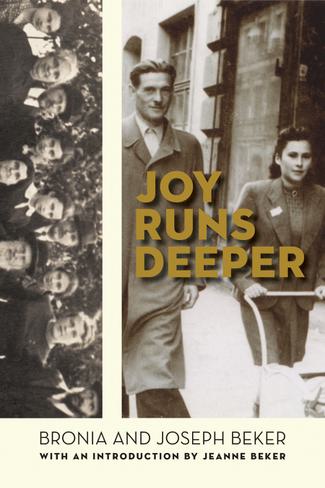

Joy Runs Deeper

Bronia Beker , Joseph Beker

Bronia Rohatiner and Josio (Joseph) Beker grow up in the shtetl of Kozowa, Poland, a small town filled with lively culture, eccentric characters and extended family. When nineteen-year-old Bronia meets the older, handsome Josio, she is charmed by his confidence and fearlessness. Separated when Josio is drafted into the army, reunited amid the chaos of the war, their connection endures as their persecution intensifies. After tragedy strikes Bronia’s family, Josio strengthens her will to live. When everything they hold dear is lost, together they build a new future.

Introduction by Jeanne Beker

Joy Runs Deeper

The Home that Was Lost

On July 21, a beautiful sunny day in 1944, I found myself sitting in the ruins of our house, crying bitterly. The little town of Kozowa, where I was born on December 9, 1920, had been destroyed. After I could cry no more, I just sat there thinking and dreaming, watching my life pass before me.

My hometown, Kozowa, was in Poland (now western Ukraine), the area known as Galicia. It was built among meadows and fields of corn and wheat that stretched for miles. In my mind it came to life in front of my eyes like an oasis in the middle of a desert. I could see the centre of town where there was a marketplace with a round building containing three stores and two groceries. Around the marketplace, streets branched out in all directions. I used to love to run down the hill from the marketplace to my home. At the top of the hill was the drugstore, and as I ran down I would pass a fence, then the pump where we got water, and then our neighbour’s house before getting to our home. After turning the corner and walking up a few steps, I would reach our big, brown front door.

I loved living in Kozowa. The summers were beautiful, not too hot or humid, and the air was always clean, making it a pleasure to take a deep breath. I used to go for long walks in the fields to pick wild flowers or just to get a little sun on my face. On a nice sunny afternoon in July or August, I would dress in a dirndl and sandals, put a ribbon in my hair and walk down to the train station with one of my girlfriends. It was a beautiful walk. We would take a short cut through the schoolyard and then through a garden that looked almost like a park. The garden was private property but had a path that led to the Koropiec River. The water was so shallow that we could even walk across it. The riverbed was uneven and the water ran swiftly downstream, like a miniature waterfall. Over that waterfall was a little bridge. Well, that’s what we called it, but actually it was just a board lying across our tiny river. We would take our shoes off and walk across the board in our bare feet.

On the other side of the river was another path between gardens – mostly vegetable gardens – where a herd of goats roamed. We often talked to the goats, and sometimes they even followed us. It took maybe an hour to reach the train station. We made sure to get there before three o’clock, when the train arrived. The station was a beautiful structure with an iron fence and a garden in back. We waved to the passengers in the windows of the train, and when the train left we walked home with the thought of coming back in a few days. Somehow I never got tired of that walk. I was always excited to go to the train station again.

When I didn’t have anyone to walk around with, I wouldn’t go very far by myself. I walked only to the river, where I’d sit down to read my book, talk to the goats or just listen to the birds. Sometimes peasant girls came to do their washing at the river. One might think this was hard work but it seemed to me, as I watched them, that they were having a lot of fun. They laughed, giggled and told jokes while beating the wash with a flat stick. I don’t think they would have enjoyed themselves more at a picnic or even in a theatre. The girls had long braids and wore tight vests and long, wide skirts, with one hem of the skirt tucked into the waistband. They were barefoot and carried the wash on their backs or in pails. Walking to the river, they made up part of the beautiful picture.

