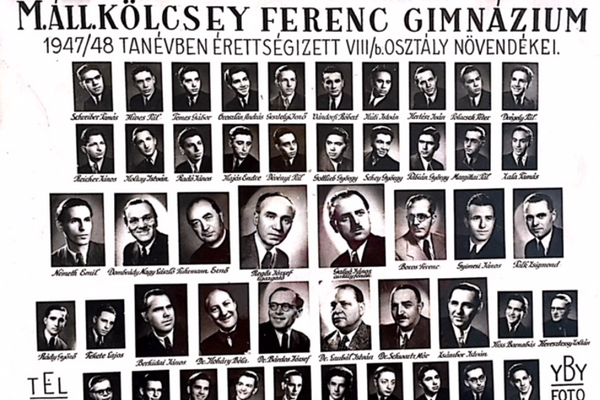

Steve Kuti

Born: Budapest, Hungary, 1930

Wartime experience: Forced labour; ghetto

Writing Partner: Miriam Blumstock Cohn

Steve Kuti was born in Budapest, Hungary, in 1930. In 1944, during the German occupation of Hungary, his family was forced to move to a designated Jewish house in Budapest. Steve worked in a forced labour detail, where his near-fluent German helped him on several occasions.

He was also a top soccer player, which gained him privileges. In the fall of 1944, under the Arrow Cross regime, Steve and his mother were sent to live in the international ghetto, in a house under the protection of the Swiss authority. Steve, his parents and his brother all survived the war. After the war, he lived with his family in Hungary under Communist rule until escaping to Austria in 1956, after the Hungarian Revolution. Steve left Europe and arrived in Saint John, New Brunswick, in April 1957, and then travelled by train to Montreal. He worked at a restaurant and played soccer for the Montreal Maccabi team from 1957 until 1960. From the 1960s until he retired in 2016, Steve worked as a taxi driver, first in Montreal and then in Toronto, where he moved in 1965. Steve Kuti passed away in 2023.

A Comfortable Childhood in Hungary

I had a fantastic childhood. I lived in Budapest, Hungary, on the Pest side of the city, in the thirteenth district, the working-class district. We lived there because my father always said that the rich man doesn’t live in his own house or apartment; he has a house for rent. So, we did. It was also his idea that the owner of a business should live very close to his business. My parents employed between sixty and eighty workers at their factory in this working-class district.

In 1933, my father changed our name from Krausz to Kuti to make it sound more Hungarian. He could already see what was coming and he didn’t want to stand out as a Jew. He must have been one of the earliest to change his name.

I was born on Kartács utca, but when I was three or so we moved to a so-called villa on Palota utca, which we rented. I don’t know how many acres the villa had, but it was full of big trees and had a swimming pool. By the end of our occupancy, there were no more trees because the owner needed money, so he cut down all the trees to sell the wood.

I was a fat little boy around the age of five or six, and my nickname was Szalonna, which means bacon. I had a lot of friends and I was accepted in that proletarian neighbourhood where I grew up, even though I was one of maybe two or three Jewish kids. The other children accepted me because I fought to prove that I was an equal. They would ask for your name and then for your religion. I would say, “I am as Hungarian as you are!” I explained that there was no difference between us. Also, I was a good soccer player.

As I said, we were quite well off. We always had a live-in maid, and I had a Kinderfrau, nanny, whom I called Fräulein. Actually I had a lot of Fräuleins, up to the age of ten. My mother wanted me to have a proper education. As a result, I had piano lessons twice a week and had to practise every day for an hour. I also had to learn to speak another language. I learned to speak German from the Fräuleins that my mother employed.

Steve and his father, William (Vilmos). Hungary, 1935.

Steve and his mother, Margit, outside a Hungarian German private school, circa 1936.

I spoke to Eichmann on three occasions…. He said, “Tell anybody if they arrest you, I will shoot him to death.”

Speaking to Eichmann

In 1940, my family started to notice the worsening anti-Jewish laws in Hungary. Hungarian officials took everything we had. They came into my father’s factory and told him to leave the premises. He went to take his coat, but they told him to leave that too and get out. After the factory was taken, my parents still worked at the factory, but it was owned by a Strohmann, a “strawman” or ghost owner. The business was under an “Aryan” name, and my parents had to pay a gentile an amount of money for use of his name even though he never had anything to do with the business. It lasted maybe six or eight months and it wasn’t so successful. We somehow managed to live with no income.

