all the previous years, in 1938 not a single man appeared in the customary morning coat or top hat...The longest day of the High Holidays was Yom Kippur, when my parents remained in synagogue for almost the whole day. The services lasted until late afternoon and my brother and I were sent off to a restaurant for lunch only to return after eating to slip in and out of the ongoing religious services. In previous years the men’s attire was probably as unusual as one would see anywhere. Many men wore top hats, morning coats and striped pants, and on the lapel of their morning coats they proudly displayed their German World War I medals. This, they thought, marked them as good Germans. They looked as if they were presenting their credentials to God and requesting another year of accreditation. The synagogue had an excellent choir and a very harmonious organ that played during the service. The reverberations and echo were so well tuned that the synagogue was sometimes used for choral performances. The cantor had a most resonant voice and could easily have qualified as an opera singer.” Fred Mann, Leipzig (Germany) 1939.Rosh Hashanah under Nazi SurveillanceDuring the Holocaust, the Nazis sometimes chose the High Holidays as a time to humiliate and inflict more suffering on the Jewish community. This was the case for the Jews in Dukla, Poland, who soon after the German occupation of their country in September 1939, celebrated Rosh Hashanah under Nazi surveillance. In his memoir, The Vale of Tears, Rabbi Pinchas Hirschprung describes the ceremony and his community’s commitment to maintain its faith and culture despite persecutions.“On the eve of Rosh Hashanah, with prayer books in their hands, fear in their hearts and reverence for God on their faces, men, women and children poured into the synagogue.Never before in Dukla had it felt so much like the Days of Awe* were upon us as it did that evening. The holiness of the Day of Judgment* had placed its seal on the town. Heads lowered, with measured steps, the Jews quietly and calmly shuffled by while Nazi soldiers with cameras photographed “the Jewish procession.”...Unofficial rumours were circulating that Warsaw had already fallen. Of course this piece of news heightened the significance of the Day of Judgment. Our fear kept growing and growing and growing.In the morning, the synagogue was again full of people with ‘instill Your awe’ clearly visible in everyone’s face. We had completed the morning service and had begun preparing for the blowing of the shofar. First, we sent out a ‘reconnaissance party’ whose task it was to ascertain whether the ‘voice of the shofar’ could reach the ears of the enemy. After that we sealed the synagogue gates and then we sounded all one hundred blasts at the same time, furtively and hurriedly, ‘in a single breath.’ Although the sounds were quiet, they nevertheless produced a strange apprehension, and the stillness in the synagogue resembled that of a cemetery.Having carried out our covert operation, we threw open the gates before beginning the additional prayer service. The cantor recited the Shemoneh Esrei* with passionate fervour and profound sensitivity. The words of the prayer that the cantor sang so sweetly gave such pleasure to those praying that everyone felt refreshed and renewed. Feelings of degradation and dejection dissipated, and the congregation was infused with feelings of exaltation and spiritual elevation.These feelings, however, did not last long. Nazi soldiers arrived to destroy the fragile calm and delicate tranquility that had so tenderly soothed us.The cantor, transported into the ‘higher realms’ of prayer, had not a clue as to what was happening behind his back. He continued praying with the same passion, but the congregation had become distraught and alarmed. Our first thought was that this visit from the Nazi ‘guests’ was due to the blowing of the shofar. But this suspicion vanished after the Nazi visitors ordered us to carry on quietly with our ‘ceremony.’ They were evidently curious to observe the service. For a few minutes they remained seated in the seats that some members of the congregation had offered them. Then a few of the Nazis got up from their places, set up their photographic equipment and photographed the congregation. When they were finished photographing those praying, they photographed the cantor, who was completely indifferent and carried on with his prayers as though the whole matter had nothing to do with him.Afterward they went over to the Holy Ark and gave one member of the congregation the ‘honour’ of opening the Ark so that they could photograph the Torah scrolls housed inside. Having completed their work, they left and everyone took a deep breath.”*Days of Awe Also known as Ten Days of Repentance, this is another term for the first ten days of the Jewish year, beginning with Rosh Hashanah and ending with Yom Kippur — a time of reflection, repentance, prayer and forgiveness.*Shemoneh Esrei The Jewish prayer that is recited three times daily while standing and facing Jerusalem.*Day of Judgment Another name for Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, referring to it as the time when humankind undergoes Divine judgement.Rabbi Hirschprung (centre) with Rabbi Menachem Mendel Eiger (left) and Rabbi Yechiel Menachem Singer (right). Poland, 1930s.First Rosh Hashanah in Canada The eldest of seven children, Willie Sterner was the only one of his siblings to survive the Holocaust. After the war, he lived in displaced persons camps in Austria, and in 1948, he and his wife, Eva, immigrated to Canada. In his memoir, The Shadows Behind Me, he describes his first celebration of Rosh Hashanah in Halifax, the day after his arrival in his new country. Greeted by people from the local Jewish community, Willie reconnects with the family spirit of this holiday and finds joy in discovering the cultural differences of the traditions at the synagogue in Canada. The holiday becomes a way for Willie to learn about his new home.“When our ship docked in Halifax, it was the eve of the Jewish New Year — Rosh Hashanah — and some people from the local Jewish community came aboard to ask if we would like to stay in the city over the High Holidays so we wouldn’t have to travel by train to Montreal during the holiday. Some of our people, including my wife and I, decided to accept that generous invitation. The Jewish people in Halifax were very friendly and spoke to us in Yiddish, so we felt at home. They took all of us from the port to a nice hotel. The next day was Rosh Hashanah. In the morning, a Jewish man from the Halifax community came to our hotel to tell us that he would take us to a synagogue for the holiday services. We got into cars that were waiting outside the hotel and drove to a modern synagogue. The service was a little different from the services in our former country, but it was nice and the cantor was very good. Rosh Hashanah in Halifax was the first real holiday we’d had since we had been separated from our loved ones in 1942. The holiday was also special because it was our first Rosh Hashanah in Canada.After the service, we were taken to visit Jewish families in Halifax. Our group — the Shnitzer family and my wife and I — visited the home of the Zemel family. The Zemels gave us a warm welcome and we felt at home with them. They were very friendly. Because Eva and I hadn’t been to a Jewish family holiday for so many years, we felt that we were members of their family. Mrs. Zemel placed all of us at a large table in the dining room. Eva stood up at her place and asked Mrs. Zemel if she could be of any help. Mrs. Zemel and all her guests were pleasantly surprised. Mrs. Zemel took Eva into the kitchen and they came out with delicious, traditional food prepared especially for Rosh Hashanah. I was so very proud of Eva — she was a great help to Mrs. Zemel and was appreciated by our hosts and their guests.Eva and I were glad that we had stayed with such warm people in Halifax, but after the lovely holiday it was time to continue on to Montreal. It was hard saying goodbye to the Zemels because we already felt so close to them. They asked us to stay in Halifax — they said that they had a small Jewish community and that we would be happy there. But our destination was a transit camp in Montreal and then Toronto, where we had been assigned to go. Eva and I will always gratefully remember the warm welcome we got from the Zemel family and the whole Jewish community in Halifax.”Willie landing in Halifax on the eve of Rosh Hashanah 1948.

