Sophie Pollack

Born: Słotwiny, Poland, 1924

Wartime experience: False identity/hiding, ghetto, forced labour

Writing Partner: Yvonne Chmielewski

Sophie Pollack (née Sala Ell) was born in the village of Słotwiny, Poland, in 1924. In 1932, she and her six siblings and parents moved to Lodz, Poland. After the German occupation of Poland in September 1939, Sophie and a cousin left Lodz for the small city of Skierniewice to stay with relatives.

Sophie found work on farms until an order came into effect for Jews to be evacuated from the area and sent to Warsaw. Sophie, instead, left for the town of Koluszki, where her great-uncle lived, and continued to work on farms, passing as a gentile, even after the ghetto in Koluszki was established and then liquidated. She eventually ended up in the ghetto in Ujazd and coincidentally escaped one day before its liquidation. In January 1943, Sophie, in order to join two of her sisters, took on the Polish gentile identity of a farmer’s daughter who was to be sent to work in Germany. Sophie worked in a factory in Krefeld, Germany, as an interpreter, close to where her sisters worked. After the war, she reunited with her sisters, and they lived in a displaced persons camp near Eschwege, Germany, until Sophie and one of her sisters came to Canada as domestic workers in 1949. In 1950, Sophie met her husband, Norbert, at an English class, and they married later that year. Sophie raised a family, enjoyed cross-country skiing and sang in choirs. Sophie Pollack passed away in 2020.

A Large Family

My village, Słotwiny, stretched from a road beside the railway into clusters of houses, farms and meadows. The buildings closest to the railway station and the road, the business section, consisted of a barbershop and three stores selling a variety of merchandise and alcohol. Each of the buildings had several flats and my family occupied one of them. It was composed of two fairly large rooms. There was no running water and no electricity. We used an outhouse year-round, even in the bitter cold of winter. One of the rooms was heated by a coal-burning stove and served as a kitchen and had some beds in it. The larger room was a combination bedroom, dining room and playroom. It was heated by coal in a tiled heating oven. There were no modern conveniences, and funds were limited. Father worked in the city and only came home on weekends.

How did our mother manage to keep seven children between the ages of one to twelve fed, clean and healthy? The older girls cared for the younger ones, and we actually managed to enjoy ourselves. My oldest sister Janet (Zlata), eleven years older than my youngest brother, had to take care of me when we went to school. She was very bossy, and I was scared when she would get mad at me.

During my early childhood, though, my sisters went off to school, and I was left on my own. My mother was busy looking after my two younger brothers, Shajo Meyer and Schymek. I remember around the age of four feeling frustrated and angry because I was too young to participate in activities with my sisters and too old to have the attention that the babies received. I spent time walking through the meadows around our tiny village, picking wildflowers. This is when I developed my love of nature. Relying on myself shaped my character and helped me during the war.

There was no doctor within reach of our village, but our mother kept us healthy. She knew which plants, herbs, flowers and even weeds were used for each ailment. She did not have any formal education but did have common sense and strength.

I remember the forest being a source of magical experiences whenever my older sisters let me go along with them. Each season offered us different gifts. There was always an abundance of beautiful wildflowers. In spring and early summer, we picked wild strawberries, blueberries and a variety of other berries. There were many types of mushrooms, and we knew which ones were safe to eat. Mother was pleased with the contributions we made to our meals.

I had two years of schooling in Koluszki, a small town about twenty kilometres east of Lodz. Koluszki was important because it was a major railway point in central Poland, connecting trains that went from Warsaw to Lodz and Częstochowa. About half the town of Koluszki worked for the railway in some capacity, and the town developed around the railway and bus stations.

I was the only Jewish child in my class. Classes were held from 8:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. and again from 1:00 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. for a different group of students. A priest came every day to teach prayers and hymns. My parents were very religious so when he came in, I had to leave the room and sit by myself in the corridor. I remember asking Janet, “Do you leave the classroom when the preacher comes to teach religion? I feel so lonely sitting alone in the hallway for an hour.”