On March 19, 1944, I was playing soccer in a very famous stadium in Újpest, in the fourth district of Budapest. The head of the soccer organization was also the head of the field. He had allowed us to go in and change in the dressing room but he didn’t give us anything, so when the first game started at 7:00 a.m. there was nothing much going on. By halftime, we realized that German soldiers were watching us. There was a wall above the stadium, and German tanks were lined up beside the wall and the Germans — well, they watched us play soccer. They were soccer fans. They never said a word. They didn’t ask us anything. We finished the first game and the second game and after that, everybody went home. Everybody saw that the Germans had occupied Hungary, including Budapest. You didn’t have to be told. We could see it with our own eyes.

The deportations started after the German occupation, in May 1944. They deported Jews from everywhere in Hungary except Budapest. If you lived outside of Budapest, then you were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, but if you lived inside the city, you were not deported. The deportations of the Hungarian Jews were finished by July 1944; later, the Jews of Budapest were to be deported. They survived only because Hungary’s leader at the time, Miklós Horthy, delayed the mass deportations in the city, although there were deportations later in the year, in the form of death marches.

***

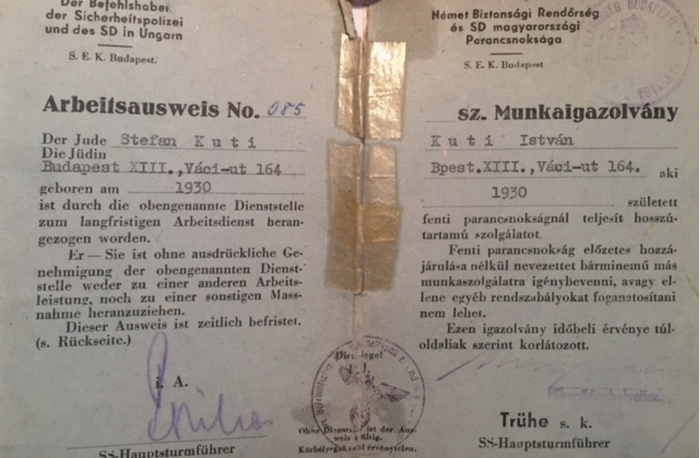

I had been transferred to labour in the Buda Hills, near where Adolf Eichmann had acquired a villa. I spoke to Eichmann on three occasions. I knew who Eichmann was. He spoke to me because he knew that I spoke German almost fluently. Some of the other workers spoke German, but not as well as I did.

The first occasion that we spoke, Eichmann called me over, gave me a bottle and said, “Go down and get me some wine. Here is the money.”

I said to him, “Today I don’t have the star. I don’t have papers. What happens if they arrest me?”

He said, “Tell anybody if they arrest you, I will shoot them to death.”

I went down the hill to the tavern. I had dark curly hair, which made it obvious that I was Jewish. As soon as I walked in, a drunk said, “Here comes the Jew for wine.”

The proprietor said, “Well, I am sorry, but according to the rules I cannot serve you.”

I pointed to the villa and said, “Do you know who lives up there?”

The owner said, “I know.” I said, “He sent me down here.” Right away he gave me the wine.

The second occasion was when Eichmann was at the bunker we were building. He wasn’t there often, but when he was there, he always told us how much more work we had to do. One Saturday, we were very lucky because the area we were working on wasn’t hard to dig; the portion of the ground was more like sand, and so we made the quota quite fast, I think by around one o’clock in the afternoon. When we were done, the other guys told me, “You speak the best German. Go to him and tell him that we made the quota. Maybe he will let us go home.”

I went to Eichmann and said, “Herr Obersturmbannführer, wir haben die Quote gemacht.” (We made the quota.) “Come down, take a look.” He came down, took a look and said, “Go home!”

The third time I had occasion to speak to Eichmann, I went to him and said, “Obersturmbannführer, I want to leave early.”

He said, “Where do you want to go?”

I said, “My parents and I want to convert to Christianity.”

Eichmann said, “Ach, it won’t help you at all.”

