A Woman's Shoes

In my work as an editor of Holocaust survivor memoirs, there is a dynamic line of communication between past and present, between memories of what has been and the realities of now, between the page and me. It is the line that connects the storyteller and the listener, the person who experienced history and its traumas and the witness to those experiences. I see my responsibility to the narrator and to history as an active one: I am a memory keeper for the survivor, as well as for the people and communities that did not survive. And I am also an advocate for the reader.

These roles often seem contradictory. If I preserve the original language and syntax of a text, which is sometimes a translation or is written in the writer’s second language, a reader might get mired in trying to decode what is being said, and the story will become stilted and distant — like viewing a painting through a phone screen rather than in person, where it can wash over you, rattle you to the bone, upend the way you see. But if I change the language even a little, turn slightly in one direction or another, I risk trampling on the writer’s voice and memories with my own voice and the shape of my own experience. I am conscious as I write these words how intrusive and clumsy, how embarrassing, the process can feel, like realizing that I’ve left muddy footprints all over someone else’s living room floor.

Sometimes I think that working with narratives, and especially narratives of trauma, requires the precision of surgery. A few misplaced incisions and stitches and I will lose the life-blood of the story — and a sense of the person telling it. At times I become paralyzed by the extent of this power I have. What if that slight trimming of the text over here — never mind the seismic paragraph shifting and outright slashing over there — which I think clarifies a memory, actually changes its meaning or distorts it?

I have spent many long minutes staring at my screen, doubting my decisions — deleting, rewriting, deleting.

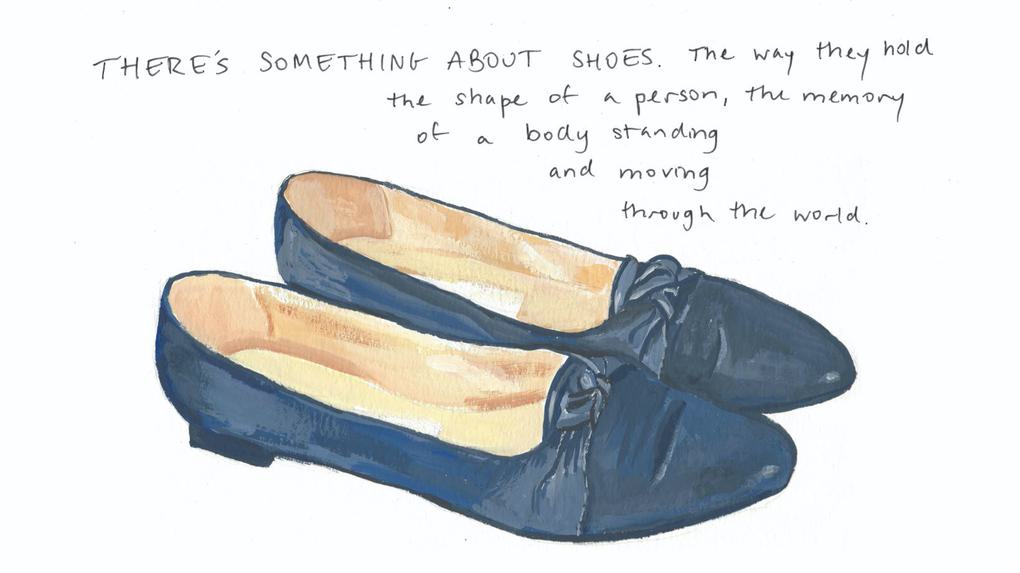

In response to this paralysis, I find myself wanting to bridge the gap between myself and the author — to create a psychic link to the inner life of the survivor — in order to become a person who has a right to mess about inside the language and the story in the way I do, in order to really understand what the author is communicating and help her do it well. I am trying to, not walk a mile, but just stand, in the survivor’s shoes, to imaginatively and empathically place myself in her experience. But this too has its risks.

When it comes to bearing witness to the experiences of survivors of trauma, scholars tangle over words like "empathy," "identification," "sympathy," and how they contribute to the ways we connect to testimonies of trauma. How much can we, or should we, try to find ourselves in others’ stories? What are the ethical implications of empathy — of objectivity? The historian Dominic LaCapra advocates for what he calls "empathic unsettlement," which requires finding that liminal position between closeness and distance, allowing ourselves to feel the pain that another person has experienced, but acknowledging that it is not our pain. This is an approach that makes space for an open-ended relationship with testimony, and an understanding that any narrative that imposes a neatness or redemptive reading on the testimony will be our own, that the experience of the survivor will always be more complex and unknowable than we can identify with or understand. Or as contemporary theories of history education would say, any understanding of the past has to include a conception of our own limitations of understanding (see, for example, the Historical Perspective concept in The Big Six: Historical Thinking Concepts, by Peter Seixas and Tom Morton).

My desire to find myself in the survivor’s story is not only emotionally taxing, it is also misplaced. I am not her. I have not lived in her time or had her experiences. And I will never truly understand what she went through. I will never stand in the survivor's shoes.

A story about shoes: It was Holocaust Education Week, 2019, and I accompanied Judy Cohen, the 91-year-old survivor whose memoir I was then immersed in — shifting passages, recasting sentences, checking dates and historical data — to a talk she was giving at York University. To my amusement, we both showed up in almost exactly the same retro wingtip brogues. I had inherited mine from a clothing swap several years previously and had worn them only twice since. I remarked on our matching footwear immediately, and several people at the event did as well.

As the morning progressed, Judy spoke as she always does — articulately, knowledgeably, and with the special kind of generosity that is the talent and the burden of those who have suffered profoundly and who are willing to delve into that suffering in order to educate and build awareness, to shed even a little bit of light. Judy expresses this hope for her story in the last lines of her memoir. Now is the time, she writes, when “future generations will search for and find the way to end this senseless hate and find common ground for the good of all humanity.”

Judy stood there giving her presentation for over two hours, and I couldn’t help but think about where else those now beautifully shod feet had been, where the events of Judy’s life had taken her and how she had responded, where she had been forced to go and the paths she had actively chosen to tread. In her memoir there is the description of her bleeding feet that were encased in a wire-and-wood contraption as she walked “a never-ending road, paved with utter, unadulterated misery” — a death march. There is the walk back to her home in Debrecen, Hungary, after she was liberated, her heart heavy with hope and fear at what awaited her, or didn’t. And then, years later, she stepped forward into a group of neo-Nazis who were chanting “White Power! White Power!” on a street corner in Toronto — her opening gambit in a decades-long career of activism and educating to combat Holocaust denial. Much later, there was a bold stride into the digital sphere when Judy realized that women’s voices from the Holocaust were still largely unheard. That was when she launched her website, Women and the Holocaust — a Cyberspace of Their Own, and began her pioneering work in the field.

The talk came to an end, and students began to filter out and drift toward the other room and the tables of free pizza. Some of them remained behind or returned with pizza in hand to engage Judy in conversation. And I began to fixate on the strange coincidence of our matching footwear, and to believe that it held a kind of gift for me. Maybe, I thought, I can't stand in this survivor’s shoes. I need to acknowledge that there will always be an unbridgeable gap between us and that I will never fully identify with her experiences. All I can do is make a commitment to show up, to remain empathically connected to her and to the richness of her life, to the love and the loss she has experienced, trying to understand while realizing that I will necessarily fail, trying to identify with her story and her life — but from a distance, firmly inhabiting my own, very distinct, pair of shoes.

Art by Devora Levin

Devora Levin is an editor, writer and artist in Toronto and is currently an editor and special projects coordinator with the Azrieli Foundation’s Holocaust Survivor Memoirs Program.