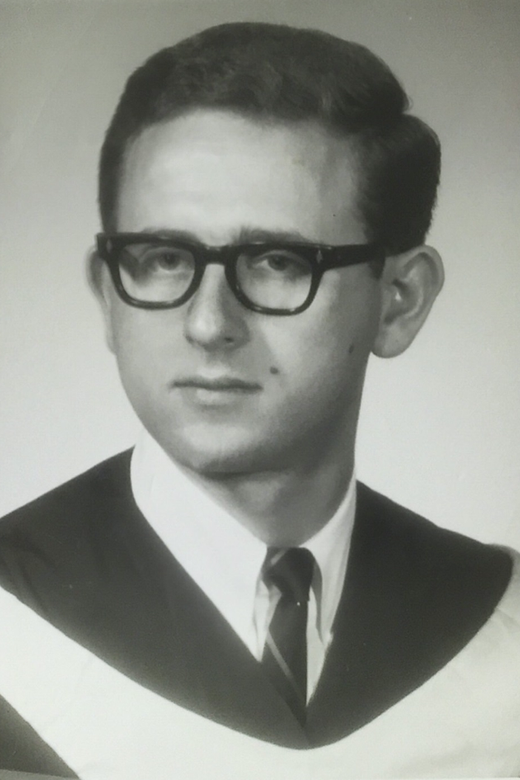

Joe Gottdenker

Born: Sandomierz, Poland, 1942

Wartime experience: hiding/false identity

Writing Partner: Elina Fish

Joe Gottdenker was born in Sandomierz, Poland, in the summer of 1942. Shortly after his birth, his mother was forced to give him up to a Polish family, the Ziołos, and she joined the underground partisans.

Joe lived with the Ziołos on their family farm for over three years, posing as a Catholic relative from out of town. After liberation, Joe was reunited with his father, mother, two uncles and an aunt. Joe and his family immigrated to the United States in 1948 and then to Canada in 1958. In Canada, Joe finished his high school studies and then graduated from the University of Western Ontario and worked as a teacher, entrepreneur and real estate developer. Joe has served as vice-chair of the Canadian Society for Yad Vashem and has volunteered with many other Jewish organizations. He has made it his life’s mission to support Holocaust education and commemoration.

A Young Life in Hiding

My parents knew a Polish family, the Ziołos. Władysław Zioło was a police officer and his wife, Petronela, was a homemaker. They had a ten-year-old son named Tadeusz. My parents made arrangements for me to be born in Sandomierz, about sixty kilometres from Mielec. I’ve been told that my mother gave birth to me in a convent hospital in Sandomierz. Because she had blond hair and blue eyes, she looked “Aryan” and that is why she was able to get false identification papers with the help of the Zioło family. After I was born, my mother and I went to hide on the Ziołos’ family farm. It wasn’t like Anne Frank’s hiding since I didn’t have to hide in a cellar or a closet. I posed as a Catholic relative from out of town who had been abandoned by his family during the war. I don’t know the exact details.

After a few weeks or maybe a couple of months, my mother spotted an antisemitic classmate from university and got nervous. She left the Zioło home and joined the underground partisans. I don’t know about a single day of her life between the time she fled, leaving me with the Zioło family, and the time she came to pick me up after the war. That’s been a very sore point for me; I regret never having asked her about her life during the years of our separation. All I know is that she survived.

At one point, things got a little precarious at the Zioło home, so they wanted to relocate me to their cousin’s home in another town. Shortly before I was to move, the cousin’s neighbours were found to be hiding Jews, and the Jews and the entire Polish family were shot in the front yard of their own home. So I stayed with the Ziołos. When I went back to the location of the Zioło home a number of years ago to do an interview for a film my cousin Daniel was producing about my journey, one of the neighbours who had been in her teenage years during the war said, “I knew they were hiding a Jew there!”

I lived with the Ziołos for a little over three years. I considered them my family. The Ziołos didn’t help for monetary gain; their intentions were totally altruistic. I get emotional about it at times because they risked their lives for me. My parents kept in touch with the Ziołos after the war. They sent them care packages and medicine until they passed away.

I don’t know what I remember or what I was told, but I think I remember Petronela going out into the barn and milking the cows. I’d sit there watching her, and she would playfully direct a spray of milk into my face. I can still taste the warm sweet milk coming right from the cow. Then a cat would come over and lick my face to get the rest of the milk. I was somewhat malnourished. All I ate during the war was potatoes, and I suffered from rickets. The first time I was given an orange, I tried to bounce it!