Always Remember Who You Are

Anita with her parents, Edzia and Fisko. Synowódzko Wyżne, Poland, 1937. Miraculous EscapeWe didn’t know where my mother had been taken. Nobody knew anything in our part of Poland. We had heard rumours of murder by gas. But who could believe this? The Nazis deliberately withheld information from their victims for fear of resistance or reprisal. They were the kings of deception. After this incident, my father seemed to have lost his will to live but became desperate to protect me, his only child. He knew that if I remained in the ghetto, I would be caught in the next Aktion. He did not know exactly what had happened to those who were taken, but he understood that they were not coming back. We heard that the transports from our region were taken to a camp in the small town of Bełżec.The rumours that circulated about the mass murders underway there were terrifying. My father no longer kept any secrets from me. Since he was desperately trying to save me, he told me exactly what was going on. I trusted my father and knew that he would do everything in his power to keep me safe.Once the Germans realized how valuable my father’s accounting skills were, they moved him into the office hut in our hometown permanently. There he came into contact with non-Jews, who were permitted to live outside the ghetto walls. My father quickly befriended a Polish Catholic man, Josef Matusiewicz, who had been brought from his town to serve as the stock-keeper.[…]My father did not know where to turn or what to do after the loss of my mother. He was scared of the day when he would come home from work to find that I, too, had disappeared. But asking Josef to help me was a dangerous proposal. In German-occupied Poland, strict laws prohibited people from helping Jews in any way, including providing food rations or hiding Jews in their home. Any person caught or even accused of helping a Jew risked their own life, as well as the lives of their family and, sometimes, communities.[…]When he agreed to take me, Josef knew he was violating Nazi law. Josef had not been a family friend, and I did not know him. Many years later, I learned about the night Josef told his wife that he wanted to bring a little Jewish girl into their home. He explained the situation and what he had been asked to do. Josef’s adopted daughter Lusia told me that her mother, Paulina, was dismayed by the request: “Are you crazy? You’re going to bring a little Jewish girl into our house? You’re going to endanger our lives, you cannot do that!” I believe that Josef was an extremely courageous man and responded that God would help. They were a very religious family and fervently believed that God would help them protect me. Josef saw my father’s desperation and could not look away. At tremendous personal risk, the decision was made to take me in. My father tried to prepare me for another major change. He explained that it was very important that I understood that he could not keep me safe. Every day in the ghetto was dangerous for me. I knew that being Jewish was dangerous. My mother was already gone. I did not want to lose him, too. My father reassured me that I would live with people who would be good to me and care about me. Life would be much better for me there than it was in the ghetto. Before we had come to the ghetto, I was terribly spoiled, an only child. Needless to say, after a year in the ghetto, I was not spoiled any longer. I did not want to go. But my father made it absolutely clear that I had no choice in the matter. I had to go. Otherwise, he told me, I might die. And I had seen death in the ghetto. I am not sure if I understood at the age of eight what it meant to die, but I knew that it was final.My father assured me that he would be fine, and that we would be together shortly. “It won’t take long. Everything will be fine. I’ll come and see you and I’ll take you home.…” He promised me everything a parent would promise an eight-year-old child. And so, when Josef Matusiewicz came to get me, I went along with him. I was petrified because I didn’t really know this man, whom I had met only a handful of times. I didn’t want to leave my father.Josef Matusiewicz’s position granted him special access to the otherwise restricted ghetto, and one night he was able to get into the ghetto to collect me. I had to say goodbye to my father. I clung to him and did not want to let go. When we could no longer delay the inevitable, Josef put me in a large bag and carried me out of the ghetto like I was a sack of potatoes. I was cautioned not to make any noise, not to move, not to draw any attention to myself. Years later I learned that there was a police station located right next to where we left the ghetto. I don’t know how Josef managed to take me out. It really was a miracle that we were not caught.About the AuthorAnita Helfgott Ekstein was born on July 18, 1934, in Lwów, Poland (now Ukraine). After the war, Anita and her aunt immigrated to Paris, arriving in Toronto in 1948. A dedicated Holocaust educator, Anita founded a group for child survivors and hidden children in Toronto, participated in the March of the Living eighteen times and has spoken to thousands of students. Anita lives in Toronto.Anita’s memoir is available for purchase here.

- 1

- 2