Despite these idyllic scenes, life in our town was not all that glamorous. Maybe we didn’t know better, or maybe we were just smart enough to make the best of it. For instance, we had no running water, so even taking a bath was quite an ordeal. If you were fortunate enough to have a tub in the house, you had to bring water from the pump, heat it in a big basin on the stove, and pour it into the tub.

When you were done, you had to pour the water out again. This is why many townsfolk went to the public bathhouse to take a bath or even a steam bath instead. I don’t know exactly how the steam was made – an old man, Ludz, attended to that. When the steam was ready, another old man, Mikola, went around the streets banging two scythes together to let people know it was time to go to the steam bath. This happened only once a week, on Fridays, when everybody had to get ready for the Sabbath. In the afternoon, all the men left their work or place of business to bathe. The women went later, when Sabbath preparations were done.

Every Friday morning my aunt, who lived around the corner from us, baked cheese buns. They were the best cheese buns in the whole world, and she baked enough for a whole week. My mother, Malka Esther’s, specialty was cinnamon buns. By noon on Friday, the buns were ready – first my mother gave me some cinnamon buns, then I went to Auntie for some cheese buns, and then I took them all to my grandmother’s house. And what a lady she was! My grandmother was very neat and always wore a long skirt, high-laced shoes and a vest.

She had vests in every colour, but especially loved to wear bright colours. Once, she bought a long sweater and, after trying it on, decided it was too dark for her, so she gave it to my auntie and bought a red one for herself. My grandmother’s head was always covered with a clean, starched kerchief. She used to say that she wished she lived in a town where there was no mud so that her shoes could always stay clean. In our town the roads and the side streets were not paved, so after it rained everything turned to mud. We had to wear galoshes or high boots.

[…]

There were so many types of people in Kozowa that I could write a whole book just trying to describe them. And nobody was called by his or her real name; everybody had a nickname. For instance, next door to us lived the shoychet, the ritual slaughterer. His name was Benzion, so his wife was called Benzinachy. What a character she was! She was a religious woman who covered her shaved head with a kerchief, as other religious women in the town did. Yet, somehow that poor woman always looked helpless. She was large, with an apron always tied around her waist, and her face was always dirty.

For as long as I’d known her she had only one front tooth, and she was constantly chewing because it took her such a long time to chew her food. Benzinachy was a good woman who wouldn’t hurt a soul. Many of her children had died young of various diseases, and she was left with only a boy and a girl. She and her husband also adopted a boy named Gedalieh. I remember once when I visited her, she sent Gedalieh down to the cellar to bring her potatoes and said to him,“Gedalieh, keep talking to me the whole time that you are in the cellar.”

When I asked her why he had to do that, she told me that she had preserves and jams in the cellar, and if he was talking she would know that he was not eating up the goodies!

[…]

All the people in town were like one big family. The ones that were a little better off gave meals and clothing to the less fortunate ones. Despite everything, we helped one another in times of need.

*Si vous êtes enseignant au Canada, vous pouvez commander gratuitement les ressources ici.

À propos de l’autrice

Bronia Beker, née Rohatiner (1920–2015) a vu le jour à Kozowa (Pologne, aujourd’hui en Ukraine). Après avoir épousé Joseph en 1945, Bronia et son mari ont immigré au Canada en 1948, où ils ont élevé leurs deux filles, Marylin et Jeanne.

À propos de l’auteur

Joseph Beker (1913–1988) est né à Kozowa (Pologne, aujourd’hui en Ukraine). En 1948, Joseph et sa femme Bronia ont immigré au Canada où ils ont refait leur vie et élevé leurs deux filles, Marylin et Jeanne.

When Josio came into my room he was stunned. I will never forget the look on his face — he could not believe that I was alive. I couldn’t understand it myself. I believe it was fate.