Adapting Education

Over the past decade, I have had the honour and privilege of travelling across Canada with many of the survivor authors who have published their memoirs with the Azrieli Foundation’s Holocaust Survivor Memoirs Program. During my travels, I often heard the survivors speak to different audiences, yet each time I listened to them, I was intrigued and fascinated. I’ve heard students say that hearing a survivor’s testimony affected them more deeply than any lecture, book or film relating to the Holocaust. And I agree — these are unforgettable and authentic moments that I have been fortunate to experience first-hand.

During the pandemic, Holocaust survivors who were willing to keep sharing their stories with students had to “pivot,” like most of us did, to using technology to connect with people. Although some Holocaust survivors are optimistic that they will return to speaking to live audiences when the pandemic is under control, they also recognize that new technologies have made speaking and engaging with students less strenuous and more accessible for them. They can reach larger audiences now, no matter where they are in the world, from the comfort of their homes. However, the survivors who do not have technological skills or access struggle to stay connected.

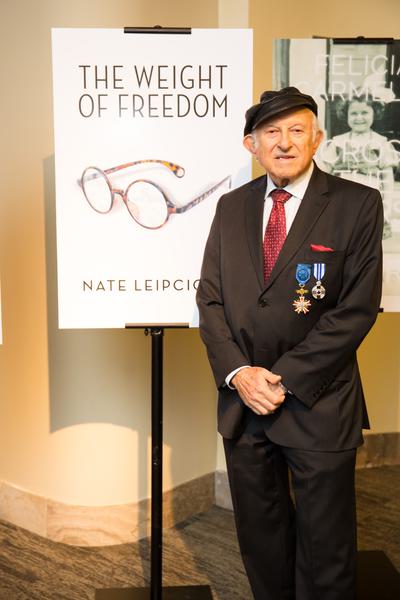

Nate Leipciger at the ten-year anniversary of the Azrieli Foundation's Holocaust Survivor Memoirs Program in 2015, which also celebrated the launch of his memoir.

Nate Leipciger, author of The Weight of Freedom, is one survivor who has embraced this new way of teaching and recognizes that while virtual interaction is different than in-person, it has its advantages. “We have to accept what is missing and do the best we can do with what we have,” he said, when I spoke to him recently. “During normal times, we didn’t think about it, but now it’s an exciting time to develop new opportunities to communicate far and wide. But it can never replace the feeling of a live, in-person presentation.”

Nate has been a Holocaust educator for over thirty years. He is well practised in adapting his talks to the comprehension levels of his diverse audiences and is able to forge a strong connection with people, no matter the platform on which he speaks. But when I witness Nate speaking in person to students, I am constantly awed by how he interacts with them, capturing their attention with his passion and genuineness. After a talk, students line up to shake his hand or even offer an embrace. This human connection creates a critical bridge between history and empathy.

But we are at a turning point in Holocaust education, and not only because many survivors are no longer doing in-person events. What will it be like when there are no longer any Holocaust survivors left to share their stories in real time? This is a question I am frequently asked at events.

As survivors advance into their late eighties and nineties, we face the reality that the window of opportunity to be able to hear a survivor speak in the present moment is quickly closing, leaving behind many unspoken stories. Sadly, this present generation of young people will be the last to hear a living voice say, “I was there.”

For me, Holocaust education will never be the same without the survivors, and I think that others who have heard survivors speak and seen the power of the connections they make will recognize this loss. Fortunately, we have the words that survivors wrote, the memories they chose to share in the memoirs that we publish. We also have interviews and films of our survivors, which will allow future generations to “meet” a survivor virtually, providing them with the opportunity to learn from the survivors long after they are gone.

I asked three Holocaust survivors who have published their memoirs and who have been speaking publicly for decades for their thoughts on the future of Holocaust education.

In years to come, when there are no survivors left to speak to students, how would you like to see Holocaust education taught? Can we still have a strong enough impact on audiences without the presence of survivors?

