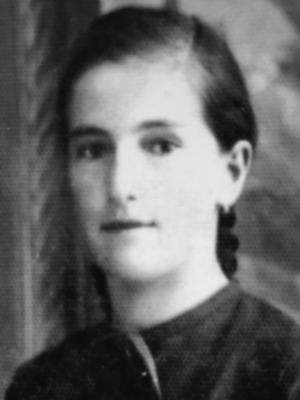

Liza Eshanou

Born: Heleșteni, Romania, 1928

Wartime experience: Survival in Romania

Writing Partner: Judith Levine

Leah (Liza) Eshanou was born in Heleșteni, Romania, in 1928. She survived the war in Romania under the antisemitic rule of the Iron Guard and the Antonescu regime, forced to relocate according to anti-Jewish decrees.

She and her mother survived through luck, never being deported like so many of their Jewish friends and neighbours. Although they experienced constant antisemitism and lived in fear of the authorities and some non-Jewish Romanians, Liza and her mother also survived through the support of other non-Jewish Romanians. Liberated by the Soviets in 1944, Liza eventually fled from Soviet-occupied Romania and then Hungary to displaced persons camps in the American Zone in Austria, where she met and married Sam. She and Sam immigrated to Canada in 1948, where she was joined by other family members who had survived the Holocaust and where she raised a family of her own. Liza Eshanou passed away in 2017.

Lucky to be Protected

I was six years old and wanted to go to school like my siblings. In our school students started Grade 1 at seven years old, but I kept bothering my mother until she took me to the principal, Domnu (Mister) Mitru. I started school a year early, in 1934, and my education ended in 1939 when Ion Antonescu, influenced by Hitler and later allied with him, issued a decree forbidding Jewish children from continuing their schooling. If I had not started early, I would have had only four years of education.

I went to school with my brother Șulim. When Șulim was old enough to start school, my mother paid a woman in the city of Pașcani to take care of him so that he could go to cheder, Jewish school, after regular classes. When my mother went to see him there, she found him unhappy and neglected and brought him home. Șulim lost a grade, and I gained a grade by starting younger, so we were in the same class. I was lucky to have a protector. Șulim was tall and strong, and when the kids picked on us for being Jewish, he defended himself and me. They used to call us Jidani, Jews, in a derogatory way. The proper name for Jews in Romanian is Evrei. They accused us of killing Christ and yelled, “Jidani, du-te la Palestina!” (“Jews, go to Palestine!”)

One time, as I walked home from school, I was attacked and there were about six children on top of me. I thought they would strangle me, but my brother Șulim came running and threw them off me, and we ran the long way home. Nowadays, we hear a lot in the news about bullying and the effect it has on children who are bullied. We were more than just bullied. We were attacked both physically and psychologically, and they made us feel inferior. It is called antisemitism, but children do not know such words. They can only suffer from hatred and humiliation. My heart goes out to those who are bullied.

I would often think about my poor brother Hanoch — when he went to school, he was alone. The other kids picked on him for being Jewish, and there was nobody to protect him. One time they threw stones at him, and one hit the back of his head. He developed a bubble full of pus the size of a golf ball. Bunica, our grandmother, sterilized a knitting needle and lanced the ball of pus, and after it drained, it started to heal. Hanoch played hooky from school a lot after that because he was afraid. I used to help him with his lessons and asked my mother to make him go to school regularly. I was only two years older but I worried about him. I continued to worry about my family for the rest of my life, but not enough about myself. Now I don’t think that it is normal; one must be a little bit selfish in order to survive.

We were more than just bullied. We were attacked both physically and psychologically, and they made us feel inferior. It is called antisemitism.

A New Life

Sam and I got married on August 17, 1948, and soon after that we left Austria. Canada was accepting new immigrants who had trades, with companies that needed skilled workers acting as sponsors.

When Sam was asked where he learned tailoring, he answered that he’d learned in the concentration camp, and he passed the test. We left Ebelsberg a week after we got married, going by train to the port of Bremen in Germany. It was exciting to see the ocean. The ship we boarded was named RMS Samaria. Men and women were accommodated separately in rooms with bunk beds to save as much space as possible. We gathered for meals, and during the day we stayed on deck and enjoyed the view. After supper passengers would sit on the decks and talk.