I don’t know how my parents knew the Zioło family prior to the war. I don’t even think their son knew I was Jewish. He later immigrated to Chicago with his family. I still keep in touch with his daughter, Beata (Betty) Świerć, who lives in Chicago with her family; we maintain a close relationship.

Yad Vashem inducted the Ziołos as Righteous Among the Nations on September 19, 2010. A video clip was made about our story at the time of their induction. Betty and I were interviewed for it and it’s available on the Yad Vashem website. When Betty and I were in Ottawa for a Yom Hashoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, ceremony, a reporter for an Ottawa newspaper asked Betty what made her grandparents do what they did. She said something along the lines of, “You can’t come up with an answer other than they did it because they were those type of people. They felt like it was the right thing to do.” The Ziołos were very different from most people at the time because they chose not to be bystanders.

Even though I don’t remember those years, they still affected me subconsciously. I had lived for over three years with a woman who I thought was my mother, and then a “stranger” tore me away from her.

Living with Trauma

I attributed all my behavioural issues and rebellion solely to the war. It’s a great excuse, isn’t it? It’s the war; it’s not me! What resulted from the war was a dysfunctional life. I spent over a decade on a psychiatrist’s couch dealing with my issues as a child survivor, as an only child of survivors. The psychiatrist attributed a lot of my issues to my being deserted by my mother at birth. Even though I don’t remember those years, they still affected me subconsciously. I had lived for over three years with a woman who I thought was my mother, and then a “stranger” tore me away from her. I knew nothing about my birth mother when she came back for me. I was Catholic, then I was Jewish. I lived in Germany, then the United States, then Canada. There was a lot of change for me to deal with. The psychiatrist told me that having gone through what I did as a child and living with Holocaust survivors had greatly affected me.

One day, I got a phone call from the psychiatrist’s office advising me that my appointment was cancelled because the doctor had passed away. I attended the shiva, the house of mourning, and called the widow a few weeks later, asking for my file. She told me I could come pick it up if I wanted it. So I went over and had tea with her. She gave me a manila envelope with my file in it. I have never opened it because I’m afraid to see what the psychiatrist wrote about me. Some researchers say that the horrors of war are passed on to children; the trauma is passed on. I have not lived a conventional life because of the aftermath of the war. For this reason, my involvement in Holocaust education is now paramount in my life. I invest a lot of my energy and financial resources into Holocaust education.

Going Back

When I went back to Poland for the first time in 1992, some Polish locals harassed me. I think they were afraid that I was coming back to claim my property or belongings. One of the greatest satisfactions I had was walking down the streets of Krakow on the Jewish holiday of Rosh Hashanah with a tallit bag, a prayer shawl bag, in my hand, thinking, “We’re back. We’re here!”

While I was trying to locate my grandparents’ homes in Mielec, I met an older gentleman on the street. I asked him in Polish if he knew where the Gottdenker house was located. He pointed to an empty field. I got excited, thinking that maybe he knew my family, so I started to rhyme off my uncles’ and my parents’ names. When I got to my father’s name, the Polish man finally remembered my family, so I told him that I was the son of Bendet Gottdenker. He turned as white as the wall he was leaning against. He hadn’t thought any Jews had survived the roundup in 1942, when the majority of the Jews were shot to death and the rest sent to work at the aircraft factory. To the best of his knowledge, no Jew had returned since the war.

The old gentleman took me to my mother’s parents’ home, which was a little house with a thatched roof. Living there were two elderly women who had been squatting there since the war. I brought out a carton of cigarettes and a bottle of Johnnie Walker from my car, and as the three of them smoked and drank, they shared with me what they knew about my family and even drove me to Sandomierz, where I had been born. As I was preparing to leave my maternal grandparents’ home, one of the women went into a room and came out with two sterling silver Shabbat candlesticks. They had saved the candlesticks from the Germans and the Poles. They knew that someday, someone would return for them. They told me that the candlesticks were the only items they had been able to save. I gave them to my aunt Shirley, Uncle David’s wife, and she lit them every Friday night until she passed away in February 2016 at the age of ninety-six. There is a short film called Candles of Kindness on YouTube about these candlesticks.