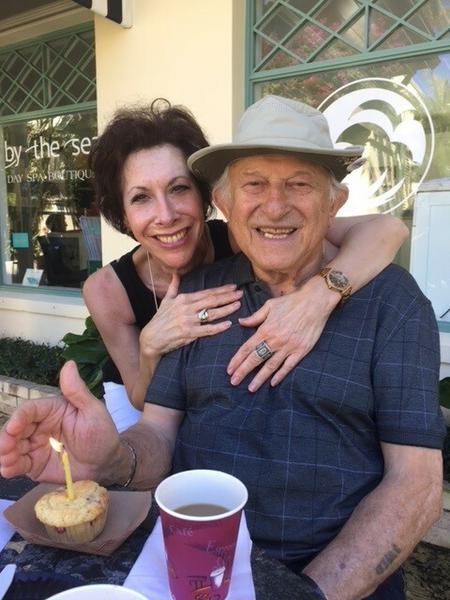

Elin Beaumont with Nate Leipciger in February 2018.

As a survivor, I believe I have an obligation to the previous generations to teach the next generations what happened, who the victims were and what life they had, and what the world has lost with their demise.

I think Holocaust education is now so well developed that our occasional presence, although missed in some instances, will not be that detrimental. Most educational facilities, universities and organizations do not depend on survivors’ presence. The next generations are well positioned to bring into the educational sphere new methods of transmitting our stories, and the effect our stories had on them. - Nate Leipciger

Nate Leipciger, author of The Weight of Freedom (2015), began speaking to students in Canada and internationally shortly after his father’s death in 1972. Nate knew that his father had been a wonderful storyteller, but now telling their history had become his responsibility. Nate became a long-time member of the International Council of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum and an educator on the March of the Living. In 2016, a year after his memoir was published, Nate travelled with Prime Minister Trudeau to Auschwitz-Birkenau, the concentration and death camp where Nate and his father were first incarcerated and where his sister and mother had been murdered.

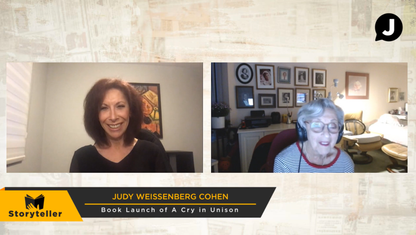

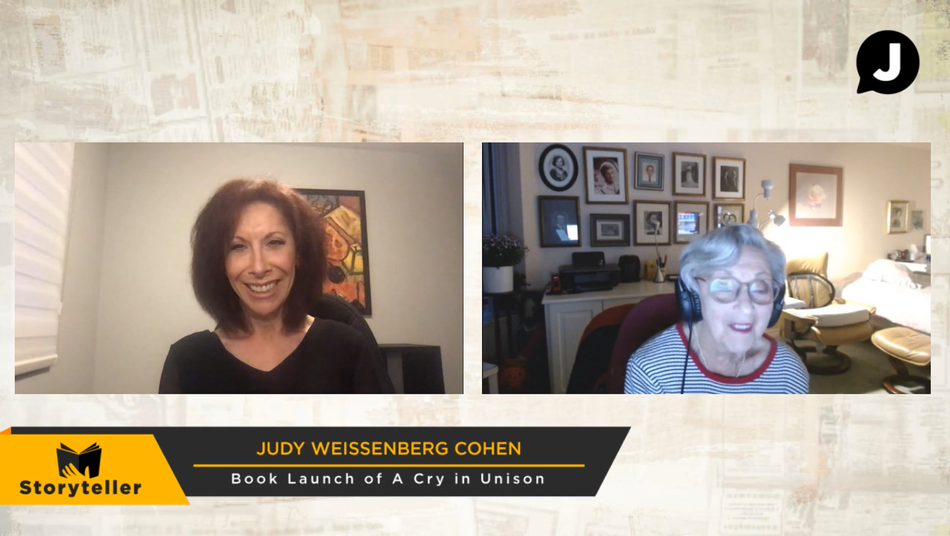

Elin Beaumont (left) speaking with Judy Cohen (right) at the virtual launch of her memoir, A Cry in Unison, in 2020.