“Of course,” she said. “The preacher makes the children cross themselves and say prayers. It is a sin for Jewish people to do those things. Sometimes he tells the class that Jews killed Jesus and the kids act mean to us.”

“I know. That’s why nobody plays with me. I don’t like going to school.”

“Stasia is not Jewish and she is my best friend. You might still make some friends. You are only in Grade 1. Anyway, Father is trying to find a place for us to live in Lodz. There are many Jewish children there and we have separate schools. No priest there!”

Overall, I don’t remember having major problems being Jewish in that town. My sisters rarely played with the gentile children, but my sister Bronia, like my sister Janet, had one very good gentile friend. My mother was friends with her mother. Everyone was poor, and we helped each other. No matter how poor we were, we always had bread. But milk was only for babies or young children.

My mother was more religious than my father and was very strict. In spite of our poverty, on Fridays our table was set with a nice, white tablecloth, and we ate chicken or gefilte fish. We didn’t get much but it was always a festive dinner. Mother lit the candles. Passover was a big event as well.

Our whole family moved to Lodz in 1932. We lived in a huge building there, which might have been a factory at one time; it was in a very poor neighbourhood and many Jewish and non-Jewish families lived there. We had one huge room that we divided. This was a common thing for families to do.

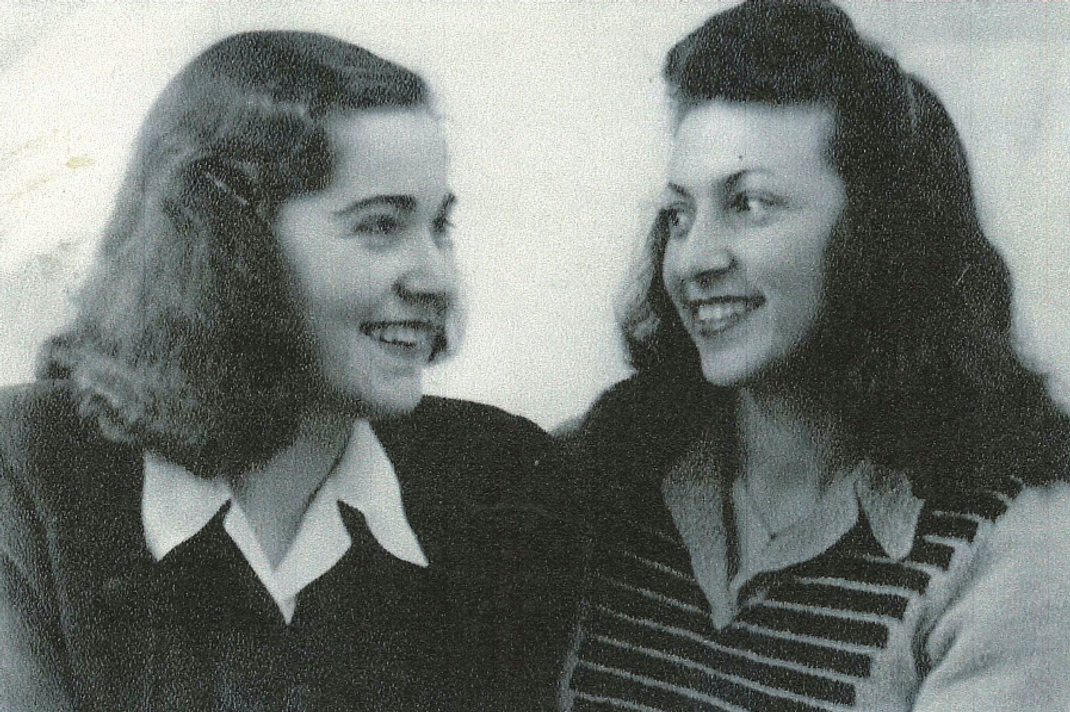

I had always fought with my sisters often because they wouldn’t take me along with their friends or play with me. When Janet and her friend Stasia would get busy talking together, I was ignored. After we moved to Lodz, things eventually changed, and my sister who was two years older than me, Chawa, became my best friend. I had fought with Chawa the most, but after we moved to Lodz, she said that we shouldn’t be fighting, that we could be friends. That meant so much to me, and I will never forget her words. I leaned on her, and she was there for me all the time. In Lodz, I went to school and was a very good student, which gave me more confidence. Having Chawa as my best friend helped a lot too. My other sisters, Bronia and Elka, were also very good to me.