We arrived at the port of Quebec City and stayed on board ship overnight. In the morning we had breakfast and were taken to the train station. We stopped in Montreal, where all the immigrants were asked if they wanted to stay in Montreal or continue to Toronto. Sam heard the man in front of him saying Toronto, so he said Toronto, too. It made no difference to us, as we didn’t know anybody in either city. When we arrived in Toronto, we were taken to a hall on Spadina Avenue, where we were given lunch. We were told that immigration authorities had found some flats and rooms for us to rent, but there were not enough for all of us. They reserved apartments for the families with children. The rest of us were taken to a building on St. George Street. We were accommodated in a room with bunk beds. We were informed by JIAS (Jewish Immigration Aid Society) that we could borrow four hundred dollars without interest at their office on Beverley Street.

Most of the immigrants spoke Yiddish. We also spoke German because the Germans had been all over Europe during the war and the displaced persons camps were in Germany and Austria. The people who received us spoke Yiddish as well. The needle trade was on Spadina, and most of the tailors were Jewish. As for learning English, we discovered that there are a lot of German words in English. Luckily, I had another advantage: I spoke Romanian, which belongs to the Romance group of languages, and English has absorbed a lot of Latin-based words.

Sam went out for a walk on Spadina the next morning and overheard some men speaking Yiddish. It was lunchtime, and the factory workers were out for a breath of fresh air. When Sam mentioned that he needed a place to live, one man told him about a room for rent in the house where he and his family were renting on Ossington Avenue. It was a comfortable upstairs furnished bedroom at the front of the house. The landlord gave us a hotplate for cooking, but I had no pots. All we had was an oval tin container, about eight inches high, with a handle. It was used by the soldiers to carry food. I cooked in it for quite a while until I bought a pot.

***

In January 1954 we got a letter from my mother asking us to bring her to Canada from Israel, where she had immigrated in 1950 with help from my brother Hanoch. She was very proud of him. Many survivors from Romania came to Israel in 1950. In 1954, she was still dwelling in a tzrif, a small cabin, and Hanoch was digging ditches or doing whatever he could find to support himself and her. It was a young country, and the need was so great. I have to give Sam credit — after losing his parents in the Holocaust, he didn’t mind my mother coming, even though our apartment was very small and there was not enough room for another person. We discussed it and figured out a solution. Gilda had a junior bed and a dresser, which we moved into the living room so we could put a bed for Grandma in Gilda’s room. Mother arrived in Halifax on August 30, 1954. She spent a week with Shelley and her husband in Montreal and then came to be with us.

We were overjoyed to see each other. It was our first meeting since I’d left her to go to Bucharest in 1945. She was thrilled to see her first grandchild, and we talked a lot. She told us about Hanoch and Israel, and also about what had happened to her in 1950 when she was supposed to board a ship in the Romanian port of Constanța for Israel. During and after the war she had sold all her valuable possessions to buy food, but there was one thing she kept no matter what: a silver link belt with her grandmother’s name, Rachel, engraved on the buckle. When they checked her belongings, they found the belt and strongly suggested she “donate” it to Romania. She pleaded that she was an old woman, and it was her only valuable possession, and she might need to sell it to buy some food later. The officer listened to her and responded that he was not sure that there was enough room for her on board ship. At that point she said, “I will donate, I will donate,” and she gave the belt to the officer and boarded the ship.

After my mother arrived, relatives began to visit us. First my brother Șulim came. He and my mother hadn’t seen each other since 1945. After Șulim left, my mother’s brother Jack came with his wife, Martha, from New York. The brother and sister hadn’t seen each other since World War I. It was a very emotional reunion.

Liza on the RMS Samaria, travelling to Canada. 1948.

Liza (right) with her mother, Clara (centre), and her sister, Shelley (left). In the background (left) are Shelley’s children, Stephen and David, and Liza’s daughter, Gilda. Gananoque, Ontario, 1962.