There was this naive wish and hope, and maybe even belief, that what we are doing by our witnessing is going to create knowledgeable young people who, by learning from our stories, will understand that friendly behaviour to their classmates is the best way to get along, regardless of differences; and hatred hurts and causes unnecessary animosity. In other words, that knowing about the Holocaust would create better human beings. Yes, Holocaust education will continue without us, provided the generation at hand and subsequent ones will be properly educated on this complicated epoch and will be able to successfully combine knowledge of the all-important political, historical and social processes with their devastating effects on Jews, Roma and all other innocent victims. And it will be enhanced by written stories of families.

- Judy Weissenberg Cohen

Judy Weissenberg Cohen, author of A Cry in Unison (2020), has been a Holocaust and human rights educator and activist since the 1990s. After an encounter with neo-Nazis in the streets of downtown Toronto, Judy was faced with the reality that bigotry and antisemitism had not died with Hitler, and she was determined to do something about it. Judy began speaking about the Holocaust, and in 2001 she founded the pioneering website Women and the Holocaust — a Cyberspace of Their Own, which collects testimony, literature and scholarly material exploring the gender-based experiences of women in the Holocaust.

Elin Beaumont with Pinchas Gutter at his memoir launch in 2018.

I am a great believer in education. Education of the young about what happened, what shouldn’t happen and what is happening now. And I try to make them understand that it is up to them to try and change things for the better. I believe that change is possible but only if we all make an enormous effort to bring about a change in the political atmosphere where the truth has been completely forgotten and lies rule the world — like Holocaust denial and general denial of all the horrific things that are going on in the world at the moment. I hope that the little bit that I do has made some contribution to that end.

Holocaust education will continue when we are gone, but the quality of the education will depend on who is going to do the teaching. As far as the impact of the presence of survivors is concerned, this is precisely where Dimensions in Testimony can compensate for their absence, because the interaction between the student and the image is very vivid. I think this is the future of education. - Pinchas Gutter

Pinchas Gutter, author of Memories in Focus (2018), began speaking publicly in 2005 on a trip to Poland with a group of Catholic educators who were participating in the March of Remembrance and Hope. Pinchas was moved by their expressions of empathy and compassion throughout the trip, which then marked the beginning of his commitment to being a Holocaust educator. Pinchas was the first participant in the USC Shoah Foundation’s Dimensions in Testimony, a project that translates survivor testimonies into a 3D interactive digital interface that provides real-time responses to viewer questions.

These profound comments from Holocaust survivors illustrate what we will be missing when they are gone but can also act as guideposts as we move forward. My own experiences with Holocaust education make it clear how far we have come. When I was in public school in the 1960s, the Holocaust was not addressed in the educational system. But we have since seen an exponential increase in Holocaust education. The abundance of educational resources — memoirs, scholarly books, audio-visual testimonies, searchable encyclopedias and even interactive holograms — have provided teachers with ample material to help them teach the complexities of this subject matter. Modern technology has immortalized survivors’ memories, and we have made significant strides in Holocaust education. As the world changes, we at the Azrieli Foundation continue to develop innovative tools and resources that will help students have a deeper understanding of the Holocaust and survivors’ life experiences.

Elin Beaumont has planned and organized community and educational events and programs for the Holocaust Survivor Memoirs Program over the past thirteen years. She created the Toronto-based Sustaining Memories Program in 2011, which partnered volunteers with Holocaust survivors to assist them in writing their memoirs. This initiative produced ninety manuscripts, most of which are now featured on our website exhibits page. During the pandemic, Elin has organized and facilitated a number of virtual programs and interviews with survivor authors published through the memoirs program.