***

I lived in Lodz from 1932 until 1939. When Hitler came to power in 1933, there were many ethnic Germans in Poland, especially in Lodz. Whenever he made a speech, which was often, they would turn their radios up, and we could not avoid hearing him. These speeches were so full of hate against the Jews — every second word... it was terrible. Even at only ten years old, I felt the fear that everyone else was feeling. Hitler would say that all Germans had the same duties and obligations in enforcing the rules. There was marching in the streets. We heard about people being beaten up by gangs. That was normal life. This was a strictly Catholic country of poor working peasants. The church was their source of information. It was a terrifying environment to be growing up in, but then, we never felt that secure in Poland. As Jewish people, we had never felt equal.

But there was no time to mourn or worry; I still had to fight to survive.

Life in the Villages

In November 1939, with the Nazis occupying the city, my cousin Ida and I left Lodz and went to Skierniewice. Ida was an only child and was raised primarily by her grandparents. Obtaining food was difficult; my cousin looked stereotypically Jewish, so I was the one who lined up for food. The Germans were calling all young, able people to work. I wasn’t officially listed as living in Skierniewice, so I would report to work in place of Ida. She was very skilled with her hands and supported herself and her grandfather with knitting. People would bring her old sweaters, and she would unravel the wool and knit new items. When I lived with her, she taught me how to knit, and the two of us sat through the winter of 1939–1940 knitting and singing songs. She was very religious and brilliant in every way. My grandparents had sent her to a religious Jewish school. She also had a public school education in Polish but had a Yiddish accent because she mostly spoke Yiddish with her grandparents.

My mother walked from Lodz to Skierniewice to see me for the last time in the spring of 1940, just before the Lodz ghetto was closed. This was quite a distance. Her father-in-law, our grandfather, did not know that Father had died. We never told Grandfather that his only living son was now dead, but I think he knew that something was wrong.

Many young people had left Lodz because it was now part of Germany. My cousin’s grandparents had relatives in Skierniewice, and my cousin knew many of them. We all needed to work, so during the summers we asked the farmers in the area for work. They were happy to have us even though we did not have any experience. We worked for food. I started just taking the cows to pasture and then eventually milking them. I was so scared of milking the cows because they kept hitting me with their tails as they chased the flies away, but as I became more confident, my duties increased. I fed the chickens and then began doing more work in the field. This was quite an education and gave me a good start in learning how to help farmers. I was lucky because I enjoyed some of that work — being outside, in the fields, working with the soil. It was a beautiful summer. The following year I was active in a different village because of my work experience.

In February 1941 there was an announcement that all the Jewish people from Skierniewice had to leave and go to the Warsaw ghetto. Skierniewice had to be free of Jews, judenrein, by the spring of 1941.

In the winter of 1940–1941, my sister Bronia had come to Skierniewice to stay with us. This was just as the Jews in the town were being evacuated. I made two or three trips to Koluszki on my own, taking some belongings there. On the last trip I went with Bronia. Ida and her grandfather must have gotten a ride with someone on a horse-drawn wagon.

I bought a train ticket and was waiting with Bronia for the train to arrive. We were going through to the collector, a Polish man, and were stopped. When I was on my own there was no problem. But this was the last day of the evacuation, two of us together, and he must have gotten suspicious. As we tried to get through the wicket, he told us to wait. He obviously knew we were Jewish. I was standing with Bronia, and he was busy with other people. Bronia said quietly, “I’m going. I’m not waiting.” I moved to shield her, and he noticed that she was gone. He was angry but still busy collecting tickets, so I left as well. This was a Polish man, not a German. Why did he have to be so...? I left and he must have sent a German soldier to chase after me. I didn’t run; I just kept walking with the rest of the crowd, trying to blend in. Finally, the soldier started shouting, “Jude, Jude!” (Jew, Jew!)