My mother and I never wanted to convert; only my father did. It was his idea; he thought that it would help us to survive. After speaking to Eichmann I left the villa and went to the convent. My mother and father were there waiting for me and I said to my father, “I don’t want to convert.” He said, “Why not?”

I said, “Because Eichmann let me leave early but he told me that it won’t help me at all. I won’t convert. You can stay if you want to.” My mother and I left. Two minutes later we looked back and my father was behind us. We never converted!

***

At that time, we had a curfew and were only allowed to be on the street between 11:00 a.m. and 3:00 p.m. But at ten o’clock at night, on a busy street corner, I stood with my star on my clothes, waiting for the streetcar. A goddamn Hungarian saw me and went to a German soldier and said, “That Jew has no right to be on the street.” The German soldier — a very good-looking guy, I never forgot his face — came to me and asked, “Do you speak German?”

When I said yes, he said, “Do you know you cannot be on the street?”

I showed him my papers, which had Eichmann’s name and signature, and he saluted me, that German soldier! By now there were fifty Hungarians standing around watching. They looked and wondered, who the hell can this young Jew be who the German officer saluted?

***

There were two ghettos in Budapest, the gated ghetto and the international ghetto. We were in the international ghetto in a house that was under Swiss protection. The Swiss vice-consul Carl Lutz did a lot for the Jews. He, like Raoul Wallenberg and Giorgio Perlasca, gave Jews false identity papers, saying that they were under the Swiss authority.

Although we were supposed to be “protected” in the international ghetto, the Arrow Cross did not accept this. They came in and took me away, but my mother was not taken. She had put a scarf around her head so she looked older, but I was taken along with many others. It was a Tuesday, I think December 5, and we were taken to a gathering place at Teleki tér 3. This was the men’s holding place; there was one for women at Teleki tér 11. There was a nearby train station, Józsefvárosi pályaudvar, and when the Arrow Cross filled up the house, they took the gathered people and put them in wagons and took them away. I wasn’t taken on the wagon. Because I was fourteen, they left me there. Somehow, someway, they made an exception. I tell you, it’s all luck!

Margit and William Kuti in front of their potato processing plant. Hungary, 1941.

Steve’s work paper in German and Hungarian. Budapest, 1944.

Escaping Communism

Then luckily on January 16, God bless them, the Soviet army came in and liberated us. One soldier, big like hell, ripped off my yellow star. I went to help them push the cannon and he gave me a bicycle. Everything was stolen, all the stores were empty, so he gave me a bicycle. I had that bicycle until 1956. When my parents sold it, they said it was the only good money they got from me after I left!

The ghetto was liberated two days later. There was house-to-house combat, with the Germans and the Hungarians trying not to let Budapest fall into Soviet hands. On January 18, the Pest side was freed but the Buda side, on the other side of the Danube, was not freed until February 13, twenty-six days later.

We went back to our original apartment, which had four rooms with two bathrooms and a small room for the maid. When we got back to the apartment, there were already three other people living there. Two of them lived in one room. We had the middle two rooms and the third person was living in the room for the maid. My parents lived the rest of their lives in that shared apartment.

I was very lucky that my mother and I, my father, my brother and my cousin, with whom I was very close, all survived. I lost a lot of aunts and uncles and a few first cousins from my father’s side. On my mother’s side, there were only three descendants and all three survived.

My parents never got their factory back. We went back to Újpest, where there was a market. My parents had a stand at the market where they sold potatoes and onions. My father did a lot of wholesale business. In Grade 7 I used to help my father. During the summer holidays when there was no school, we would rent a truck and drive almost to the Slovakian border, where we’d buy potatoes from the peasants there and bring them back to Újpest to sell to the small business owners who sold only retail.

***

Living under communism was difficult for us. I restarted soccer when I went into the army in 1950. In 1951, I was charged with the crime of not getting out of bed after injuring myself playing soccer and was put in jail for five months. The officer asked me to get out of bed, but I told him, “As long as there are people like you in the Hungarian army, it’s worth nothing!” They wanted to make an example of me. My mother was so relieved when they said only five months in jail; she had thought I would get two or three years.