I ignored him but he caught up to me. A group of people approached and stayed near me. He asked if I was Jewish. A young man stepped forward and said, “No, she is with me.” I managed to escape, but that was such a close call. Once you are caught, you could be sent to a concentration camp and interrogated. We met so many wonderful Polish people, but this police officer was eager to cooperate with the Germans.

After that incident, we couldn’t take the train anymore but managed, like my cousin, to get a ride with someone on a horse-drawn wagon. We made it to Koluszki and stayed with one of my great-uncles. Koluszki was close to the new border between the part of Poland annexed by Germany and occupied Poland. Many people would cross the border to smuggle cheap food from the German part to the occupied territory. My sisters knew some women who did this, and for some reason they decided I should go with them. They set me up with a couple of people who were planning to cross the border.

I crossed and got bread, but some soldiers stopped us. The other women were more experienced than I was in these situations. I tried to hide but one of the soldiers caught me. I was horrified and had no idea what to do. He started to walk me toward the woods, thinking that he could rape me or thinking that I would be willing. I was still a virgin and had absolutely no idea what he wanted. I was begging him to let me go and was crying. He realized that he was dealing with a child. He let me go and actually showed me the way to Koluszki. Of course, he didn’t know that I was Jewish. I was so naive, which I think helped because that soldier really felt sorry for me. This was an experience I could never forget.

The ghetto had not been formed yet. However, it had already become too much of a risk for my cousin to continue with her knitting because she was easily identified as a Jew. However, she had taught me, and I contacted some people who had known my parents. Many of the people who lived in Koluszki were employed by the railway and could afford to buy items like my knitting. During the early winter of 1941, I knitted for some of these people. In the early spring, because of my experience, I was able to work for some farmers.

Many of the Polish people remembered my parents and were helpful to us. The ghetto in Koluszki was opened in April 1941, and Jewish residents of Koluszki were crowded into it along with Jews from nearby Tomaszów Mazowiecki and other villages. The borders of the ghetto were not strictly guarded, but any Jews caught outside were shot. Some of the Jewish children who went begging outside the ghetto were murdered.

It was not official and we were not supposed to talk about it, but we knew that Jews were being transported to concentration camps at night. We heard the rumours, which were too horrible to believe. The trains passed by, and the employees of the railway who worked outside could hear people crying and banging and screaming. These people were packed together like cattle.

Since the ghetto was not strictly guarded, I left many times. I still had contacts in the village of Słotwiny where I had grown up and spent most of my time there. The people were very good to me and recommended places where I could go and knit. In the summer I worked on a small farm. I could do all of this because I did not look Jewish. I was being fed properly because I had contact with these people in the village. I had a round face and looked healthy. Most of the people in the ghetto were marked through hunger. They were thin and starved. The ability to get food was not as difficult as it was in the Warsaw and Lodz ghettos, but it was hard enough, since we had to buy it on the black market. When I worked on the farms, I would be paid in food, which I brought to my sisters. Janet also left the ghetto and did some selling. I was the only one who had regular work, but it wasn’t enough.

My eldest sister Bronia was married in the ghetto and eventually became pregnant. That was the worst thing that could have happened because it was impossible to feed a baby. Sometimes I was able to bring milk, but she was unable to leave. Sadly, she was not the only one to have a baby. There was a young woman who had a five-year-old child. Her husband was not able to get out of Lodz, but she had managed to escape with the child, alone, and was absolutely helpless. She had no way of providing food and watched her child die of starvation. We couldn’t help her because we had a baby, too. There were many families who experienced this tragedy.

Passing from Ghetto to Factory

In early January 1943, I was living in the Ujazd ghetto when a middle-aged man there told me he had some money in Koluszki but didn’t dare go there to get it, since Jewish people were not allowed to take the train — or even permitted to leave the ghetto. When he asked me if I would get the money for him, I agreed. As I was leaving, one Polish police officer stopped me. He had known my father but, even so, persisted in trying to prevent me from leaving. I begged him to let me go and finally had to give him money.

I managed to get to Koluszki and obtained the money from the man’s family, but I missed the return train. I walked to the next village, to one of the families where I used to stay, and pleaded with them to keep me for the night. They were so scared because the Germans were looking for me. Someone in the village must have informed against me. I told them that I would sleep in the stable and if I were found, I would say that the family didn’t know, so they let me stay.

Early in the morning, I went to the station and took the train back to Ujazd. When I arrived, I went to visit a woman in the town who had been good to me. She looked at me as if I were a ghost and said, “What are you doing here? The ghetto was destroyed last night.” I was delayed just one night! I thought about this coincidence and my luck for many years after. I don’t think anyone would have been able to escape. I walked by that ghetto and saw that the buildings were still smoking from fires that had been set. The ghetto was now just ruins and smoke. But there was no time to mourn or worry; I still had to fight to survive. A young man followed me and said, “I know who you are. If you wait here, I’m going to help you.” He must have seen me leaving the ghetto.

I quickly walked away and hid in the woods and then found the people whose address my sisters had given me. Though I didn’t have many belongings with me, I did have that money, but I didn’t know what to do with it. If I went to Germany, I would have to exchange it.

The girl in that family had not received her summons to go to work in Germany. I stayed with them for a while but was getting nervous, since at that time every household had to provide a list of people who were living there. I decided to contact another family my sisters told me about. They needed me to go to Germany in place of their daughter who had already received her summons. I started using the name Sophie Szmejda. Many of these young girls stopped existing in their villages because their identities were taken over.

Sophie was the only daughter of a farmer. They were very happy to help me and treated me well. They didn’t know that I was Jewish. I had to go to church with them, but I had spent a lot of time with Christians and knew how to cross myself and sing along with their hymns.

The transport sending workers to Germany was to leave later that month, January 1943. Everybody was collected in Częstochowa, the transit point. I was just hoping to be near my sisters again. We travelled on the train for two days and two nights. Many people travelled alone, and I was able to make some friends. When the train finally stopped, I saw the sign for Wuppertal, Germany, which is where my sisters were. I was thrilled to be in the same place as my sisters. They came to see me after I got a message to them. I didn’t stay there but went on to Krefeld, where there was an artificial silk factory that needed workers. The sixty kilometres from Wuppertal and Krefeld could be covered by a streetcar ride, so my sisters and I were able to keep in touch.

The people in the transport with me were mainly uneducated Polish peasants. Nobody spoke German, and when we arrived at the factory, a translator was needed. I had learned German from an engineer back in my hometown while knitting for his young daughter. I volunteered to interpret at the factory in Krefeld and became an interpreter for my group. This was risky because I might have mistakenly used a Yiddish word. I interpreted for a Russian group as well. Being able to speak German meant that I didn’t have a death sentence hanging over my head as I did in Poland. I was legal. I was an equal. I had Polish papers. Ironically, I felt quite liberated once I was in Germany.

When I visited them, my sisters introduced me to a non-Jewish Polish man named Leon, and we fell in love. He knew that I was Jewish and said that if anyone revealed my identity, he would protect and defend me.

I worked in Krefeld with another young Polish woman named Marysa who also acted as an interpreter. She had a high school education, which was uncommon even for non-Jewish people. She was beautiful, intelligent and cultured. She chose me to be her best friend, and we did many things together. We didn’t work in the factories but had other, more privileged jobs, such as distributing meals and cleaning up. We would accompany people to the doctor and act as interpreters.

One day Marysa said, “You know, Zosia (Sophie), I am not a violent person but I could kill any German and any Jew.” My God, this was a cultured girl from Warsaw or Krakow! I thought, You picked a Jew to be your best friend. I generally had good experiences with Polish people, but this one… And comparing Jews with Germans!

After the war ended, I had such satisfaction telling her that I was Jewish. I don’t remember her response but I’m sure she was embarrassed. I thought that maybe this taught her a lesson and perhaps she changed her mind about Jewish people. After all, she liked me as a person — she picked me to be her best friend!