We had to work while we were in jail, but we were paid for the work. We loaded supplies and cleared nationalized farmland. First, I was sent to the city of Kecskemét. We were told we were building a military airport for the Soviets. We never did see the airport. They brought in trainloads full of supplies — cement and all kinds of things — needed to build an airport. We had to unload the trains and load the supplies onto a truck that would take them to where the airport was being built. November 7 is the anniversary of the big revolution in 1917, and we were told that the airport was supposed to be finished for that date. It wasn’t ready. Two or three days later, five of us were charged with sabotage because the airport wasn’t ready — Baron Lepotsky, Baranya, Bateri, me and a fifth guy whose name I can’t remember. We were “class strangers,” so they wanted to make an example of us. Only two classes were accepted by the communist system: the working class and the peasant class. Anybody who did not belong to either of these classes was classified as a class stranger.

One of the heads of the investigation asked the five of us, “Does anyone have any questions?”

Nobody said a word. Then I said, “I have a question, sir. Please tell me where the airport is because I want to know what I sabotaged.”

Right away, the head said, “Go out!” Two minutes later they came out and told us the charges had been dropped. No more charges!

I was never afraid. I knew the communists wouldn’t kill me. With the Germans there was a possibility that a bad German could kill me without a reason, but I was not afraid in the communist system. All I said was I would like to know where the airport is and what I sabotaged. The guy was stunned!

We went right back to work and I never knew what happened to that airport. If it exists or it doesn’t exist, I have no idea!

***

A few of us were studying the situation in Hungary in 1956. People had had enough of the Soviet occupation, the terror and the oppression. I decided I would go to Canada. My mother had an old acquaintance in Montreal who sent me a sponsorship. All I knew about Canada was that Montreal was the second biggest city and was a French-speaking city.

After fleeing from Hungary to Austria at the end of 1956, I arrived in Montreal on Tuesday, May 7, 1957. When I got off the train at the Montreal Central Station, around six o’clock in the morning, there was a guy who waited for all of the immigrants. He told me that they couldn’t find the people who had sponsored me. They had sponsored me under a false name because they didn’t want to have any responsibility for me. When the guy asked me if I had anywhere to go, I said yes. I knew the address of my fiancée, who became my first wife. All I knew in English was “fiancé of Agi,” and then my life in Canada started! We got married on June 18, 1957.

The day after I arrived in Montreal, I went to the immigration office and was told that if I learned English, I would get a job. I went back the next day. They asked, “Does anyone speak German?” I said yes and was sent to a restaurant on Sainte-Catherine Street, where I got a job right away as a dishwasher from 3:00 in the afternoon until 2:00 in the morning. It paid thirty-five dollars plus food. That’s how I started. The Maccabi soccer team took me out of the dishwashing job after one and a half weeks. There was a private detective, Mr. Green, who was a supporter of the Montreal Maccabi team. He said, “I’m from Maccabi, and you are going to play for us.” Someone had told him that I was coming. I played soccer for the Montreal Maccabi from 1957 until 1960.

I started to drive a cab in 1959 in Montreal. In 1961, I bought my own cab. I spoke German, Italian, English and Hungarian but could never learn French. I left Montreal for Toronto in 1965. I became a taxi driver and a taxi owner.

In 1990, Co-op Cabs took me into the office. I became the toast of the taxi business one or two years later. Taxi drivers got a lot of parking tickets, but they didn’t have to pay if the car was not in their name. If the car was in the owner’s name, it was the owner’s responsibility. So, when Co-op hired me they asked me to find a loophole with the parking tickets. On the back of the yellow tickets, I found it said “contrary to Toronto bylaw …” or “contrary to Metro bylaw …” I went into Old City Hall and asked for the Toronto bylaw book. They gave it to me; I pretended to look something up and then gave it back. Three days later, I went back and asked for the Metro bylaw book. The woman there said there is no such thing as a Metro bylaw book!

I went back to the office and separated out all the tickets that had “contrary to Metro bylaw” on the back. They weren’t valid! The taxi business praised me. Even the young prosecutor liked me very much; he said, “Mr. Steve, you are a genius!”

Five months later, I went in and he told me that I wasn’t a genius anymore. The law had been amended. And like that, my genius was gone!

I stayed at Co-op Cabs until July 4, 2016. They kept me for so many years; they created a job for me. If they had something official, like needing someone to talk to the Premier of Ontario, they sent me. I took the bank deposits every day. They gave me $460 every two weeks. I lived like a king! I still live like a king!